Developing a funding strategy that leads to financial sustainability is vital to any nonprofit’s ability to make a difference in the world. Yet, too often, reacting to fundraising opportunities or following conventional wisdom (e.g., “diversification is good”) substitutes for thoughtful planning around a funding strategy. Many nonprofit leaders have been asked by board members why their organization isn’t hosting a gala, pursuing a grant, or launching a viral social media campaign like other organizations. Aren’t you leaving money on the table by not going after more types of funding?

Maybe not. According to The Bridgespan Group’s research and experience in the United States (see “A New Look at How Nonprofits Get Really Big”), 1 it turns out that nonprofits often benefit from concentrating on just one or two revenue categories (such as government, philanthropy, corporations, or earned income) and building dedicated capabilities to match.

More on Funding Strategy

This article is for nonprofit leaders—from smaller to larger organizations—who are developing (or revisiting) their funding strategy for the long term. While our prior research 2 has centered on organizations with annual revenues of $10 million or more, we have seen many smaller nonprofits benefit from this combination of focus and dedicated capabilities. To be sure, it’s also true that smaller organizations may still want to be somewhat opportunistic while taking time to plan for the capabilities they’ll need for a sustainable funding strategy.

A funding strategy is, of course, inseparable from an organization’s overall strategy, operations, and ambitions. With that in mind, the process of developing your organization’s funding strategy should focus on three main questions:

- What is your funding model today and what has it taken to raise that money?

- What might be the optimal one or two revenue categories—a “major” current or potential category and a “minor” source (important secondary)—for your organization?

- What capabilities do you need to successfully raise money from those revenue categories?

It may take a few months to hit upon a funding strategy—or it can take longer, depending on how much change and depth of engagement with board members, funders, and other stakeholders the strategy calls for. Whether it is part of a broader strategic plan or a stand-alone process, it will require a good deal of senior leaders’ time and a staff member to manage planning activities. Some nonprofits will do this work on their own, and others may find some outside support helpful.

It’s an investment well worth making. Instead of seeing every funding lead as a good lead, you can focus on those that align well with your strategy. Instead of wondering where and how to invest in development capabilities, you can see a road map for the capabilities you need to develop. Whether you are seeking to grow or mainly to sustain your current size, a well-defined funding strategy will better position your organization to attract the dollars needed to achieve your aspirations for impact in the world.

1. What Is Your Funding Model Today and What Has It Taken to Raise That Money?

You likely know a good deal about how you raise money today. But that knowledge can become outdated quickly, be scattered across different parts of the organization, or be based on perceived wisdom rather than on data. With a funding strategy, the way forward starts with a look back, focusing on three areas: revenue mix, funder motivations, and the capabilities needed to raise that revenue. This knowledge will pave the way for a strategy that builds on strengths and navigates or addresses weaknesses.

Revenue mix. Your annual report or presentation to the board may show a pie chart with the annual revenue by category. But it is also important to understand trends and to group or disaggregate the data in a way that lets you get under the hood of your fundraising machine and get a better sense of what has really been going on. Some questions to ponder are:

- What does the revenue mix over the past five years look like? Looking back that far (if your organization is old enough) can spotlight some longer-term trends that may be harder to see one year at a time. For example, individual giving may be your biggest revenue category, but has its share of total revenue been growing or declining over time?

- Is there another way to slice the revenue data? For example, many nonprofits have a separate category for events. But it can also be helpful to understand how much event revenue is coming from individuals or corporations. In our own research, we have used these overall categories: government, service fees or program revenue, corporations, foundations, high-net-worth individuals, small individual gifts, and investment income.

- Within a category, where does most of the money come from? For example, perhaps there have been trends in the size of gifts over the past five years or in who has been giving. Is most of the funding in a revenue category coming from one or two key relationships or from many?

- How flexible is your funding? How much is tied to specific programs? Will the revenue continue even if a program goes away or changes substantially?

- How long are donors or other types of funders sticking with you? For individual, corporate, or foundation donors, or even customers, how long do funding relationships tend to last and how did they first become engaged with the organization?

By answering these questions, you are in a better position to think about what you may want your future funding model to look like.

Funder motivation. “Know your customer” is a commercial mindset that can be applied to all donor types. Reach out to your donors or other funders! Development professionals know full well how useful it is to understand the extent to which funders are motivated by the track record of the organizations they support, the population or issues the organizations focus on, or personal relationships with the organizations’ leaders. Likewise, it can be helpful to learn more about how your organization fits within the larger set of organizations the donor is supporting and whether their funding interests and patterns might be changing over time. That information is just as valuable for planning as it is for fundraising.

