"There’s a Norman Rockwell picture of rural America: white picket fences, everyone goes to church, and everyone helps the person next door. A great deal of that is true, but poverty is not seen in rural areas. Behind all those things, there is a great deal of poverty."[1]

The depiction of poverty in America has changed dramatically over the past hundred years as our nation has transformed into a largely urban, post-industrial economy. Many see poverty as a phenomenon of derelict, industrial inner cities concentrated around the massive public housing works of the early 1970s. This depiction is deceiving. While poverty in rural areas has declined in the post-WWII era, it is still higher than in urban areas. In fact, the most persistent poverty in this country continues to be in rural America.

Like many in the nonprofit sector, the Bridgespan Group has focused much of our work on urban poverty. However, over the past couple of years we have engaged with a handful of rural nonprofits. This limited experience has given us a starting point for knowledge work on the issues rural nonprofits face. In particular, our work with the National Indian Youth Leadership Project (NIYLP), a youth development organization in New Mexico that focuses on positive youth development via experiential service learning, has taught us important lessons about rural nonprofits and whets our appetite for further research.

Our business planning engagement with NIYLP in the summer of 2007 served as an introduction of sorts to the differences between urban and rural nonprofits. The National Indian Youth Leadership Project engaged Bridgespan to develop a business plan for expanding in New Mexico and growing nationally. As we partnered with McClellan “Mac” Hall and his leadership team, we learned about the difficulties of building, replicating, and sustaining a program in rural America. The National Indian Youth Leadership Project has thrived for more than 20 years managing through the peaks and troughs of funding and human resources transitions. And yet, financial sustainability has been a major concern for NYLIP throughout its history.

This paper seeks to build on our work with NIYLP and other organizations and to look more systematically at the financial aspects of rural nonprofit capacity. While there are other important issues to consider for rural nonprofits—including human resources and program models—we believe the flow of money is a good place to start. In these challenging economic times, the issue of nonprofit funding is topical—but for rural nonprofits, it is a chronic reality of life. With NIYLP, we looked at the challenges in securing financial support for a rural nonprofit without a local philanthropic support base. In this paper, we expand the view from one rural nonprofit in New Mexico to a broader look at the data on nonprofit funding in two sample states, New Mexico and California.

This paper lays out some of the facts surrounding rural nonprofit funding in the sample states, including original research comparing rural and urban nonprofits. We also take a preliminary stab—in the interest of seeding a dialogue—at some lessons for both nonprofits and foundations interested in addressing rural issues. While it would be presumptuous to consider our lessons as recipes for success, we hope organizations will consider these lessons as they wrestle with the contemporary questions of how to fund the important work of addressing rural poverty during these tough economic times.

The Rural Funding Gap

While the current economic climate has placed tremendous financial strains on the nonprofit community at large, recent studies have found that nonprofits in rural America face amplified funding challenges. "Compared to their urban counterparts, rural nonprofits are significantly disadvantaged,” says Rachel Swierzewski, a research consultant for the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and the author of a 2007 report on rural philanthropy. “With scarce local funding sources and often insufficient local support systems, rural nonprofits find it incredibly difficult to build strong organizations."[2]

The data on rural nonprofit funding is stark. Consider the rural funding gap in three important realms.

- Federal government funding: In each year between 1994 and 2001, rural areas received between $401 and $648 less per capita than urban areas for community resources, human resources, and national functions.[3]

- Private foundations: A 2006 "analysis of grant making of the top 1,000 U.S. foundations shows that…grants to rural America accounted for only 6.8 percent of overall annual giving by foundations,"[4] even though rural America accounts for 18 percent of the nation’s population and 21 percent of those who live in poverty.[5,6]

- Corporate giving: A 2000 study of giving by 124 Fortune 500 corporations found that rural organizations received only 1.4 percent of the 10,905 grants made.[7]

The scarcity of funding for rural nonprofits means that these organizations—with fewer resources to begin with—must work harder to obtain the money they need to serve rural communities. The result is that rural nonprofits are less able to help disadvantaged residents in rural communities to overcome their challenges.

