(updated February 2025)

How do you know if your organization or programs are achieving the impact you seek? How do you figure out how to get better at what you do? Performance measurement isn’t solely a yardstick for success—it’s also a tool for learning and decision making that helps you improve.

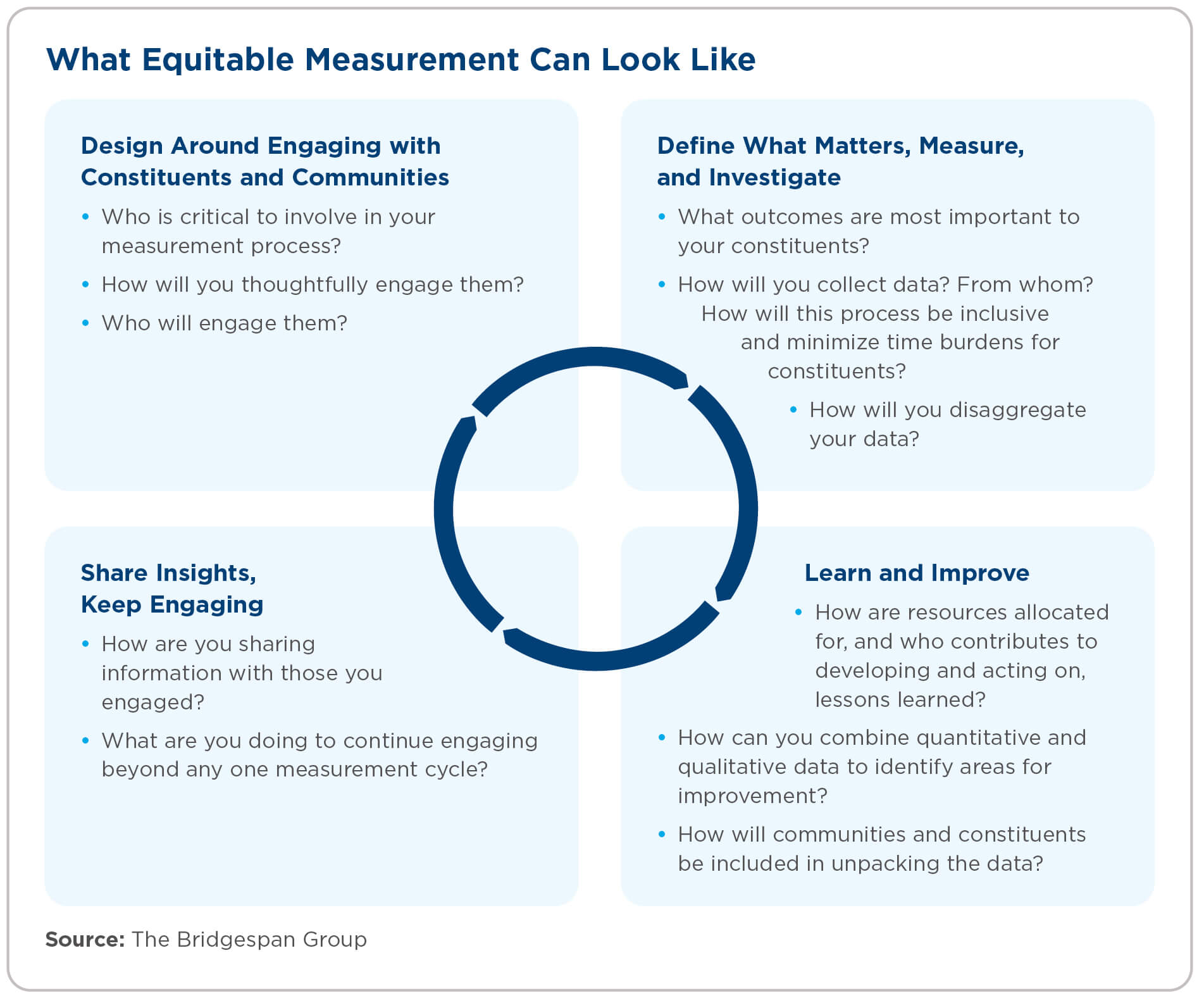

Indeed, the greatest value of performance measurement is in its power to help leaders figure out how their organizations can do better. And equitable measurement is vital to getting the full value out of an evaluation. Measuring with equity means incorporating a range of voices and viewpoints, including those with the least traditional power, and putting the challenges and solutions from your community and constituents at the core of how you think about impact. Communities and constituents know what they need better than anyone. As a result, they should be engaged as partners in the measurement process rather than as “beneficiaries.”

