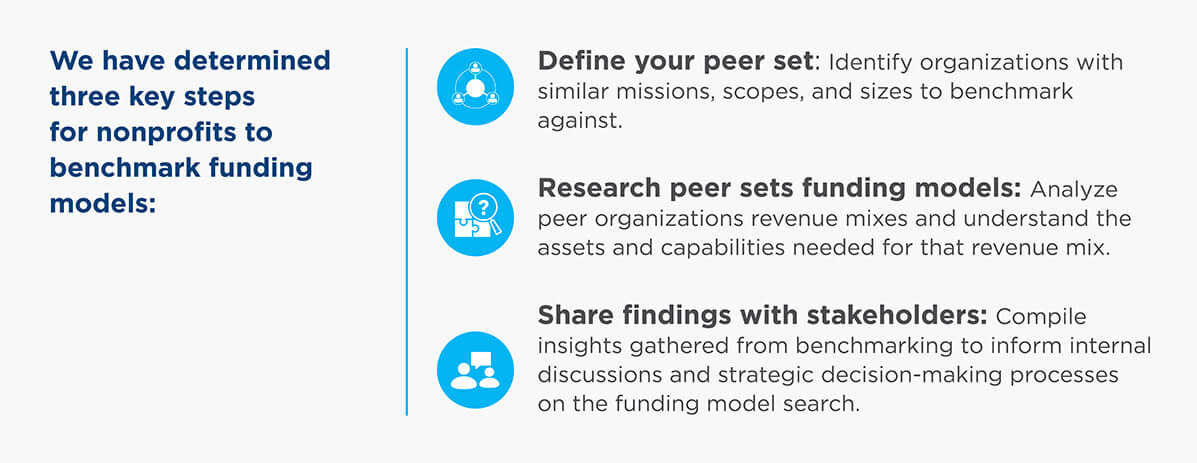

For nonprofits seeking an effective funding model, a helpful first step is benchmarking against similar organizations. This process combines quantitative assessments, such as comparing revenue mixes among peers, as well as qualitative, like identifying best practices and emerging trends. Benchmarking can provide a holistic view of the funding landscape, including clear paths to long-term sustainability.

Depending on a nonprofit’s specific needs and resources, the depth of benchmarking can vary from a basic review of a handful of similar organizations to a more comprehensive analysis involving a larger peer set. Please note that the process outlined here utilizes databases and tools relevant to US nonprofits; in other parts of the world, organizations may need to supplement their research with qualitative research methods, such as interviews, to account for regional differences and nuances.

These suggestions are based on Bridgespan’s experience and research but should be taken as reference points rather than precise steps, and we would expect nonprofits to tailor their own approaches.

Define Your Peer Set

Defining your peer group is a crucial step for nonprofits seeking to understand their optimal revenue mix. This entails identifying roughly five to 15 organizations that closely resemble yours in mission, size, and geographic scope.

Your peer organizations ideally share similar goals and operate in comparable areas. However, including slightly larger organizations can offer insights into scaling opportunities. In addition, including those with different focuses or in different regions can spark potential new opportunities. For instance, a middle school literacy program in Cincinnati, Ohio, might include similar programs in Cleveland or Columbus in its peer set.

More on Funding Strategy

Organizations likely already have a clear idea of who some of their peers are. Identifying a complete set is often as simple as reviewing organizations you already know, considering overlaps in program areas nearby, or using connections and networks within your field. It may be helpful to scan recent conference attendees, coalition members, or board member connections to look for existing relationships within your peer group.

To identify additional peers, consider using nonprofit databases like ProPublica’s free Nonprofit Explorer search tool or Candid’s subscription-based Guidestar Pro Plus database. Both platforms offer filters for revenue size, location, subject area, type of tax entity, and other criteria that can help you add to your peer set.

