Key Takeaways

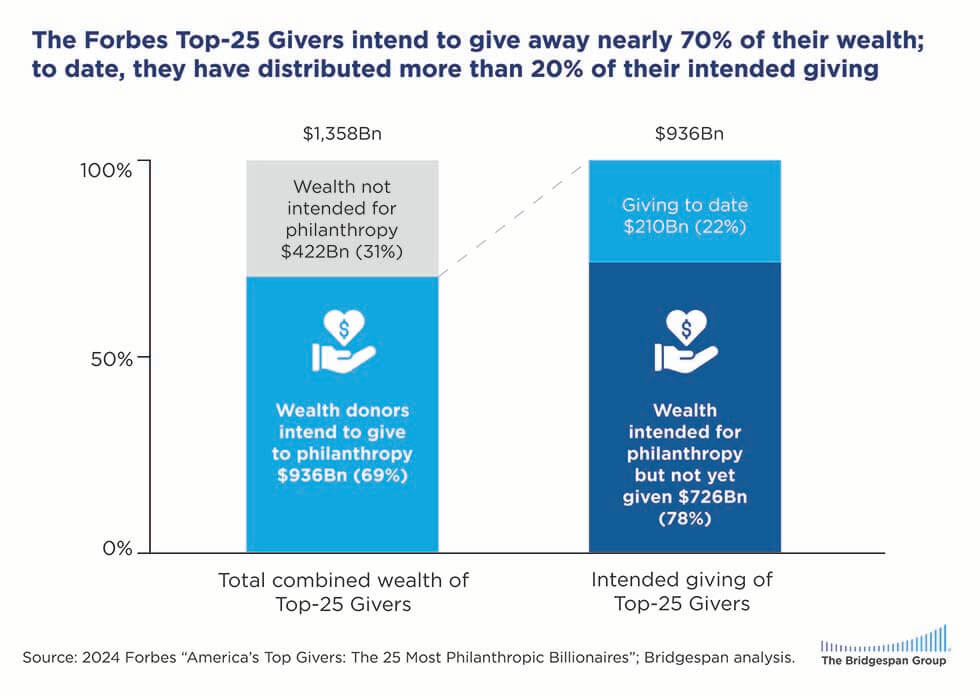

- Finding 1. About half of America’s 25 most generous givers have already given away more than 20 percent of their wealth and have stated aspirations to give much more—a $720 billion opportunity.

- Finding 2. The largest foundations in the United States—the traditional philanthropic vehicle of choice for American philanthropists—show declining commitment to spending down.

- Finding 3. There are more small- to mid-size foundations that decide to spend down than larger foundations, a decision made by both principal donors and successor trustees.

- Finding 4. The most generous givers are using multiple giving vehicles rather than relying solely on private foundations to get dollars out the door quickly.

Even as the wealthiest Americans accumulate new levels of wealth, some have famously committed to donating at a significant scale. As one example, since 2010, more than 240 billionaires worldwide—or nearly 10 percent of the billionaires tracked by Forbes globally as of 2024—have signed the Giving Pledge, committing to distribute at least half of their wealth upon their death.

Among the most recent signers is Jahm Najafi, an international investor, whose Giving Pledge statement reflected the motivations of many large givers: “to live with purpose, to give back to those I love and the world we inhabit.”

That intent leads to the two questions that animate this research brief: Are donors’ intentions to spend down their assets translating to action? And, if so, how?

The traditional way to answer these questions would be to analyze private foundations: for a century, the foundation reigned as a primary legal vehicle for distributing charitable assets. A decade ago, our analysis of the 50 largest foundations in the United States found that an increasing number were choosing to spend down their assets rather than continue to endow them in perpetuity. We call them “spend-down foundations.”

Many donors continue to give primarily through foundations.1 A 2024 report by Altrata suggested that nearly 30 percent of individuals with a net worth greater than $100 million have a private foundation.2 And some individuals still choose to spend down these assets. A 2020 New York Times article built on a study by Rockefeller Advisors and Campden Wealth reported that spend-down foundations were on the rise. A 2020 article by Katie Smith Milway and William Galligan in Stanford Social Innovation Review found that 27 of the top 50 foundations were incorporated in perpetuity—suggesting that the remainder had substantial flexibility in deciding whether to spend down.

