Achieving large-scale, enduring social change in a community, region, nation, or globally often involves more than serving individuals. It requires changing systems—that is, targeting root causes to shift the underlying structures that contribute to the issue and often exacerbate inequities. Think about addressing basic incomes and food deserts and not just expanding food pantries to tackle food insecurity in a community.

Across a range of issues, there are organizations for which systems change has long been at the core of their work. Today, we are also seeing more direct-service nonprofits expanding their work to pursue various forms of systems change. But how do these nonprofit leaders, accustomed to measuring direct service work, know if they’re making progress against their systems change goals? Many organizations are wrestling with this measurement question.

Measurement approaches that work well in evaluating direct services may not tell the full story when it comes to systems change. After all, counting the number of students graduating from college or increases in household assets after a person starts a mobile bank account doesn’t tell you whether you’ve moved the needle on economic mobility. Measuring and learning from systems change work requires a different mindset.

Why is that? Systems change work is fluid, often nonlinear, and long term. It is not always characterized by forward progress—sometimes ground will simply be held, or even lost. Since this work involves a dynamic system, it is hard to model what might happen in six months, let alone six years.

Yet measuring progress toward systems change goals, though messy, is possible. The key elements are to:

- Develop a guiding star based on a clear map of the system and deep engagement with the individuals and communities most impacted

- Identify measurable milestones and progress indicators

- Monitor the ecosystem

- Adapt your strategy and methods along the way

Let’s consider how one NGO (nongovernmental organization) is using this measurement and learning framework to scale its work and deepen its impact.

Develop a guiding star based on a clear map of the system and deep engagement with the individuals and communities most impacted

Lend A Hand India works to prepare youth for employment and entrepreneurship opportunities. It does this by integrating vocational education (“skills education”) with mainstream education for students age 14-18. In its direct-service work, the organization engages over 10,000 students in more than 150 schools across India.

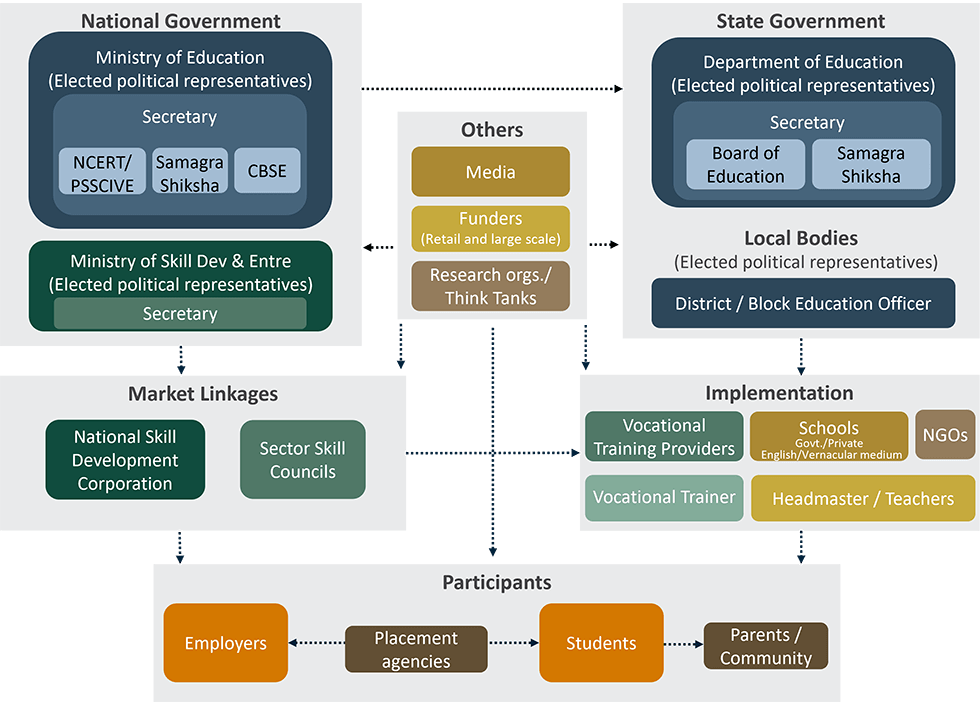

In parallel, the organization also seeks to change systems on a much larger scale. It is partnering with states to formulate and implement effective policies for vocational education. Here, the “systems” comprise both the government educational system and private sector employers. In other kinds of systems change work, the mix of public and private actors might be very different. The centerpiece is an initiative in four states to ensure that within six years they are on an irreversible and sustainable path to universalize quality skills education—potentially impacting one million students.

Achieving this sustainable, systemic approach to vocational education is the organization’s guiding star—the big goal it is always focused on. The root causes standing between Lend A Hand India and its guiding star include social norms on vocational education and careers and on girls pursuing an education and careers (particularly in rural contexts), the capacity to deliver high-quality vocational learning and internships, and connections between curricula and the skills required in life.

Like many organizations with deep direct-service experience, Lend A Hand India is not starting from scratch. It has spent years learning how the education and employment systems for young people, both public and private, work. Its guiding star and strategy are built on this understanding. “We’ve been doing this kind of partnership work in states for a long time,” explains Akash Patki, the organization’s senior manager for monitoring, evaluation, and learning. “But this is the first time we are trying to measure the progress or change we are able to bring in the larger ecosystem.”

Adds Raj Gilda, the organization’s co-founder, “First you need to develop a very nuanced understanding of how these systems work. Then you need to visualize what the change will look like.” The organization’s systems change strategy flows from its understanding of the education system at the state level and how this interacts with the needs of employers. And it’s deeply informed by Lend A Hand India’s close engagement with youth and their families, who experience the system and can share critical insights on how it works in real life.

