Measurement isn’t just a yardstick for success—it’s also a tool for learning and improvement. In our work with nonprofits, we’ve seen how those who measure to learn often find that they’re able to have more impact, adapt their programs to changing circumstances faster and more effectively, and make better resource allocation decisions.

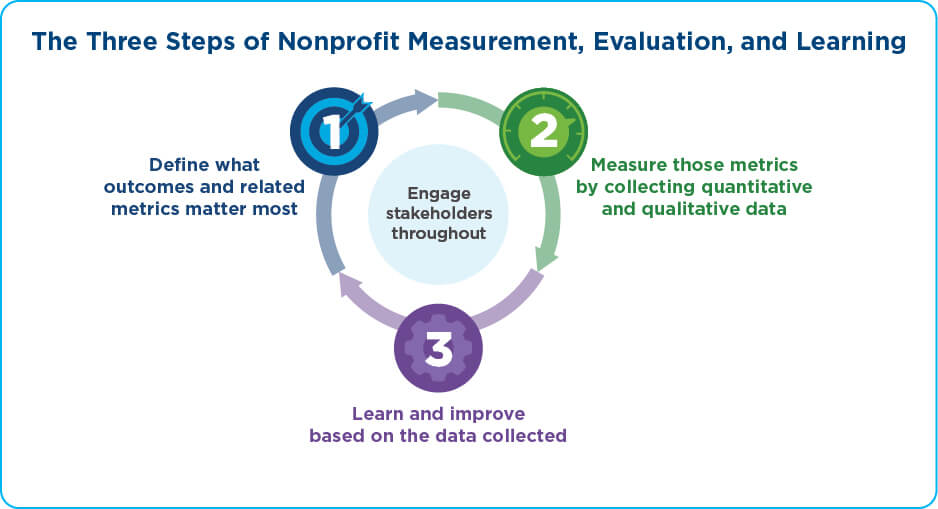

The basic steps of nonprofit measurement and evaluation are straightforward:

- Define what outcomes and related metrics matter most, based on the organization’s theory of change.

- Measure the metrics by gathering quantitative and qualitative data.

- Learn and improve based on the data you collect.

In addition, organizations typically engage stakeholders—e.g., constituents, front-line staff, board, and donors—throughout the process, from incorporating input on what outcomes matter to reporting back. This can be critical to making measurement approaches more equitable. (For more on incorporating equity, see “How Nonprofits Can Incorporate Equity into Their Measurement, Evaluation, and Learning” on Bridgespan.org.)

(See “Nonprofit Measurement, Evaluation, and Learning at a Glance” for a more detailed view.)

In the real world, nonprofit leaders and their teams can face real challenges to doing measurement well. In working with nonprofits and NGOs in Africa, Asia, and the United States and conducting interviews for this article, including speaking with some organizations that we have worked with in the past, The Bridgespan Group team was keenly aware that organizations—especially smaller nonprofits—have limited resources for measurement. We have called this a “practical” guide because it offers advice on using the resources you have—or can reasonably add—to address these challenges and effectively measure, learn, and improve.

Define What Outcomes and Related Metrics Matter Most

Tips

- Start with what is most important to learn

- Less is more—select the vital few outcomes core to your theory of change

- Determine what you can measure in the short, medium, and long term

One of the most common places we see organizations get stuck is in the process of selecting outcomes and metrics to track. The work of nonprofits and NGOs is increasingly complex, making it hard to identify a short list of outcomes that are both meaningful (i.e., they capture the full spirit of an organization’s work) and measurable (i.e., they are feasible to track).

Start with what is most important to learn

Beginning with your organization’s most important goals and how you will achieve them (sometimes called your intended impact and theory of change) can help focus your measurement and learning strategy on what matters most for your impact.

Intended Impact and Theory of Change

See “What Are Intended Impact and Theory of Change and How Can Nonprofits Use Them?” for more explanation of these terms and how to clarify them. Also, without getting too technical, a “logic model” illustrates how a program performs activities that result in your intended impact. Program resources, activity measures, and impact are the inputs, outputs, and outcomes we refer to later.“We were founded in 2017 and within the first couple of years we created a formal theory of change,” explains Viridiana Carrizales, co-founder and CEO of ImmSchools, which partners with school districts in four states to create more welcoming and safe schools to meet the needs of K–12 immigrant students and their families, many of whom are undocumented, and educators.