Over the years, as Bridgespan has conducted research into funding models, we have observed patterns in what motivates funders. For example, many government agencies fund education and human service nonprofits, as such causes are linked to their roles in serving constituents. Many philanthropists fund early-stage medical research, as such efforts are often not commercially viable and likely would not proceed without philanthropic support. We refer to these patterns between a funder’s motivations and an organization’s work as a “natural match.”

Asking questions about funder motivation and match can help you better understand what differentiates your organization in the eyes of funders—and evaluate whether you’ll need to alter that positioning to attract the level of funding you’re targeting. (For more, see the sidebar “Understanding and Addressing Funder Motivations.”)

Fundraising assets and capabilities. What has it taken to raise your current revenue? It’s important to assess as candidly as possible what your organization is good at doing, where it is less skilled or experienced, and what kind of staff, tools, or other assets it might need to most effectively pursue a specific fundraising strategy. This doesn’t mean that your organization should try to be good at many different things. But an organization needs to be clear about the baseline it’s starting from.

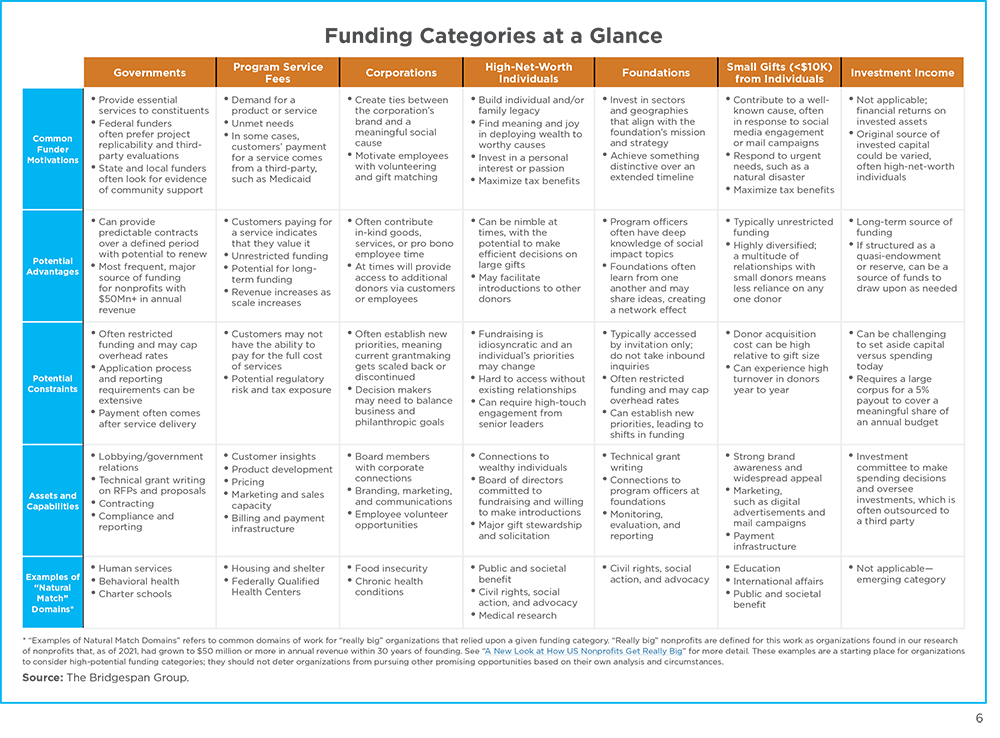

The assets and capabilities required to effectively pursue a revenue category can vary a lot depending on the category. The following chart lists some of the most important capabilities associated with each revenue category. Consider it a starting point in asking critical questions about what your organization is good at and where it may need to improve as it pursues an effective and sustainable revenue mix. (Click on the image below to view a PDF copy of the table.)

The first and most important question is: What are you good at? The best fundraising strategies build on strengths and address weaknesses as needed. For example, an organization that raises a lot of its revenue from government usually gets good at responding to government funding announcements, delivering the program elements required by the funder, tracking compliance with government contracts, and advocating for new or expanded funding streams. An organization that attracts large donations from affluent individuals, on the other hand, typically has an executive director and likely a board that knows or is able to meet such donors.

