Developing and retaining talent is a perennial issue for nonprofits and NGOs around the globe. It’s a source of worry, for some, as they carefully monitor employee turnover. The ability to develop leaders is inextricably linked to retaining them: over 40 percent of voluntary turnover among nonprofits is due to “lack of opportunity for upward mobility/career growth,” according to a Nonprofit HR survey.

Jump-start your own leadership development process with ready-to-use templates and resources.

Download

It’s a source of opportunity for others. Most organizations, even the ones firing on all cylinders today, know they still need to prepare for tomorrow. Indeed, nonprofits fill their top leadership positions through internal promotion only half as often as for-profit companies, pointing to the need for more nonprofits to focus on their next leaders. And most are as committed to advancing the lives and careers of their team members as they are to pursing their missions.

A more formal approach to leadership development is also an opportunity for nonprofits to advance goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The systems they use to assess and develop talent are what Race Forward terms “choice points” that either accelerate or block the path to a more inclusive and equitable workplace. The leaders who will take missions forward tomorrow can’t be a carbon copy of today, not if organizations hope to bring the best of their teams and communities to bear in the work. A leadership development system can drive professional growth for a more diverse set of leaders in an organization, considering race, ethnicity, gender, caste, and other markers of identity that have historically excluded talent or created “ceilings” for advancement.

This article outlines an approach to investing in future leaders. Through Bridgespan’s work with hundreds of nonprofits over the past decade, we’ve found that the key to leadership development is for managers and staff to work together on a few simple practices:

- Define great leadership by crafting competencies that reflect your organization’s goals and values.

- Co-create professional development plans that build staff skills and capabilities using a 70-20-10 approach—70 percent on-the-job learning, 20 percent coaching and mentoring, and 10 percent formal learning.

- Support consistent development conversations (“check-ins”) between managers and direct reports to put plans into action.

What these practices have in common is a commitment to greater transparency and consistency in developing talent. They complement performance assessment as part of a talent development system and help to build an organizational culture that embraces professional growth. (See “The Difference Between Professional Development and Performance Assessment.”) The nonprofits that put these approaches in place seek to ensure every team member has an opportunity to grow.