Like many nonprofits, ImmSchools has struggled to define outcomes that are “just right”—ambitious and meaningful signs of progress within a reasonable timeframe and focused on what’s most vital.

The organization mainly works with schools and districts that have many undocumented students. Its focus is knowledge building and professional development for teachers and school staff, school policies, and support for students and families. There’s plenty of research on the challenges faced by undocumented students, and the field has generally consolidated around key outcomes like attendance and academic performance. But ImmSchools was developing new programming for this historically underserved population.

“It’s great to get to define something that hasn’t been done before, to have a new framework,” Carrizales says. “It’s also really challenging. So, in the first few years, the most important thing we wanted to know or prove was that the main elements of our theory of change were true.”

Questions to guide a leadership team in defining outcomes and related metrics

Getting to metrics takes many conversations that start from your strategy and lead to an outcomes framework that connects inputs, outputs, and outcomes to your intended impact and theory of change. Here are a few questions to help guide those conversations:

- What are your organization’s goals and how will you achieve them (sometimes called intended impact and theory of change)?

- Consider also engaging stakeholders (constituents, front-line staff, board, and donors) to create a learning agenda to identify, prioritize, and address critical open questions and knowledge gaps, such as:

- What aspects of your theory of change and/or logic model have the least evidence (whether internally or externally)?

- What strategic decisions tied to your impact can’t you make over the next 3-5 years because you don’t have the data/evidence?

- Consider also engaging stakeholders (constituents, front-line staff, board, and donors) to create a learning agenda to identify, prioritize, and address critical open questions and knowledge gaps, such as:

- What inputs, outputs, and outcomes map to your intended impact and theory of change?

- What metrics or indicators will help you know that these inputs, outputs, and outcomes occurred?

See “How to Define What Outcomes and Related Metrics Matter Most” for more practical guidance and examples on how to map your intended impact and theory of change to an outcomes framework.)

Learning questions should come before metrics. Thinking those through in advance will help ensure that what is being measured is relevant to how the organization wants to improve.

“We’re such a data-driven organization. We sometimes go right to ‘what are our metrics?’” explains Kelleen Kaye, senior advisor for research strategy at Upstream USA, a nonprofit that works with health care organizations to make contraceptive care more affordable and accessible for millions of people around the United States. “But we need to formulate the questions first. What is it we want to learn? What can we learn? These aren’t just measurement questions, they’re strategy and organization questions.”

Upstream’s theory of change focuses on the vital role of health centers in contraceptive care. So what it most wants to learn is how and to what extent its work is helping health centers build capacity and change how they deliver services—and whether these changes are making care more affordable and accessible.

For organizations doing newer kinds of work—such as changing how health centers deliver contraceptive care, like Upstream, or working to make schools safer and more welcoming for immigrants, like ImmSchools—it may take more work to demonstrate whether their theory of change is sound and how they can show progress toward their intended impact. Organizations could be interested in other questions across their theory of change—such as questions about whether the program is having disparate impacts on different populations.

In addition, broadening the conversation beyond the organization’s senior leadership or its measurement specialists can make the process more inclusive. Front-line staff, clients, community members, and other stakeholders may have important insights about what is most important to measure, how to frame outcomes, and how the results might be used to increase the organization’s impact. For example, ImmSchools created an eight-person committee of students, parents, educators, and school leaders to advise on learning questions and evaluation results. And it pays its constituents for the time they spend on this work. “From day one, we met with students and families who helped us develop our theory of change and identify that sense of belonging in schools was an essential outcome to track,” Carrizales says.

Less is more—select the vital few outcomes core to your theory of change

“Less is more” sounds like an easy win but selecting the vital few outcomes to measure can be one of the most challenging aspects of nonprofit performance measurement.