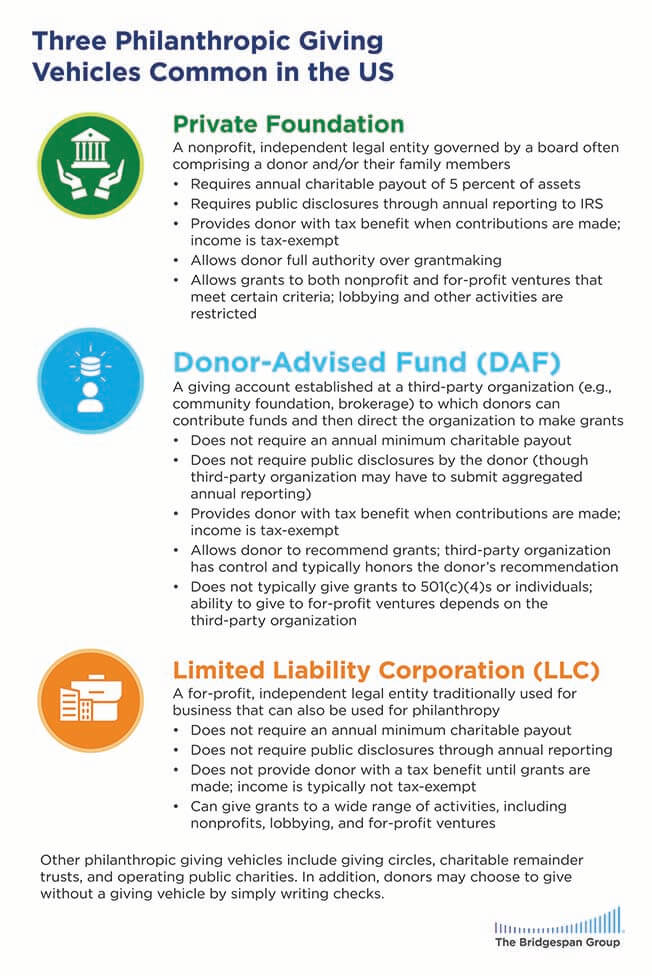

But today, the most generous donors increasingly deploy a range of giving vehicles, such as donor-advised funds (DAFs) and limited liability corporations (LLCs). DAFs are relatively young philanthropic vehicles that have grown in popularity significantly in the past decade. A DAF is an account established at a public charity that allows donors to make a contribution, to receive an immediate tax deduction, and to prompt the charity to make grants from the account over time. Donors at a wide range of income levels, not just high-net-worth individuals, use DAFs.3 Some donors use a DAF as their primary giving vehicle, while others use it to complement a foundation and/or an LLC.4 The 2024 National Study on Donor Advised Funds suggests that the number of DAFs has increased more than fivefold from 2010 to 2020.5 In contrast, the number of private foundations has grown at a far slower rate, according to Internal Revenue Service records, inching up 11 percent over the same period.6

Growth in giving appears to be catching up to the growth in the number of DAFs: the rate of payout from DAFs is on the rise, with a median payout rate of 9 percent, according to the same report.7 In contrast, only 11 percent of private foundations in a Candid survey report paying out over 9 percent of assets in 2023.8 In addition, many donors make use of DAFs serially, adding funds to the account, spending balances down by making grants, and then adding funds to begin the cycle again. What’s more, the value of grants made by DAFs was approximately half of the value of grants made from private foundations in 2022.9 If DAFs continue on the trajectory they have been on in recent years, grantmaking from DAFs will exceed that of foundations by 2029.

Growth in giving appears to be catching up to the growth in the number of DAFs: the rate of payout from DAFs is on the rise, with a median payout rate of 9 percent, according to the same report.7 In contrast, only 11 percent of private foundations in a Candid survey report paying out over 9 percent of assets in 2023.8 In addition, many donors make use of DAFs serially, adding funds to the account, spending balances down by making grants, and then adding funds to begin the cycle again. What’s more, the value of grants made by DAFs was approximately half of the value of grants made from private foundations in 2022.9 If DAFs continue on the trajectory they have been on in recent years, grantmaking from DAFs will exceed that of foundations by 2029.

Another giving vehicle has stepped onto the stage over the past decade: the philanthropic limited liability corporation (LLC). Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, is often cited as the first donor to use this vehicle for giving at a large scale when he created an LLC as part of the Omidyar Network in 2004. The use of philanthropic LLCs picked up steam after Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg publicly launched the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and an associated LLC in 2015. Since then, an increasing number of wealthy donors have turned to LLCs to house their philanthropic activity.10 LLCs provide donors with several benefits including anonymity, flexibility, and integration with their family offices.11 Given that LLCs are not required to report on their activities publicly, however, there is limited public data on the prevalence of LLCs and how they are used by donors.

