Philanthropic collaboratives that channel resources from multiple donors to nonprofit organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and other social-change initiatives are on the rise. Based primarily on survey responses between 2022 and 2024 from over 300 such funds, this report paints a robust picture of the current landscape. It suggests how collaborative leaders and donors might grow and strengthen this increasingly important segment of philanthropic giving.

The Bridgespan Group’s research in recent years has highlighted the great potential of funder collaboratives to unlock and deploy more philanthropic resources to advance social change:

- Collaboratives are one of four compelling pathways to increase philanthropic contributions among high-net-worth individuals.

- When executed well, collaboratives can produce significant impact.

- Collaboratives offer substantial benefits for donors looking to engage across issue areas and to give efficiently and effectively.

- The majority of collaboratives have charted a course that differs from traditional philanthropy: they tilt toward equity and justice, field and movement building, and leaders of color.

- Collaboratives have unique opportunities and challenges regarding measurement, evaluation, and learning—with some promising frameworks others can learn from.

- Donors can engage with collaboratives in issue-specific ways, (e.g., in democracy, gender equity, racial equity, or climate) and regional ways (e.g., in India, in Africa, or more broadly across the Global South); to illustrate this, our database of philanthropic collaboratives has grown to over 300 funds.

This publication extends our research characterizing the state of the field. This year’s landscape provides a robust snapshot that primarily aggregates three years of survey data—cumulative data from surveys conducted in 2022, 2023, and 2024, except where noted.

For this research, we define collaboratives as entities that either pool or channel resources from multiple donors to nonprofits. We call them “collaboratives,” “funds,” and “platforms” interchangeably in this report and across our work. We have reached out to over 500 such funds globally over the past three years, and 310 unique collaboratives responded at least once to our survey between 2022 and 2024. (See the “Research Methodology” below for more on our approach.) While this is a strong response rate, we acknowledge that there are many initiatives and organizations whose input we didn’t capture. We also convened survey respondents each year to discuss the findings and gather more insights.

Key Characteristics of Philanthropic Collaboratives

The field is growing

The number of funder collaboratives is growing. Nearly half of the collaboratives responding to our survey were founded in the last decade. Fewer collaboratives launched in the most recent year of our study: of the 300-plus respondents, just four collaboratives launched in 2023, compared to 18 in 2022 and 19 in 2021. Still, it may be too soon to call this a trend; the decline may simply indicate a lag in our awareness of newer collaboratives or in their response rates. Nevertheless, it’s data we’ll be keeping a close eye on.

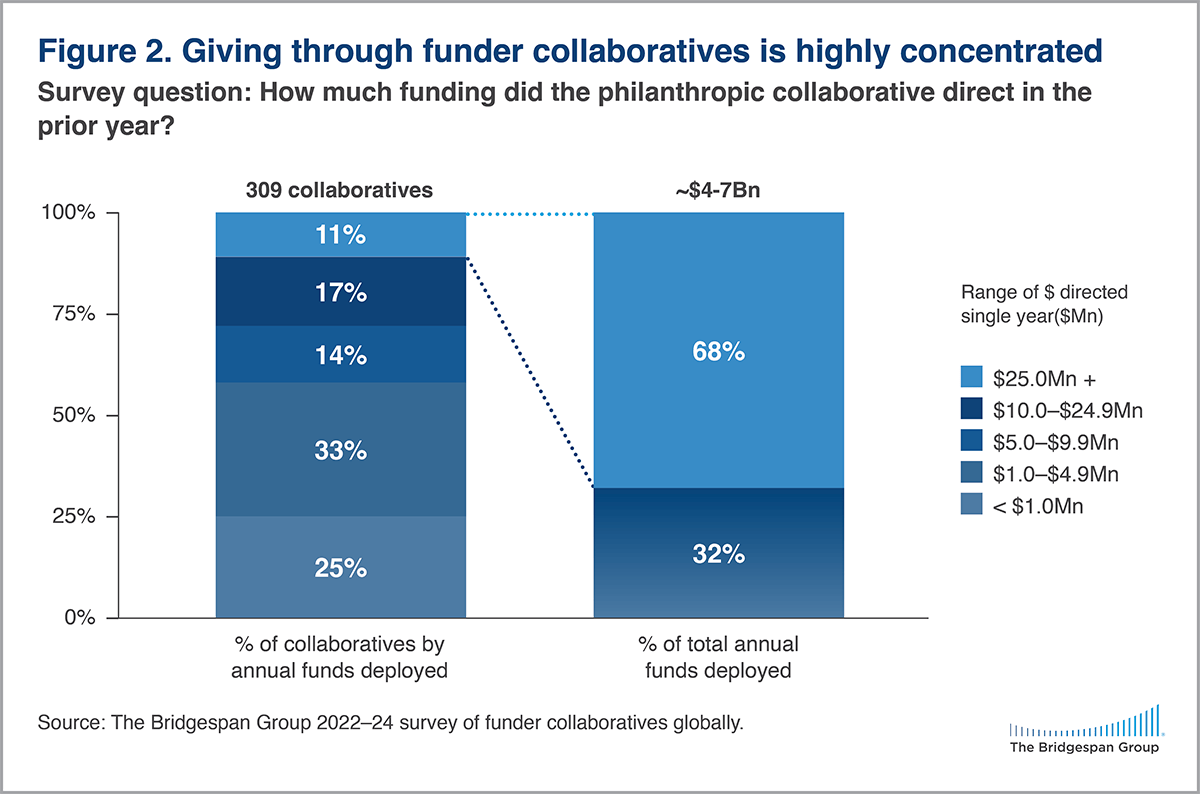

That said, these vehicles have become significant actors in the philanthropic landscape: our survey respondents collectively deploy $4–7 billion per year globally. That’s a lot of money, yet it’s relatively small compared to the $103.5 billion in US foundation giving in 2023, according to the most recent estimates from Giving USA 2024: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2023.

Giving through these platforms is highly concentrated. The 33 collaboratives in our sample that each deployed more than $25 million per year collectively accounted for over two-thirds (68 percent) of overall funding.

When asked which types of donors accounted for most of their funding, 44 percent of the funds cited institutional foundations. Only 16 percent indicated individual donors. Larger funds were more likely to rely on individual donors. Twenty-one percent of collaboratives that gave over $25 million annually reported individual donors as their primary source compared to 15 percent for smaller funds.

There were geographic variations as well. Collaborative funds exclusively serving North America were more likely to cite institutional foundations comprising most of their funding (51 percent). In contrast, only 36 percent of funds serving other regions (which includes funds serving North America plus another region) cited institutional foundations, relying more heavily on a mix of institutional, government/bilateral/multilateral, and individual funders.