Organizations often end up measuring more data than they need and don’t use it all to inform their work. But with time and experience, many reduce the number of outcomes they measure. “It’s easy to come up with a list of 50 measures,” says Laura Mills, senior director of quality and evaluation at A Place Called Home, which serves youth and their families in South Central Los Angeles. “But in practice, most nonprofits don’t have time for side quests when it comes to measuring their impact. If everything is important, nothing is important.”

Indeed, many of the organizations we interviewed for this article ended up collecting less and understanding more. “You can’t measure everything. What is possible and within our reach? What are the few things we can best measure?” says Dr. Lorena Tule-Romain, co-founder and COO of ImmSchools. “Start small!”

How do you determine what those vital few metrics are? It’s helpful to start by asking yourself: Will we learn anything actionable from it? How much burden does collecting the information impose on us and others? What decision can't we make because we are missing this information today? And it’s helpful to revisit those questions from time to time.

Of course, over time, you may also be tempted to expand the metrics you collect. Indeed, as an organization matures and builds its measurement capacity, there may be a good reason to broaden its range of measures, such as new programs or more holistic measures of its outcomes. As you consider new metrics, however, consider the return on investment of collecting each.

“It’s easy to come up with a list of 50 measures, but in practice, most nonprofits don’t have time for side quests when it comes to measuring their impact. If everything is important, nothing is important.”

“After a few years, we realized we were collecting data on too many outcomes,” explains Tule-Romain. ImmSchools scaled back the number of outcomes it tracked. “We now focus on three high-level outcomes that are most aligned to our organization’s impact goals: students’ sense of belonging, school culture, and our reach.”

Refining data already required by funders could further learning goals. Some organizations find their measurement strategies significantly affected by funder data collection requirements—and not all government or philanthropic funders subscribe to “less is more.” Fei Yue Community Services is a social service organization in Singapore that delivers a wide range of services like family services, early intervention for infants and children, mental health, eldercare services, and much more to a variety of populations. Most of its funding comes from the government, which requires data collection on standard measures.

“This is very helpful for the sector because if every organization uses the same measures, it’s easy to see what’s happening across organizations,” explains Helen Sim Keng Ling, who leads the organization’s Applied Research team. “But these standard measures aren’t always sufficient for our program improvement.” So in some cases, Fei Yue Community Services supplements those measures with a few additional questions—but only a few—to help them understand not only what is happening but also why.

Determine what you can measure in the short, medium, and long term

While outcomes that are attributable to the organization’s work are the focal point for most organizations, one challenge is that some of the most important outcomes may not occur for a long time or may be outside your direct control. What do you do in the meantime?

Sometimes, interim measures make sense. Upstream’s metrics are focused on practice change in health centers, which are ultimately tied to its goal of increasing access to equitable, patient-centered contraceptive care. Its measurement approach starts with what is most measurable, even if these are interim measures that don’t yet tell the full story. For example, are health care organizations providing a full range of services? But it is also trying to understand more about how these services are provided—such as whether any contraceptive services are provided during the patient visit. Getting this kind of data is harder, but sometimes possible when Upstream is able to draw from a health center’s electronic health record data.

The question of whether these changes are leading to more affordable and accessible contraceptive care is vital—but much harder to answer in the shorter term. The best practical strategy is sometimes to look at interim measures rather than at outcomes that have yet to be achieved or that will take a long time to come to fruition. In some fields, there may already be research that links certain short-term and measurable changes in attitudes and behaviors to longer-term outcomes like a reduction in teen pregnancy or youth violence or an increase in the rate of college completion. The metrics will likely be a mix of outputs and outcomes, lagging and leading, qualitative and quantitative, and roll-up. (For definitions of these terms, when to use these metrics, and examples of each, see “Leadership Team Dashboards: Priority Metrics and Examples” on Bridgespan.org.)

Remember that for organizations working in newer areas, patience may be needed. “Our program hasn’t been around long enough to manifest changes further along in our theory of change,” says Kelleen Kaye of Upstream. “We can’t tell a story that hasn’t unfolded yet.”

For efforts focused on policy, norms, and systems change, it’s okay to focus on outputs in the near term. Outputs such as research conducted, partnerships formed, or trainings or convenings held are meaningful progress indicators if an organization and its partners are to learn how the work is going—even if the indicators are only provisional and approximate.

