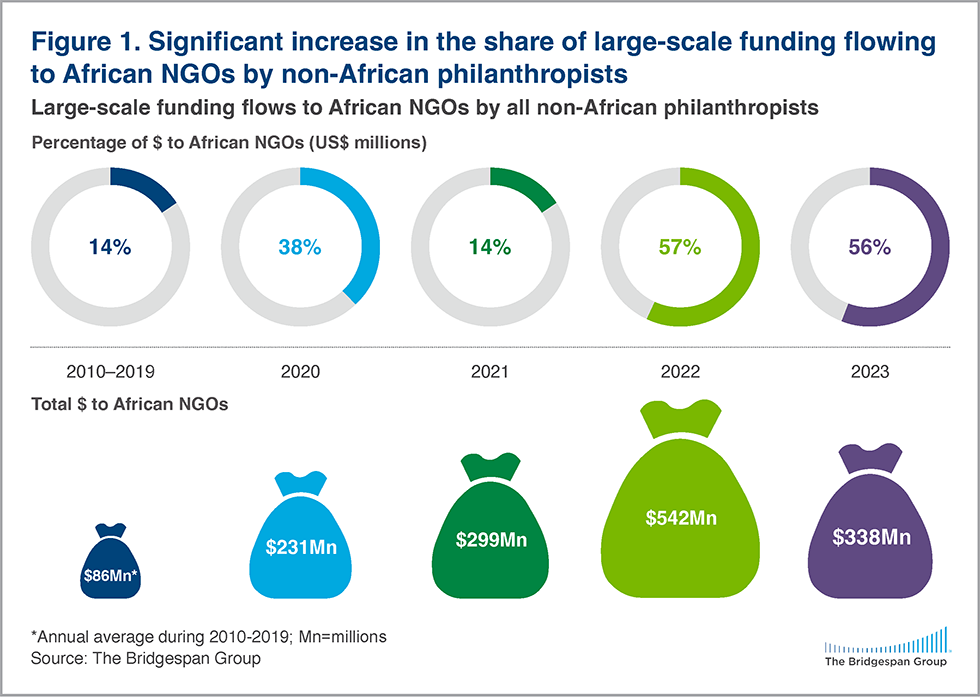

In the years since the COVID-19 pandemic threatened African lives and livelihoods on a continental scale, philanthropists appear to be shifting their funding practices. The tide may be turning on the previous decade, when just 14 percent of large gifts by non-African funders went to African non-government organisations (NGOs). 1, 2

When The Bridgespan Group first conducted research into large-scale giving from 2010 to 2019, we found that 58 percent of large gifts from non-African philanthropists went to non-African NGOs. We later revisited the data to include the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 and observed a surge in giving to the public sector to help with COVID-19 relief, particularly in 2021.

Now, the pattern of the last decade has begun to be flipped on its head. When we updated the data to include the years 2022 and 2023, we found large gifts from non-African funders predominantly going to African NGOs. This stands in stark contrast to the longstanding history of funders directing capital to non-African organisations operating on the continent.

Intrigued, we dug deeper and found two particular organisations shifting their large-scale giving towards African NGOs, as we describe below. For them, the shift was no accident. “The increase in the Mastercard Foundation’s partnerships in Africa has been very intentional,” says Tade Aina, chief impact and research officer at the Mastercard Foundation. “This [intentionality] is evidenced by several actions, including the introduction of targets around supporting young African women and African and Indigenous organisations in Canada. The transformation of the Mastercard Foundation’s operating model, which also established offices in Africa, has enabled the Foundation’s leadership and teams to work closer with our partners.”

The Rise of Global Giving to African NGOs

As borders reopened and lives returned to a new version of normal in the wake of COVID-19, large-scale giving by non-African donors effectively returned to its pre-pandemic numbers both in terms of average grant size and the number of yearly grants given. But the pattern of giving changed from decades-old practice.

From 2010 to 2019, just 14 percent of large-scale giving from non-African funders went to African NGOs. In contrast, this percentage rose to over 55 percent in 2022 and 2023—meaning the $880 million African NGOs received in 2022 and 2023 is more than they received over the entire decade before the pandemic. (See Figure 1.)