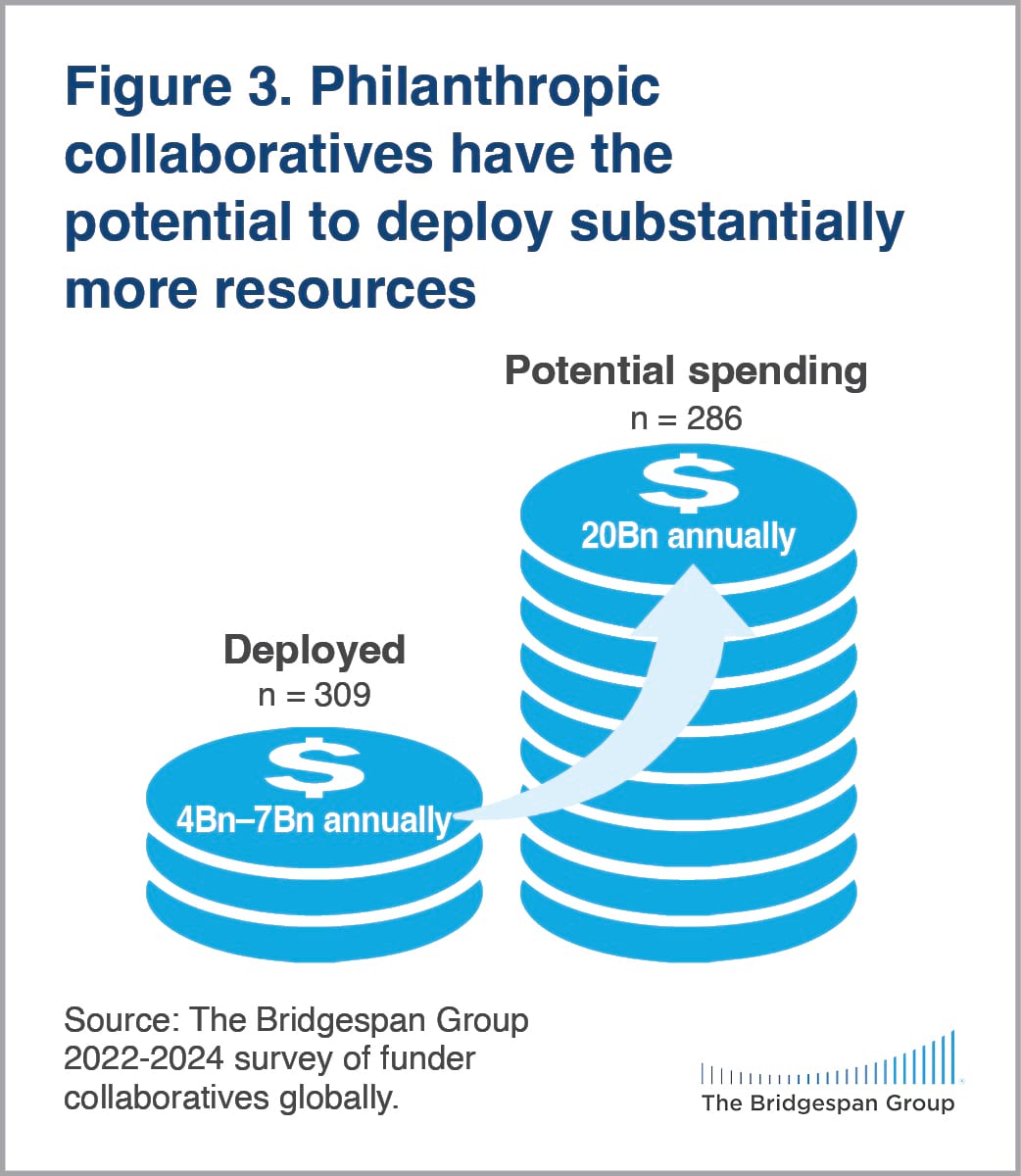

Collaboratives have the potential to do more

The collaboratives that responded to our survey reported they could deploy nearly three to five times the resources they currently direct annually—as much as $20 billion in the coming year—were fundraising not a constraint.

The collaboratives that responded to our survey reported they could deploy nearly three to five times the resources they currently direct annually—as much as $20 billion in the coming year—were fundraising not a constraint.

But fundraising is a constraint. In our 2022 and 2023 surveys, collaborative leaders cited as barriers insufficient awareness among donors of the value of collaborative funds and donors’ preference for giving directly to organizations. Collaboratives also indicated that their own capacity to fundraise is a constraining factor, given the resources needed to cultivate and maintain a larger donor base.

Collaboratives are active around the world—and on a range of issues

Collaboratives are active globally—with nearly one-third of respondents working across multiple regions. There is growing momentum behind philanthropic collaboratives in India, in Africa, and more broadly across the Global South.