That was the crux of a 2020 letter to the Chronicle of Philanthropy written by staff from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the James Irvine Foundation, the Oregon Community Foundation, and other funders. They argued: “When evaluation is equitable, we begin with questions about who gets to assign meaning or value, what needs to be evaluated, and why a particular evaluation is selected. The understanding of impact will be incomplete, if not outright wrong, if the process is driven only by the interests and values of the most powerful stakeholders.”

Download Our Conversation Starter

Our step-by-step guide can help your team embed practices that promote equitable forms of measurement, evaluation, and learning into your improvement efforts.Download Now

Funders, of course, are powerful stakeholders, and they continue to exert a strong influence over how the social sector conducts performance measurement. Sometimes that can cause harm. But there is an ongoing shift in the field to provide nonprofits and NGOs with more space to tailor their measurement approaches less to the needs of funders and more to the needs and ambitions of the constituents and communities an organization serves. For example, organizations including the Equitable Evaluation Initiative and Fund for Shared Insight are catalyzing the field for equitable measurement and offer tools and resources from which nonprofits and funders can learn.

We at The Bridgespan Group are learning, too. Bridgespan itself, in the advice it has given philanthropy and nonprofits in years past, has contributed to bias and inequity. We have focused on quantitative metrics, which often do not tell the whole story and may lead funders to overlook organizations that don’t fit the narrow definition of “good” such measures create. We have at times equated “rigor” with randomized controlled trials, which can be prohibitively expensive for historically underfunded organizations, often led by people of color, and which are ethically questionable when they deny potentially valuable services and benefits to a control group.

As we ourselves have worked to incorporate equity in our measurement approach, we’ve seen more and more nonprofits and NGOs likewise seeking to measure with equity. This article shares some of these examples and offers practical advice for leaders on how to improve their evaluation and learning—by embedding practices that promote equitable forms of measurement, evaluation, and learning. Though the examples used in this article are from NGOs or nonprofits that provide direct services or advocacy (rather than intermediaries, field builders, or collaboratives), we believe the methods discussed here can be used by a wide range of social sector leaders who want to get better at weaving equity considerations into their day-to-day, year-on-year improvement efforts.

Design Around Engaging with Constituents and Communities

- Which constituents and communities are critical to involve in your measurement process?

- How will you thoughtfully engage them?

- Who inside or outside your organization will lead in these conversations and measurement activities?

"When a voice is missing from the table, the answers we get are insufficient. We may perpetuate bias, and fail to find out."

Ensure the constituents or communities with whom you work play a key role in the performance-measurement process from start to finish.

Nonprofits routinely work to put their clients or constituents at the center of their organization’s work. That level of authentic engagement should also extend to performance measurement. It is important to engage key stakeholders throughout the process, and particularly during initial design. It is also critical to close the loop with those same stakeholders, and to stay engaged with them beyond a single measurement cycle.

As the authors of the report “Why Am I Always Being Researched?” suggest: “The creation of research should begin from a place of mutual understanding between community organizations, researchers, and funders … to arrive at an authentic truth that does the most good for those” it is intended to benefit. To be sure, the discussion of whom to engage and how is infused throughout all practices that promote equitable forms of measurement, evaluation, and learning, as we explore in the following sections.

Consider how two organizations, Compass Working Capital and the Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED), are engaging communities in their performance measurement. “When we explain all the things we do to engage our clients in measuring performance, some people hear that and say, ‘Wow, that is so much work,’” says George Reuter, director of impact and innovation at Compass. “But it’s vital because our clients are our engine for how we can deliver better results.”