Craft Competencies That Reflect Your Organization’s Goals and Values

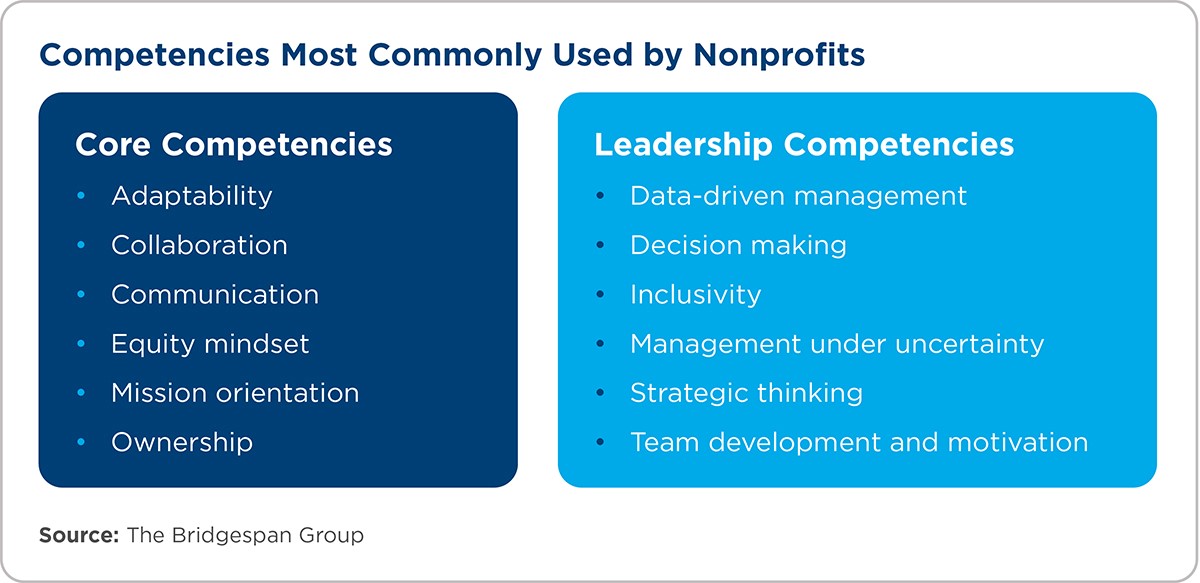

Competencies are the unique set of skills and capabilities that team members need to perform their work today—and prepare for their work to come—to ensure the organization’s future success. Maybe the competencies include “mission orientation” and “team development and motivation,” or perhaps “data-driven management” and “strategic thinking.” Organizations are likely to vary in the unique set of skills and capabilities they each value most. Leaders might identify the organization’s competencies by discussing a few important questions:

- What are the biggest assets of leaders in your organization today? Consider the values, skills, or ways of working that have helped leaders excel in their roles.

- How might leaders in the future need to be different from leaders today or in the past? Consider how your operating context, organizational strategy, and goals may shift over time.

- What are your organization’s values, commitments, or goals related to equity and inclusion? How do your competencies help in furthering those goals and identifying a diverse set of leaders?

The leadership team of Fresh Lifelines for Youth (FLY) asked these questions and more as FLY’s work serving San Francisco Bay Area youth impacted by the juvenile justice system grew. “I saw the urgency of talent development because of the shifts that were coming in the organization,” explains Ali Knight, FLY’s president and CEO. For FLY, as for many organizations’ talent development, the process of deciding which competencies it wanted to focus on was itself valuable. Knight was COO at the time, and talent was one of his responsibilities.

Thinking about competencies was a great opportunity for his team to think about the future of the organization. “What about the culture did we want to keep? What did we want to shift?” he adds. “What do we need in our next group of leaders to set ourselves up for success? The competencies we decided on were the magic of how we develop talent.

"What do we need in our next group of leaders to set ourselves up for success? The competencies we decided on were the magic of how we develop talent."

Competencies manifest as workplace behaviors that can be observed, measured, supported, and developed. Every employee, not just those at the top, requires certain skills and capabilities to succeed in their roles within the organization. But additional competencies are needed for senior leaders and others who are taking on increasingly complex responsibilities. Therefore, many organizations opt to define both core competencies and leadership competencies (an extensive list of sample core and leadership competencies is available on our website):

- Core competencies are those needed by everyone in the organization.

- Leadership competences are those needed in positions of greater leadership, including those involving people management or oversight of complex functions.

The job of investing in future leaders belongs to the executive team—not just the HR department or the executive director. In choosing competencies, FLY brought together five members of its senior leadership team to think through what mattered to them as an organization and define what each competency would look like. They selected competencies such as “cultural sensitivity,” “communication,” and “collaboration.” “These things define what FLY is already doing well, and what we need to make sure everyone does well,” explains Knight.

Then, because it’s not self-evident what something like “cultural sensitivity” means within a particular organization, FLY had to get more specific about each competency. For FLY, cultural sensitivity includes elements like “values diverse identities within the agency” and “self-awareness of bias, power, and privilege dynamics.

Some of the competencies FLY selected, such as “resilience” and “emotional intelligence,” reflect the skills the organization is trying to build in the youth it works with—so staff needed to develop those skills as well. Others, such as “change management” and “team development and motivation,” are focused on the skills that FLY’s leadership team members need to effectively steward the organization and support managers and staff.

Deciding on competencies, and building a leadership development effort around them, makes explicit what is typically implicit in many organizations. It helps employees across the organization know what someone needs to do to succeed. When choosing competencies, articulating what it takes to improve within each competency can help to further clarify them. In addition, it can shift staff mindsets from assessment (“where I am today”) to development (“where I’d like to be next year”).