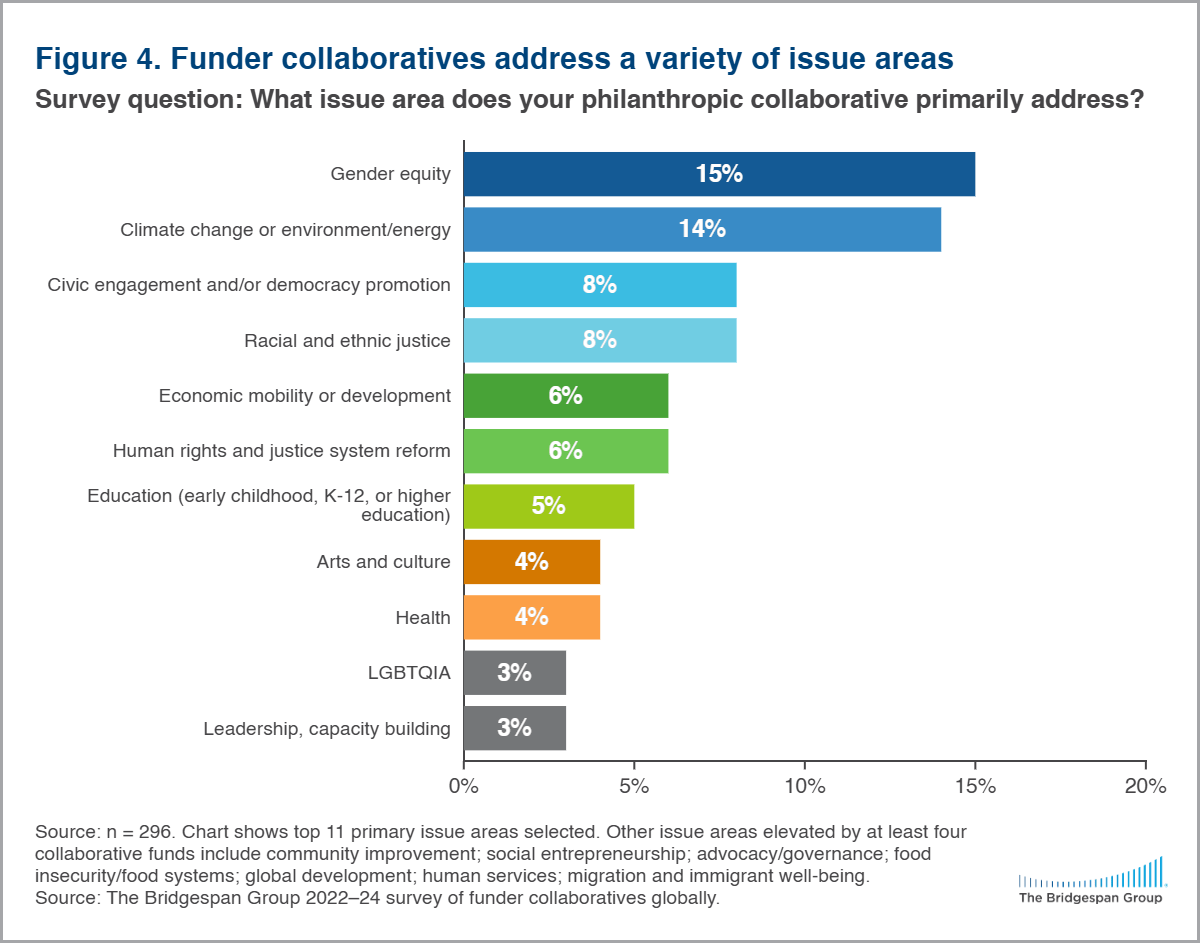

Collectively, funds advance a wide array of impact goals. Their primary issue areas span some two dozen, with some notable concentrations. Fifteen percent cited gender equity, as their primary issue area, 14 percent named climate change or environment/energy, 8 percent named civic engagement and/or democracy promotion, and 8 percent named racial and ethnic justice.

In the past few years, we’ve seen an increase in climate-focused funds. Nearly a quarter of collaboratives founded since 2020 name climate change or environment/energy as their primary issue area.

Collaboratives with a primary focus on equity and justice were less well represented among the larger funds, suggesting they face steeper fundraising barriers than collaboratives with other primary issue areas. More specifically, among the 33 funds we surveyed that give more than $25 million annually, only two named gender equity and only one named racial and ethnic justice as their primary issue areas.

Each respondent reported a median of six secondary issue areas, reflecting how these funds often work across issues. Working in this crosscutting way can create a barrier to funding. In our 2022 and 2023 surveys, many funds highlighted the challenge of not fitting cleanly into issue-focused funders’ strategies.

In our past research, we highlighted that how collaboratives go about achieving change (their “investment thesis”) is as critical to their operations as what issue they work on. For funder collaboratives, the how is often through supporting multi-stakeholder efforts, instead of primarily focusing on regranting dollars to individual organizations. Sixty-three percent of the collaboratives we surveyed support a range of efforts and organizations working on a shared goal—for example, resourcing community-driven change or cross-sector coalitions, fields, and/or movements. That’s more than four times the number of collaboratives that primarily prioritize supporting individual organizations or primarily prioritize supporting place-based change.

Collaboratives prioritize equity and diverse leadership

“Collaborative funds fill a clear gap,” said one fund leader. “They resource and build the capacity of organizations advocating for and organizing underserved constituencies.”

Indeed, in our data from 2021 to 2023, more than 80 percent of respondents described racial and ethnic equity and about 70 percent described gender equity as a “core” or an “intentional” focus of their work. This focus manifests in a variety of ways, from the funds’ primary issue areas—the concentration of funds focusing on either gender equity or racial and ethnic justice noted above—to their leadership, their grantees’ leadership, and their grantmaking methods.

