Strategy is all about getting critical resource decisions right. The strategic planning process is a rare chance for a nonprofit’s leaders to step back and look at their organization and its activities as a whole—to understand what success looks like and to allocate time, talent, and dollars to the activities that can help achieve it.

When strategic planning is done well, it not only clarifies the path forward for teams and stakeholders, but also informs resourcing decisions and sets in motion key organizational changes. To be sure, it doesn’t always go well; we expect some readers may have had negative experiences with strategic planning. The practical advice we offer in this article will help leaders avoid the pitfalls and get real value from the process.

The best way to start strategic planning is by asking why you are doing it and what you want to get out of it.

When Strategic Planning Goes Wrong

Just as there are patterns to successful planning, there are several common ways strategic planning processes can go wrong:

- Everything but the kitchen sink. A logical list of things that would help the organization, but...it lacks overarching impact goals, choices, and prioritization on activities.

- The impossible dream. An inspirational plan, but...it does not account for the time, money, and skills required to get action items accomplished.

- The work plan. Clear activities and milestones, but...they do not consider risk or build in the flexibility to adapt to a changing environment.

- The manifesto. A bold plan, but...few support it other than the creator of the plan, and there is little connection to implementation.

- The spinning yarn. Tells a compelling story, but...there is little data supporting the new direction.

Consider Generation Hope. Founded in 2010, the nonprofit, headquartered in Washington, DC, helps teen parents succeed in college and experience economic mobility while driving systemic change for student parents nationwide. One in five undergraduates today is a parent, and yet they are much less likely to graduate than students without children. Through its direct-service work, Generation Hope supports teen student parents—primarily women of color—with services like mentoring, tuition assistance, and a peer community; provides early childhood programming to their children; and focuses on eliminating racial disparities for the students and families it works with.

After a decade of this direct-service work in the DC area, Generation Hope knew it was making a real difference. Now it was asking some big questions about its future. “Our work in DC was a proof point for what this could look like across the country,” says Nicole Lynn Lewis, founder and CEO of the organization and a former teen mother who put herself through the College of William & Mary with her infant daughter in tow. “We couldn’t serve every teen student parent in the US—but we knew we could help drive larger changes to benefit them.”

As Generation Hope began its strategic planning process, one thought-provoking question reverberated through the leadership team: given that we’ve demonstrated success locally, how might we improve the lives of more teen parents—and parents of any age—entering college? Motivated by this animating question to think bigger about its potential, Generation Hope began to develop a new strategic plan. (You can download a copy of their plan here.)

The Bridgespan Group worked with Generation Hope as well as with Living Goods, another organization described in this article, to support elements of their strategic planning process. Indeed, Bridgespan has had the opportunity to work with many hundreds of nonprofits and NGOs, large and small, as they developed strategic plans. In this article and our accompanying conversation starter, “Practical Questions Your Board and Team Might Ask About Strategic Planning,” we explore what we’ve learned through those experiences over the years.