Going back to the example above, the Cincinnati literacy program might refine its search in ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer tool using filters such as revenue amount and subject area to find organizations with similar financial profiles (the program’s revenue plus 20 percent annually) and serving similar issue areas. This process might validate known peer-set organizations while surfacing others in, say, Cleveland.

Curating a peer group aligned by mission and size, whether through preexisting connections or online resources, creates a starting point for determining which organizations’ revenue mixes to research.

Research Peer Set’s Funding Models

Now that you’ve established your peer group, it’s time to dig into what type of revenue these organizations bring in. This involves checking out public financial sources and ideally talking directly with peer organizations to get more detail. Before we dive into the data, let’s break down the different ways nonprofits typically get their funding.

Understand the funding sources

First, let’s identify the main funding sources. These usually include things like grants, donations from individuals, support from companies, and money earned from services or products. From Bridgespan’s research, here are examples that track to different revenue sources:

But keep in mind, it’s not always clear-cut. It can be tricky to pinpoint exactly where an organization’s money comes from just by searching online. However, understanding these broad funding categories can direct your analysis and help guide decision making.

Research publicly available financials for peer organizations

Once you understand the inputs for various funding sources, the next step is to dive into financial research. We recommend creating a spreadsheet that tracks the funding sources of your peer organizations. Each organization typically requires 15 to 30 minutes of research, so a starter list of six to eight peers will take less than a half day’s work.

To start, organize your list by each organization’s US Employer Identification Number, which serves as their legal tax registration number, to allow easier tracking and referencing. There are several avenues for accessing their financial data, including audited financials, annual reports, and Form 990 filings.

Audited financials are often the most reliable source, readily available on platforms like ProPublica Nonprofit Explorer and Guidestar Pro Plus, or on the nonprofit’s own website. Annual reports can also provide valuable insights, especially if the audited financial statements and Form 990s list contributions. Form 990 filings, while mandatory for all organizations, may not identify specific funding sources but still offer a glimpse into revenue breakdown, especially for program services and government.

Once you’ve gathered the financial data, you can record the revenue each organization receives from different funding sources. Consider estimating your degree of confidence in your findings: flag uncertainties that need further clarification from the organizations themselves. During this process, look for recurring funders that appear within the peer sets. For example, the Cincinnati-based literacy program might find that many of its peers received funding from fee-for-service revenue.

When benchmarking funding models, nonprofits can analyze both their peers’ most recent year’s revenue mix and financial data from previous years. We have found that looking back up to five years can reveal changes in revenue concentration. This historical analysis is valuable, yet time-intensive, so nonprofits may choose to focus on a select few organizations of particular interest or alignment.

Sharpen research by speaking directly with peer organizations

As you may notice, it is often difficult to pin down the source of each revenue stream with just online sleuthing. This is where it can be helpful to talk to the organizations themselves to understand their revenue mixes and their related assets and capabilities. This step is not mandatory for benchmarking funding models, but we encourage it so you can fill in the gaps.

When selecting organizations to engage with, target a diverse range of peers, including those similar to yours but perhaps in different geographic locations or with slightly different program focuses. Funding can often feel competitive, so you may have more candid conversations by speaking to organizations slightly different than yours. They also offer more opportunities for cross-learning.

Contacting organizations through your own personal networks is also valuable. The middle school literacy organization may choose to speak to other middle school literacy programs in Louisville, Cleveland, Columbus, and a couple after-school tutoring programs in Cincinnati.

