Large nonprofits with broad networks that have been serving communities for decades have the reach and capacity to take on big social issues and create impact at scale. That's a good thing at a time when a broad range of social, health, and environmental challenges threaten to outpace society's ability to solve them. Still, an organization's greatest strength can also be its greatest weakness. In the case of nonprofit networks, size, reach, and complexity may also threaten to slow reaction time or nimbleness during periods calling for greater flexibility in decision making.

This PowerPoint presentation highlights research conducted for this article and shares key practices used by 11 large network boards. Click here to download >>

Recently, The Bridgespan Group assessed the boards of 11 large network organizations—five voluntary health agencies (VHAs) and six other large network nonprofits.1 We looked beyond their boards' core responsibilities of governance and talent development to examine how they are refining and retooling their own structures, compositions, and procedures to become higher-performing partners to their organizations.

Our findings confirmed some of our expectations but also unearthed surprises, such as the use of longer board chair tenures to smooth transitions, more frequent use of staff time to manage board members' expectations, and efforts to recruit millennials. Our findings provide practical insights for any nonprofit board seeking to more effectively help an organization achieve social impact.

Getting smaller and focusing on skills to be more nimble

While it is difficult to determine a single best size for network boards—one allowing them to enjoy diverse skill sets while remaining flexible and efficient—most of the networks surveyed have been reducing their size to roughly 20 to 30 members. The few exceptions tended to be boards, such as the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, that are required to reflect their affiliates' large geographic representation.

In general, skillsets, such as financial management and relevant operating experience seem to be overtaking geographic representation as a priority. All the organizations profiled use a board skills/composition matrix (for an example, see this matrix from BoardSource) to readily identify and fill critical skills gaps across the board. Some organizations have even opted to use a matrix in place of hard and fast rules on representation. For example, one organization recently dropped the last vestige of its representation requirement reasoning, "We'll always have that expertise on the board, but we want to have maximum flexibility in selecting the right folks."

Skills turning up routinely in the matrices included experience in a particular field or industry (e.g., medical field for VHAs), leadership experience, professional skills (e.g., legal, finance), political balance, and fundraising ability. (Leaders noted that organizations also could ensure that their boards continue to have a local perspective by considering geography or chapter experience in their matrices.)

Strengthening board leadership with longer terms and forward thinking

Given the need for the board chair to drive agenda setting, several organizations have increased their chairs' term lengths, typically from one year to two or even three years. Longer terms, said one leader, allow the chair to have time to help drive needed improvements in board responsibilities and management support. "We are a complex, diverse organization," he said. "It takes time to get to know us well, especially if you are responsible for leading the organization."

Chair terms are not only getting longer, organizations are also overlapping them with one another to streamline transitions as new leadership gets up to speed. Most chairs understand that they will step into the role at least one year in advance and may stay for at least one year after their terms are up (as the immediate past chair). As one board chair put it, "That way you have a year to learn while the current chair is still serving."

Almost every network has a nominating committee responsible for the process of recruiting new board members, but increasingly the actual recruiting is the responsibility of the board chair and CEO. To get the best talent for the future, they aren't just recruiting to fill open spots, they're looking at their needs two-plus years out. Similarly, the identification of the next board chair has moved from the nominating committee to a tighter group including the current board chair, an immediate past board chair, and the head of the nominating committee, with the CEO providing active input. According to one board chair, "Until you have been chair, you can't really know the full scope of the job and who will be best qualified to help move the organization forward."