The first and most important question is: What are you good at? The best fundraising strategies build on strengths and address weaknesses as needed. For example, an organization that raises a lot of its revenue from government usually gets good at responding to government funding announcements, delivering the program elements required by the funder, tracking compliance with government contracts, and advocating for new or expanded funding streams. An organization that attracts large donations from affluent individuals, on the other hand, typically has an executive director and likely a board that knows or is able to meet such donors.

If your organization has been at least somewhat successful in raising the revenue it needs, what strengths have you developed within the organization? Does your executive director do a lot of fundraising? Do you have a strong grants team? Does your annual gala or other event bring in good revenue and help build relationships with donors and other stakeholders? Do leadership and other staff feel good about their fundraising work or is it draining and overwhelming? Understand and celebrate your successes, and be honest—but not overly critical—about capabilities or assets that may be lacking.

Whether the analysis of revenue mix, funder motivation, and fundraising capabilities brings surprises or mainly confirmation, it can help your organization understand and align on where it is today—and go on to tackle key questions about its future funding strategy.

2. What Might Be the Optimal One or Two Revenue Categories for Your Organization?

Based on a good understanding of where your organization is today, it’s time to develop, test, and refine a hypothesis about the optimal revenue categories going forward.

Developing a hypothesis about the target revenue mix. Whether your organization already has ideas about the path forward or begins the process with a blank slate, your funding hypothesis will need to consider the organization’s current revenue mix, the extent to which its program model would allow it to appeal successfully to the relevant funders, and whether it has—or could develop—the capabilities required to access that funding.

Here is an example of a nonprofit that has been innovative in tapping into a new revenue source, understanding funder motivation, and assessing changes in the external context.

Originally focused on people living with HIV/AIDS and funded primarily through donations and government support, Community Servings expanded over the years to provide medically tailored meals to individuals and families with a range of chronic or critical illnesses both in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In the 2010s, the organization saw an opportunity to add earned revenue to its mix. “The Affordable Care Act changed the payment incentives; there was some new funding around making sure people stay healthy,” says David Waters, the organization’s CEO. At that time, Community Servings thought that the new legislation might make revenue from health care payers a natural match with the work it was doing.

But health care payers initially met the idea with skepticism, so Community Servings set out to understand the motivations of these potential funders. “We went to them and asked what it would take for them to fund us. Their main question was about return on investment,” Waters explains. How would the benefit of providing these meals in terms of healthier clients compare to the cost of providing them?

Understanding that it had to make the business case for funding, Community Servings partnered with a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital to analyze state-level insurance claims data. They found significant cost savings and reductions in hospitalizations among Community Servings’ program participants. With this evidence, Community Servings secured insurers as major payers, shifting its revenue mix so that fee-for-service is now its second-largest revenue category after philanthropic support.

The target revenue mix is one that gets as close as possible to being sustainable at the desired pace of growth. It should not overly restrict the work that your organization is committed to doing, and it should provide a good longer-term return on investment over the cost of raising that revenue.

In thinking about funding strategy, it’s usually important to focus on one or two main categories of revenue—your major and your minor. Sometimes funds may become available from outside these one or two categories of focus (like an unexpected bequest or other large gift). It’s fine to react to such opportunities but beware of spending a lot of effort on them. We know a lot of nonprofits that have gotten very good at raising revenue from one or two categories. We know very few that are good at raising revenue from several categories.

Let’s consider two examples of developing a funding hypothesis.

Partners in School Innovation supports people at all levels of the K–12 public education system to work for educational equity. In the early 2010s, the organization relied mainly on philanthropy, though about 30 percent of its revenue came from earned income. In looking at the market for the kind of services it offered, its leadership came to believe it could significantly boost the amount of earned income from school districts. “If our product is strong, then districts should be willing to pay for it,” explains CEO Derek Mitchell. In other words, it believed its program model could allow it to build a market among school districts.

Another example comes from Maternity Care Coalition (MCC), a Philadelphia-based nonprofit focused on improving the health and well-being of parenting families, mothers, and young children ages birth to 3. Historically, MCC relied on government grants for 60 to 70 percent of its revenue, with the rest coming from foundations and several other sources. The organization was seeking to grow in scale and impact. When Marianne Fray became CEO in 2018, she initially focused on diversifying into other funding categories. “I was uncomfortable with that mix, and I thought we might be too dependent on the government. I wanted to balance a portfolio of revenue.”