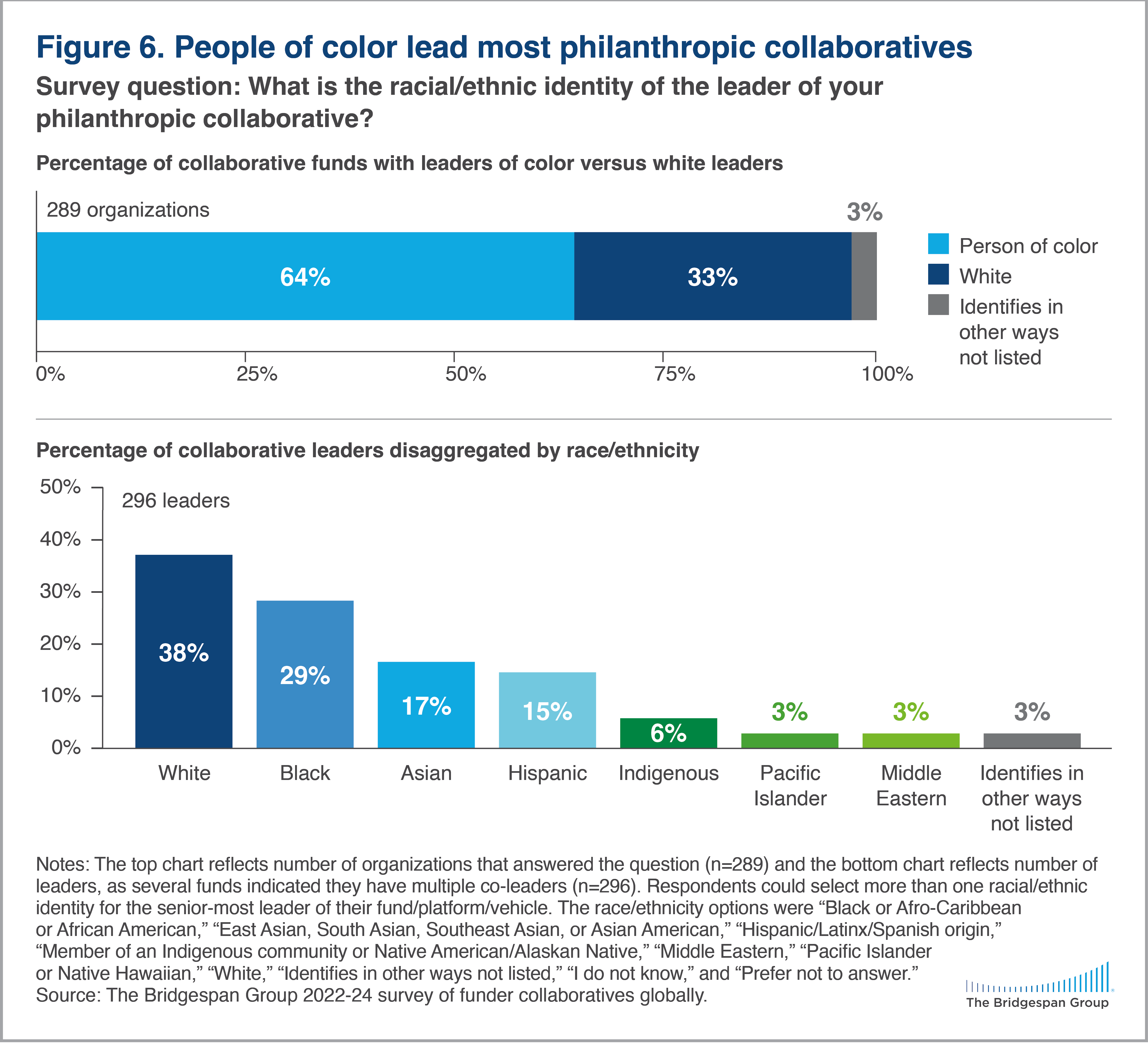

People of color and/or women are far more likely to lead collaboratives than across traditional philanthropy. Women lead or co-lead over two-thirds of the funds we researched (70 percent). Nonbinary individuals lead 5 percent of the funds in our survey. Sixty-four percent reported that their senior-most leader—or, for collaborative funds with a co-leadership model, at least one of their co-leaders—identifies as a person of color. In comparison, 63 percent of US foundation CEOs are women and 17 percent are people of color, according to 2024 research by the Council on Foundations.

We also examined the responses by leader, as opposed to by fund, to disaggregate by race and ethnicity while accommodating multiple co-leaders and leaders who identify with multiple races/ethnicities.

Collaboratives shift power and strengthen grantees

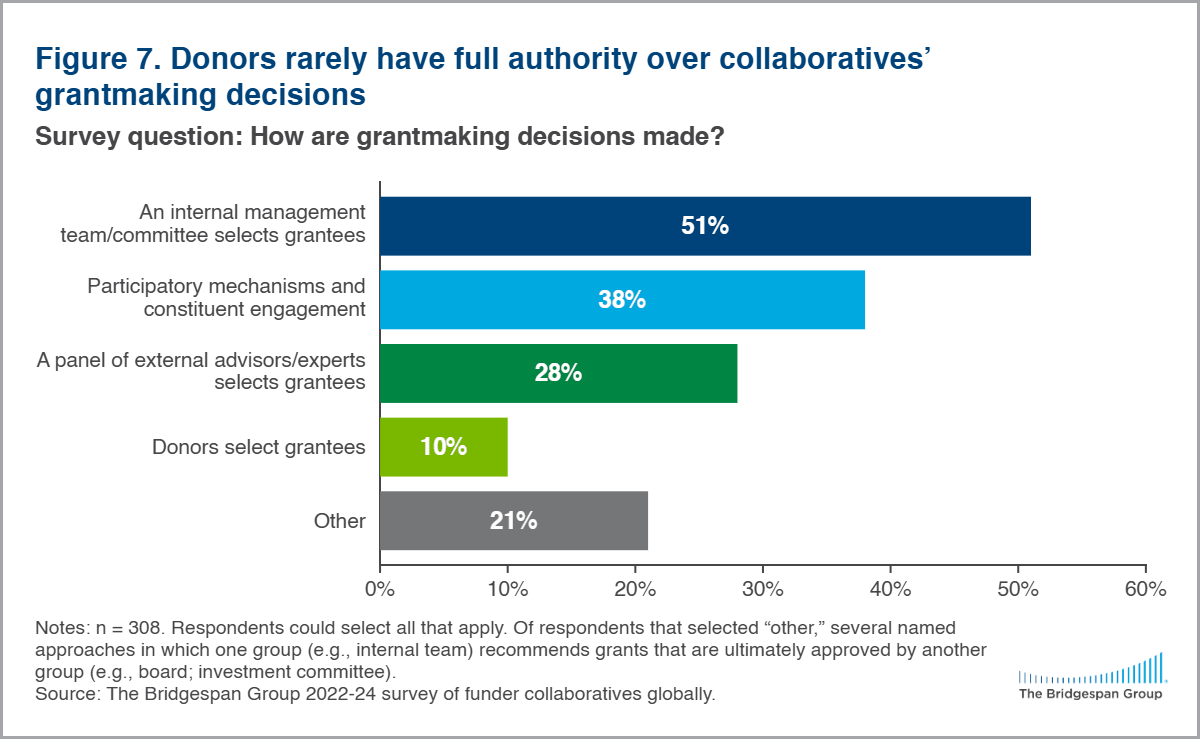

Nearly 40 percent of collaboratives use participatory processes for grantmaking decisions—handing decision-making power to nonprofit leaders and community groups on the receiving end of grantmaking. Such practices are less common among foundations. A 2021 University of Washington study that surveyed high-level foundation staff at 148 large US foundations found that only 10 percent allow grantees or community members most affected by the foundation’s funding to decide how to allocate grant funds.