Defining competencies is also an opportunity to reflect on assumptions that can create inequities. For example, if you are defining what it means to be a “strategic thinker,” you might consider how your definition is influenced by cultural norms that advantage individuals with certain backgrounds or educational experiences over others. In a global organization, for example, are the competencies defined in terms of the cultural norms of the headquarters office, an ocean away from its potential future leaders? If so, that might challenge you to think differently about your competencies—all of them—and about how you articulate what it takes to succeed.

Competencies will change as the organization changes. “Having this framework of competencies helps us think not only about what we need at the moment, but also about what’s next for us a few years on,” says Knight. “So we need to keep thinking—what skills and capabilities have worked for us in the past, and what will we need to do differently in the future?

Co-Create Professional Development Plans Using a 70-20-10 Approach

At Bridgespan, we’ve often asked nonprofit executives, “what experience most contributed to your growth as a leader?” Resoundingly, we hear answers like “that time we launched a new project and I had to really stretch myself” or “that boss who believed in me and coached me through a tough assignment.”

These answers echo research from the Center for Creative Leadership, which gave rise to the 70-20-10 model—which says 70 percent of development should happen through on-the-job opportunities, 20 percent through coaching and mentoring, and 10 percent through formal training. This isn’t a precise ratio, but we find that keeping 70-20-10 in mind is a great way to get better at providing professional development opportunities across the organization.

Using the competencies the organization has identified, staff can work with their managers to create a professional development plan for themselves using the 70-20-10 approach. Although the organization may have identified a dozen competencies, individuals are much better off focusing on one to three competencies at a time, choosing those that are tied to their role and longer-term career goals.

“Our team is good in the technical aspects of the job, but less strong in management,” says Surendra Singh, director of HR and organizational development at the Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation, an Indian NGO that works to facilitate India’s transition to a cleaner energy future. “So we focused on professional development that could build stronger management skills with consistency across the organization. I’ve been in HR 25 years and am finding this 70-20-10 approach to be relevant and effective.”

On-the-job professional development activities don’t need to be large scale, such as a big stretch opportunity or a new project. Look within day-to-day operations to discover where staff can get hands-on experience. Identify actions that are incremental and deliberate—gradual growth that doesn’t overwhelm people with additional responsibilities.

In crafting the on-the-job part of a development plan, staff members and their managers might ask: “Where does this skill show up in our departmental or agency goals?”; “What might be a low-stakes opportunity to practice this skill?”; and “Is there something the manager has been doing for some time that could be delegated to the staff person?” For example, to build a core competency like “communication,” the person could lead a staff meeting on new programming. To build a leadership competency like “project management,” a senior manager could ask a direct report to help create processes to keep teams informed of their own and other teams’ work and deadlines.

And think hard about whether these opportunities are being given out fairly. Research has found that women, for example, often shoulder the burden of less “promotable” extra work (“office housework”), while men more often get high-profile special assignments. Meaningful stretch roles can be scarce resources, and leaders need to make sure they are being thoughtful about who gets those roles and whether this reflects the organization’s equity and diversity goals.

Coaching and mentoring likewise needs to be deliberate. The best coach or mentor isn’t always the manager. It should be someone with the right skills or expertise—maybe even outside the organization. Shakti’s Singh shares an example of how a colleague helped him with one of the goals in his development plan: improving his communication skills. “His communication style was extremely good, and I was impressed. So I asked him if he could help me with my own style. When I was speaking in a forum, he recorded it and gave me comments on how I could improve. I would speak very fast—he helped me speak more slowly. Every two or three months, we’d sit for an hour or two and we’d discuss it.”

In turn, Singh is coaching others on how to improve their client orientation, an important competency at Shakti, where many staff interact frequently with clients. “For example,” he says, “I’m helping them understand that you listen first. You listen for understanding, not just for replying—[to] understand what exactly the client wants.”