Download our strategic planning resources

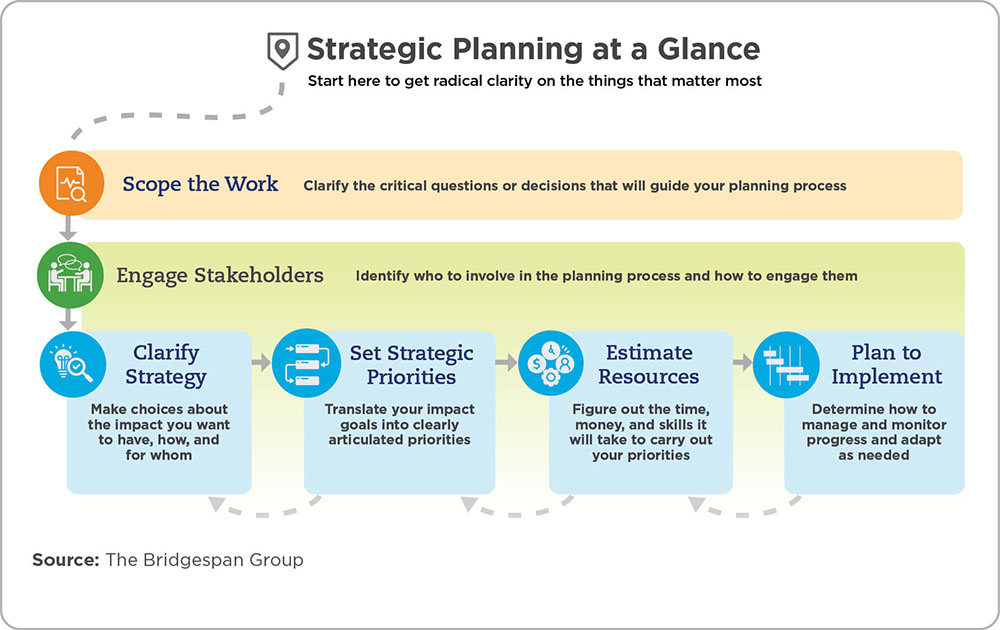

There are many approaches to strategic planning—and no one-size-fits-all template for the process. There are also many tools and techniques, which we provide throughout this article, that can be helpful along the way. (See "Useful Tools for Nonprofit Strategic Planning" for the full list.) But making key decisions and getting real value out of the process comes down to just four vital elements:

- Clarify strategy. Make choices about the impact you want to have, how, and for whom.

- Set strategic priorities. Translate your impact goals into several clearly articulated actions and activities.

- Estimate resources. Figure out the time, money, and skills it will take to carry out your strategic priorities successfully.

- Plan to implement. Determine how to manage and monitor the organizational changes required to execute your strategy.

Let’s look at each in turn—recognizing that these elements are as much iterative as they are sequential.

Click the image to see a detailed overview of the strategic planning process.

Click the image to see a detailed overview of the strategic planning process.

Clarify Strategy

Make choices about the impact you want to have, how, and for whom

Developing a clear, effective strategic plan often takes at least several months and may require difficult tradeoffs. To answer the key questions that typically drive the planning process will require revisiting your organization’s most important goals—your intended impact—and thinking about how you will achieve that impact, known as your theory of change.

Impact goals are more tangible and measurable than an organization’s longer-term mission and vision. Ideally, they focus on the next three to five years—long enough to allow for meaningful change, but not so long that the path to achieving that change is vague and undefined. Getting clearer as an organization on your three- to five-year impact goals and a plausible path to achieving those goals can help answer a broader set of questions critical to developing a sound strategy.

Click below to read the strategic plans from the organizations featured in this article:

Generation Hope >>

Living Goods >>

As Generation Hope began to develop its three-year strategic plan, it gathered information on its strengths and weaknesses and on how changes in the external environment might affect it. Based on what it learned, Generation Hope felt ready to go from primarily delivering direct services in the Washington, DC, area to combining direct service with technical assistance to higher-education institutions and advocacy for policy change nationwide—a new approach it articulated in its plan:

Generation Hope will drive systemic change to address historical racism and remove barriers for teen/student parents and their families by implementing a federal and local policy and advocacy agenda, transforming the higher-education landscape through … institutional capacity building … and providing resources and tools for the broader higher-education and workforce community.

Notice what this description of its approach does and doesn’t communicate. You couldn’t simply hand it to staff and say, “Go do this.” It doesn’t say how much, when, or with what resources. But you can’t get to those questions without making the kinds of decisions reflected in this approach. It sets out how they intend to achieve impact, with specifics still to be determined.

Indeed, Lewis explains that this description, in turn, raised big questions about what to do next. Her team asked, she says: “How were we going to put those different pieces together and ensure that our leadership team and board had a common vision of that strategy and [were] able to execute on it?” We look at how Generation Hope answered these questions in the following sections.

Another organization whose strategic planning process led to changes in how it achieves impact is Living Goods, an NGO headquartered in Kenya. Living Goods trains and supports community health workers to deliver quality health care to their neighbors’ doorsteps. Over a decade and a half, Living Goods has trained over 12,000 health workers who have reached over nine million people. And it has learned how to deliver community health care at an annual per capita cost of $3 to $4, ensuring a high return on investment for Living Goods, governments, and other partners.

Still, “we were grappling with a couple of big questions,” explains Emilie Chambert, the organization’s chief program officer. “For example, we increasingly understand that if government owns the community health worker model rather than us, it will make the work much more sustainable in a country. We’ll make the initial investment, but government funding will need to play a larger role—so that, in four or five years, the government will fully own and finance the community health worker program. We needed a plan to get to that kind of government ownership.”

In its most recent strategic plan, Living Goods explains that “this strategy represents a material evolution” of its work from providing health services itself to relying on governments to scale and sustain that work. The Living Goods strategic plan is a good example of being clear about what will change compared to the past—a useful signposting of “from–to” that helps communicate strategic changes to external stakeholders and an organization’s own staff.