Large-Scale Funders Driving the Shift

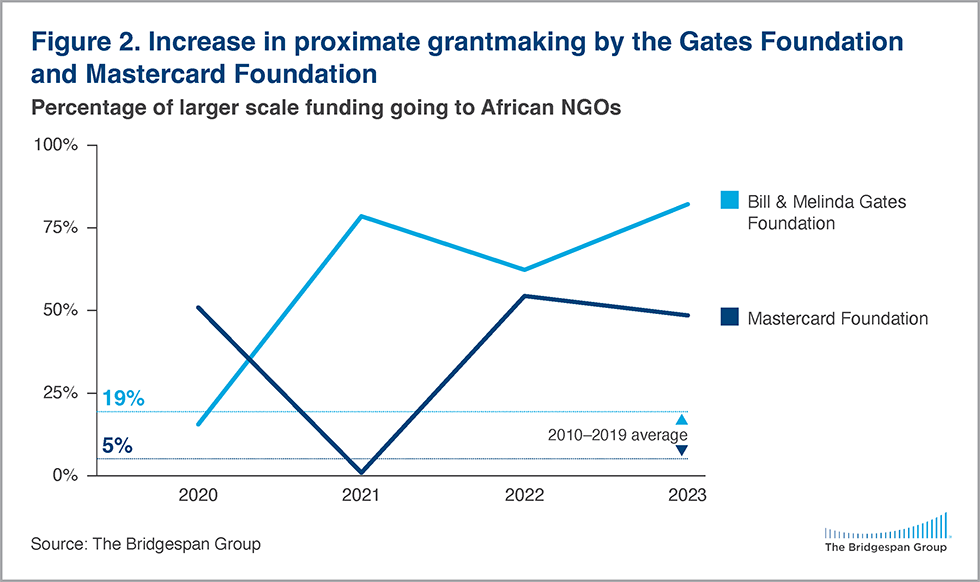

Two large-scale funders—the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Gates Foundation) and Mastercard Foundation—were major reasons why more funding flowed to African NGOs.

In the years between 2010 and 2020, the Gates Foundation gave large-scale gifts in Africa overwhelmingly to non-African organisations. However, from 2021 to 2023, 18 out of 25 grants went directly to African organisations, with $235 million going to Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa. African NGOs received 16 percent of Gates Foundation’s large-scale gifts to the continent in 2020 – and 82 percent in 2023.

The shift in the Gates Foundation’s giving coincides with its adoption of a strategic plan aimed at upholding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in 2021. One of the goals that the Gates Foundation is working towards under the “Partnerships & Voice” pillar of its DEI Commitment is greater engagement with “proximal partners.” The foundation defines proximal partners as those “most deeply connected to the people and places [Gates Foundation’s] work focuses on – whether by location, demographics, lived experience, or community engagement.”

According to the Gates Foundation's 2022 DEI Progress Report, its teams are employing various strategies to amplify support for proximal organisations. These include breaking down larger projects into smaller components to enable collaboration amongst multiple organisations and altering their sub-granting approach to directly fund proximal partners, who may then choose to sub-grant to partners in higher-income countries.

While the Gates Foundation acknowledges in its progress report that there is still more to be done in diversifying its portfolio, it notes some positive developments since implementing the DEI Commitment. Despite the proportion of grants directed to organisations outside the United States or Western Europe remaining below 20 percent in 2022, its portfolio is shifting definitively. For instance, in 2022, 44 percent of the new grants from the Foundation's Agricultural Development program were allocated to proximal partners, compared to 25 percent in 2020. As noted above, our own research has shown significant shifts in the Gates Foundation’s giving in Africa at the $10 million-plus gift level since 2021.

The Mastercard Foundation similarly gave predominantly to non-African NGOs between 2010 and 2019, with just nine out of 54 grants going to African organisations, representing 5 percent of grant dollars. In the pandemic year of 2020, African NGOs received 51 percent of Mastercard Foundation’s large grants in Africa, in dollar terms.

In 2021, Mastercard Foundation announced a $1.5 billion gift to the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) as part of the Saving Lives and Livelihoods Initiative. (We classified Africa CDC as a public sector organisation in our database.) Mastercard Foundation’s proximate giving to African NGOs in 2022 and 2023 rose to 54 percent and 48 percent, respectively, equating to a total of $334 million. Of this, $276 million went to Carnegie Mellon University Africa in Kigali, Rwanda.

