Asian philanthropists view collaboration with government as a necessary and desirable path to achieving social and environmental change at scale. Yet collaboration can take many different forms. To gain insights from those with experience, The Bridgespan Group interviewed more than 20 philanthropists and social-sector leaders across a number of Asian countries as part of the research that led to our companion article, “The Philanthropic Potential of Asia’s Rising Wealth.”

Many philanthropists’ first instinct when working with the public sector is to fund a pilot programme. The idea is compelling: support an idea with unproven potential, and, if successful, seek government support to move from pilot to wide application. Philanthropic capital is better suited than public funding for experimenting, risk taking, and adopting the learning mindset that allows a demonstration to break new ground and make adjustments along the way.

“Philanthropists from the private sector know a lot about business, but not as much about the issues they want to work on,” says Jemmy Chayadi, director of strategy and sustainable development at the Djarum Foundation in Indonesia. “Piloting is an important upfront investment to learn about and monitor results in new areas and to manage expectations on what can be accomplished in a certain period of time.”

As we dug deeper, though, we heard several other approaches to, and observations about, working with government. By summarising them below, we hope it will help guide others as they begin or expand their philanthropic journeys.

Structuring Philanthropic Partnerships with Government

Philanthropists we spoke with characterised five ways in which they approach social-impact relationships with government. Relationships often display two or more of these characteristics at the same time.

1. Support government priorities

Some philanthropists adjust their impact goals and solutions to align with government policies, priorities, or programmes. This approach is a relatively easy entry point to begin developing a relationship and track record with government, especially for philanthropists new to public-sector collaboration.

The Tanoto Foundation exemplifies efforts to bolster existing government priorities. In 2017, the foundation partnered with the Indonesian government in making a reduction in childhood stunting rates a national priority. At the time, the national stunting rate was above 30 percent. The foundation was already doing a lot of work with Indonesian schools and teachers, but it realised that much of its effort would be for naught if kids entered school cognitively delayed because of stunting. “A lot of what we do is really piggybacking on the big environment, aligning with government policies,” Belinda Tanoto, daughter of the foundation’s founder and a member of the foundation’s Board of Trustees, told Alliance magazine.1 “So our role there becomes catalytic, enabling different resources to come together.”

"A lot of what we do is really piggybacking on the big environment, aligning with government policies. So our role there becomes catalytic, enabling different resources to come together."

For example, the Tanoto Foundation joined with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as a founding donor to the World Bank Multi Donor Trust Fund for Indonesia Human Capital Acceleration, activating a US$400 million World Bank performance-based loan to the Indonesian government. The loan ultimately catalysed billions of dollars from the Indonesian government for reducing stunting. To help close a data gap, Tanoto funded research on stunting through partnerships with institutions like Alive & Thrive and the SMERU Research Institute. It also partnered with the World Bank to publish a dashboard with key metrics that serves as a central database across 23 Indonesian government ministries and agencies to better target and coordinate stunting programmes. In addition, Tanoto convenes key funder and social-sector stakeholders and encourages them to work with the Indonesian government to continue progress on the programme’s goals.

The foundation’s support has contributed to a decline of stunting nationally, falling from 31 percent in 2018 to 22 percent in 2022. Today, the foundation continues to assist the Indonesian government in working towards its target of 14 percent by 2024.2

YTL Foundation follows a similar path in its work to elevate educational standards across Malaysia. The foundation aligned its programmes for improving public school infrastructure and developing a more holistic student learning experience with the Ministry of Education’s Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025. “Collaboration with the government, fostered by mutual understanding, is necessary,” says YTL Foundation Programme Director Dato’ Kathleen Chew.

2. Collaborate at multiple levels

Philanthropists we spoke with were deliberate about choosing which level or levels of government to work with. Some collaborate on the local level, where they can support how government policy is implemented in, for example, a school district or a hospital. Others look for opportunities at the provincial or national levels to scale successful programmes and influence policy and priorities.