A Generation Hope Scholar poses with her daughters and mentor at the 2022 Hope Conference. (Photo courtesy of Generation Hope)

Set Strategic Priorities

Translate your impact goals into clearly articulated priorities

Once an organization has set out what it wants to achieve, it must decide how to accomplish its goals. Typically, strategic priorities consist of several—typically, no more than five to seven—multiyear initiatives that will advance the overall goals of the plan and contain enough detail to create a good idea of how the work will unfold. Strategic priorities don’t need to cover all of an organization’s work; instead, they often focus more on high-stakes changes to how the organization will work than on business as usual. (Don’t get hung up on distinguishing between a strategic “priority” or “initiative,” or an “activity” or “objective.” If you look at the plans from Generation Hope and Living Goods, you will notice that they use different ways of organizing the material, but convey a similar level of detail and clarity regarding what they’re planning to do.)

Create a plan to integrate insights from your nonprofit's clients, staff, board members, funders, and community partners with this free toolkit.

Recall one of Generation Hope’s key strategic goals—driving systems change through technical assistance and advocacy. Like many of its most important decisions, this meant that things would not be business as usual. The organization, long focused almost entirely on direct service, would have to find new ways of working. As a result, the organization’s plan sets out several specific priorities under this goal—each just a sentence long. For example:

Join and support an ecosystem of higher-education and public and private partners centered on student parents’ experiences, resulting in 10 new collaborations by the end of FY24.

Another priority Generation Hope articulated:

Develop, test, and build upon a technical assistance program that partners with anti-racism experts to build capacity in student parent success and intersectional issues, resulting in at least 20,000 student parents impacted by 2024.

Both of those priorities, short as they are, represent important decisions about what Generation Hope will do, when it will do it, how much it will do, and how it will know if it’s successful. It is worth spending a good deal of time to arrive at these kinds of decisions and to pressure-test them with staff, board, partners, and other stakeholders.

The points also illustrate how strategic planning is an iterative process across its four key elements. Without some serious information gathering and conversations about needed resources and infrastructure, it would be impossible to know if “10 collaboratives” or “20,000 student parents” are conservative, ambitious, or unrealistic targets. “We proposed different scenarios for growth. We discussed things together,” explains Lewis. “We had task force members name things that didn’t feel tangible or felt too ambitious, and we made changes.”

Both priorities are in the form of “do more”—with the objective about collaboratives reflecting a significant expansion of Generation Hope’s previous partnership work and the technical assistance objective being essentially a whole new program. But equally important to an organization’s strategy can be decisions about doing less, or in some cases stopping something altogether. For organizations with multiple programs, mapping its programs to its goals can be powerful for visualizing and understanding the performance of its programs in the context of the strategy—and for making decisions about where to invest more resources and where to invest fewer.

The Living Goods plan has a section entitled “What We Will Not Do.” For example, underlining its commitment to scaling its community health worker model through government funding, the plan states that it

[will not] engage in scaling Living Goods-led community health delivery. Going forward, the only Living Goods-led delivery we will invest in will be those that operate as learning laboratories.

Decisions to stop doing something can be among the most difficult strategic decisions an organization can make—involving staff, funders, and other constituencies who are deeply involved in the activities that will be shrunk or ended. These decisions can also be critical in changing an organization’s path forward. In our strategic planning work with nonprofits and NGOs, we have seen organizations give up programs, withdraw from geographies, forgo once-significant funding sources, or curtail whole categories of work—not because they needed to retrench, but because they came to understand that achieving greater impact required a different focus.

The choice of priorities can also make big aspirations much more concrete and actionable. Living Goods, for example, wanted to sharpen its priorities around diversity and equity. Like many NGOs founded in the Global North but working in the Global South, it has been seeking to move its center of gravity to the places where it works. As a result, it recently appointed a Kenya-based CEO, and 95 percent of its staff is based in East Africa and native to the countries in which they work. But it has also committed to doing more, including the following priority:

Ensuring local teams are in place and in leadership roles across our countries, deepening engagement with our in-country advisory boards, and continuing to diversify our global board to ensure that at least 50 percent of members are of African descent.

Estimate Resources

Figure out the time, money, and skills it will take to carry out your priorities

Even the boldest and most ambitious strategic plan must also be feasible. You want to have a good sense of how much time and money it will take, who will put in that time, and where the money will come from.