Coaching can also happen in groups of peers. New Moms, a nonprofit that supports young moms experiencing poverty and homelessness in the Chicago area, has facilitated quarterly peer-led meetings for staff working on similar competencies. “They were really well received, because they helped people talk about their own progress,” says Laura Zumdahl, president and CEO of New Moms. “People didn’t necessarily feel like they were making much progress on their development plans until they talked with peers. It was really helpful to have that reflective period.” The organization also helped staff connect to people in similar positions at other nonprofits—peer sharing that serves as a type of coaching.

"People didn't necessarily feel like they were making much progress on their development plans until they talked with peers. It was really helpful to have that reflective period."

Formal learning—which can include training or self-study—is typically given far too much emphasis in development plans. We suggest, in line with the Center for Creative Leadership’s 70-20-10 recommendations, that 10 percent is about right. This kind of learning can be more valuable when tied to specific competencies the organization is working on, and when it happens within the organization or otherwise engages a team or cohort, rather than just one or two staff who go off to a training. For example, New Moms has an “expertise in area of focus” competency—and offers internal subject-matter training in areas such as adolescent brain development and motivational interviewing.

Formal learning can be especially important for newer staff or those who will need new technical skills to advance, or staff who need to keep developing their expertise in a particular subject area. You want an accountant who has been trained in current accounting rules, for example, or a clinician who’s up to date on the latest clinical methods.

But formal training is more effective when it is quickly coupled with coaching, mentoring, and on-the-job application, or else the learning could rapidly decay and never be used in a real-world setting. Too often, professional development is thought of as sending someone to a conference—with little thought given to what they are seeking to learn and no follow-up to make sure the learning is applied in their work.

The Difference Between Professional Development and Performance Assessment

Performance assessment and professional development go hand in hand, but they are not the same. Accordingly, the activities that support them are distinct components of a talent management system:- The performance assessment of an individual primarily assesses how well they are doing against agreed-upon goals and targets for the year.

- Professional development—and competency development, specifically—enables performance. Competencies provide a guide for individuals to understand the skills and capabilities they need to develop to improve their performance over time.

Organizations that do this well use the performance-assessment process to identify competencies for each individual to work on. It’s not very helpful to say, for example, “You missed this target, do better.” That can be frustrating for everyone involved. On the other hand, sharing, “By working on this competency, it will help you meet these targets,” is a more constructive way of connecting performance assessment with professional development.

For example, a program manager charged with growing a program over the next few years may need to strengthen competencies like strategic thinking or relationship building to achieve this job goal. Meanwhile, the manager’s performance-assessment goals would more closely align with the growth of the program, such as number of program participants served, partnerships signed, or revenue raised.

Support Consistent Development Check-ins

For many organizations, crafting a set of competencies and creating professional development plans using a 70-20-10 approach will be a new way of formally developing leaders. “Formally” is the key word here. The approach isn’t self-executing, and it needs attention by senior leadership to keep things moving ahead amid the day-to-day pressures of getting the organization’s work done.

To ensure that the whole process ends up being more than just paperwork in a proverbial (or literal) file cabinet, organizations carve out time at least a couple of times a year—and ideally, more often—for managers and each direct report they supervise to have productive conversations about their development.

How often should development conversations occur, and what should they accomplish? We recommend that these development conversations, or “check-ins,” as we sometimes call them, happen at least quarterly. Some prefer a more frequent pacing—like every six weeks—to keep the momentum going. A development check-in should be a two-way conversation in which the manager and direct report reflect on the plan, solve problems that have arisen, and provide feedback to each other on what is going well and how to improve.

Last Mile Health, an NGO that helps develop teams of community and frontline health workers in multiple countries, builds this manager coaching role into how it operates. “Everyone who manages people is assessed on their ability to ensure that staff are growing and succeeding. They are held accountable for developing their people,” says Nathan Hutto, the organization’s COO. Last Mile Health has put into place some operational elements to keep the focus on leadership development. For example, as part of its employee engagement survey, staff members rate their agreement with the following statement: “I believe that my managers care about my development.”