"Many high-impact philanthropists work across levels — including national to local governments, senior to mid-level public employees, and across agencies or ministries — to achieve sustained change."

And many high-impact philanthropists work across levels — including national to local governments, senior to mid-level public employees, and across agencies or ministries — to achieve sustained change.

They take time up front to figure out who in government to work with. For example, an education programme may require more than just a ministry of education’s buy-in. It may also need provincial or local government approval, along with a budget allocation from the ministry of finance.

Whilst getting the senior-most leader’s support is critical, effective implementation often requires working with frontline civil servants who carry out day-to-day functions. “Active engagement with policymakers at all levels can be a key determinant of long-term success and ultimately is the only way to achieve impact at scale,” advises AVPN, a funders’ network based in Singapore.3

Many philanthropists act as convenors to bring together different participants from the public, private, and social sectors to work on an issue of mutual concern. Such gatherings build on existing relationships and help align all parties on shared goals.

Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust’s Career and Life Adventure Planning Programme, or CLAP@JC, demonstrates the value of collaboration at multiple levels. CLAP@JC is a decade-long effort that aims to transform the conventional life-planning service model — which typically operates in an educational setting with the goal of facilitating job seeking — to operating at an ecosystem level whilst advocating for broadened definitions of talent, work, and success. This model aims to support a paradigm shift of practice across education, community youth services, and the workplace to smooth the school-to-work transition. To uplift the industry standard, and with the ultimate goal of achieving meaningful engagement in life and work, CLAP@JC has systematised this approach in creating its Hong Kong Benchmarks for Career and Life Development (CLD), which support young people from diverse backgrounds in developing the competence, agency, and aspiration to explore multiple pathways that align with their own values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge.

In practice, the programme operates in both school and community youth-service settings, providing systematic guidance in a range of areas — from developing CLD policy, provision of professional training, advocating for youth co-creation activities, integrating workplace competence into learning, and parental engagement to providing multiple pathways to information as well as meaningful encounters with tertiary institutions and workplaces. Two roles in the programme, in particular — “Community Connectors” and “Enterprise Advisors” — bridge gaps between schools, communities, and workplaces. Thus far, CLAP has successfully incorporated a third (150) of local secondary schools, 115 nonprofit youth-service units, and 3,700 employers into its network. One critical strategy for creating a sustainable ecosystem for this work is the programme’s close partnerships with Hong Kong government bureaus (Education, Labour and Welfare, Home and Youth Affairs, and Security).

The results have been encouraging. Some 30,000 students and 13,000 out-of-school youths have benefitted. Most students who participated (89 percent) showed clear direction and have taken action to pursue their plans; 82 percent of those not in school or not currently employed have made meaningful progress, including pursuing further studies and entering the workplace with a greater sense of hope and greater earning power than a comparison group. Ninety percent of youth participating in CLAP’s pre-employment training programme also transitioned smoothly into jobs that were originally intended only for university graduates.

Circle of Care in Singapore, a joint initiative of the Lien Foundation, the QuantEdge Foundation, and Care Corner Singapore (a nonprofit), launched a decade ago and brings together partners across the public, private, and social sectors to help preschool children in Singapore thrive and grow. Partners include government preschools and primary schools, along with researchers at several private firms and academic institutions.

The programme is grounded in evidence-based practices and taps the latest research in neuroscience, social work, and early childhood to ensure best outcomes for children and families. A recent study found that Circle of Care’s integrated preschool-based healthcare model for low-income families reduces barriers to health services and improves overall quality of life for children who participate.4

3. Invest in long-term relationships

Just as in business, relationships in philanthropic pursuits are important to getting things done. Philanthropists work to understand the roles, agendas, and interests of the civil servants they work with. They also strive to build trust by convincing government officials of their sincerity and credibility. One foundation leader put it this way: “Building personal relationships is very important in the Philippines, and it takes time. It’s an investment. We host events to get to know public-sector leaders, like a speaker series with members of local government.”

