Leadership transitions represent a pivotal moment to reflect on the changes required within an organization—and on how funders and board members can set these leaders up for success. Leaders like David Gaspar, CEO of The Bail Project, argue powerfully that the point of transition to a new leader is an important time for funders to lean in. “[This is the] most critical time for [funders] to lean forward,” he says. “I need people to support my leadership because the world is watching.”

A Transition Timetable

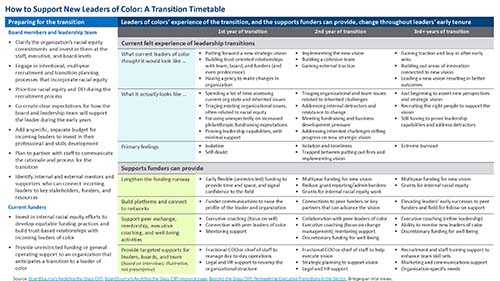

The experience of leaders of color while transitioning into leadership roles, and the supports funders can provide, change throughout leaders' early tenures. Our timetable shares how organizations can prepare for leadership transitions, how new leaders feel about their experiences, and what funders can do during the first few years to support new leaders of color.

The experience of leaders of color while transitioning into leadership roles, and the supports funders can provide, change throughout leaders' early tenures. Our timetable shares how organizations can prepare for leadership transitions, how new leaders feel about their experiences, and what funders can do during the first few years to support new leaders of color. Download the PDF or read the timetable online >>

Systems of supports are critical for all new leaders. Any nonprofit leader assuming the CEO or executive director role for the first time faces pressures: to meet fundraising goals, to build productive relationships quickly, or to resolve problems inherited from their predecessors. There are entrenched assumptions, norms, and practices—for leadership teams, boards, partners, and other stakeholders, notably funders—that have long been relied upon to support new leaders.

After years of underrepresentation, the social sector is finally seeing more leaders of color transitioning into executive leadership roles as nonprofit organizations and philanthropies seized on opportunities following the nationwide discussions about racial equity spurred by the murder of George Floyd. With these new leaders, we have indeed seen successes and gains attached to the promise of more equity and equitable impact.

Leaders of color bring fresh and nuanced perspectives to nonprofits. Their distinct leadership assets complement the skills and experiences that have positioned them for these executive roles. Informed by their own lived experiences, they often see the communities they serve as partners in solving the problems those communities face. As a result, these leaders are reimagining programs and practices and co-creating innovative solutions with the potential for greater impact. This puts leaders of color in a unique position to fundamentally transform their organizations. This is especially true within organizations that may not have previously oriented themselves through an equity or systems change lens. Indeed, this is the forward momentum that many in the social sector have been longing for.

Yet, unleashing the greatness these leaders bring is tightly connected to support from funders, board members, and others—who often have not fully aided these leaders in the transformative changes they seek to implement. This support is critical for leaders of color, who face unique challenges as a result of systemic racism and institutionalized forms of bias. These challenges are even more pronounced when following a white predecessor. Thus, leaders of color often enter new leadership roles without critical supports that would help them thrive and flourish.

As a result, many of these leaders are leaving. To their credit, some leave able to take a victory lap after heroically shepherding their organizations through a period of multiple reinforcing crises—a global pandemic, racial justice uprisings, and anti-DEI agitation—that created additional work and took an emotional toll. For most, though, the weight of their experiences has become too much.

The good news is that there are concrete ways to support these leaders and retain the progress that has been made. Funders play a catalytic role and have a critical opportunity to further equitable impact in the sector. Based on our research and interviews with more than 30 leaders of color—and years of engagements with nonprofit leaders—this article outlines four ways that funders can invest in leaders of color during times of transition.

What Underlies the Experiences of Leaders of Color?

Research from Building Movement Project, as well as from Bridgespan, reveals that leaders of color often face:

- Interpersonal bias and exclusionary behavior from funders and boards, inhibiting relationship-building

- Racial bias in philanthropy that emerges from issues such as inequitable access to the social networks that support fundraising

- Pressure to take on too much work themselves rather than relying on board members or asking for help

- Heightened scrutiny and expectations—particularly from staff of color—to quickly advance racial equity in their organizations

Further, many leaders of color are brought into organizations that are already in crisis to solve problems they didn’t create and are expected to implement change in short order—a phenomenon referred to as the “glass cliff.” Often, they also find themselves in a trap known as the “double bind” due to the limited range of behaviors deemed acceptable for them. As one executive of color we interviewed commented, “I’m either too direct or not assertive enough.” Avoiding such traps is exhausting and takes time and energy away from leaders’ efforts to be who they want to be in their roles.