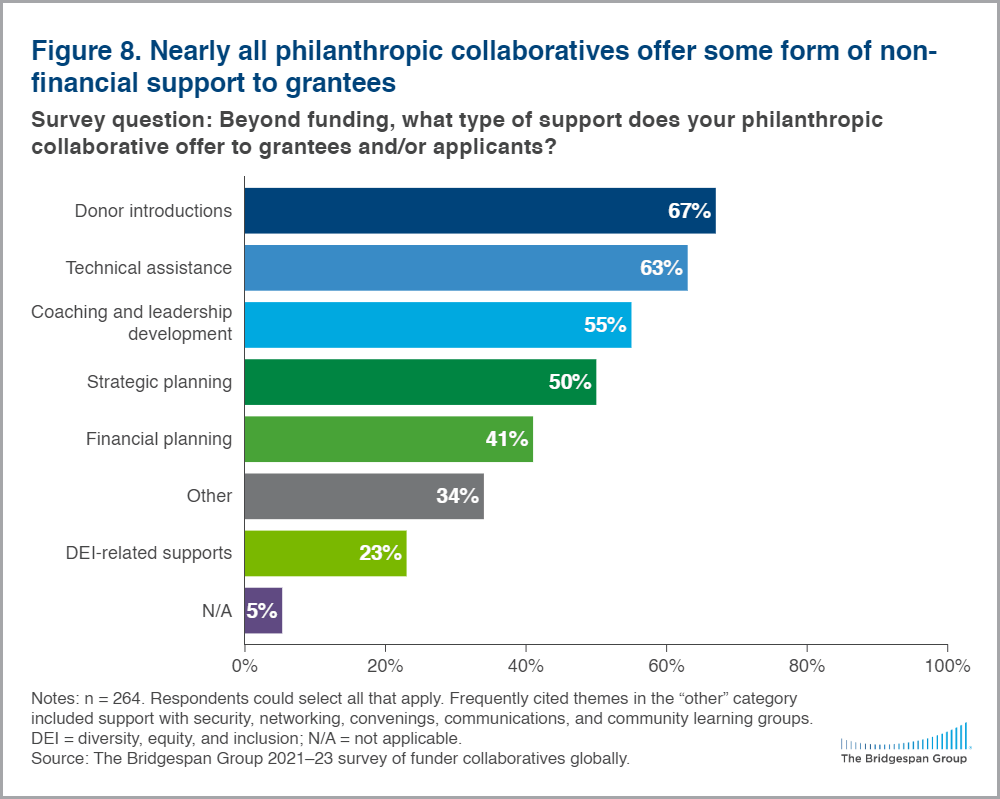

More than half of the collaboratives we surveyed provide some form of unrestricted support (noting they either offer grants that are totally unrestricted or are totally unrestricted but funding a strategy or plan). By comparison, the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s analysis of its Grantee Perception Reports (GPR) notes that between 2021 and 2022, the average proportion of grantees in the GPR receiving general operating support was 30 percent. Nearly all the collaboratives we surveyed (95 percent) between 2021 and 2023 indicated that they offer some form of nonfinancial support to grantees. Donor introductions, technical assistance, coaching, and leadership development are the most common.