A systems map is a “representation of the key elements in a system and how these elements interrelate,” according to ReImagined Futures, with the purpose of helping create a clear understanding of the elements and connections within the system and identifying the leverage points to create the desired shift. It can be simple and conceptual, or it can be detailed and specific, like Lend A Hand India’s. (See a schematic of Lend A Hand India’s systems map below.) One of the big assets that such direct-service organizations can bring to systems change work is this extensive experience working within a system. Often, they have learned a lot about the formal and informal barriers to progress and the ways around them. Indeed, they may already be working with others toward systems change goals, even if these goals are not yet fully integrated into their theory of change or their measurement and evaluation plan.

Identify measurable milestones and progress indicators

Lend A Hand India’s guiding star—setting India on an “irreversible and sustainable path to universalize quality skills education” beginning in four states—is an ambitious goal. So, the organization has set more measurable intermediate milestones for what it hopes to achieve over the next six years in each state. This includes the adoption of skills education components in the state’s education policy, skills education programming in at least 10 percent of schools, an earmarked budget, and a less tangible but just as critical (and measurable!) milestone, a shift in culture and norms, including the increased prevalence of girls making nontraditional course selection or career choices. Together, these milestones can help show the traction vocational education is getting and the ongoing resources needed to sustain it over the long term. And, based on its understanding of the education and employment system for young people, the organization has identified measurable progress indicators for each system change component at the state or local level, which can provide snapshots of what’s working, what isn’t, and for whom (e.g., progress in which geographies, demographics, and populations). A key goal is to ensure that internships are an integral part of vocational education. To this end, the organization has defined 18 different progress indicators related to this goal including dedicated budget and expense guidelines for internships, district engagement and monitoring for internships, and adoption of technology to monitor internships.

Girls taking a woodworking class at a school in India. (Photo: Lend A Hand India)

Girls taking a woodworking class at a school in India. (Photo: Lend A Hand India)

But, explains Patki, Lend A Hand India has staggered the 18 indicators over time. “Depending on how far along a state is, our government partners might say these three indicators are achievable for us this year. So, this is our dashboard for progress during the year. And we develop common definitions with them for each of those indicators and make sure there is a shared understanding of these definitions among our program partners at the state and national level.”

Lend A Hand India aims to be rigorous about measuring progress. “When we say a policy is adopted or something is achieved, we look for tangible evidence. Sometimes this will be in documents, but sometimes we get this from evaluation studies,” says Gilda. “We need government to see the real picture of what actually is or isn’t being achieved.”

Progress indicators in systems change work are needed if an organization and its partners are to have any insight about how the work is going—even if the indicators are only provisional and approximate. And seeing progress—even if only in smaller interim measures—can help sustain organizations and their supporters on the long difficult road toward change.

Tracking progress on systems change is hard, and Lend A Hand India is not doctrinaire about whether the progress indicator it is tracking is an output or an outcome. “When you are doing systems change, outputs are vital part of it,” says Gilda. “You need to know whether trainers are showing up in schools every day before you can measure whether a student is learning.”

Monitor the ecosystem

Milestones and indicators of progress—and even the overall measurement approach—will often need to change as an ecosystem evolves and as the organization and others in the field learn more about what it takes to succeed. Therefore, monitoring that ecosystem is critical to understanding changes in the key forces, stakeholders, barriers, and opportunities that are at the heart of systems change efforts.

And while an organization like Lend A Hand India, and its funders, may seek to identify and understand its own impact on a system, often the most it will be able to do is to describe its work alongside that of others and the progress of the field or system overall. This is the reality of working with others on systems change. “It’s not always about our own contribution,” says Patki. “It’s about whether the system will improve and sustain its progress, with or without us.”

Remember, too, that systems change inevitably means changing the status quo. And in many fields, there are powerful actors—people, organizations, institutions, communities—who are vested in the status quo and may push back at changes to systems from which they have benefited. Monitoring the ecosystem also means watching how these actors organize, shift resources to fight fires when they pop up, and learn from any losses to the opposition.

Adapt your strategy and methods along the way

It’s important to set down specific interim methods and measures—but in systems change work, it may be good to write them in pencil. Things change, the path will rarely be straight, and a good eraser may come in handy. “So much of this work we’re doing is driven by state officials,” says Gilda. “You can agree with somebody in the government on the criteria we’ll be tracking, but if the person in that position changes, then you may need to start over.”

If anything, this uncertainty makes measurement and learning more essential, not less.

* * * * *

Lend A Hand India is just one example of an organization with roots in direct service that is learning how to measure progress toward systems change. It has built a detailed map of the system, developed its strategy based on that knowledge, set both longer-term milestones for the work as a whole and intermediate ones that can be tracked over a much shorter period, and engaged partners in measurement and learning. Its guiding star remains unchanged. But it is adjusting to the fact that key elements of the work are outside its control, is thoughtful about monitoring changes in the ecosystem, and is willing to change its progress indicators or elements of its strategy as new challenges and opportunities arise.

Note: NCERT is the National Council of Educational Research and Training, an autonomous government organization that designs and supports a common system of education; PSSCIVE is the Pandit Sunderlal Sharma Central Institute of Vocational Education, an R&D unit of NCERT focusing on vocational education and training; Samagra Shiksha is a program that oversees a national initiative to improve school effectiveness; CBSE is the Central Board of Secondary Education.

Source: Lend A Hand India.