Compass is a nonprofit, based in Boston and Philadelphia, that supports families living in federally subsidized housing to build assets and financial capabilities as a pathway to greater economic opportunity, with a priority on serving Black and Latinx women.

The organization puts significant emphasis on engaging and collaborating with its clients. It surveys them after key program interactions with a Compass financial coach, then identifies respondents who express lower-than-average satisfaction in surveys and calls them—asking about their experiences with the program and any factors in their lives that may make it harder for the program to deliver results.

"We can just pick up the phone and call five clients and learn something right now."

“These conversations helped us identify the things that are blocks, where they are finding benefit from their interaction with their financial coach, and where they are frustrated,” explains Reuter. “[We can] just pick up the phone and call five clients and learn something right now.”

For example, in their interviews, some clients mentioned they wanted direct access to the resources and referrals coaches had, rather than always having to obtain them through their coach. “These interviews, and input from our Client Advisory Board, helped us think through how we could make some of the resources directly available through an app,” Reuter says. Compass’s Client Advisory Board, which comprises a cross section of the organization’s active clients, meets regularly not only to provide feedback but also to help Compass make sense of what it’s hearing from clients.

CAMFED, an NGO that supports girls in sub-Saharan Africa to go to school, learn, thrive, and lead change for their families and communities, puts engagement at the core of its service-delivery model—a model that requires a lot of data. A “detailed understanding of girls’ lives and educational experiences is vital to ensuring we can respond, and help schools respond, to the specific barriers girls face,” explains Katie Smith, chief strategy officer of CAMFED. “We need good school- and community-level data to do this. So, at every level, we are hearing from the constituencies we serve, and our clients are at the forefront of our planning and outcome setting and the monitoring and analysis of data.”

To collect data, CAMFED trains teachers as well as members of its 200,000-strong alumnae network of young women who have completed secondary school. “These women have a close understanding of the challenges girls are facing,” says Smith, “so there’s a lot of social capital in putting technology and data into the hands of those who understand and can use it. It turns what could be an extractive and unbalanced process into shared learning, which is helpful for people and the system they’re working in.”

Define What Outcomes Matter Most, Measure by Collecting Quantitative and Qualitative Data

- What outcomes are most important to your communities and constituents, and how do you know?

- How will you collect data, and from whom? In what specific ways will this process be inclusive? What is the time burden of this data-collection process for your constituents?

- What are the dimensions along which you will disaggregate your data?

Ask and investigate questions about inequities.

Noble Schools, a public charter school organization that serves approximately 12,000 high school students across 18 Chicago campuses, took important steps to define and investigate an issue of concern with strong equity implications: school safety.

“Noble Schools has been good at measuring student learning. We’ve done that well for a long time. But there’s more to the story than that,” says Matt Niksch, Noble’s former president. All of Noble’s schools are in urban Chicago neighborhoods, where they serve a predominantly Black and Latinx student population. But Niksch and his team knew that students in some Noble schools were dropping out at higher rates and facing greater challenges to success than those in other schools.

Neighborhood conditions were very likely playing a role in these inequitable outcomes. But the team needed more evidence. So Niksch analyzed publicly available data for a number of neighborhood indicators. While some didn’t seem to have much bearing on differences among schools, the analysis showed that the neighborhoods around two of the schools with some of the most significant concerns had substantially more crime than the others. Niksch and his team also knew that crime data was often a proxy for longstanding disinvestment in neighborhoods.

Jennifer Reid Davis, now Noble’s head of strategy and equity, but at the time a principal, had just taken charge of one of those two schools. “At my previous campus, I didn’t have to do much work about ensuring that the campus was physically safe,” Davis says. “But at this school, I was dealing with physical safety from the moment I got there.” While the school was safe inside, outside was another matter. Not only were there concerns about violence and gangs, but the public infrastructure around the school—streetlights, crosswalks—was in poor shape, and services were lacking. Recalls Davis, “My first day at the school, a kid at the stop sign got hit by a car—and I couldn’t get the police to come. That would never have happened at the previous Noble school where I was principal.”