Both organizations’ initial hypotheses included making significant changes in their revenue mixes; their funding strategy processes led them to different conclusions, as we describe below. Other organizations may believe that the path forward will involve mainly continuity, with perhaps some tweaks around the edges. This is a common and often wise hypothesis, as long as it is based on a solid understanding of your current revenue mix and funding capabilities.

Testing and refining the hypothesis. An especially useful way to see whether a hypothesis about a fundraising strategy makes sense is to look at what peer organizations are doing. If organizations similar to yours have successfully built the capabilities to raise significant revenue from the one or two funding categories you want to focus on, it increases the likelihood that your hypothesis is feasible. This process of studying and learning from peers (see “Finding Your Funding Strategy: Benchmarking 101”) can help you refine the initial funding hypothesis—or maybe even develop an entirely new one.

Peer organizations may be similar in issue focus, organization type, or revenue size. Or they may be somewhat bigger—representing the size your organization aspires to be rather than what it is today. Key questions in peer research include what the peer organizations’ overall revenue mix is, what changes in revenue have occurred over the past few years, and what the specific funding sources are, as well as how peers raise that revenue. These can be investigated with desk research—looking at organizations’ websites, annual reports, and press releases, along with information from their Form 990 submissions to the Internal Revenue Service (easily accessed through the ProPublica Nonprofit Explorer).

Ideally, desk research will be supplemented by at least a few conversations with the staff or board of peer organizations. It can be difficult to figure out from annual reports or other data exactly how an organization is raising its money, so these conversations can help you learn more about another organization’s fundraising, the kind of efforts it has undertaken, and the capabilities it has developed. If it’s challenging to have candid conversations with organizations that feel like direct competitors, look at peers in a different geography or a different sector. Usually, the most productive conversations will be two-way—sharing your data and experiences as you learn about those of your peers.

Another angle on peer research is to look at funders. For example, a youth-serving organization that seeks to expand and deepen its violence-prevention work might want to know what chance it might have of getting federal or state violence-prevention funding. By identifying potential government revenue streams and seeing who gets funded through those streams (which is hard to find for some government funders, much easier for others), it can get a sense of whether and which peer organizations have been able to access those funding streams—and if there’s any realistic chance of tapping into any of those streams themself. And it can often be valuable to talk to funders to get a better understanding of the kind of organizations they fund and why—and to test out your hypothesis with them.

It may also be important to ask whether there have been changes in the external environment that might support or hinder the pursuit of your funding hypothesis. Are new funding streams becoming available or are current ones drying up? Is the environment around your program model changing in a way that might make it easier—or harder—to pursue a particular funding strategy? For example, as mentioned in the sidebar above, one of the main motivators for Community Servings to explore fee-for-service as an important revenue source for its meals program was the recent passage of the Affordable Care Act changing payment incentives in health care.

As your organization tests your funding hypothesis with stakeholders, conducts peer research, and considers any changes in the external environment, you will better understand your options, begin to distinguish the possible from the unlikely, and learn more about the capabilities needed to pursue or increase a particular revenue category. This testing may confirm or significantly alter your initial hypothesis about the best revenue mix going forward. And it may alert you to opportunities and challenges on the road ahead.

MCC had initially worried that it was too dependent on government revenue. But as its leaders thought more about its fundraising and programmatic strengths, it returned to the central role played by government revenue. “We rely on government funding. It’s very stable,” explains Karen Pollack, executive vice president of programs and operations. “We work closely with various government agencies around shared public health goals, so government funding is a natural extension of this partnership. In addition, we have a team that works to supplement these funds through foundation grants, corporate support, and individual giving.”

Rather than going off in a completely new direction, it doubled down on what it did best. Its funding strategy coalesced around broadening and diversifying its revenue sources within the government category it was already good at. Pollack explains, “Our work has a broad span from children’s health to maternal health to early childhood education. So we are able to make sound arguments for creative funding solutions and projects to address the wide array of diverse issues our families face.” For example, MCC won a grant from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency to support violence-prevention work within an existing program.

3. What Capabilities Do You Need to Successfully Raise Money from Those Revenue Categories?

Mapping the capabilities needed and what it will take to develop them. At this stage of the process, your organization should be clearer about what it will take to pursue a particular revenue category, what it is already good at, and where it will need to further develop—or even create from scratch—the needed capabilities. As it pursues the work of building capabilities, it will learn even more:

- What specific capabilities will it take to execute the new strategy? These may not all be apparent at the outset—so will require both advance planning and a fair amount of adaptability along the way.