To be sure, sometimes the resourcing needed for what is envisioned may end up being out of reach. This is a place where iteration in a planning process is crucial. It’s completely normal for teams to adjust their goals and the scope of their priorities as they estimate the time, money, and skills those goals require.

With a lot of “do more” in Generation Hope’s plan, the organization used its strategic planning process to think hard about the resources and infrastructure that would be required—and how to fund them. “This was an ambitious plan,” says Lewis, the CEO. “It called for growth across all departments, and we had to create two new departments to carry out parts of the plan.”

For example, seeing the board as critical to achieving its impact goals, Generation Hope sought to increase board capacity, including developing

training and accountability systems for committee chairs, resulting in 90 percent of board members feeling engaged in committee work by 2024.

It also resolved to recruit

board members with a national network to assist in scaling and fundraising efforts while maintaining our diversity goals, resulting in at least one new member with this background annually.

As you consider what additional capacity you will need to make your plan a possibility, you may also find that your organizational design is no longer a good fit with the new strategic priorities and that you need to redesign the reporting structure or make changes to how you deploy people and resources. These are all elements of your organization’s operating model. Strategic planning can be the right time to ensure your organization has the right systems and processes in place to achieve impact more effectively and sustainably.

Living Goods likewise used its planning process to understand the capabilities required to carry out its strategic priorities. The organization has long incorporated a focus on digital tools, data, and innovation as drivers of impact—for example, ensuring that community health workers can provide accurate care and prompt follow-ups with a smartphone app that details every patient contact, enables near-real-time performance management of health workers in outlying villages, and detects early disease outbreaks. In its plan, it makes concrete the activities and investment required:

We will introduce disruptive innovation, which may include incorporating existing approaches not widely used in community health today, and investing selectively in cutting-edge, new approaches where it will be important to partner with others … with an estimated spend of five to 10 percent of our organizational budget.

Note that the organization is proposing to strengthen its technology efforts in part by partnering with others, rather than building this capacity entirely on its own. For some organizations, partnerships can be a critical element of the strategic plan.

Organizations will likely also need to think about whether their current funding model is well suited to a new strategic direction. This may be particularly relevant if the organization is taking on new activities that are likely to attract a different type of funder or payer. During the planning process, Generation Hope worked to gauge interest among funders about the new systems-change work it was taking on.

For Living Goods, the biggest shift in its strategy was toward government co-financing for the work, the financial implications of which are spelled out in the plan:

Over the next five years, we will aim to unlock around $70 million in co‑financing across implementation support sites. … This will halve Living Goods’ costs per community health worker and reduce cost per capita from $4 to $2.

For organizations whose strategic plans envision significant growth, as with Generation Hope and Living Goods, there can be a lot of uncertainty about what level of growth it can afford and how much it can raise. “Our finance team developed a model that helped us build different scenarios—low, middle, and high,” says Living Goods’ Chambert. “We’re so glad we had these different scenarios, because the context has changed a lot since the plan was developed. When we started, there was no recession on the horizon, no war in Ukraine. Now we are using our middle scenario, and we’ve had to adjust the number of countries we’ll be working in.”

Plan to Implement

Determine how to manage and monitor progress and adapt as needed

Implementation mainly happens after an organization has finished its strategic plan. But the odds of successfully implementing the planned changes—shifting parts of the organization in a new direction, setting up new initiatives, curtailing old ones—can depend a lot on what you do during the planning process or shortly thereafter. As one leader we interviewed advises: “There’s a culture piece that needs to be considered at the same time as the rest of the plan. Change management needs to be built in from the beginning.”

Generation Hope, for example, had gained a lot of value from engaging staff and the board around strategy during the planning process, so it continued some of that engagement even after the plan was done. “Because we were launching an ambitious plan at the onset of a global pandemic, we knew we were navigating a lot of uncertainty,” explains Lewis. “So we baked in more check-ins with our board than we’d usually do. Here’s what we’ve accomplished, here’s what’s been hard, here’s what we want to do differently.”

The organization does the same with its staff. “I don’t think our staff has ever been more informed about the organization’s direction,” Lewis adds. “We just did a pulse check survey: Do you understand the goals of our strategic plan? About 95 percent said ‘Yes.’”

There are a range of tools organizations can use to help stay on track. For example, implementation plans lay out the steps, sequence, owner, and metrics for each key activity, while performance dashboards track and communicate progress using a few vital metrics that the leadership team and board need to monitor in order to understand and manage performance.