Collaboratives have a wide variety of cost structures

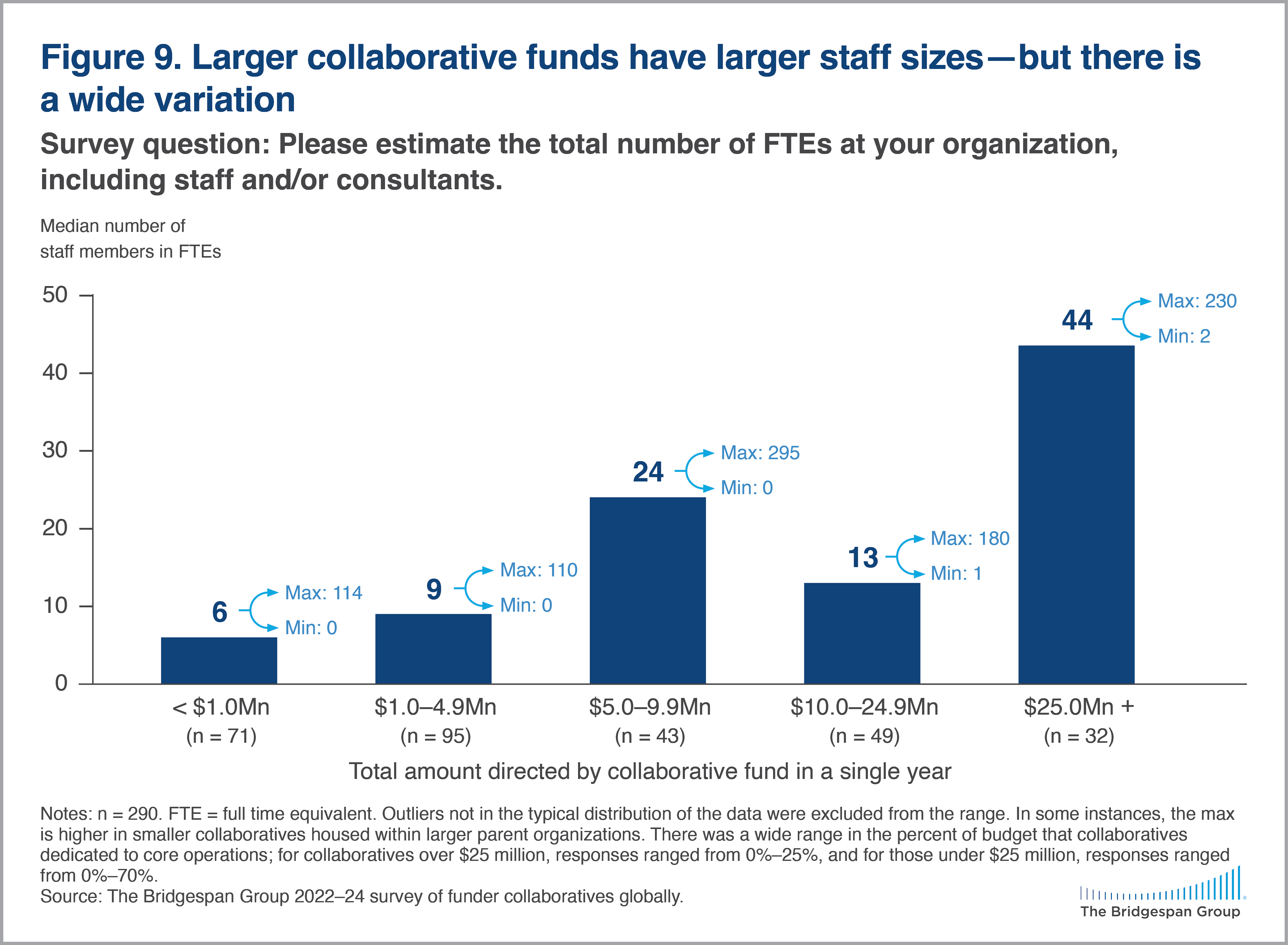

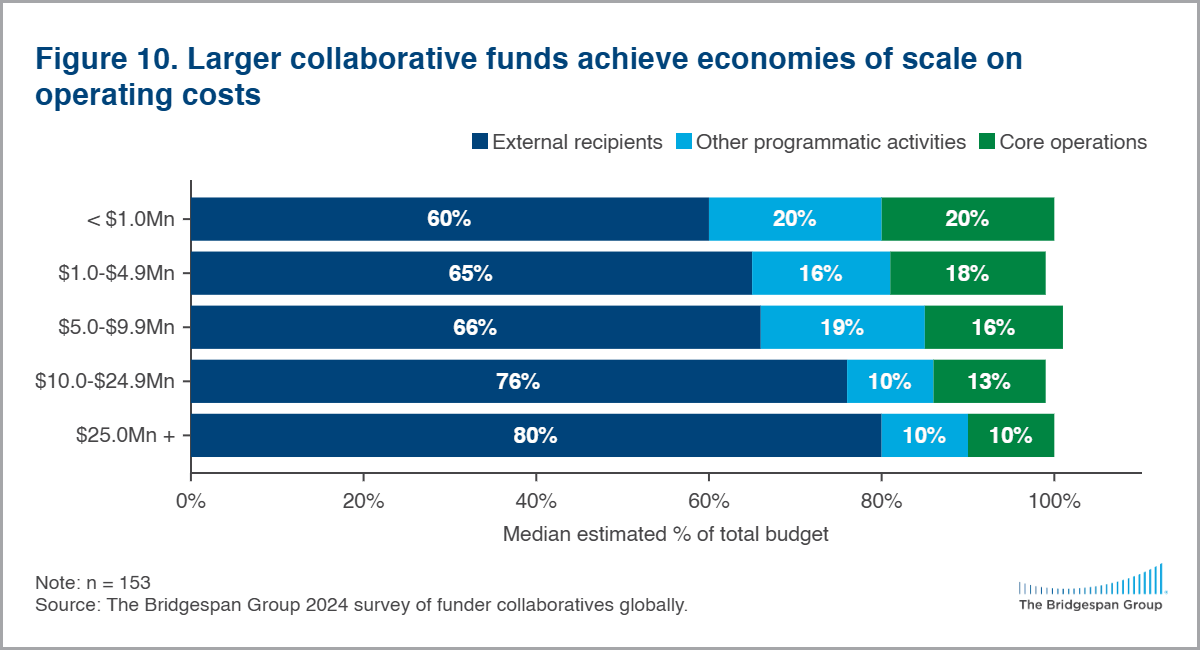

Funder collaboratives invest varying resources in operations. Our 2024 survey respondents have a median staff of 12 full-time equivalents (FTEs), with a median of 15 percent of their budgets going toward core operations (e.g., finance, administration, HR, executive leadership/management), and a median of 15 percent of their budgets going toward other programmatic activities beyond the funds directed to recipients outside of their organizations. There is a large amount of variation in these figures. A collaborative’s scale of grantmaking and its programmatic approach influence both its staff size and cost structure—for example, the depth and breadth of its sourcing and diligence, along with the nonfinancial support it provides to grantees and the broader field.

Collaboratives that direct $25 million or more per year typically have more staff, a median of 44 FTEs compared to 11 FTEs for those directing under $25 million. Funds larger than $25 million also allocate a lower proportion of their budgets to core operations and other programmatic work—each a median of 5 percentage points less than the median for smaller funds.

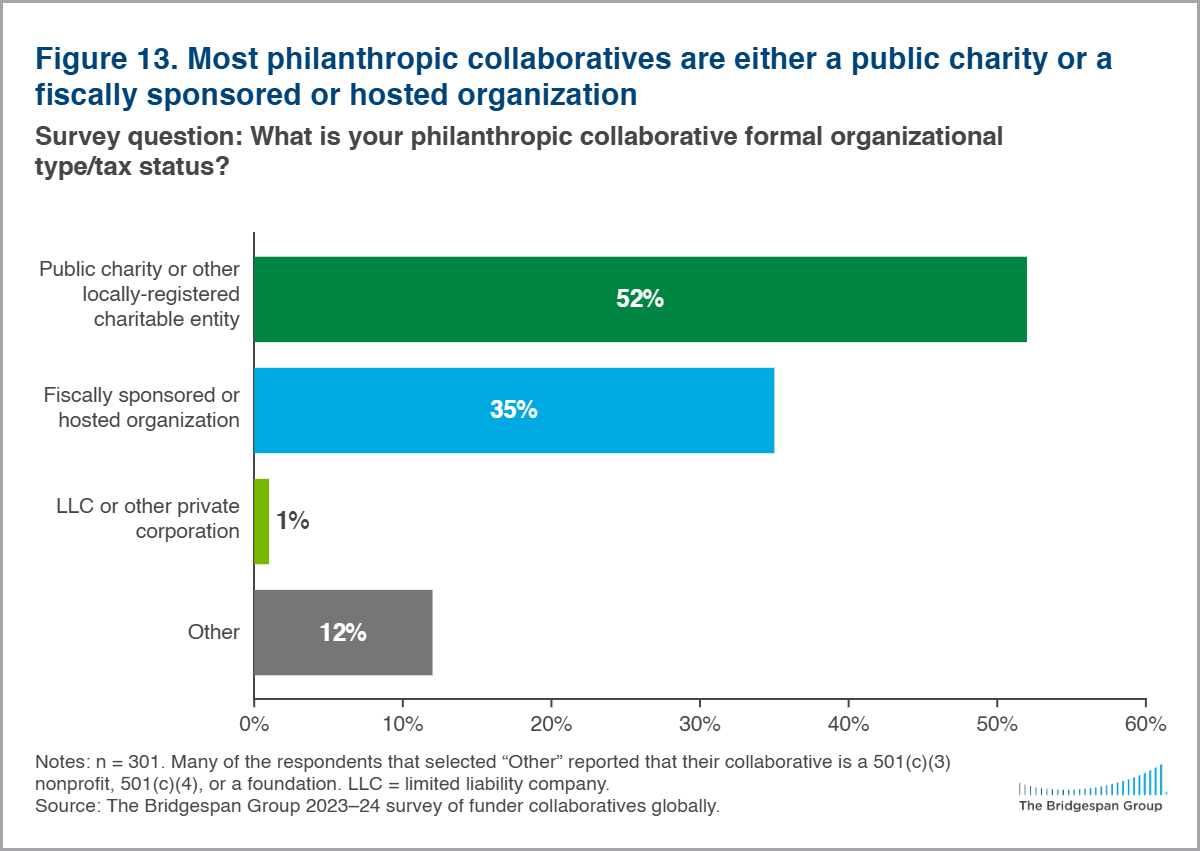

In our 2023 and 2024 surveys, we gathered information on collaboratives’ founding stories, their operations, and their structures.