"Everyone who manages people is assessed on their ability to ensure that staff are growing and succeeding. They are held accountable for developing their people."

Managers will need support to become good coaches for their staff’s development. Leadership development is complex because it depends on managers committing to becoming coaches for their team members’ development. Many nonprofits and NGOs treat people development as itself an important leadership competency—elevating its importance within the organization. While there are a variety of coaching styles, if managers are supporting the development of their teams in wildly different ways, an organization can find itself facing serious inequities in the development process. Women, in general, report getting less support from managers—and Black women are even less likely than women of other races and ethnicities to report feeling supported by their managers. Good supervision can also be a challenge. Often, managers shy away from feedback and potentially difficult conversations—avoiding the openness and willingness to give and receive feedback that is central to a good supervisory relationship.

As a result, it can be important to provide training, mentorship, and peer-learning opportunities to help managers become good development coaches and instill a strong leadership development culture within the organization. Last Mile Health, for example, provides training on managing across lines of difference—particularly important given that the organization works in multiple countries and has a very diverse staff. Organizations and individual managers will need to give serious thought—and likely take direct action, as Last Mile Health is—to ensure that bias doesn’t end up distorting the process of developing leaders—making it harder for some people to move forward and driving away some of its top talent.

The executive team should lead by example. If employees and managers are expected to be serious about creating and using 70-20-10 plans, the leadership team should model the same commitment. Members of the leadership team should have their own 70-20-10 plan that they’ve co-created with a manager. When leadership team members share and reference their own development priorities and plans, it sends a message that growth is important, there’s no stigma around development planning, and it’s worth dedicating time to development.

"It's easy for people to say I don't have time...to support leadership development. But my direct reports saw me doing it, so it was hard for them to say they didn't have the time to do it, too."

“It’s easy for people to say I don’t have time to do the supervision and the other things needed to support leadership development,” says Michelle Yanche, CEO of Good Shepherd Services, which supports youth and family members in struggling neighborhoods throughout New York City. “But my direct reports saw me doing it, so it was hard for them to say they didn’t have the time to do it, too.”

When an organization’s top leaders model vulnerability—the idea that everyone, no matter their level or seniority, is still working to develop and improve—it can send a powerful message across the organization and create a sense of psychological safety for others to do the same.

• • •

The work of investing in future leaders is vital to most organizations’ futures and the missions they pursue. At its best, this investment supports a virtuous cycle—people of all backgrounds become better at their jobs, they are more likely to stay with their organization when they see and experience growth, and organizations with great talent are able to push a more inclusive organization forward in pursuing its mission.

In addition, with the reality of turnover in any job market, the ripple effects of investing in future leaders extend beyond an organization. “Our investment in talent is for our organization, but it’s also for our people,” FLY’s Knight explains. “If people leave here, they’ll have more opportunities to serve because of the skills they were able to develop with us. Putting the organizational hat aside, we are helping build servants of the movement, warriors for justice.”

Our “Nonprofit Leadership Development Toolkit” can help you jump-start your own leadership development process. It has ready-to-use templates and resources, including sample competencies drawn from our competency bank, a 70-20-10 development plan template, and more. It also provides guidance on rolling out and implementing this approach to investing in future leaders in your organization’s systems and culture.

The authors thank Barbara Christiansen, whose insights from her experiences as a former Bridgespan consultant and continuing work as a coach with Bridgespan’s Leadership Accelerator program deeply shaped this article.

Download the Nonprofit Leadership Development Toolkit

Please fill out the form below to receive a download link to the Nonprofit Leadership Development Toolkit. Bridgespan uses the information we receive through these forms to better understand the audience for our work and to inform our funders more thoroughly about the impact of our knowledge efforts. We do not share your personal information with anyone outside of Bridgespan. All data we provide to funders is aggregated and does not include any personally identifiable information.

If you would rather not fill out the form, you can download the PDF file directly. Thank you!