Consider the example of India-based Arpan, whose goal is a “world free of child sexual abuse.” Arpan not only delivers direct prevention and healing services for children and adults but also engages in training and advocacy work to achieve its ambitious goal. The organization sets more measurable intermediate milestones for what it hopes to achieve. Bhuvaneswari Sunil, Arpan’s director of research, monitoring, and evaluation explains: “For example, we are working to integrate our curriculum in government programs. Short-term outcomes are things like meetings with the right policy makers, medium-term outcomes include the integration of our curriculum into a teacher training, and long-term outcomes are tied to successful program implementation.”

In addition, it is important for organizations working on policy or systems change to keep a watch on what is happening in the larger system in which they work—new opportunities, challenges, population-level changes—even if these are not necessarily attributable to their own work. They monitor these systems-level outcomes because their work, with many other actors, is contributing toward systems change, even if they don’t anticipate results until the much longer term. (For more on measurement strategies for organizations working on systems change, see “How Nonprofits and NGOs Can Measure Progress Toward Systems Change” on Bridgespan.org.)

Measure outcomes by gathering quantitative and qualitative data

Tips

- Right-size your data collection strategy

- Consider using data, tools, and other resources that already exist

- Digitize and standardize your tools whenever possible

Many leaders we talked to are working to collect the data they need without overburdening clients, partners, or staff. Nonprofit staff time is limited, as is that of constituents and partners.

Right-size your data collection strategy

While prioritizing a shorter list of outcomes will help to contain the time and resources required, it also helps to consider how you collect data on those outcomes. Perhaps sampling a representative set of participants, for example, will tell you just as much as reaching out to all participants.

There are good reasons to limit your data collection: reducing the resources needed to carry it out; minimizing the burden on clients, partners, and other constituents; and allowing leaders to focus on what’s important rather than burying them in a mountain of data.

Right-sizing data collection comes down to thinking about three things: the tools or approach to collect the data, the amount of data you collect, and the time you take to collect it.

"We were using lots of different data collection tools. Focus groups, school visits, surveys, and others. It wasn't necessarily all that well-connected to what we were trying to learn—and we were trying to do too much."

“We were using lots of different data collection tools,” says Carrizales of ImmSchools. “Focus groups, school visits, surveys, and others. It wasn’t necessarily all that well-connected to what we were trying to learn—and we were trying to do too much.” ImmSchools has since cut back to three main methods of assessment: documenting its reach, conducting surveys, and using a rubric or checklist related to a safe and welcoming school culture, with such metrics as educator preparedness and family engagement. With its data now more closely connected to its goals, it is better positioned to learn how its supports are improving outcomes for students and families.

Other reasons to right-size include data availability and quality. If a nonprofit or NGO works in settings with limited data, it faces a tradeoff: invest in collecting original data or rely on proxy data that may be incomplete but good enough. Of course, a focus on quality is essential. A nonprofit that works in settings with limited data could use proxy data, instead of investing in collecting original data, but only if that proxy data are good enough to learn from.

Quality can depend not only on the survey instrument but also on when and how it is administered. Mills from A Place Called Home cites the example of youth in their summer program being taken out of an especially fun activity to complete a survey—which could seriously compromise the results. “I want to be in the room seeing how a survey is being given. You want to know if the data collection is happening the way you think it’s happening.”

Do you need a formal evaluation study?

There is no single “gold standard” approach to evaluation. More formal evaluations, almost always conducted with an academic or other research partner, can take a variety of forms—from a full-scale randomized controlled trial to other types of quantitative or qualitative research. Evaluations can also be combined with cost data to better understand return on investment across programs or geographies.

A Place Called Home published an evaluation report on its logic model conducted with Gray Space Consulting in August 2023. The 15-month study assessed the impact of the organization’s programs on its members and organizational efficacy in terms of program inputs and activities. Study methods included document review, staff and members surveys, focus groups, and on-site observations of program activities. The report produced findings and recommendations in areas such as professional development, safe physical spaces, and data management.