The Noble team used several methods that are important for measuring with equity:

- They defined an important learning question (how might neighborhood factors be playing a role in student outcomes?)—one that didn’t automatically assume that it was students, parents, or teachers who were to blame for differential outcomes across schools.

- They considered root causes—or at least data that might be a proxy for a root cause like neighborhood disinvestment. This doesn’t mean a charter school can easily solve 6 root causes. But it does allow for a broader understanding of the problem that can lead to practical solutions.

- They looked at data that was both quantitative and qualitative. An analysis of neighborhood indicators was supplemented by hearing the direct experience of Davis and others about what was happening at the schools.

- They disaggregated the data on a number of dimensions, including student race and ethnicity and neighborhood characteristics.

Based on what it learned, Noble quickly allocated more funds to Davis’s school to address safety issues around the campus. “Within the first 30 days, we updated the entire camera system and began making other changes as well,” says Davis. “My staff felt the difference immediately, and it showed up in our survey results. In the area of school safety and perception of safety, we went from red to green in one year.” And it also used what it calls an “Equity Index” to spur broader organization-wide change—resulting in allocating funding based on need rather than equally to each school (see below).

While in this case, Noble needed to collect more (and different) data to better understand what was influencing school outcomes, more data isn’t always better. Data collection can place a real burden on both organizations and their constituents, so it’s valuable to consider whether there are certain kinds of data being collected that are less important, could be collected less often or from fewer people, or could involve fewer questions.

Measure what matters to clients and constituents.

Compass surveys the participants in its financial coaching program to learn how to make it better. It also seeks feedback about the questions it uses in the survey—and in doing so, it has learned a lot. For example, it has received important feedback from members of its Client Advisory Board. Because what mattered a lot to Compass was how its staff was doing and how it could improve, the survey questions focused on the coaches. “But the Client Advisory Board told us that our survey is too coach-driven, that it didn’t have anything to do with their own progress,” says Reuter. “So we revised the survey to allow clients to reflect on their own process instead of just how the coach was meeting their needs.”

Be inclusive about how you collect data in different communities.

Inclusion means knowing how and when to get to the key voices for understanding your impact. It’s important to understand cultural context. In some cases, it may be more appropriate to speak with some people outside of their homes, for example, rather than ask to enter. In other cases, a female head of household may not wish to speak in the presence, or in the absence, of a male relation.

Habitat for Humanity of Greater San Francisco, which builds and sustains home-ownership opportunities for families in three counties in the Bay Area, serves a substantial number of people from the Chinese diaspora, specifically the Cantonese-speaking community. To improve its ability to serve its Cantonese-speaking constituents, it sought quantitative and qualitative information from community members.

“At first, we just got a literal translation of the survey instrument,” says Angelica Resendez, Habitat’s vice president of home ownership services. “But when the results were not what we expected, we then had native speakers reread the survey to make sure the meaning wouldn’t get lost.” The practice of “back translation” helps to ensure that multi-language surveys are both accurate and relevant across cultures.

Habitat also hosted focus groups. “We wanted to go beyond the survey and hear from our newest homeowners, who were largely Chinese,” Resendez says. The organization works with numerous volunteers, so it was able to recruit people who were native Cantonese speakers to run the group. Another benefit of using volunteers rather than staff: it helped address some of the power dynamics that can exist between an organization and its constituents—opening the door to more authentic feedback.

Explains Resendez: “We shouldn’t be the ones asking these questions. ‘How is your first year of home ownership? What could Habitat have done better?’ If we ask, they might feel bad giving constructive feedback. With volunteers running the group, it would be neutral. And we didn’t host at our office. We hosted at a community space.”

Disaggregate data to identify trends, challenges, and opportunities.

Most organizations collect data that can be sorted by gender, race, ethnicity, geography, age, or other demographic categories. This is a good start. But these broad categories may obscure important inequities within other groups or communities that, without further disaggregation, will remain anecdotal or invisible. Effective data disaggregation can go a step further to truly understand how individual factors can influence a person’s experience with a program.