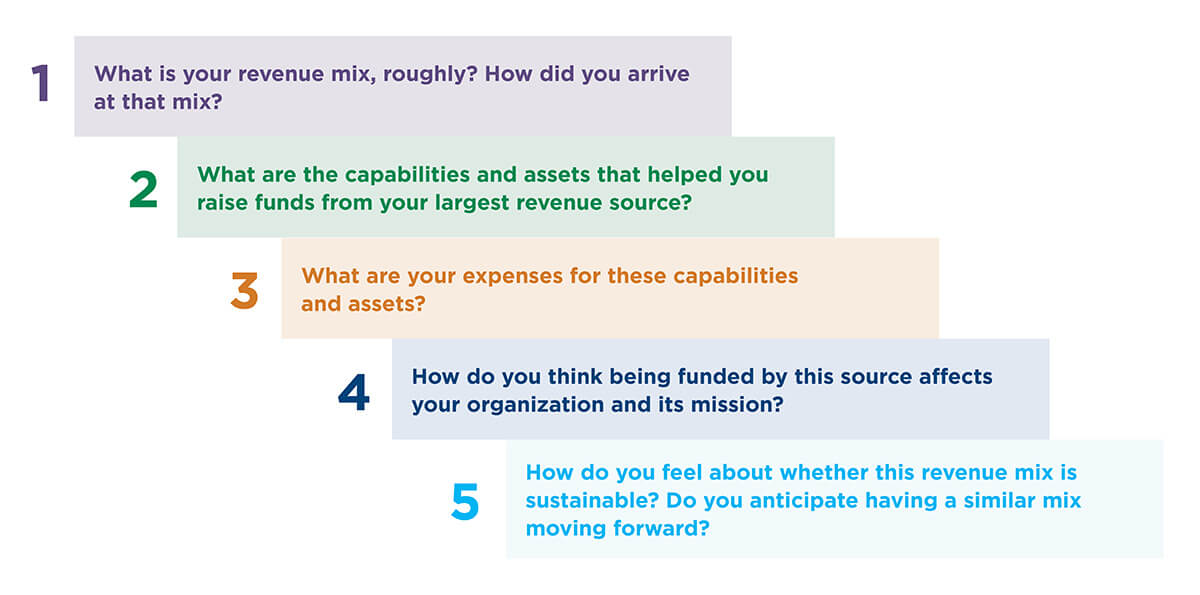

When crafting outreach, it can be helpful to emphasize that you are willing to share what has worked and not worked for your own organization. Once the interviews are scheduled, be prepared to ask—and answer— questions about revenue mix, fundraising strategies, resource requirements, and the impact of funding sources on the peer organization’s mission and sustainability. Some sample questions, which you should tailor to match what your organization is curious about, include:

These conversations may include the executive director, chief financial officer, chief strategy officer, or other top executives. Through a few 45- to 60-minute calls, nonprofits can gain insights that inform how they develop their own funding strategies and growth trajectories.