This kind of evaluation study nevertheless takes substantial resources to produce, including time and money.

Laura Mills, senior director of quality and evaluation, describes the rationale behind the study. “First, it helped us create capacity to collect data linked to our logic model. Now we’re continuing to use those tools. Second, some people in leadership and on the board saw it as a way to prove what we were already doing well. Now we have something to show to people. And a third goal was to understand what’s not going well and what can we change. The biggest thing we found is that members want more choice and flexibility in the programming.

“That report started the ball rolling. We’ve done additional surveying since then, and we’re getting a good handle on the opportunities for improvement.”

Whether or not you need a formal evaluation study—and what type of study—depends on:

- What are your needs for rigor? For example, if there is existing evidence on your program (or a comparable one), you might not need an evaluation. Or if you have ambitions to significantly scale the program, funders and other partners may want a formal evaluation to validate impact first.

- How established is your program model? Regular performance measurement is more appropriate for a program that is still piloting activities and refining its model. In contrast, a formal evaluation is best suited for programs whose components are more firmly set.

- Does your organization have the bandwidth, expertise, or resources to do an evaluation? If you have the resources, a formal evaluation could help build an organization’s expertise. If it’s not worth prioritizing bandwidth, a third party can conduct one. Given the importance for program improvement, many nonprofits and NGOs include measurement costs in their program budgets to secure more resources for measurement.

To go deeper on evaluation, a few resources that may be helpful include:

- BetterEvaluation’s Advice for choosing methods and processes

- IDinsight’s Impact Measurement Guide

- Project Evident’s Next Generation Evidence

- The Evaluation Center at Western Michigan University’s Evaluation Checklist

Consider using data, tools, and other resources that already exist

Existing data, tools, and other resources can play an important role in your measurement approach—even if your programs are innovative or groundbreaking.

Tapping into existing data can be an important part of a measurement strategy. ImmSchools has focused on measuring the extent to which its work with schools and students increases safety and a sense of belonging. “But we’re hearing from our partners and funders that our work has to be more explicitly connected to academic outcomes,” says Carrizales. Now it is trying to use existing school data to better understand and communicate how safety and belonging might translate into improved attendance and academic achievement—metrics which are critical to schools and districts.

Fei Yue Community Services can tap into data collected by the government of Singapore on many of the issues it addresses. Though Fei Yue Community Services' Sim Keng Ling notes, “What’s missing from government data is the voice of stakeholders—so it’s important to hear from clients and others about their experiences.”

Likewise, validated or widely used measurement tools may give you more confidence in the data and provide comparisons with other organizations or the field. Mills explains, “Like many nonprofits working with young people, we focus on social-emotional learning. We initially spent a lot of time figuring out what we wanted to measure. But now we use Hello Insight—an existing tool. We didn’t have to create or validate our own survey—that saved a lot of work.” In addition, as the organization seeks to work more closely with school districts, using a standard measure for social-emotional learning provided important evidence of success.

Existing channels and touchpoints also make data collection more efficient. Data collection activities can be built into regular touchpoints like program sessions, meetings with clients, staff, or partner organizations, or ongoing outreach. Surveys and other data collection methods are sometimes most effective when combined with communication channels already in use. ImmSchools was already using WhatsApp to communicate with students and families, so it built its surveys into the platform they used every day.

Digitize and standardize your tools whenever possible

Upgrades to the tools or processes already in use can make the process easier. Sometimes, this means digitizing. For example, the availability of smartphones—while no panacea—can help reach constituents who are harder to connect with, lower costs, and improve response rates.

“We’re basically all digital now,” says Sim Keng Ling. This means clients can now fill out surveys on their own time and front-line staff can use built-in data features to do some kinds of analysis themselves. “And transcribing services not only save us time and money but also ensure we can incorporate client voice across the many dialects and languages our clients speak.”

While technology can be used to collect more and more data—a temptation generally to be avoided—it can also reduce the burden of data collection on staff and constituents. Upstream’s Kaye explains: “We used to conduct our patient survey in person, and it was burdensome for the clinic. It’s all now virtual—and much less burdensome for everybody.”