Challenges Facing Rural Communities

Since 1959, when the first poverty rates were officially recorded, poverty rates in rural areas have consistently exceeded those in urban areas—often by a wide margin.[8] As recently as 2006, the Housing Assistance Council determined that, of the 200 poorest counties in the U.S., all but 11 are nonmetropolitan.[9]

It’s worth noting that, over the past 40 years, the rate of poverty in rural America has dropped significantly from 33 percent in 1959 to 14 percent in 2003. Much of this gain was achieved between 1960 and 1975. While the urban/rural poverty gap has declined from 18 to 2 percent (see graph below),[10] persistent poverty continues to be concentrated in rural counties.[11] In fact, of the 386 counties that have experienced consistently high poverty rates since 1970, 340 are rural.

Child poverty is also concentrated in rural areas. Of the 732 counties experiencing persistent child poverty, 602 are rural.[12] This harsh statistic points to the challenge that rural youth face. They are far more likely to face multi-generational poverty, with their families living in poverty for three or more generations.[13] Indeed, while some rural families have plunged into poverty due to a job loss or other temporary situation,[14] for too many, the cycle of poverty is an endless one.

Understanding the Funding Challenges for Rural Nonprofits

In our efforts to understand the resources available to rural nonprofits and to compare them to their urban counterparts, we chose a partial sample of the nonprofit sector. Specifically, we narrowed our work to youth-serving nonprofits in California and New Mexico to establish two diverse datasets. To conduct our analysis, we:

- Reviewed available nonprofit data from IRS 990 Form returns;

- Asked nonprofits for more detailed information on their funding sources; and

- Conducted interviews with select organizations that have grown to the relatively modest level of $2 million in annual revenue.

The results of our analysis attest to the significant gap between urban and rural nonprofit funding. Rural nonprofits are, on average, 50 percent smaller than urban nonprofits—with $96 to spend per low-income rural youth versus $218 per urban youth. As the graph to the below shows, the difference is consistent across every major funding source.

When we looked at nonprofits by revenue level, our analysis revealed that few rural youth-serving nonprofits were able to attain higher levels of funding. Only 18 percent of rural organizations (versus 28 percent of urban) attained revenues greater than $1 million and only 3 percent (versus 9 percent of urban) had over $3 million (see graph below).

While we would not advocate for revenue as a sole metric of success, it is useful when considering nonprofit capacity. A $1 million nonprofit is just reaching a minimum level of capacity to add specialist staff to its programs, hire professional staff to manage internal operations, and have resources to invest in developing funds for further growth.

Overcoming the Funding Gap

Despite the undeniable funding challenges for rural nonprofits, our research also revealed that a small number of rural nonprofits manage to reach minimum levels of capacity. While there is more work to be done to deepen the field’s knowledge of how to strengthen the rural nonprofit sector, our preliminary work allows us to draw a starting set of hypotheses.

Affiliation with a national network may offer a strategic opportunity—for some.

Our research revealed an apparent relationship between size and national network affiliation. Rural nonprofits affiliated with national networks tended to be larger than their unaffiliated counterparts. Interestingly, this relationship is not evident for urban nonprofits. Why does it appear that national networks aid rural nonprofits differentially? This is a good question for the field to consider.

In the resource-constrained environment in which rural nonprofits operate, a national network may provide valuable leverage that is not required in an urban setting where deeper resource pools are available. A network brand and reputation help to legitimize the organization in both the local community but more significantly, with funders, further a field. According to Ken Quenzer, the president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Boys & Girls Clubs of Fresno County, “We have a tremendous advantage over other nonprofits [not in a network]…I wouldn’t do this work without a network like Boys & Girls Club. BGCA has been a tremendous marketing asset; it’s given us a name, which allows us to raise funds.”

What’s more, the professional development opportunities available through larger networks may help to augment the skills of the relatively small rural nonprofit staff teams, who otherwise might have to switch jobs—at a big cost to the organization—to advance their professional capabilities. Maureen Pierce, CEO of the Boys & Girls Club of the North Valley, highlighted BCGA’s program that “pair[s] up [high potential] management-level staff…with CEOs from different clubs.” Pierce noted that this program and others that focus on developing staff have helped her North Valley club improve its staff retention.