The launch of Mastercard Foundation’s Young Africa Works strategy in 2018 was a big part of the shift. Based on learnings and achievements since the foundation’s launch in 2006, the strategy aims to “enable 30 million young people in Africa, especially young women, to secure employment they see as dignified and fulfilling” by the year 2030. To enable this strategy, Mastercard Foundation transformed its operating model to decentralise operations, delegating authority and shifting staff and resources to the seven African countries where it operates. The foundation also committed to ensuring that at least 75 percent of its partnerships in Africa are with African organisations as part of its long-term path to sustainable impact.

For both the Gates Foundation and Mastercard Foundation, there was a significant shift towards localised large-scale giving, with a notable decline in the proportion of funding going to non-African organisations. As more non-African organisations engage in conversations about shifting power and resources from capital-rich geographies to local organisations and people, this shift in giving may serve as a catalyst that inspires non-African NGOs to reimagine their operating models in a way that advances equity and facilitates a shift of power locally. It’s still too early to know, however, whether our data represent a sector-wide trend.

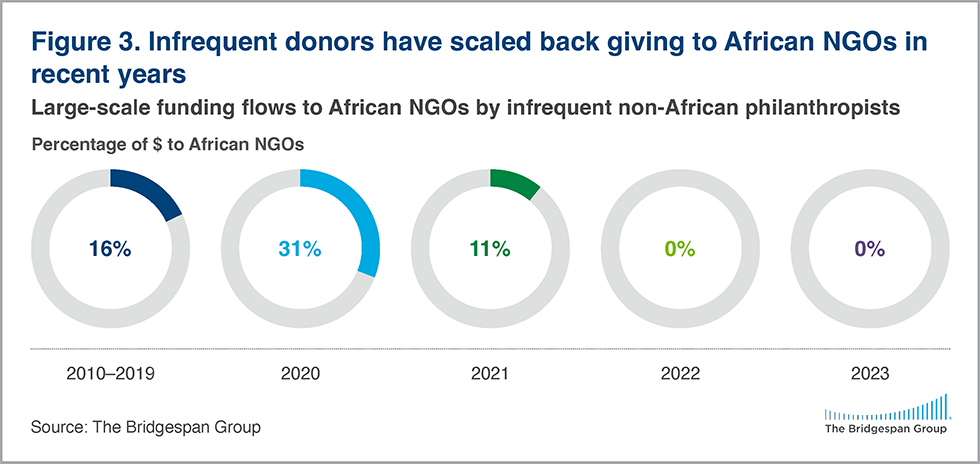

Trends Amongst Less Frequent Large-Scale Donors

The Gates Foundation and Mastercard Foundation are amongst seven consistent large-scale donors in Africa in our database.3 Our research also identified 27 non-African large-scale donors who have given more infrequently on the continent throughout the research period. In the years since the COVID-19 pandemic, their focus seems to have shifted almost exclusively to non-African NGOs.

Between 2010 and 2019, 16 percent of large-scale gifts from infrequent donors went to African NGOs, 25 percent to non-African NGOs, and the remainder flowed to the public sector and other recipients. In 2020, giving to African NGOs rose to 31 percent. However, in 2022 and 2023, infrequent donors gave no large-scale gifts to African NGOs, with non-African NGOs receiving the vast majority of the grants over those two years.

Challenges to Funding African NGOs

The Gates Foundation and Mastercard Foundation notwithstanding, it seems our previous research into the barriers standing between African NGOs and large-scale grants is holding true for most funders. Many of the funders and experts that we interviewed for that report were unsurprised by the scarcity of funding for African NGOs. The challenges of funding African NGOs tend to be similar for both African and non-African donors.

One challenge is scale because there are relatively few large African NGOs working across multiple countries on the continent. This limits the options donors have in giving to NGOs operating on a pan-African scale. In contrast, non-African NGOs tend to have the largest reach across countries, making them an appealing option.

A legacy of mistrust also persists between donors and African NGOs, possibly arising from the perception that these NGOs have low accountability. While, increasingly, this narrative fails to reflect the reality of effective NGO practices on the continent, it could still contribute to historic and ongoing constraints.