Giving while living is clearly no longer synonymous with spending down a private foundation. From our own advisory work and conversations with other advisors, we have also observed an uptick in interest in giving while living in the field. So, our team wanted to piece together a more complete picture of trends in giving vehicles, combining analysis of direct giving by the country’s most generous givers with trends from traditional foundation giving. Given the limits of the data that is publicly available, this research brief paints only a partial picture of trends in giving. It looks at trends in the sector broadly—across a range of vehicles and wealth levels of donors. We caution against drawing too many conclusions as the trends are still evolving, but we hope it provides a step toward better understanding the shifts underway and, in turn, raises questions that will help the social sector understand how this new range of vehicles can meet donors’ giving goals.

Finding 1. About half of America’s 25 most generous givers have already given away more than 20 percent of their wealth and have stated aspirations to give much more—a $720 billion opportunity.

Our new analysis of the 2024 Forbes “America’s Top Givers: The 25 Most Philanthropic Billionaires” list reveals that, even as some have gotten much wealthier in recent years, these 25 donors have collectively donated 16 percent of their current wealth. What’s more, three of them have donated more than half their current wealth—and almost half have donated more than 20 percent of their current wealth.

Some have spent many years reaching this level of giving. For example, Amos and Barbara Hostetter have given away approximately a third ($1.6 billion) of their wealth in the years since they made their fortune on cable TV in the 1990s—with a focus on climate, the arts, and education in Massachusetts. Others, like MacKenzie Scott, have given away a substantial share of their wealth very quickly.12

However, there remains a significant gap between stated aspirations and actual giving.

Among these Top-25 Givers, 60 percent have, through public statements, signaled an intent to give away all or nearly all of their wealth. Still, with a few notable exceptions, donors report that it is difficult to distribute resources as fast as they would like. Moreover, many are much, much wealthier now than they were just a few years ago, making it a steeper climb to fulfill their philanthropic ambitions. We see this trend play out in giving at large: over the past few years growth in assets has continued to outpace giving. According to our analysis, American families with over $500 million in assets donated just 1.2 to 1.3 percent of their assets to charity in 2023, compared to the S&P 500’s 20-year average annual total return of over 9 percent.

Consider this intriguing thought experiment: if the 15 most generous givers who have already signaled an intent to give away all or nearly all of their wealth followed through, an additional $720 billion of private wealth would be unlocked for the common good. Even if these donors collectively reached a lower goal of matching their peers who have given away 20 percent in a decade, about $70 billion in new money would flow back to society in that time.

Finding 2. The largest foundations in the United States—the traditional philanthropic vehicle of choice for American philanthropists—show declining commitment to spending down.

There is an aspiration among some of the wealthiest givers to give away a substantial portion of their assets in their lifetimes—and one way has been through spend-down foundations. In 2013, our research identified four of the 50 largest US-based foundations as spend-downs: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, and Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation. In our new analysis of the 2023 Top-50 Foundations list, however, the Gates Foundation is now the only one for which we could find a public commitment to spend down. Atlantic Philanthropies successfully spent down its endowment, and the other two foundations have fallen out of the Top-50 Foundations.13 Moreover, not one of the 17 foundations new to the Top-50 Foundations list in the past decade has publicly committed to spending down.

In parallel, consider the Forbes Top-25 Givers list. (Bear with us here: we reference separate analyses of the Top-25 Givers and the Top-50 Foundations, and our own list of 52 spend-down foundations throughout this article.) Only three of those on the 2024 list have been giving primarily through a spend-down foundation—Bill and Melinda Gates, Warren Buffett, and Eli and Edythe Broad, all of whom have been using that mechanism for quite a while. In July 2024, Warren Buffett told The Wall Street Journal that instead of giving his remaining fortune (currently estimated at $143 billion) to the Gates Foundation, as previously expected, the money will go to his children through a charitable trust.

The Top-50 Foundations are big names in US philanthropy yet control a minority of the assets. We estimate that collectively their endowments total less than a third of all assets held by foundations in the United States. This led us to two more questions: First, if the Top-50 Foundations aren’t spending down, which foundations are? And second, if the Top-25 Givers are not giving big primarily through spend-down foundations, how are they doing it?

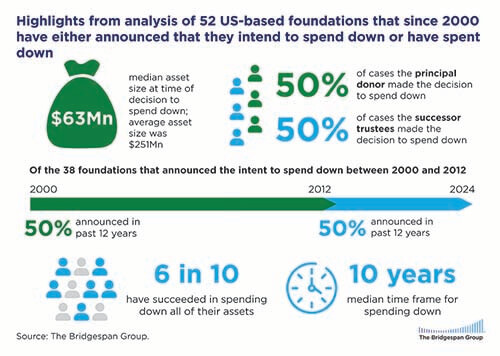

Finding 3. There are more small- to mid-size foundations that decide to spend down than larger foundations, a decision made by both principal donors and successor trustees.