Program services and funding support also enable nonprofit leaders to focus their time on external fund development with confidence that their programs are solid. Pierce commented on the value of “opportunities for sharing best practices and intense training programs, including things like board effectiveness, how to run a teen center, and human resource standards.” Quenzer similarly highlighted both the financial value of network affiliation—Boys & Girls Clubs of America gives the Fresno County club about 8 percent of its revenue—and the value of training and programs.

Discussion Questions

- Under what conditions does affiliation with a national network provide value to a rural nonprofit?

- How should national networks structure their rural activities to meet the unique needs of their affiliates in these locales?

It is worth noting that, according to our analysis of their revenue mix, rural Boys & Girls Clubs look a lot like their urban counterparts. In comparison, rural youth development organizations that are not affiliated with national networks do not resemble their urban counterparts and receive far less funding from individual, corporate, or philanthropic donors. This data may indicate that for successful rural nonprofits, the national network may help to eliminate the disparities between urban and rural organizations via the supports discussed above.

Despite the apparent potential benefits of national network affiliation, this is not the answer for every rural nonprofit. For starters, not all feedback on the union between national networks and rural nonprofits was positive.

- Anecdotally, we heard that national networks have faced challenges building and sustaining rural programs.

- In our work with NIYLP, we assessed the rural work of a selected group of networks and found that affiliate feedback on network support was mixed.[15]

What’s more, for the nonprofits where there aren’t obvious partnerships with national networks available, many may succeed by creating community-based organizations that have a distinctive character. So, while a national network affiliation may be a good idea for rural nonprofits to consider, we need to see how unaffiliated nonprofits have succeeded and whether there are methods by which the benefits of a national network can be attained without a formal structure.

For rural nonprofits, closing the funding gap requires exceptional relationship building, lots of hustle, and good fortune.

We identified and interviewed six unaffiliated organizations that have successfully grown their organizations. When we asked their leaders to describe how they managed to secure the funding that supports relatively large rural nonprofits, common themes for successful growth emerged. Though the themes may be obvious, their execution is not. The leaders of these nonprofits have taken initiative to position their organizations well.

Theme#1: Focus on building strategic relationships and networks

All the leaders we spoke to had developed strategic relationships and networks. They uniformly spend a large proportion of their time networking—and they are good at it. These leaders recognize the obvious: If you want to attract resources to a rural community, you’ve got to go to the sources of funding. They’ll never find you!

Discussion Question

- Given the importance of relationship development outside of their home base, what are the risks of being absent from the day-to-day program work?

Mac Hall of NIYLP spends close to half his time away from NIYLP headquarters in Gallup, NM, working to advance positive development for Native youth more broadly—and along the way, building relationships with funders and friends from across the country. In 2002, via personal relationships, Hall learned of an opportunity to have his Project Venture certified as a “proven program” by the federal government, a designation that opened up new streams of public funding for NIYLP. He also has sustained long-running relationships within the New Mexico state government and with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, even during periods when short-term funding opportunities were limited.

Hall's longstanding personal relationship with Nicole Gallant (whom he met while she was at the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation and who later joined Atlantic Philanthropies) helped NIYLP connect to Atlantic Philanthropies. In 2007, Gallant supported the inclusion of NIYLP in a grant Atlantic had made to the Bridgespan Group that provided business planning support to a portfolio of nonprofits. She also facilitated a leadership coaching arrangement focused on organizational development. This business plan formed the platform for a 2008 grant from the foundation to support NIYLP's growth.

Jerry Cousins, executive director (ED) of the Human Response Network (HRN) in Northern California’s Trinity County (five hours north of San Francisco), considers networking a core asset. To strengthen his organization, which provides a wide range of programs for children, family, and youth, Cousins has created the capacity within HRN to support relationship building far from home. “HRN has developed interfaces with so many government officials and foundations [and is] very purposeful in getting out and being engaged in Sacramento.” Cousins has made a concerted effort to develop a well-trained staff that enables HRN to commit senior staff time to cultivating the network far afield while maintaining a consistent level of high-quality service at home.

Other EDs we spoke with shared the sentiments of Hall and Cousins. They all travel a lot and cultivate key relationships in their state and county governments and with foundations. They mine these relationships for opportunities to connect into new networks and for intelligence on new grant programs or legislation that might support appropriations for rural communities. Organizations without these connections face a complex funding world that is difficult to navigate and can result in many dead-ends that waste preciously scarce leadership time.