Compounding matters, Black women comprise many of these new leaders of color. A study by the Washington Area Women’s Foundation of Black women and gender-expansive nonprofit leaders revealed a fundamental absence of trust, causing their leadership and decision making to be constantly questioned, challenged, and undermined. While this lack of trust showed up in specific areas such as fundraising, board engagement, staff management, and wellness policies, these leaders are plagued by a pervasive skepticism about their overall capabilities. The writer Shauna Knox, senior vice president of the National Black Child Development Institute, described the consequences as “the impossible dilemma of Black female leadership” in a Nonprofit Quarterly article—“a choice to drown or to disappear,” undermining the transformational potential of their leadership.

In the face of such challenges, many leaders of color are burning out and leaving their jobs. Building Movement Project’s report, The Push and Pull: Declining Interest in Nonprofit Leadership, revealed that 41 percent of nonprofit leaders of color who are thinking of exiting cite burnout as the primary factor. Nonprofit staff of color, meanwhile, express declining interest in even striving for these leadership roles.

As leaders of color ourselves, we also have felt this weight, either firsthand or in walking alongside our partners or clients.

Four Ways Funders Can Support Leaders of Color During Transitions

Leaders of color can thrive and flourish in new leadership roles with intentional support. Funders often hang back during a leadership change, waiting to see how a new leader is doing before committing their full support, says Bail Project’s Gaspar.

Our research suggests they should instead lean in to support leaders of color during this critical time. In our study of leadership transitions of leaders of color and our work with more than 350 leaders, as well as speaking with Bridgespan clients, we’ve identified four tactics funders can employ to support these leaders during this critical time. Each tactic provides practical benefits that would be useful for any new CEO while also helping new leaders of color deal with the systemic barriers they face. The objective is to create conditions for these leaders’ long-term success.

Lengthen the funding runway

Flexible, unrestricted grants are the holy grail for most nonprofit leaders. For new leaders of color, they can be especially valuable. Flexible grants can eliminate pressure to focus immediately on fundraising and provide leaders with the time and space needed to reimagine their organizations in accordance with their own visions, which may differ significantly from that of their white predecessors, as well as the means to fund a new program or strategic priority. Such grants give these leaders the ability to address immediate needs within their organizations without fear of going off a fiscal cliff later—a fear that may stifle risk-taking, innovation, and creativity.

Flexible grants can also knock down some of the systemic barriers leaders of color face because of racial bias in philanthropy. Given the trust gap that incoming leaders of color, particularly those without previous executive experience, typically encounter with white funders, flexible gifts can demonstrate the donor’s confidence in the new leader to other funders and the field. Working alongside a leader of color in transition, Kim Dempsey, former capital markets executive at Housing Partnership Network, saw the power of this approach firsthand when a funder gave flexible grants. Such grants signal to the world that “I'm going to invest in you because I believe you are the kind of leader that needs to take this organization to its next level of impact,” she says.

In the long term, unrestricted grants can create new conditions for success by reducing long-term pressures to focus on fundraising, giving leaders of color time to rethink their roles as fundraisers.

Build platforms and connect to networks

As we have noted, leaders of color often bring, or can build, deep connections to the communities their organizations serve. Yet, they also have been excluded from the key social networks that help a leader cultivate major donors or that open doors in policy spaces.

Gaspar of The Bail Project highlights how funders, with resources that include broad networks of power players, can have the most transformative impact when they go beyond simple introductions to people in their networks to truly facilitate relationships and give more than their money to the cause. It’s “not just enough [that they] lend some money to [the cause],” he says, “but to actually lend their credibility, lend their name, lend their support for ways that actually advance the work.”

Whether through a grantee spotlight in a key publication or a warm introduction to peers, funders can help raise the profile of a new leader of color and provide access to valuable networks. Moreover, like unrestricted grants, these forms of support can also serve as public votes of confidence, with the add-on benefits such endorsements bring.

High-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) can also play a particularly important part in providing support for new leaders of color during leadership transitions. Bridgespan’s research on founder transitions highlights the key role outgoing leaders can play in brokering relationships with their high-net-worth donors for incoming leaders. This is especially helpful for leaders of color, as it can help overcome the traditional barriers to philanthropic capital that make accessing HNWIs difficult and time consuming for them.

Support peer exchange, mentorship, executive coaching, and well-being activities

All new leaders can benefit from personal support systems—including connections to peers, mentors, and coaches—during transitions. Yet, research by Building Movement Project on building the capacity of community-based organizations, and Bridgespan’s client work, show that leaders of color face significant challenges in finding personal support systems that share their identities or have experiences addressing the subtle—or not so subtle—ways that systemic racism creates headwinds for leaders of color. Funders can underwrite such opportunities and well-being activities that center the identities, assets, and needs of new leaders of color.