"Building personal relationships is very important in the Philippines, and it takes time. It’s an investment. We host events to get to know public-sector leaders, like a speaker series with members of local government."

Philanthropists we interviewed advised not focusing solely on individual relationships, which can come and go. “It’s important to build institutional relationships,” observes a foundation leader. “Our relationship is with the ministry, not the minister.” We also heard the value of patience. Getting things done in the social sector can take much longer than in the business world, making it important to plan accordingly.

Cherie Nursalim, executive director of GITI Group, a conglomerate based in Singapore, exemplifies relationship building as she pursues tri-sector collaboration. She has encouraged representatives of various private businesses and government bodies to join the boards of the Institute for Philanthropy at Tsinghua University in China and the United in Diversity Foundation, which she co-founded. Nursalim sees strong relationships amongst leaders in business, government. and civil society as necessary for creating sustainable solutions to some of the region’s biggest challenges.5

4. Design with government constraints in mind

Governments operate with budget, organisational, and operational constraints. Philanthropists told us that they increase their prospects for success by identifying constraints early and then designing approaches with them in mind. Often, it can be more effective to support the government in improving an existing programme instead of developing a new one. Some advised that it is especially helpful to have a public-sector representative participating from the start, even if informally, to guide how to best fulfill government expectations. This can also help build a sense of public-sector ownership from the beginning.

Yayasan Hasanah, the foundation of Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund, demonstrates how funders work within government budget constraints. Hasanah incubated and funds the nonprofit Yayasan AMIR, which jointly manages the Trust Schools programme under the umbrella of the Ministry of Education. Hasanah designed Trust Schools to work within existing school budget allocations with school principals running the operations. From the start, Hasanah collaborated with education officials to build buy-in and ownership of the programme in preparation for when Yayasan AMIR eventually exits.6

The programme, which started as a pilot in 10 schools before expanding, works with school leaders, teachers, students, and parents to improve student learning. It provides leadership training, promotes parent and community involvement, and gathers funds from public and private sources to support the programme.

In a 2018 impact study, 80 percent of students reported a positive experience with their Trust School, and 90 percent reported experiencing positive educational outcomes. The schools have also seen significant improvement in the quality of school leadership and management and engagement from parents and communities. In 2021, the programme served 94 schools across 11 states, reaching roughly 74,185 students and involving 5,350 teachers.7

The Philippines-based Jollibee Group Foundation launched the Busog Lusog Talino (BLT) school feeding programme in 2007 in support of the government’s efforts to enhance nutrition amongst undernourished school students. The BLT programme improved on existing kitchen construction and food preparation techniques with lower-cost alternatives and works with local partners to ensure it runs in a consistent, cost-effective manner.

In 2016, the Department of Education expanded the programme across the Philippines, adopting the foundation’s cost-conscious kitchen and food preparation innovations.8 This coordinated effort between the Jollibee Group Foundation and the government has led to a reduction of wasting and absenteeism amongst undernourished students.9

5. Seek to embed desired changes

Philanthropists can work to ensure their efforts endure by embedding them within government systems. One way to do so is to work with local-level civil servants, who typically have more longevity than politically appointed leaders. “We usually start with the local government because we already know them well; they’re practically our neighbours,” says one foundation official. “We have a good understanding of the political processes and how we can best work together.”

"We usually start with the local government because we already know them well; they’re practically our neighbours. We have a good understanding of the political processes and how we can best work together."

The Knowledge Channel Foundation in the Philippines has successfully used a different approach. It “locks in” government collaboration by periodically signing a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Education. Led by Rina Lopez, whose family owns a conglomerate involved in media, real estate, energy, and manufacturing, the foundation has worked with the Department of Education for more than two decades, forging relationships with 10 department secretaries. The memorandums of understanding detail what aspects of education department strategy the foundation will support over the coming years. For example, in 2020, the foundation provided multimedia educational resources to five million students in over 8,000 public schools.10

The Zuellig Family Foundation works across multiple layers of the government in the Philippines — from Department of Health officials at the national level to governors and mayors at the municipal level — to implement its “Health Change Model” to respond to the health needs of rural communities. The model provides local leaders with a comprehensive capacity-building programme involving training, practicum, and coaching. This approach helps to ensure the programme’s sustainability.