Changing board composition to reflect changes in America

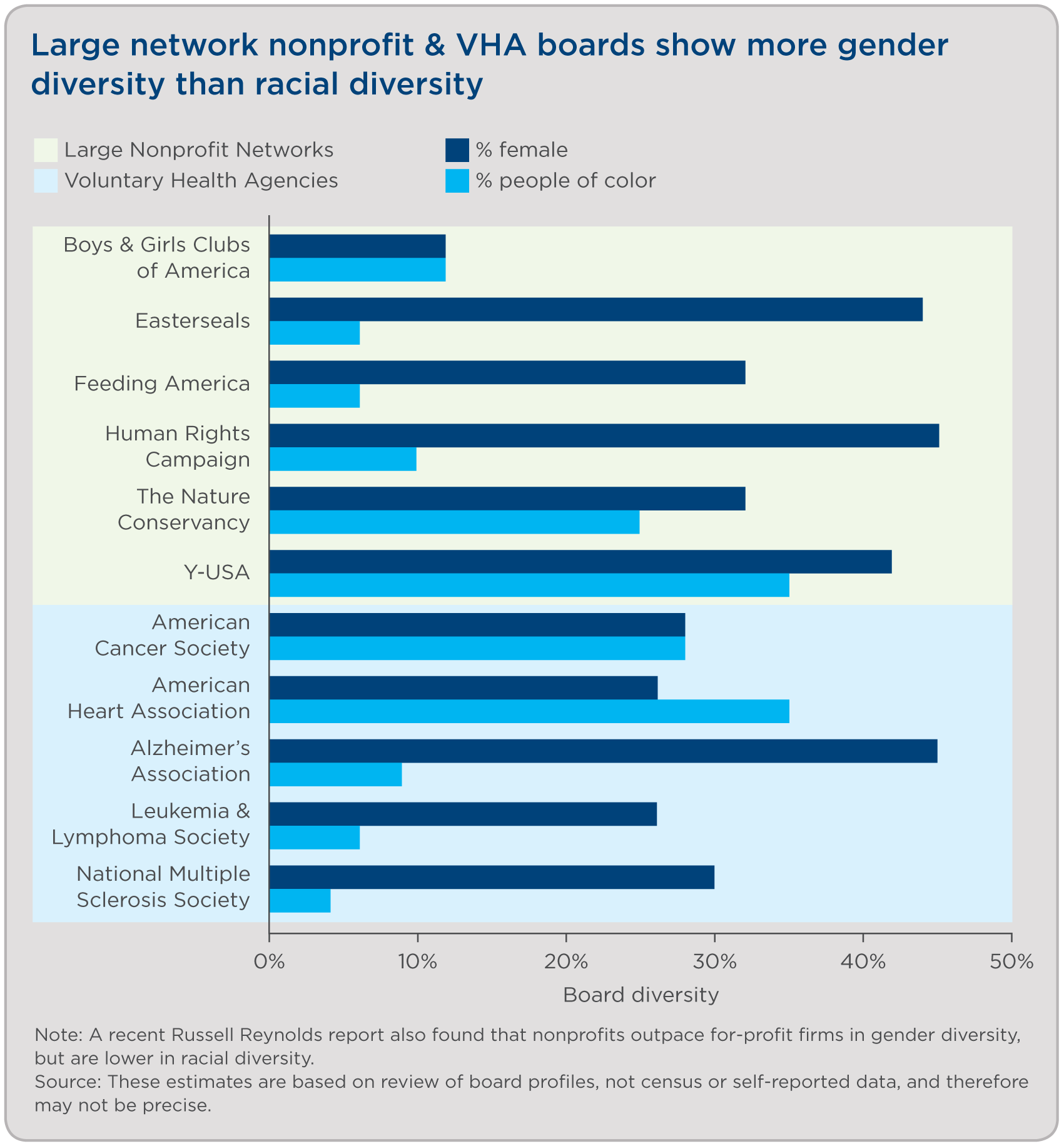

As America is becoming increasingly diverse, the network boards we studied are following suit, but with mixed success. Earlier this year, a report from Russell Reynolds2 noted that nonprofit boards of large organizations generally do better than the private sector on gender diversity and worse on racial diversity. Our research confirmed these findings; however, we also discovered significant progress among some organizations that have made a persistent effort over many years.

The following chart shows the relative strength in achieving gender diversity and the struggles of achieving ethnic diversity. Through years of effort, organizations like the YMCA of the USA, American Heart Association, and American Cancer Society have recruited over 30 percent of their board members from diverse ethnicities, but for others the challenge remains. The network boards we surveyed typically strive to become more diverse, yet find that their ability to tap the pool of proven, diverse leaders for board members hasn't kept pace with changing American demographics.

Beyond gender and ethnic diversity, we were surprised to learn from at least four of the organizations we spoke to of a new focus on age as a targeted characteristic, especially around the recruitment of millennials. While there is a desire to recruit from this large and highly influential population (born between 1982 and 2004), millennials are "super busy building their careers" and not yet financially viable candidates for organizations with a give/get requirement for board membership. Still, organizations reported they "remain hopeful, and are taking steps to reach out to" them. In some cases, organizations have added the desire to recruit millennials to their board skills/composition matrices.

Using committees to free up board time to focus on strategy

A lot has been written on the importance of minimizing the number of committees, so we expected to see fewer committees among large network nonprofits. Instead the organizations we profiled generally had eight to 12 committees each;3 only one had reduced the number significantly during the past year. Leadership explained the discrepancy by noting committees are "where the heavy lifting happens" in terms of necessary governance and compliance responsibilities, freeing the full board to focus on the more strategic and generative aspects of board work during board meetings.

Additionally, several organizations have implemented tactics to keep committee work firmly in its proper perspective. These include:

- Delegating compliance-focused decision making to a committee to ensure that the board considers only mission critical issues;

- Encouraging committees to work together to streamline problem-solving; and

- Utilizing an online protected portal (rather than meeting time) for document and information sharing.

Dedicating staff time to bridge the gap between meetings

It takes a lot of effort between meetings to keep boards focused on mission-critical issues during meetings. Some organizations have dedicated a staff person to provide the board with full-time project management and facilitation support in order to help shape agendas, keep the board and its committees on track, and ensure appropriate follow-up.

Typically, this agile professional carries out two charges. First, he or she manages the oft-overlooked task of a board's "care and feeding," beginning with helping on-board new members and having regular check-ins with each member throughout his or her service. Second, he or she sends out talking points or an after-action report to document decisions and next steps, and gives board members a common message to share with their constituents. While most boards send out post-meeting surveys, the facilitator/project manager can add significant value by conferring one-on-one with each board member about his or her goals and expectations.

Conclusion

Tackling today's social issues requires organizations of all sizes to adapt their approaches and to think differently about the impact they seek. The evidence we've gathered around large network boards provides insight into how to do so. By making themselves leaner and more flexible, maximizing productivity, and recruiting with today's and tomorrow's needs in mind, large network boards are purposely reshaping themselves for a future as more effective and important partners in their organizations' efforts to address critical social needs.

Alan Tuck is a senior advisor to The Bridgespan Group. Taz Hussein is a partner in the Boston office and head of the Public Health practice at Bridgespan. Rose Martin is a former Bridgespan consultant.

Sources used in this article

1. The organizations we interviewed include: Alzheimer's Association, American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Easterseals, Feeding America, Human Rights Campaign, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, The Nature Conservancy, and the YMCA of the USA.

2. Who sits at the boardroom table? A look inside nonprofit boards, Russell Reynolds Associates, January 24, 2017.

3. This includes standing (required in the organization's by-laws) and additional committees.