Theme #2: Be strategic about investing in grant opportunities

With strong connections, nonprofit leaders can become better positioned to learn about, assess, and pursue grant opportunities. As mentioned above, there is a wide array of grants that an organization might pursue. The question is, which grants are the best bets in terms of potential pay-off versus cost of pursuit? Too many nonprofits follow the “spray and pray” approach of writing as many grants as they can and praying that enough will come through to meet budget.

Obviously, the relationship building described in Theme #1 helps nonprofits gain the intelligence they need to decide which grants to pursue. In addition, small and rural nonprofits benefit from investing deeply and differentially in priority grant relationships. These are most frequently with state and county governments, which control most of the resources available for rural communities. But large foundation relationships also can pay off if there is a strong alignment. The rural nonprofits we spoke with invest deeply in grants that may further key relationships (even small ones) and minimize investment in small or one-off grants with small long-term payoff. They also are intentional about their decisions to avoid “off-strategy” grants to fill short-term revenue gaps, though they will pursue these grants to weather tough years.

The National Indian Youth Leadership Project has long pursued a strategy of focusing its grant writing on key relationships, whether the grant is large or small. For example, the level of funding NIYLP has received from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation has varied over time due to adjustments in the foundation’s program priorities. Still, NIYLP consistently invests in grants from Kellogg to maintain the relationship and cultivate longer-term opportunities. Similarly, NIYLP works actively on grants from the State of New Mexico, a critical long-term funder, and has pursued a range of grants that keep NIYLP relevant to the state’s needs. The National Indian Youth Leadership Project does its best to avoid working on small, one-off grants with foundations and government agencies that aren’t a good long-term fit.

Discussion Question

- How should nonprofit executive directors manage the risk of putting too many eggs in a few funding relationships vs. spreading their limited time too broadly over small sources?

Antioch University’s Center of Native Education (CNE), an intermediary organization that provides grants and technical support to Native educators to launch schools and programs that help Native people succeed academically, has been highly focused in its pursuit of grant opportunities. In 2002, Antioch University leveraged its track record of successfully working with tribal communities to establish reservation-based undergraduate and graduate degree programs to win a position among 13 partner organizations chosen by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for its Early College High School Initiative.[16] As a partner organization, Antioch’s Center opened the door to long-term grant relationships with the Gates and Kellogg foundations to develop early college high schools serving Native American and other underserved students. Since 2002, CNE has deepened its relationship with Gates and Kellogg, and has added grants from the Lumina Foundation.

The Human Response Network’s Cousins shared that early on, he was not selective about the grants he pursued because he was focused on growing the organization. However, when he recognized that “the nonprofits that were successful knew what they could do and do well, and built a reputation on it,” he became more strategic in which grants he pursued. “Many nonprofits pursue grants that require them to hire and train new staff to provide specific programs to fulfill the requirements of the grant,” said Cousins. “Often times, when the grant ends, they have to let people go.” The Human Response Network has selected a core set of programs, and it targets grants that align with its core. In addition, because HRN realizes that funding for specific programs areas often changes when state and local policymakers change, HRN has “made a concerted effort to cross-train staff” to be able to provide a variety of services. This helps the organization preserve continuity across program areas and among the staff even as sources of funding change.

Theme #3: Tailor program design to meet the unique needs of rural communities

While relationship building and strategic choices regarding fund development activities are important themes, an organization’s internal efforts to structure program design to meet the unique needs of rural communities is also vital. Effective program design is not only cost effective, but it also creates two funding opportunities. Namely, effective program design:

- Allows rural nonprofits to meet tight per capita funding formulas that might make urban nonprofits more appealing to funders; and

- Creates a unique value proposition for funders interested in innovative ways to serve rural communities.

Discussion Questions

- What opportunities are there to rethink program design to get more bang for the buck and mitigate cost challenges in rural communities?

In our work with NIYLP, we jointly wrestled with the challenge of serving a dispersed population of youth, many of whom live in remote areas on reservation lands. Further, each school that NIYLP served had relatively few students available for participation in the program. The economic implications were dire, as it was very costly to dedicate a staff member to an after-school group of four to five children. In rethinking elements of the program, NIYLP leaders decided to partner more closely with schools to serve whole classes in a more structured curriculum rather than an after-school format. They also decided to shift more intensive programming to weekends and holiday periods where they could run longer sessions, which would better amortize staff costs and transportation expenses. This dovetailed well with NIYLP’s core program goals of engaging youth deeply and created opportunities for outdoor adventures, such as group hikes.