Through its partnership with various levels of government, the foundation has successfully reduced teenage pregnancy by half between 2018 and 2021 in Cagayan de Oro City and reduced stunting prevalence in Sarangani by a similar margin between 2019 and 2021.11

Some philanthropists continue to support government efforts after it takes ownership of a programme. They accomplish this by funding capacity building within the relevant government agencies to ensure they can implement change. They may also fund research to track a programme’s effectiveness and identify potential areas of improvement or provide technical assistance to support effective implementation.

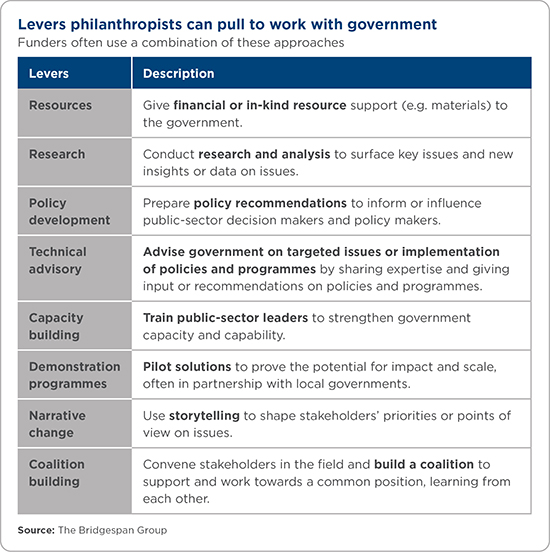

Levers Funders Can Pull

When we look at the various ways philanthropists partner with government, we also see a number of recurring approaches, distilled in the chart below. We think of them as levers philanthropists may pull in pursuit of their goals. Successful collaborations with government typically involve multiple levers. How many to pull and when depends on the context in which a philanthropist is working.

* * *

Whilst collaboration with government is a popular way to expand and sustain effective programmes, for a variety reasons, it is not always the best approach. Alignment with government priorities can limit the degree and pace of change achievable. Government may not have the capacity, or perhaps even the technical skills, needed to develop and implement a particular programme. Given the multiple competing priorities of government, slower decision making may risk stretching out timelines. And in some instances, concerns about government corruption and potential reputational risks cause philanthropists to look for other avenues to achieve their goals. For example, many prefer to make grants to nonprofits that may themselves engage with the government as a part of their own efforts to create change.

Whilst collaboration with government is a popular way to expand and sustain effective programmes, for a variety reasons, it is not always the best approach. Alignment with government priorities can limit the degree and pace of change achievable. Government may not have the capacity, or perhaps even the technical skills, needed to develop and implement a particular programme. Given the multiple competing priorities of government, slower decision making may risk stretching out timelines. And in some instances, concerns about government corruption and potential reputational risks cause philanthropists to look for other avenues to achieve their goals. For example, many prefer to make grants to nonprofits that may themselves engage with the government as a part of their own efforts to create change.

Still, collaboration with government remains popular. For most philanthropists, the advantages — and the need and urgency to act — outweigh the challenges and offer multiple ways forward. As one foundation leader put it: “The issues and problems that society needs to tackle are so big that oftentimes people who want to help, don’t, because they can’t figure out how to narrow these problems down into bite-sized chunks to start.” Our hope is that we have provided enough examples of “bite-sized chunks” for philanthropists on the sidelines to get in the game.

The authors are grateful for the indispensable help of Jenn Kozyra, manager, and Hui Chen, associate consultant, in Bridgespan’s Singapore office.