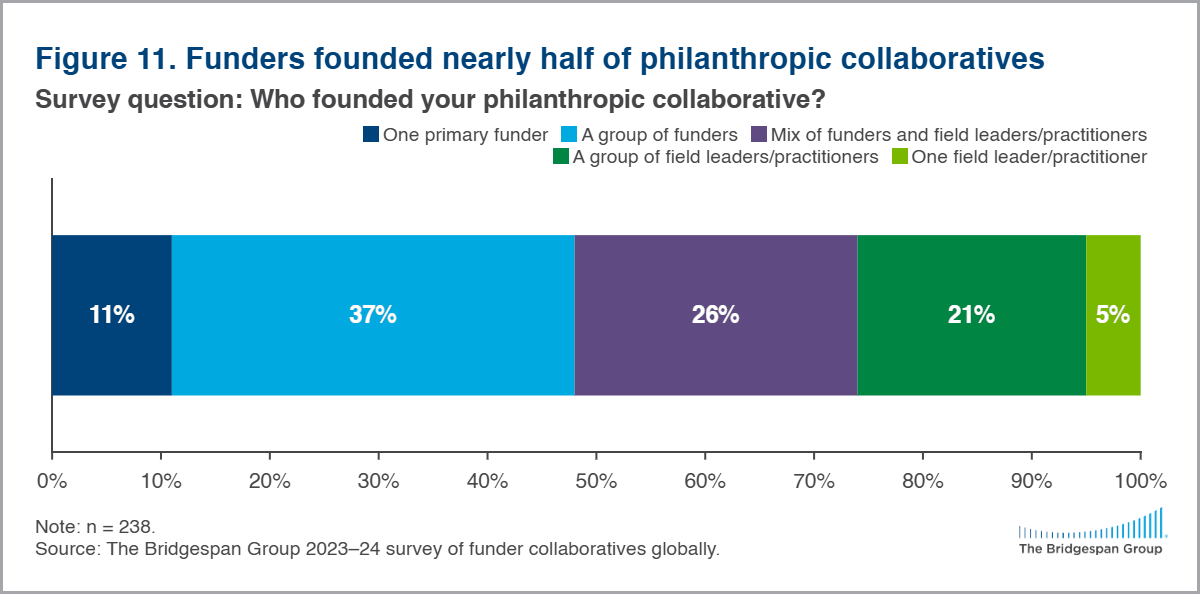

Founding stories. Funders founded nearly half of the collaboratives we surveyed. Field leaders/practitioners founded 27 percent. The remainder involved a mix of funders and field leaders.

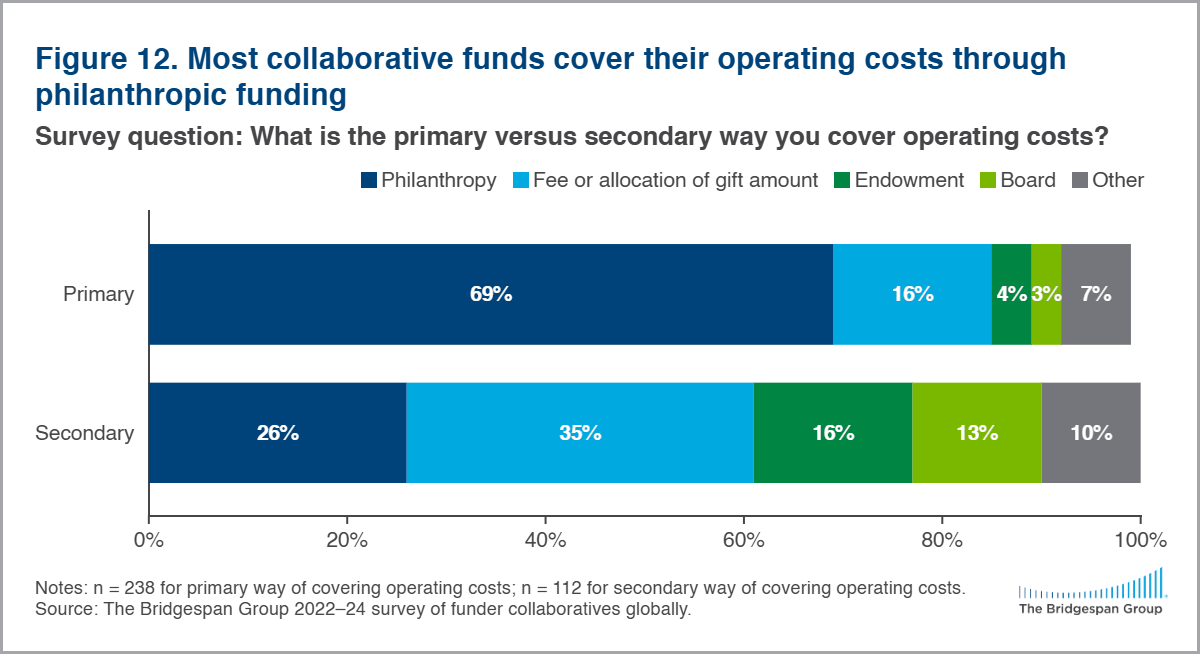

Operating cost structure. Given the many questions collaboratives ask us about pathways to fully fund their costs, the 2023 and 2024 surveys dug into this topic. Most responding collaboratives reported that their operating costs were covered for their first three to five years. Approximately 75 percent had such expenses at least partially covered. Perhaps unsurprisingly, larger funds—those that have grown to over $25 million in annual grantmaking—were even more likely (90 percent) to have had their initial operating costs at least partially covered.

Collaboratives would like to invest more in measurement and learning

Collaborative leaders regularly tell us that they would like to invest more in measurement, evaluation, and learning. Our earlier survey data showed nearly 70 percent of collaboratives flagged measurement and learning as a critical area for investment—second only to strengthening their teams. Given this need in the field, we decided to probe a bit deeper in our 2023 survey.

We also published an article in 2024 to highlight promising practices for how philanthropic collaboratives can effectively measure, evaluate, and learn in the pursuit of greater impact. Collaboratives operate in a unique context—at the intersection of donors, grantees, and fields or systems in which they operate. While grantmaking is often core to a collaborative’s strategy, its impact is ideally greater than the sum of its grants and grantees. Collaboratives therefore often seek to understand their impact on both grantees and donors. For many, their measurement approaches also consider the system or field level.

Directions Forward

We discussed the survey results with over 50 sector leaders in 2024, and over 100 sector leaders in 2023. As they spoke about priorities for the field going forward, a few themes surfaced consistently.

Increase awareness, especially in an era of heightened perceptions of reputational and legal risk. Fund leaders consistently point to the need to better communicate the value of their work to current and prospective funders—including the operational resources it takes to effectively carry out their work. Leaders underscored the particular importance of this given the current political environment. Many funders expressed greater risk aversion amid the strengthening of public narratives pushing back against diversity, equity, and inclusion. A recent report from Ganguli Associates highlights “risk diversification” as an enabling factor of a healthy collaborative ecosystem—noting that giving through a fiscally sponsored collaborative can transfer risk from donors to the collaborative and the sponsoring organizations.