For funders, the revised NIYLP approach was an attractive proposition, as it allowed funding at levels that were more aligned with its benchmarks, which were urban youth programs. Once NIYLP has the new program up and running, it will achieve similar costs per youth as an urban after-school program.

The National Dance Institute of New Mexico (NDI-NM) faced a similar situation as NIYLP. In considering how to move beyond its Santa Fe base, it faced the challenge that, aside from a satellite location in Albuquerque, it could not replicate its Santa Fe program model including its beautiful dance studios and large-scale program with the Santa Fe school district. Instead of limiting its efforts to Albuquerque or looking outside the state, NDI-NM developed an innovative rural model that proved to be highly effective and attracted significant public (from the state government) and philanthropic support. Its model entailed the development of a dance curriculum for schools to implement with the support of a mobile team of dance instructors to work with the students and provide training to the teachers. The rural program now serves over 74 rural schools at a manageable cost.

Important Work Ahead

The rural funding gap is real and points to significant challenges for both rural nonprofits and private foundations that care about tackling poverty. There are no silver bullets for rural nonprofit. Nevertheless, the themes put forth in this paper and, where appropriate, partnerships with national networks, present food for thought on how to expand the resources available for work with disadvantaged youth and families in rural communities.

While this article has focused on nonprofits, it is important to note that private foundations can and do play valuable roles in supporting rural nonprofits. We encourage additional efforts and innovation on the part of foundations (see sidebar below for brief discussion).

Conveners, such as the Council on Foundations, have created forums for dialogue on rural philanthropy. We encourage further dialogue, particularly among nonprofits, foundations, and public funders, on how to close the funding gap and strengthen rural nonprofit capacity. We also encourage comments on this article and further discussion at ~. To address the persistent poverty in rural America, the nonprofit sector must achieve its full potential. There is important work ahead.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Atlantic Philanthropies, which provided a grant that funded this research. Atlantic’s Nicole Gallant provided valuable support for the work and input into a draft of the document. We also wish to thank the organizations we spoke with during the research. In particular, our gratitude goes to the National Indian Youth Leadership Project, which provided the core case study for the work, and especially Executive Director McClellan Hall, who was a wonderful client. Finally, we wish to thank Christine Tran and Alli Myatt of the Bridgespan Group for their research work.

Sources Used for This Article

[1] Rachael Swierzewiski, “Rural Philanthropy Building Dialogue From Within.” National Committee for Responsible Philanthropy, August 2007.

[2] “Rural areas see funding gap,” Philanthropy Journal, August 2007.

[3] “Federal Investment in Rural America Falls Behind,” W.K. Kellogg Foundation, July 2004. Community resources federal spending category includes spending for business assistance, community facilities, community and regional development, environmental protection, housing, Native American programs, and transportation. Human resources category includes spending for elementary and secondary education, food and nutrition, health services, social services, training, and employment. National functions category includes spending for criminal justice and law enforcement, energy, higher education and research, and all other programs excluding insurance.

[4] James Richardson and Jonathan London, “Strategies and Lessons for Reducing Persistent Rural Poverty: A Social-Justice Approach to Fund Rural Community Transformation,” Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, Vol. 38, No. 1, Spring 2007.

[5] “Rural Income, Poverty, and Welfare: Rural Poverty,” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, November 2004

[6] U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates. http://www.census.gov/popest/national/national.html (accessed August 3, 2009).

[7] Charles Fluharty, “Challenges for innovation in rural and regional policymaking in the USA,” Rural Policy Research Policy Institute, 2005.

[8] "Rural Income, Poverty, and Welfare," United States Department of Agriculture, November 2004.

[9] "Poverty in Rural America," Housing Assistance Council, June 2006.

[10] "Rural Income, Poverty, and Welfare," U.S. Department of Agriculture, November 2004.

[11] The U.S. Economic Research Service defines persistent poverty as counties experiencing levels of poverty of 20 percent or higher for at least the last 30 years as measured by the 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 decennial censuses.