Explore funding model viability

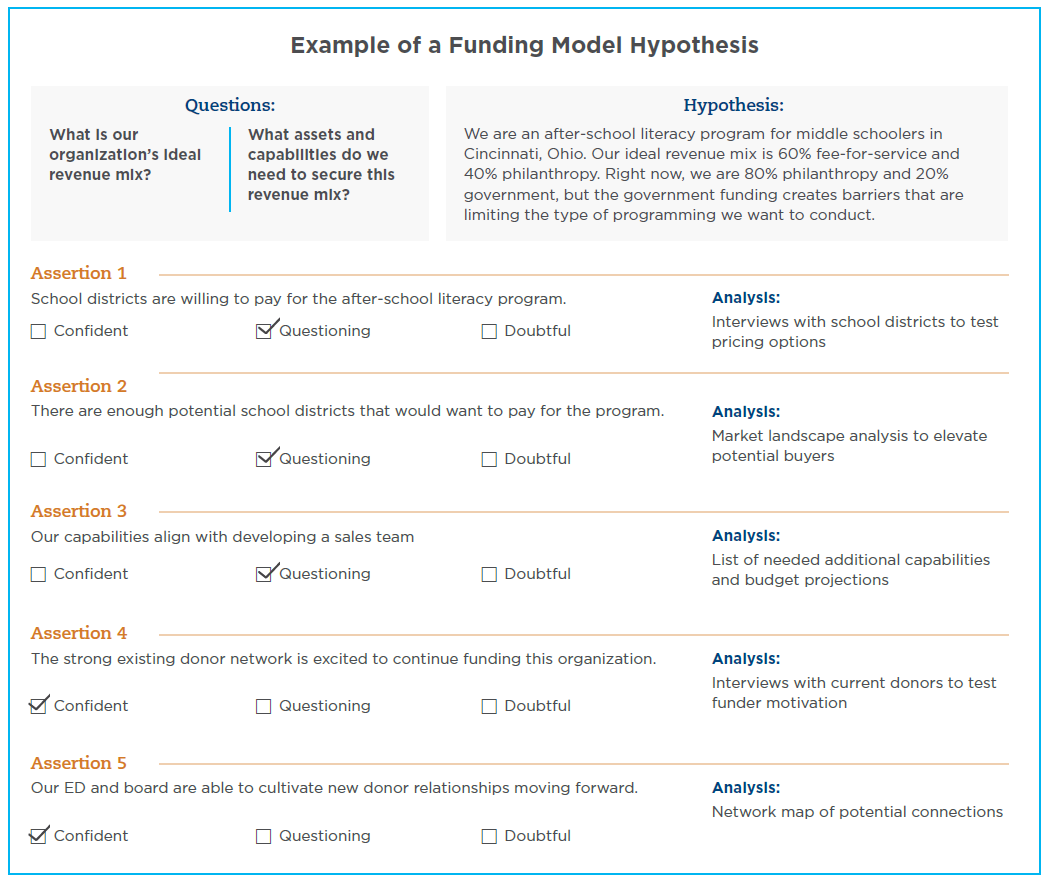

Once you’ve compiled and analyzed the research on peer organizations’ revenue mixes, it’s time to translate these insights into actionable strategies for your organization’s own funding model. First, this involves forming a hypothesis based on your understanding of your peer organizations, their revenue mixes, and the pathways taken to achieve them. A hypothesis would sketch out the potential of your revenue mix and the capabilities it would require. (See an example in the figure below.)

Ideally, you would also assess the viability of the hypothesis although it may not always be necessary or possible. For example, having seen the importance of fee-for-service revenue for its peer group, the Cincinnati literacy program might see a bright future in building capabilities to pursue fee-for-service funding. It could validate that hypothesis by comparing its activities with school districts’ program criteria. On the other hand, those who hypothesize that institutional philanthropy could play a large role might examine funders’ websites or utilize databases like Candid’s Foundation Directory to look for overlap in funders’ portfolios. If so, it would indicate that their missions align with funders’ priorities.

Some organizations take another extra step and engage directly with potential funders to gather more information and insights. It may be helpful if someone slightly removed from the organization—such as a board member, outside consultant, elected official, or community member—initiates the conversation to encourage candor. By engaging directly, a nonprofit can learn more about the funder’s priorities, criteria, and past experiences with similar organizations. This firsthand interaction can also validate the proposed funding model and help refine the organization’s approach to securing funding.

Share findings with stakeholders

After validating the hypothesis, take time to consider how best to share these findings with key internal stakeholders—including nonprofit leadership, development teams, strategy personnel, and the board—who are vital to shaping and guiding the organization’s funding model.

Visualizations are helpful in communicating research findings. For example, bar charts showcasing peer revenue mixes can illustrate the concentration of funding sources within each organization, providing valuable insights into potential funding trends. A five-year retrospective of your own organization’s revenue mix and growth conveys how your funding mix has evolved over time.

Additionally, we recommend distilling key messages and themes gathered from interviews with peer organizations. This highlights the capabilities and assets required for securing different funding sources. Incorporating quotes from these interviews adds depth and credibility to the presented findings.

By engaging in this benchmarking process, nonprofits can develop a hypothesis and discuss what their ideal funding models should be, considering their landscapes and peers. After benchmarking and internal discussions occur, nonprofits can take action to build out implementation plans and chart the path toward a sustainable funding strategy.