Further, political considerations can influence funding flows. Most large-scale giving to African NGOs is focused on basic needs, which allows donors to steer clear of causes that may carry more political risk. However, it may also limit the breadth of organisations considered for such funding. Non-African donors specifically also face other unique challenges such as cross-border legal requirements, making giving to non-African organisations an easier alternative.

The Growing Role of Collaborative Funds

The term “collaborative funds” refers to entities that are co-created by three or more independent actors, including at least one philanthropist or philanthropy. Collaboratives pursue a shared vision and strategy for achieving social impact, using common (pooled) resources and prearranged governance mechanisms. Often, aside from grantmaking, collaboratives work to build the capacity and connectedness of grantees to the benefit of the field and broader ecosystem. An evolving alternative to the philanthropic status quo, collaboratives tend to be experts in channeling resources to proximate leaders—those with lived experience and local knowledge—and local communities. However, research shows that collaboratives in the Global South tend to be underfunded, therefore limiting their scale.

Despite this, collaboratives are a means to address some of the challenges of funding African NGOs by enabling donors to give across borders with less friction. Collaboratives may come to serve as a powerful vehicle in the large-scale giving strategy of non-African funders, particularly in the case of those seeking to move into a new issue area or geography. With more and more evidence that collaboratives bring increased efficiency, effectiveness, and engagement, their growing appeal links to the rising awareness in philanthropy of the power of proximity and trusting those closest to the problem to design and implement the solutions that maximise impact.

For this update, to align with the methodology of our previous research, we opted not to factor in large-scale giving from collaboratives to African NGOs.

A Shift Worth Watching

Conversations about centring proximity in grantmaking have been gaining traction in philanthropic circles over recent years. While it considers only large-scale philanthropy, our data shows that these conversations are leading to tangible action. Long-overlooked African NGOs are finally stepping into the spotlight, as funders consciously redirect their support, armed with strategic plans and firm commitments around funding African organisations. As we eagerly observe this evolving landscape, questions arise: Will this transformative trend stand the test of time? And will this shift towards proximate grantmaking becoming a sector-wide phenomenon?

Research Methodology

- To assemble and update the database, we used information from publicly available sources such as foundation websites and news articles.

- We selected $10 million as the threshold for grant size amongst non-African donors to be included in the sample.

- We focused on gifts to “social change,” using a definition adapted from The Bridgespan Group’s “big bets” research in the United States. Of note, our definition excludes gifts to arts institutions and religious causes, and includes gifts to academic institutions.

- We focused on large-scale gifts for a single organisation or a handful of organisations with a common goal; however, there are a few exceptions.

- We did not differentiate between individuals and their foundation when identifying grants. While research suggests that many donors make some gifts as individuals and others from their foundations, this distinction was often not clear enough in the source material (primarily news articles) to enable us to distinguish between giving vehicles on a gift-by-gift basis.

- Large-scale gifts from joint efforts (or collaborative funders) have been excluded from our updated database, in keeping with the methodology of our initial database.

- To determine the total amount of the gift in USD, we used the exchange rate from the month and year when the grant was made and rounded numbers where appropriate. Where it was unclear when the gift was donated, the annual average exchange rate was applied.

- We allocated the full amount to Africa for large-scale gifts to multiple continents where no detail is given on how the gift was divided between recipient continents.

- For the purposes of determining recipient types, we considered only the direct recipients of the gifts. We defined recipient types as follows:

- African organisation: Organisations that are headquartered in a country in Africa, including NGOs and academic institutions.

- Non-African organisation: Organisations founded and headquartered outside Africa, including INGOs, foreign academic institutions, and multilaterals.

- Operating foundation: A foundation that makes direct expenditures and implements its own programs rather than making grants to another organisation.

- Public sector: State or local government entities such as ministries, departments, public hospitals, and government relief programs, as well as private-public partnerships.

- Other: Giving to social businesses (e.g., microfinance institutions), money pledged to particular uses where the ultimate recipient has not yet been identified (particularly special purpose funds), and gifts made to unspecified uses.

- Where we found new data covering past study periods from 2010 to 2021, we made revisions to our database.