[12] Daniel Lichter and Kenneth Johnson, “The Changing Spatial Concentration of America’s Rural Poor Population,” National Poverty Center Working Paper Series, September 2006.

[13] Ibid

[14] "Breaking the Cycle of Poverty," Professional Association of Georgia Educators, May 2005.

[15] Bridgespan case team analysis (network names withheld to protect confidentiality).

[16] The Early College High School Initiative enables high school students to simultaneously earn both a high school diploma and an Associate's degree or two years of college credit toward a Bachelor's degree. The initiative is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Ford Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and Lumina Foundation for Education.

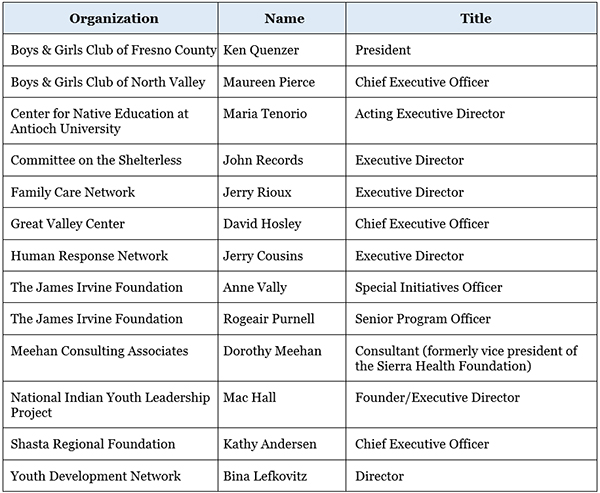

Appendix A: Interviewees

Interview subjects for the paper "Nonprofits in Rural America: Overcoming the Resource Gap."

Appendix B: Bibliography

“Breaking the Cycle of Poverty,” Professional Association of Georgia Educators, May 2005.

“Federal Investment in Rural America Falls Behind,” W.K. Kellogg Foundation, July 2004.

“Poverty in Rural America,” Housing Assistance Council, June 2006.

“Rural areas see funding gap,” Philanthropy Journal, August 2007.

“Rural Income, Poverty, and Welfare: Rural Poverty,” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, November 2004.

“Status of Education in Rural America,” National Center for Education Statistics, July 2007.

Suzanne Coffman, “Nonprofits’ Three Greatest Challenges,” GuideStar, April 2005.

Jennifer Day and Eric Newburger, “The Big Payoff: Educational Attainment and Synthetic Estimates of Work-Life Earnings,” US Census Current Population Reports, July 2002.

Charles Fluharty, “Challenges for Innovation in Rural and Regional Policymaking in the USA,” Rural Policy Research Policy Institute, 2005.

Patsy Klaus, “Crime and the Nation’s Households, 2004,” Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, April 2006.

Daniel Lichter and Kenneth Johnson, “The Changing Spatial Concentration of America’s Rural Poor Population,” National Poverty Center Working Paper Series, September 2006.

William O’Hare and Kenneth Johnson, “Child Poverty in Rural America,” Population Reference Bureau Reports on America, March 2004.

James Richardson and Jonathan London, “Strategies and Lessons for Reducing Persistent Rural Poverty: A Social-Justice Approach to Fund Rural Community Transformation,” Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, Vol. 38, No. 1, Spring, 2007.

Lester Salamon and Stephanie Geller, “Nonprofit Fiscal Trends and Challenges,” Johns Hopkins University Listening Post Project, 2007.

Debra Strong et al, “Rural Research Needs and Data Sources for Selected Human Services Topics,” Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., October, 2005.

Rachael Swierzewiski, “Rural Philanthropy Building Dialogue From Within.” National Committee for Responsible Philanthropy, August 2007.

Appendix C: Research Approach

Note on research methods

For this study, we focused specifically on youth-serving nonprofits in California and New Mexico—two states with enough rural and urban nonprofit organizations to represent the nation. Using the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) classifications to define “youth-serving,” we were able to draw from the National Center of Charitable Statistics (NCCS) database of Form 990 returns to create a sample of more than 850 organizations. We divided these organizations by “urban” and “rural” locales, ending up with 547 urban and 305 rural organizations.