It can also be valuable in wider efforts to change systems. “Disaggregating data can help show government and other actors how a system needs to change,” explains CAMFED’s Smith. CAMFED ultimately relies on governments to sustain the changes in practices and outcomes that her organization is working toward.

“It can also model ways to improve the government’s own data collection,” Smith adds. For example, national education data might show that children have dropped out of school, but not why. CAMFED collects and disaggregates drop-out data to consider such factors as gender and disability. Its goal is to help governments tailor the way they allocate resources to achieve more equitable results.

Consider another example. The Boston Public Health Commission, seeing anecdotal evidence of health inequities between public housing and other city residents, added a single question to its biannual resident health survey asking whether people live in public housing, rent-assisted housing, or neither. Now, all the data in the health survey can be disaggregated by what type of housing a resident lives in, revealing glaring inequities in asthma, diabetes, and other conditions for public housing residents. This newly available data helped city and community-based agencies come together to address the inequitable asthma burden and other conditions and track progress in addressing them over time.

What these examples have in common is they are not just about fishing for more data. They are seeking to disaggregate data in order to shed more light on specific questions or hypotheses (such as whether public housing residents are affected by health inequities compared to residents of other types of housing) and to surface solutions that focus more on systems than on individual program participants.

Learn and Improve Based on the Data You Collect

- How are resources allocated based on what has been learned, and who contributes to developing and acting on lessons learned?

- How can you combine quantitative and qualitative data to understand areas for improvement?

- How will communities and constituents be included in understanding and unpacking the data?

Use what you learn to drive equitable decision making.

Let’s look at Noble Schools again. In some of its schools, student achievement was lower and dropout rates higher. What do you do with this information—how do you use it to improve rather than to blame or stigmatize? Noble collected data on factors like crime, homelessness, and the quality of feeder elementary schools for each school to create an Equity Index. A higher score (high Equity Index, or HEI) means the school faces more equity barriers, while a lower score (low Equity Index, or LEI) means it faces fewer of these barriers. “We publish this information internally,” says Niksch. “But it’s not about your day-to-day performance as a teacher or school leader. The Equity Index helps drive the allocation of funding, staff, and services.”

Noble is explicitly using its resources to fight some of the systemic inequities in the communities it serves—a significant change from treating every school the same, which left some schools without the additional resources needed to address the inequities in their communities. “When we first launched and published the index, I was the principal of what was going to be named the number-one equity campus,” says Davis. “So ours received more per pupil than anyone else. It also made a significant difference in how we could operate.”

The Equity Index also informs who’s at the table in decision making, she explains. Noble created several staff committees to revise policies on issues like hiring. “We made sure there was diversity in which campuses were represented—not just from LEI campuses but also representation from HEI campuses. Using our index helps us to do things in a way that represents the full scope of Noble. I can remember a time when I was the only teacher of color in some of those spaces. Our Equity Index holds us accountable in that way, too.”

"Using our [Equity] Index helps us to do things in a way that represents the full scope of Noble. I can remember a time when I was the only teacher of color in some of those spaces. Our Equity Index holds us accountable in that way, too."

Davis says that thinking in terms of HEI and LEI campuses also helps in analyzing data like its student experience survey. “It helped us see the vast difference in experience between students in some of the HEI schools versus some of the LEI schools— and think differently about where we spend our time and money. My hope is to use the index around the talent pool for hiring. We want to make sure our HEI schools have access to the broadest possible range of talent.”

Look at qualitative information alongside quantitative metrics.

“The goal of qualitative research is to understand a phenomenon from the perspective of the study participants, not from your perspective as a researcher,” Rachael Pierotti, who leads the qualitative work at the World Bank’s Africa Gender Innovation Lab, has said in an interview. Pierotti notes that qualitative research methods are important to “examine how a particular behavior or action is understood, or how people make sense of their circumstances.”