These supports are critical to leaders’ resiliency. The Surge Institute (of which one of the authors, Carmita, is founder and CEO) demonstrates the transformative power of building and practicing executive and interpersonal skills in a true “container of care” with other leaders of color. Surge creates spaces grounded in a belief in the innate brilliance and strengths of these leaders—spaces where they can also address their pressing needs as senior executives. This combination of affirmation and attention to needs is essential for enabling leaders of color to experience vulnerability, healing, and restoration, and to develop rapidly as leaders. Other examples of such opportunities include The Highland Project, the Black Leadership Social Capital Initiative in North Carolina, and the Black Nonprofit Chief Executives of Philadelphia.

Provide targeted supports for leaders, boards, and teams

Nonprofit leaders can benefit from funders underwriting targeted supports during a leadership transition. For example, several leaders we spoke with highlighted the importance of fractional support from individuals in part-time and often project-based executive positions who provide strategic support and expertise to leaders early in their tenures. Fractional support can also take the form of legal or HR assistance to help a leader revamp organizational structure, a chief of staff to manage day-to-day operations, or marketing support for expanding outreach for fundraising.

As with unrestricted funding, it is critical—for this support to be as effective as possible—that leaders of color determine where such capacity-building assistance will have the most impact. That means funders trust leaders of color to identify the supports they need and collaborate with them to furnish these targeted supports.

Furthermore, targeted supports should not be reserved just for new leaders. Boards need them, too. Training for board members can be extremely valuable. For example, BoardSource and Building Movement Project developed a resource to help boards prepare for every stage of a leadership transition—before, during, and after—so they can “proactively navigate pitfalls and support the success of incoming leaders of color.”

Funding Transformational Change

When new leaders of color are not given the support they need, we collectively miss out on perhaps the most fundamental and far-reaching gift these leaders have to offer: the ability to re-envision organizations so they can more holistically serve their communities today and develop approaches to combat root causes of social injustice for a better tomorrow.

Nonprofit leaders of color and their funders share ambitious goals and seek transformational, population-level impact. This is especially true when their organizations serve BIPOC and low-income communities that bear the burden of inequities woven into the interconnected systems (e.g., education, public health, housing, employment) that have historically oppressed and devalued them.

These leaders’ goals are not just about individual program outcomes but also about building the collective power of communities to advocate for themselves and advance policy agendas that would change the conditions in which many communities are struggling. In keeping with these goals, many leaders of color desire a more expansive definition of success, one grounded in what community members have identified as what they need and desire to thrive over generations. And lest we overemphasize the serious work of social change, leaders of color also tend to lead with connection, meaning, and joy. Who doesn’t want that as part of their organization?

Each individual form of support a funder provides—whether flexible grants; platforms and networks; peer exchange, mentorship, coaching, and well-being activities; or targeted supports—is a step toward realizing this vision. As Aisha Benson, president and CEO of the Nonprofit Finance Fund, states, these kinds of supports not only enable leaders of color to “lean into their strengths” but also demonstrate funders' commitment to building trusting relationships with new leaders of color. “If funders really want to walk the talk around racial equity, there has to be… an even deeper level of trust in a leader of color coming in,” she says.

As funders and leaders continue to partner, this relationship should evolve year by year. Our conversations with leaders of color indicate that different supports are needed as a leader’s tenure progresses. (See “How to Support New Leaders of Color: A Transition Timetable,” which lays out what forms of support these leaders tell us are most helpful at which stages of their leadership transitions.)

We know that this is possible, and we have seen funders taking intentional steps in this direction. For example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is embracing this moment by supporting a cohort of community development organizations undergoing leadership transitions with general operating support. Impact Investment Lead Zoila Jennings believes these grants will contribute not only to innovations at organizations with new leaders of color but also to protecting organizations during sensitive periods of transition. “If they're not supported [at these times], it could really cause a lot of organizational, financial, and operational challenges,” she says. And, ultimately, “it’s about supporting the sustainability of an organization over the long term.”

* * *

Leaders of color are ready to translate their talents and gifts into meaningful change. Let’s imagine and realize a world where all leaders—whatever their identities—receive the support they need during the natural cyclical transitions of any thriving organization. Now is the time for funders to step up and support them with the time, space, and funding to catalyze equitable impact across the social sector.

Acknowledgments

This article was developed with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors thank Bridgespan colleagues Alison Kelley, Cora Daniels, Darren Isom, Meera Chary, and Preeta Nayak for their contributions to this work. We thank Dan Penrice and Larry Yu for their editorial support. And, for their expertise, guidance, and insights, we also thank everyone we interviewed or spoke with, and those who reviewed drafts.

Bridgespan recognizes we are echoing the messages of the many leaders of color who have championed representative leadership and fought to create the conditions for leaders of color to succeed.