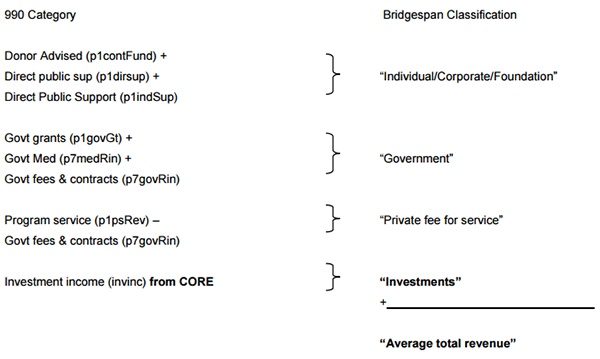

We then used the Form 990 data to map how many of the organizations fell into five revenue bands: 1) less than $0.5 million; 2) $0.5 to $1 million; 3) $1 to $3 million; 4) $3 to $5 million; and 5) $greater than $5 million. This enabled us to identify the number of large nonprofits in urban versus rural areas. To understand the relationship between funding sources and organization size, we categorized funding into four main categories: 1) individuals, corporations, and foundations; 2) government; 3) private fee-for-service; and 4) investments. When we aggregated the revenue from these four sources, we could compare funding patterns for urban and rural nonprofits and highlight key differences.

Furthermore, relying on NTEE codes, we broke the larger sample different youth-serving organization types, which allowed us to compare the funding patterns of nonprofits affiliated with national networks with those that operate as unaffiliated organizations.

From our initial pool, we identified more than 100 rural and urban youth-serving organizations, which we contacted with a request for nonprofit-specific annual and financial reports so we could understand their different funding sources in greater detail. Given a response rate of less than 10 percent, we are able to make only directional inferences about differences in individual, corporate, and foundation giving.

Finally, we leveraged the Form 990 analysis to identify a group of rural youth-serving nonprofits that had over $1 million in annual revenues. We specifically chose those organizations because we were interested in learning how they overcame the funding challenges and grew large. We were able to interview seven of the organizations. From these interviews, as well as interviews with a few private foundations, community foundations, and intermediaries (see Appendix A for the interview list) and a review of existing research (see Appendix B for the bibliography), we identified a set of strategies that rural nonprofits have successfully employed to overcome funding challenges. We also identified a set of targeted recommendations for private foundations that are interested in supporting rural nonprofits.

Note on urban/rural definitions

For this study, we defined the following California and New Mexico Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) and Consolidated MSAs (CSAs) as “urban.” All zip codes falling outside of these urbanized areas were considered “rural.”

While the MSA/CSAs in California are significantly larger in population size than those in New Mexico, given that New Mexico has a significantly smaller population and less population density than California, we defined New Mexico’s two major cities as “urban,” because they are centers of activity in the state.

California

CSAs and MSAs with populations greater than two million, and which are major centers of activity are considered urban:

Los Angeles – Long Beach – Santa Ana MSA (& Orange County) – 13 million

San Francisco – Oakland – Fremont MSA – 4.1million

San Diego – Carlsbad – San Marcos MSA – 2.9 million

Sacramento – Arden – Arcade – Roseville MSA – 2.1 million

New Mexico

The two primary CSA/MSAs that are centers of activity are urban:

Albuquerque, NM MSA – 817,000

Santa Fe, NM MSA – 142,000

Note on definition of “youth-serving organization”

For this study, we have defined the following National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities Core Codes (NTEE-CC) as “youth-serving organizations” because of their explicit focus on youth (anyone under the age of 18). We have intentionally excluded “Education” (public sector) and “Recreation & Sports” (overlaps/includes adult-serving organizations). Please refer to later pages in this document for additional detail.

Categorized as “Youth-Serving Organizations”

O20 Youth Centers

O21,22,23 Boys & Girls Clubs

O30 Adult & Child Matching Programs (Mentoring)

O40 Scouting Organizations (Scouting)

O50 Youth Development Programs (Youth development)

I21 Youth Violence Prevention (Violence prevention)

P40 Family Services (Family services)

Categorized as “Other”

O01-O19 Other Youth Development

O99 Youth Development N.E.C. (not elsewhere classified)

K30 Food programs

Definitions for codes:

O20 – Youth Centers: Organizations that provide supervised recreational and social activities for children and youth of all ages and backgrounds, but particularly for disadvantaged youth, through youth-oriented clubs or centers with the objective of building character and developing leadership and social skills among participants. Excludes Boys & Girls Clubs.