In Noble’s case, it combined quantitative data on neighborhood conditions with qualitative feedback from the school community to both quickly implement improvements in a specific school and develop an Equity Index that could guide the distribution of resources across the whole organization.

Then there’s CAMFED and its alumnae association. CAMFED provides alumnae with training and support to volunteer as “learner guides” in their local schools, where they identify girls who have dropped out of school or are at risk of doing so. It’s something they are well placed to do since, given their shared background, girls not used to being “seen” or consulted by authority trust them. Learner guides then mentor these girls, while also using what they have learned to ensure that the concerns of the most marginalized students are seen by school and community authorities and that those students get the support they need to stay in school.

Use client engagement to drive changes.

CAMFED uses data to deliver effective programs, and Noble Schools uses it to improve school conditions and more equitably allocate resources across their schools. Compass likewise uses its multiple ways of gathering client input—surveys, phone interviews, the Client Advisory Board—to identify how to change its financial coaching program to better reflect what clients say they want. For example, when Compass heard that clients wanted more direct access to its coaches, and more access themselves to the resources and referrals that coaches could provide, it brought this information to the Client Advisory Board, as well as some proposed solutions. Feedback from the board helped the staff change and refine some of those ideas, and helped Compass learn from clients about what the data meant and how it might respond.

Share Insights, Keep Engaging

- How are you sharing information with those you engaged?

- What are you doing to continue engaging on measurement and learning beyond any one measurement cycle?

Follow-up with your community and constituents to share insights.

A critical element in the measurement process is sharing what you’ve learned with constituents and community members who have helped in some aspect of the measurement process and, where possible, engaging them in discussions about potential solutions. Listen4Good, an excellent resource for nonprofits on the engagement process, calls this “closing the loop.”

Compass Working Capital uses a section of its website to report back on what it has heard from clients. “You said you wanted more opportunities to connect with other participants,” the website notes, and describes an effort it has made to respond to that feedback: a new peer-to-peer network that allows participants to talk with one another about their goals and plans.

CAMFED regularly shares the data it collects in schools with parents, school staff, and the wider community, and works with these stakeholders to draw up a list of specific improvement projects—like improving sanitation or school meals—based on what they learned together. Smith also underlines the importance of closing the feedback loop with bigger evaluation projects. “Big evaluations involve a lot of commitment,” she says. “They can be very extractive. Children are taken out of class to be tested; teachers are interviewed at length. It is important that they hear back and know what is being done with their data. And because schools and districts often don’t routinely have access to the kind of data we’re collecting in this kind of evaluation, sharing back the school- or districtwide data helps them come up with their own solutions to problems that an evaluation has spotlighted.”

Organizations, like people, should be lifelong learners. They should use what they’ve learned in one performance-measurement cycle, both about their programs and the measurement process itself, to develop new ways to think about equity, improve how they engage communities, and try out new approaches to achieving more equitable results— which ultimately lead to more impact.

Additional Insights on Equitable Evaluation

Here are a few articles and reports that have influenced our thinking on equitable evaluation. They may be of value to you as you seek to incorporate equity into your measurement, learning, and evaluation.

- Chera Reid and Shaady Salehi, “Toward a Trust-Based Framework for Learning and Evaluation,” Center for Evaluation Innovation, 2022.

- Why Am I Always Being Researched? Chicago Beyond Equity Series, vol. 1, Center for Evaluation Innovation (2018).

- Shifting the Evaluation Paradigm: The Equitable Evaluation Framework™, Equitable Evaluation Initiative and Grantmakers for Effective Organizations (2021).

- Valerie Threlfall, “Feedback’s Role in Shifting Power to Those Least Heard,” Listen4Good, February 22, 2022.

- Lymari Benitez, Yessica Cancel, Mary Marx, and Katie Smith Milway, Building Equitable Evidence of Social Impact, Pace Center for Girls and MilwayPLUS (2021).

- Leiha Edmonds, Clair Minson, and Ananya Hariharan, Centering Racial Equity in Measurement and Evaluation (Urban Institute, 2021).