While public commitments to spend down are declining among the Top-50 Foundations and Top-25 Givers, a wide range of foundations at lower asset levels are still deciding to do so. This is not surprising, given that we often hear from donors that it is easier to spend down a smaller endowment.

To understand this trend, we compiled and analyzed a new list of 52 US-based foundations that since 2000 have either announced that they have made commitments to spending down or have spent down—or both. (One important caveat: since our list was compiled from public commitment statements, it does not represent all foundations that have made this decision, because some may have chosen not to publicize it.)

Click here to download a PDF of the above.Here are some of the highlights:

Click here to download a PDF of the above.Here are some of the highlights:

- The median asset size of the 52 foundations at the time of the spend-down decision was about $63 million. The average asset size was $251 million, skewed by a few very large foundations. In other words, the overall trend appears to be that smaller foundations are making this decision rather than those on the Top-50 Foundations list.

- The overall trend toward spend-down foundations appears steady. Of these 52 foundations that have announced their intention to spend down since 2000, 50 percent announced between 2000 and 2012; 50 percent have announced in the past 12 years.

- In about half of the spend-down foundation examples, the principal donor made the decision to spend down; in the other half, successor trustees made the call. When the principal donor made the decision, it happened either during their lifetime or based on their stated wishes about what should happen after their death. In the other half of cases, trustees led the decision, with a significant number of these spend-down decisions being announced five or more years after the principal donor’s death.

- Sixty percent of the 52 foundations succeeded in spending down all their assets, with a median timeline of 10 years. Of course, some of the spend-downs in our sample are in progress, as their deadlines are in the future.

The Edward E. Hazen Foundation exemplifies many of these trends. Founded in 1925, the trustees decided to put their foundation out of business in 2019, when coffers totaled $22 million. Following the murder of George Floyd and the 2020 racial justice protests, the foundation directed its assets quickly to grassroots organizers in communities of color. Five years after the decision, the foundation gave its last slate of grants. It closed its doors in May 2024.

Another example is the Bechtel Foundation. Founded in 1957 by Stephen D. Bechtel Jr., the foundation was originally intended to operate in perpetuity. In 2009, the Bechtels decided to change course in order to create lasting solutions to California’s critical challenges “sooner rather than later.” By 2020, the foundation successfully spent down over $180 million in assets. An even larger example is the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation which, based on the Clarks’ wishes, began a 10-year spend-down journey in 2016. As it nears its sunset, the foundation will have awarded more than $1.3 billion to organizations focusing on educating future generations of engineering leaders, improving the lives of veterans and their families, and providing members of the Washington, DC, community the best opportunity to thrive.

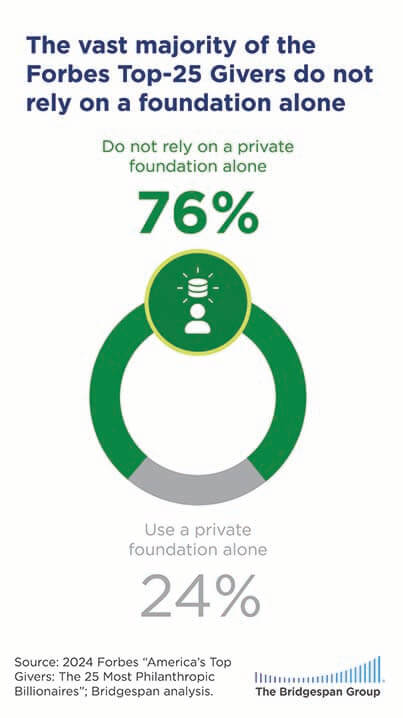

Finding 4. The most generous givers are using multiple giving vehicles rather than relying solely on private foundations to get dollars out the door quickly.

Given the continued ambition among some donors to put their assets to work as quickly as they can to address enormous social challenges, why does the use of spend-down foundations among the wealthiest living donors appear to be declining?

Our analysis found that few of America’s Top-25 Givers use a traditional foundation alone to conduct their giving. One important caveat: while data on foundations are public because they are tax-exempt organizations, data on DAFs, LLCs, and other vehicles are not. Consequently, our data sources are incomplete.