Among the ideas offered for increasing awareness and understanding:

- Develop more accessible lists of funds (such as this philanthropic collaborations database on Bridgespan.org and resources hosted by the Gates Foundation)

- Advance donor norms around incorporating collaborative funds in sourcing and diligence processes

- Hold more philanthropy convenings to showcase collaborative funds

- Conduct more applied studies to better understand these vehicles

Break down identity-based barriers to capital. Similar to the well-documented disparities in funding for nonprofits led by people of color and African-led nongovernmental organizations (although more recent data suggests change is slowly afoot), funds led by people with historically marginalized identities (including race, ethnicity, and gender) face additional barriers as they seek to connect with funders, build rapport, and secure sustainable funding. This was unsurprising to leaders we spoke with, many of whom have experienced these barriers directly. At the same time, there was clear acknowledgment that removing those barriers requires funders to focus specifically on ways to source a broad range of funds, such as by:

- Incorporating an equity lens in defining the goals of their portfolios

- Counteracting biases at each stage of the process

- Seeking feedback from equity-oriented leaders to ensure they can learn and improve over time

Navigate pivot points. Many fund leaders shared that they are wrestling with how to navigate major pivot points in their collaboratives’ lifecycles while effectively advancing their work, and engaging donors and grantee partners through these points of transition. These include leadership transitions, initial operating support from anchor donors ending, and bringing on new donors and grantees.

Increase understanding of funds’ operating model choices. In our research, conversations, and advisory work with collaborative leaders, we continue to hear how funds organize their work and operate their teams. Fund leaders expressed an interest in better understanding how:

- Operational capabilities compare across peer collaboratives

- Capabilities and operating models vary according to strategic choices and types of work

- To best communicate related costs to donors and secure support for these costs (especially after the initial 3–5 years of a collaborative’s lifecycle)

We hope these findings are valuable to leaders of current collaboratives, leaders of potential collaboratives, and donors interested in learning more about how collaboratives operate. We look forward to continuing this conversation and highlighting additional research from the field as it becomes available, to help unlock much more capital for social change.

If you are a part of a platform that you believe should be included in future research, please use the form at the bottom of this web page to let us know about your philanthropic collaborative.

Research Methodology

Between 2022 and 2024, we reached out to over 500 philanthropic collaboratives to complete our annual surveys and received responses from 310 unique collaboratives over this three-year period. Each year, we expanded the previous year’s outreach list with desk research, referrals from organizations and leaders in The Bridgespan Group’s broader network, and direct outreach from potential respondents. Our outreach approach (led out of Bridgespan’s US-based offices) yielded an overall survey sample favoring funds based in North America. Each year the respondents had six weeks to complete the online survey during the summers of 2022, 2023, and 2024. In cases where a collaborative or a leader responded to multiple surveys, we used only their most recent response in our data aggregation. In cases where a survey question was not asked in 2024, but was asked in prior years, we used data from 2021–2023.

We also held follow-up group discussions in the second half of every year. Each year, 50–100 of the survey respondents attended these discussions in which they reviewed the survey data and provided further input. Additionally, in 2022, we spent a full day with leaders of 12 of the largest collaboratives to surface additional insights. And, in 2023, we attended the Global Summit of Collaborative Funds, co-hosted by the Gates Foundation and Philanthropy Together, where we had a chance to share insights and engage with many collaborative practitioners.

We defined philanthropic collaboratives broadly as entities that either pool or direct philanthropic giving from multiple donors to nonprofit organizations. Thus, our survey sample spans large capital aggregators; organizations that do not pool resources but instead provide a “platform” for donors to source options; and organizations, sometimes called public foundations, that depend on annual giving for their grants. In our search for examples, we sought to include funds with a racial or gender equity focus.

We did not include community foundations, writ large, because it is hard to determine the proportion of their giving that is donor-directed through donor-advised funds, as opposed to funds pooled or influenced by the foundations. We did, however, include a small number of special-purpose community foundation funds. We did not include COVID-19 funds or other time-limited disaster-relief efforts.

Acknowledgments

Bridgespan is grateful to the staff members of the many collaborative funds who participated in the survey and shared their information with us to help deepen the collective knowledge base about these philanthropic platforms.

The Bridgespan team that developed this research and report includes Hannah Aragon, Wendy Castillo, Gayle Martin, Carole Matthews, Alison Powell, Kate Sieler, and Zachary Slobig.

More on Philanthropic Collaboration

Bridgespan publications and Resources

- Philanthropic Collaborations Database (non-exhaustive)

- “Learning From a Decade of Collaborative Philanthropy” (SSIR.org, 2025)

- “Centering the Grantee Experience: A Path to Differentiation for Intermediary Funds” (The Center for Effective Philanthropy, 2024)

- Want to Fund in the Global South? Philanthropic Collaboratives Can Help (2024)

- The Growing Momentum Behind Philanthropic Collaboratives in India (2024)

- Philanthropic Collaborations in Africa and Their Unique Potential (2024)

- Releasing the Potential of Philanthropic Collaborations (results from our 2021 survey)

- Philanthropic Collaboratives in India: The Power of Many (2020)

- “How Philanthropic Collaborations Succeed, and Why they Fail” (SSIR.org, 2019)

- Are Funder Collaboratives Valuable? A Research Study (2019)

- “Value of Collaboration Research Study: Literature Review on Funder Collaboration” (2019)

- “Collaborating Towards Kindergarten Readiness at Scale: A Funder Group Case Study” (2018)

- Four Pathways to Greater Giving (discusses the potential for funder collaboration to unlock capital, 2018)

Additional resources

- Gates Foundation Collaborative Funds resource hub (Gates Foundation Philanthropic Partnerships)

- “Reimagining Collaborative Philanthropy” (SSIR.org, 2025)

- Collection of stories and insights on collaborative funds (Giving Compass and Philanthropy Together)

- Bridging the Gap: Grantee Perspectives on Intermediary Funders (The Center for Effective Philanthropy, 2024)

- “Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Intermediary Funds” (Hilary Pennington, blog for The Center for Effective Philanthropy, 2024)

- Strengthening and Supporting the Enabling Infrastructure for Collaborative Funds, (Ganguli Associates, 2024)

- Issue area briefs on gender inequality (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Shake the Table, and The Bridgespan Group, 2023), the climate crisis (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Climate Leadership Initiative, 2022), and democracy (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Funders Committee for Civic Participation, and The Bridgespan Group, 2024)

- “Frontline-Serving Intermediaries: An Underutilized Tool for Philanthropy” (Arabella Advisors, JPB Foundation, and Windward Fund, 2022)

- “Funder Collaboratives: A Topic Brief for Donors” (Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, 2021)

- Funder Collaborative Toolkit (Fund for Shared Insight, 2021)

- “Collective Impact” (SSIR.org, 2011)

- Issue Funds and Intermediaries, Giving Compass

- Funder Collaboratives: Why and How Funders Work Together (GrantCraft, 2009)

Let Us Know About Your Philanthropic Collaborative

Fill out the form below to let us know about a philanthropic collaborative that should be added to our list.