Remember, too, that every strategic plan and its strategic priorities have risks. The planning team can brainstorm key risks, considering questions such as:

- What could happen that would make the implementation of this plan difficult?

- Do you anticipate shifts in the external landscape due to funding, politics, or otherwise?

- Are there uncertainties with implementing a new program?

- Are there possibilities of internal capacity gaps?

A learning agenda can be important in helping to mitigate and manage some of these risks and uncertainties. For example, in thinking about its core model, the Living Goods plan notes that the organization wants to learn more about current inefficiencies in its model, service delivery, digital aspects, the use of supervisor time, and several other areas so that it can address the most significant inefficiencies and improve its results.

For some organizations, a learning agenda may include full-scale research. But there are also faster learning strategies. In her book Lean Impact: How to Innovate for Radically Greater Social Good, Ann Mei Chang, CEO of Candid and a former Bridgespan fellow, argues that organizations looking for answers to critical questions about how to deliver on their strategy can “run fast experiments to accelerate the pace of learning, save time and money, and minimize risk.”

Even the best strategic plan is unlikely to nail down all the answers or make all key decisions that will need to be made. For example, during its strategic planning process, Living Goods didn’t decide which new countries it would expand into in the future. But it did set up decision criteria for expansion—stating that it won’t enter a country if it knows from the start that the country is unlikely to become core to its work or has not indicated sufficient willingness to increase government ownership and investment in community health.

***

Strategic planning can help improve how an organization makes decisions. The questions posed during the planning process are not the sort you answer only once. Rather, leaders will likely find themselves applying the same approach to opportunities and questions down the road. That is one reason why many nonprofits and NGOs find strategic planning to be so transformational.

How To Conduct a Focused, Exploratory Strategic Planning Process

It’s valuable to define key strategic questions at the start of the process. But in a good strategic planning process, leaders also need to be willing to discover and act on information that goes against their initial assumptions.

By engaging those who know your organization best from different vantage points—staff, board, clients, funders, community members, partner organizations, and others—you can learn a lot at every stage of the planning process. Thoughtfully engaging with key stakeholders is also important from a change-management perspective, because decisions and actions that result from your strategic planning process will affect everyone connected to your organization as well as the broader community.

For example, Generation Hope understood how critical its board would be to developing and supporting its new strategic plan. It convened a planning task force of five board members and three of the organization’s top leaders, as well as coordinated a two-day retreat with the full board near the beginning of the process—and has continued to involve its board at every step.

It also engaged other vital stakeholders. “We talked to higher-education professionals, and we talked to student parents,” says Nicole Lynn Lewis, founder and CEO of Generation Hope. “We held four listening sessions with folks across the country. We did a lot of listening.” It also conducted stakeholder interviews, engaged program alums and current and potential funders, used an internal assessment tool, conducted a landscape analysis, and incorporated guidance from Equity in the Center to explore the levers that drive organizational change and transformation in the context of racial equity. “We wanted to ensure our racial equity work was resourced effectively and woven into our own racial equity blueprint,” says Lewis.

It can be worth using a variety of methods to gather ideas and input. “We were pretty clear on where we were as an organization and didn’t end up learning much from the internal assessment [we conducted],” recalls Emilie Chambert, Living Goods’ chief program officer. “But the external analysis and external stakeholder engagement were really helpful.” For example, a benchmarking analysis of peer organizations working in Africa (involving interviews with five organizations and desk research on two others) helped Living Goods better understand key elements in successfully partnering with government.

Engagement and information gathering can help ensure that your strategy is a good fit with your unique assets and relevant external trends, and that it considers feedback from board, staff, community members, and other constituents. All are key not only to the design of the plan but its later implementation.

Download Strategic Planning Resources for Nonprofits

Please fill out the form below to download the toolkit. We use the information we collect to help us improve our content and to inform our funders about the impact of our work. We will never share your personal information with any third party without your permission. This toolkit includes:

- How Nonprofits and NGOs Can Get Real Value from Strategic Planning. A PDF of this article and its resources share four vital elements common to most strategic planning approaches.

- Strategic Planning at a Glance. A one-page guide to the strategic planning process.

- Practical Questions Your Board and Team Might Ask About Strategic Planning. Frequently asked questions and answers to help you better explore your organization's readiness and preparedness to start a strategic planning process

- Useful Tools for Nonprofit Strategic Planning. Definitions for a number of useful tools common to the strategic planning process and describe how they are used.