O21,22,23 – Boys & Girls Clubs: Organizations specifically designated as Boys & Girls Clubs that provide a wide range of supervised activities and delinquency prevention services for children and youth of all ages and backgrounds, but particularly for disadvantaged youth, with the objective of building character and developing leadership and social skills among participants.

O30 – Adult & Child Matching Programs : Programs, also known as adult/child mentoring programs, that provide male or female adult companionship, guidance and/or role models for young men or women. Includes Big Brothers and Big Sisters.

O40 – Scouting: Programs that provide opportunities for children and youth to develop individual and group initiative and responsibility, self-reliance, courage, personal fitness, discipline, and other desirable qualities of character through participation in a wide range of organized recreational, educational, and civic activities under the leadership of qualified adult volunteers. Code for troop-type organizations not specifically designated as Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts of the U.S.A, or Camp Fire.

O50 – Youth Development Programs: Programs that provide opportunities for children and youth to participate in recreational, cultural, social, and civic activities through membership in clubs and other youth groups with a special focus on helping youngsters develop their potential and grow into healthy, educated, responsible, and productive adults.

I21 – Youth Violence Prevention: Organizations that offer a variety of activities for youth who have demonstrated or are at risk for behavior which is likely to be unlawful or to involve them in the juvenile justice system. Also included are community councils, coalitions, and other groups whose primary purpose is to prevent delinquency. Keywords: Gang Related; Juvenile Delinquency Prevention; SADD; Students Against Destructive Decisions; Students Against Drunk Driving; Youth Crime Prevention.

P40 – Family Services: Organizations that provide a wide variety of social services that are designed to support healthy family development, improve the family’s ability to resolve problems, and prevent the need for unnecessary placement of children in settings outside the home. Code for organizations that provide comprehensive family support services.

O01 - Alliances & Advocacy: Organizations whose activities focus on influencing public policy within the Youth Development major group area. Includes a variety of activities from public education and influencing public opinion to lobbying national and state legislatures.

O02 - Management & Technical Assistance: Consultation, training, and other forms of management assistance services to nonprofit groups within the Youth Development major group area.

O03 - Professional Societies & Associations: Learned societies, professional councils, and other organizations that bring together individuals or organizations with a common professional or vocational interest within the Youth Development major group area.

O05 - Research Institutes & Public Policy Analysis: Organizations whose primary purpose is to conduct research and/or public policy analysis within the Youth Development major group area.

O11 - Single Organization Support: Organizations existing as a fund-raising entity for a single institution within the Youth Development major group area.

O12 - Fund Raising & Fund Distribution: Organizations that raise and distribute funds for multiple organizations within the Youth Development major group area.

O19 - Support N.E.C.: Organizations that provide all forms of support except for financial assistance or fund raising for other organizations within the Youth Development major group area.

O99 - Youth Development N.E.C.: Organizations that clearly provide youth development services where the major purpose is unclear enough that a more specific code cannot be accurately assigned.

K30 - Food Programs: Organizations that provide access to free or low-cost food products to children, seniors, or indigents by distributing groceries, providing meals, providing facilities for storing food or making available land on which people can grow their own produce. Use this code for organizations that provide a wide range of food services or those that offer food-related services not specified below.

Note on IRS Form 990 analysis

Since National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS) data is self-reported by nonprofits, there are often inaccuracies and inconsistencies within and across 990 forms. NCCS’ ability to reduce the number of errors, beyond identifying a relatively small number of egregious errors, is limited. Given the size of the data sets, it is impossible as a practical matter to locate the majority of the errors without contacting thousands of individual organizations directly.

That said, according to an NCCS study on the reliability of Core Files and other 990 data:

- Error rates are acceptable for most research purposes; and

- Total revenue and its component sources (e.g., investment income, public support), as well as total expense and balance sheet items from the rich text formats (the Core files) can be used for the vast majority of observations.

To calculate the funding model for each nonprofit, we used the following formula:

Please note: “Average total revenue” includes only revenue raised in a single fiscal year. This number does NOT include assets that rollover from previous years of income.