But upgrades need not be new or expensive. For example, Upstream added more structure to its surveys around what they ask and when they ask it. And they connect with clinics’ electronic health record systems when possible so they have comparative data across different partners. Standardization can make data both easier to collect and analyze.

Learn and Improve Based on the Data You Collect

Tips

- Build a dashboard to track the most important outcomes in one place

- Review data regularly and think about how you will act on it

- Share the right level of detail with key stakeholders so they can act accordingly

While there seems to be more data at nonprofit leaders’ fingertips than ever before, we hear teams are not always translating data-driven insights into action for the organization in terms of programs or strategy. Sometimes this is because data is too siloed within the organization and disconnected from key decisions, or because team members may not build in regular opportunities to analyze, reflect, and act on the data.

Build a dashboard to track the most important outcomes in one place

How to Build a Dashboard

“How to Build a Nonprofit Dashboard for Your Leadership Team” walks through how to build a dashboard and structure a review meeting, and offers templates to help get you started.

A performance dashboard tracks the vital few metrics an organization needs to measure and monitor, providing just enough data to know how things are going. It can help your leadership team focus on what matters most, assess progress in a timely way, and act on the information and follow up.

A dashboard should point leaders to the right information at the right time. Just like in a car, if the “check-engine light” comes on, leaders know they need to start addressing a problem. A nonprofit dashboard should include metrics—one or two per outcome—that provide just enough data to track progress toward its theory of change. If something signals red, it’s time for a deeper look.

“Your dashboard shouldn’t be a laundry list of all the outcomes,” says Sim Keng Ling of Fei Yue Community Services. Fei Yue Community Services runs multiple programs for several populations in Singapore, so it uses multiple dashboards tailored to specific groups within the organization like managers and front-line staff. “We sit down with staff to understand their most important business questions and tailor the metrics and data visualization to those questions.” It also helps to make clear which person or team is accountable for each outcome.

Additional Tools

Review data regularly and think about how you will act on it

The leadership team, managers, or other stakeholders should set a cadence—monthly, quarterly, or annually—to review the data that makes sense for them. It helps to schedule a meeting dedicated to this review so that other agenda items don’t take over.

For example, during Arpan’s quarterly organization-wide meeting with all departments, staff discuss what each team can do better based on the last quarter’s data. “These meetings break down silos and strengthen the teams’ understanding of how their work connects to others. Looking at the data together translates into dialogue, troubleshooting, and innovation,” says Pooja Taparia, founder and CEO.

ImmSchools noticed that once the new federal student aid (known as FAFSA®) forms came out, parents and students in surveys described problems in the system. Seeing this flashing red light—which had real implications for the futures of the immigrant students and families they worked with—the organization adapted its programming to provide more support around the forms. It even went further, reaching out to Department of Education officials about how the new FAFSA forms were affecting undocumented families.

“People have to be willing to change what they’re going to do based on data—to hear what the data is telling you and make adjustments,” says Mills of A Place Called Home. The organization’s leadership regularly reviews its dashboard data during quarterly leadership meetings. And it makes changes based on what it’s seeing—including changes in program offerings and schedules. “Though it can be hard to make a lot of changes all at once. When people are more hesitant to hear information, you may need data to make the case.”

Share the right level of detail with key stakeholders so they can act accordingly

The results of measurement and evaluation can be vital to the organization’s work and impact—and therefore to a range of stakeholders. Sharing the right level of detail with key stakeholders can help them understand what the organization has learned and allow them to participate in supporting and strengthening it. “We tailor the data we share to each audience, sharing the different metrics that resonate the most with our board, donors, or partners,” explains Lisa Leroy, Upstream’s vice president of monitoring, evaluation, and learning.

Constituents and front-line staff: This might include clients and participants, community members, organizational partners, or staff. Some of them may have been involved in the data collection itself, so engaging them thoughtfully helps to close the loop. Several of the organizations we interviewed described not only sharing findings but also engaging people about what the findings might mean. For example, one organization shared school system study data with the headmaster and teachers to ask them how they thought their approach to retention could improve based on the data. And Mills of A Place Called Home says, “In the fall we’ll report back to our youth leadership team on how we use the advice they gave us last spring. This is a way to involve them more in our measurement and evaluation work.”