- Which of these is it already good at and which will it need to build or strengthen?

- How much will it cost? And what is the opportunity cost of building new capabilities? Building capabilities may require hiring new staff, building new systems, or buying new technology. And it could take several years for added revenue to come online to pay for these investments.

Recall the example of Partners in School Innovation, which decided to significantly increase the share of revenue from earned income from school districts while maintaining a smaller but still significant share from philanthropy. “In the past, we never really had any business expertise,” explains Mitchell. “The earned revenue agreements we had with school districts came mainly through word of mouth, and business development was mostly just me.” So, the organization identified key elements it needed to get good at—writing proposals, developing materials, and managing the business side of the operation. It hired someone to be in charge of business development and put in a financial and invoice system. And over a period of years, it supported its program managers in driving business development themselves.

Managing change, adapting as you go along. A critical question may be how much your organization will need to change to pursue its funding strategy.

Sometimes, fundraising will be the job mainly of the development department and the executive director. However, other funding strategies may require much more organizational buy-in and support. Depending on the particular strategy being pursued, this may include some or all of those engaged in the hypothesis development and testing process—the staff, board, and external stakeholders.

Program staff became an essential element in MCC’s successful effort to grow and diversify its government funding streams. “Grants aren’t just the responsibility of the development team,” says MCC’s Pollack. “We have 14 people across the organization who work on grants. We ensure that program staff are part of the grant development process. The engagement of program staff ensures we are centering client needs as well as addressing staff capacity.”

An implementation plan will need to be created to support the building of needed capabilities, and that plan will likely need to be adapted as the strategy encounters real-world experience. It can take 18 to 24 months—or longer—for a fundraising strategy to pay off or for you to understand that it may not work. It’s helpful to think about pilots or indicators that the funding strategy might be gaining traction along the way: For government grants, working with a consultant grant writer on a few credible submissions (even if they are not funded right off the bat) before hiring one or more full-time grant writers could be a useful pilot. For foundations or large individual givers, outreach from board members or the number of good conversations held (even if those conversations do not immediately result in checks being written) could serve as an indicator. For individual giving, a digital fundraising campaign would allow you to use analytics to quickly see what is working and what is not.

The process may involve a lot of trial and error. “Initially, we weren’t completely sure what kind of talent we needed,” says Mitchell of Partners in School Innovation. How much of the work could be done by people the organization already had? Or would they need new people? “Ultimately, it was about making a transformation in the organization. There was a lot of change management.”

“A rule of thumb is keep coming back to your core mission.”

We have seen that there are a few essential elements in developing an effective and sustainable revenue mix: understanding your organization’s current revenue mix and fundraising capabilities, developing and testing a hypothesis about what revenue mix would best support your organization, and building the capabilities needed to pursue that revenue mix.

Of course, you’ll need to revisit your strategy and implementation plan as you go along. Things go wrong, and circumstances change. Partners in School Innovation successfully developed its program revenue from school districts so that by the late 2010s it accounted for 60 percent of its revenue mix, with philanthropy playing a secondary but still vital role. Then the pandemic hit, and school districts had to cut back. But the organization was still good at engaging philanthropy, which stepped up to ensure that the organization could continue its work.

“A rule of thumb is keep coming back to your core mission,” says Mitchell. “We focus on program revenue and philanthropic support. We can find other funders, but if we stray too far from them, we find ourselves looking at working in places that aren’t a good fit for us or what we’re trying to accomplish.”

By focusing and building the capabilities to do one or two things really well, your organization will have a better chance of finding and pursuing a strategy that will position it to attract the dollars needed to achieve its aspirations for impact in the world.

Footnotes:

[1] Ali Kelley, Darren Isom, Bradley Seeman, Julia Silverman, Analia Cuevas-Ferreras, and Katrina Frei-Herrmann, “A New Look at How Nonprofits Get Really Big,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 20, 2024.

[2] William Foster and Matt Hochstetler, "Funding: Patterns and Guideposts in the Nonprofit Sector," The Bridgespan Group, September 1, 2023.

Footnotes:

[1] Ali Kelley, Darren Isom, Bradley Seeman, Julia Silverman, Analia Cuevas-Ferreras, and Katrina Frei-Herrmann, “A New Look at How Nonprofits Get Really Big,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 20, 2024.

[2] William Foster and Matt Hochstetler, "Funding: Patterns and Guideposts in the Nonprofit Sector," The Bridgespan Group, September 1, 2023.