Our analysis found that few of America’s Top-25 Givers use a traditional foundation alone to conduct their giving. One important caveat: while data on foundations are public because they are tax-exempt organizations, data on DAFs, LLCs, and other vehicles are not. Consequently, our data sources are incomplete.

- The vast majority (76 percent) of the Forbes Top-25 Givers do not rely on a foundation alone but use multiple giving vehicles. (Eighty-four percent do use a foundation.) For example, Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna operate not only a traditional foundation, Good Ventures, but also a mix of affiliated 501(c)(3)s (Open Philanthropy), LLCs (Open Philanthropy LLC), 501(c)(4)s (Open Philanthropy Action Fund), and at least one DAF (at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation). They explain the benefit of this diversity of vehicles on their website: “Although we’ve overwhelmingly recommended grants to 501(c)(3) organizations in the past, we are in principle agnostic about a giving opportunity’s tax status. … We occasionally recommended impact investments (e.g., an investment in Impossible Foods to accelerate the development of plant-based meats) or contributions to 501(c)(4)s (e.g., supporting non-political housing advocacy by Greater Washington) in cases where we thought they would be competitive in terms of cost-effectiveness with grants to 501(c)(3)s despite their less generous tax treatment.” To date, Moskovitz and Tuna have distributed more than $2.9 billion through these vehicles.

- At least 40 percent of the Top-25 Givers use DAFs. Since our estimate is based on publicly available information, DAF use is likely significantly greater. While DAFs have been criticized for several reasons, including a lack of transparency at the individual account level, some benefits make them popular among donors.14 Namely, they are tax-advantaged, cost-effective, easy to use, and provide donors anonymity, if desired. As a result, these vehicles may help donors overcome many of the real and persistent psychological barriers that keep donors from scaling their giving, such as fear of public scrutiny.15

- At least 40 percent of the Top-25 Givers have established philanthropic limited liability corporations. All but one of these LLCs were established in the past decade. Some donors like Steve and Connie Ballmer have chosen to exclusively give through an LLC, the Ballmer Group, from the beginning of their philanthropy. John and Laura Arnold opted to convert their foundation from a 501(c)(3) to an LLC. In a recent interview, John Arnold cited the need to “put more research and more evidence-based findings into government” and the “benefits from having one organization where employees could both be experts on the research as well as sit and talk with policymakers to advocate for better policy.”16

There are other popular vehicles. One is what might be called a “special-purpose spend-down”—a limited-life fund designated for a particular purpose, rather than as a general vehicle through which donors give most of their money.17 An example is the Bezos Earth Fund, a $10 billion climate fund started by Jeff Bezos in 2020, which is committed to spending all of its assets by the end of the decade. Another is the Waverley Street Foundation, created by Laurene Powell Jobs, designed to address climate change—in this case focusing on local leaders and organizations. It is committed to spending the entirety of its endowment ($3 billion as of 2022) by 2035.

Another alternative is philanthropic collaboratives, which have seen extraordinary growth over the past decade. A collaborative is not a vehicle per se, but a means to channel funding and accelerate a donor’s pace of giving.

* * *

Our analysis, consistent with Bridgespan’s work over two decades with a range of philanthropists, suggests that there is a growing recognition among donors that giving while living can be a high-impact and worthy pursuit. We are encouraged by the findings presented in this report: in short, it is possible to make headway while living, and there are multiple pathways to do so. To be sure, while it is possible to accelerate giving in a responsible, high-impact way while assets continue to grow, it is not easy.

Whether donors are just starting out or have decades of experience, they may find themselves daunted by the questions they need to answer to accelerate their giving. Yet, delaying a decision can make it even more challenging to reach a donor’s aspiration to give while living as wealth continues to grow.

In our experience, the only way to start is to get started—to set a goal for your giving, make a plan for how to reach those goals, begin piloting approaches to making grants, and learn and refine as you go. In developing a plan, we encourage donors to select giving vehicles that match their goals and strategy, as well as reflect on their own values and preferences for the role that they would like to play in their philanthropy. For those whose wealth lands them on the radar of the Forbes wealthiest Americans list-makers, achieving real progress on giving while living often calls for using more than one vehicle to get funding out the door and drive the desired impact.

Our experience has shown us that for donors to achieve a dramatically different scale of results, they often have to approach their philanthropy dramatically differently. We celebrate donors who have made significant progress toward giving differently and hope this research serves as an inspiration to those who seek to learn from the experiences of others in achieving their own ambitious goals to give.

The authors thank Bridgespan Manager Avi Khullar and Bridgespan Editorial Director Bradley Seeman for their critical help in developing this article.