Board: Dropping a lot of data on a board isn’t necessarily much help to anyone. Anchor on sharing with the board only data that speaks most clearly to strategic priorities, as opposed to all the data. To the extent that an organization’s board is focused on larger questions of strategy and finance, it’s important for them to see and understand the data and insights that are most relevant to those questions. For some boards, this may mean getting out of the weeds of day-to-day data and focusing on the bigger picture. For others, it may mean helping them make the connection between longer-term outcomes that may not be measurable yet and the useful intermediate metrics you do have.

Donors: An organization’s current or potential donors can be an important audience for measurement results. Though there is no one way to engage donors, best practices include: creating a compelling case for the organization’s work (ideally anchored in a theory of change); making it tangible by describing what the work looks like and connecting aspirations to tangible milestones; and educating and sharing data, insights, and the rationale for approaches being taken or any shifts as a result of what the organization is learning.

Advice for getting started—for nonprofits without a data team

The practical advice described in this article applies to organizations with various levels of resources and capacity. For leaders without a data team, though, it can be helpful to think through where to start.

For example, ImmSchools does not yet have a full-time staff person devoted to measurement, evaluation, and learning, though it hopes to add a position. In the meantime, the organization has benefitted from a partnership with Rutgers University that has given it access to much-needed expertise in measurement and learning.

Below is some advice on where to start, using your existing capacity:

- Outline a back-of-the-envelope theory of change and ask yourself: What do you know/not know about how you are making an impact? What are you measuring/not measuring tied to how you are making an impact?

- Then, broaden the conversation. Show what you have to a few front-line staff and clients and ask the same questions. Now, prioritize what outcomes to measure based on what you don’t know.

- Start small and early. Go through the cycle once (e.g., with one program), then iterate. To get a better sense of outcomes over time and why they might have changed, you might: survey clients for their experience and track implementation before, during, and after your program, or conduct structured interviews of a few clients to build case studies.

- Leverage a teammate’s data interest or partner with a university until you can hire dedicated staff. For example, you might pick a program person who is comfortable with numbers and communicating insights and dedicate 30 percent of that person’s time to measurement. Get peer support by connecting to other nonprofits or communities of practice.

- Keep your tools simple and actionable. You don’t need to hire a software developer to build a beautiful dashboard. Start with tracking your three metrics in a spreadsheet and review the metrics during a leadership call.

- Close the loop with constituents and show and tell to build culture. Seeing is believing. Once you’ve gone through the cycle, share with your staff, clients, board, and funders one or two “proof points” of what you learned and how you’re changing. Get their perspectives on what you might tackle next.

Build a Culture of Measuring to Learn

“Many of the challenges organizations face when doing this work are not technical. That’s why focusing on people and a culture of learning is essential,” explains Claire Robertson-Kraft, founder and executive director of ImpactED, a center for social impact at the University of Pennsylvania that works with mission-driven organizations in the Philadelphia region. This work won’t stick without focusing on culture.

Building culture starts with leadership. No matter how much data they collect, or evaluation reports they produce, if an organization’s executive director and board do not see measurement as about strategy more than compliance and use data to make decisions, it’s a signal that measurement and learning aren’t a high priority.

Leadership also communicates with staff about why it matters and encourages a culture of sharing both good and bad results. “We’ve seen busy front-line program staff push back against data collection for many reasons. They get tired of doing this work in addition to their jobs delivering quality programs,” says Arpan’s Taparia. So, Arpan not only provides trainings but also shares with staff the “why” behind the data collection to build buy-in and get better data to analyze. That includes tying data collection to its theory of change and sharing examples of how it improved program delivery and strengthened Arpan’s ability to fundraise (and scale its impact further).

And finally, leadership engages stakeholders at every stage of the process, emphasizing the perspectives of those closest to the work. “Our data-driven culture stems less from data than from our decision to ensure that the voices of our students and families informed this work from day one,” says Carrizales of ImmSchools. “Because at the end of the day, their success is our impact.”