This research was conducted in collaboration with The Skoll Foundation and is part of The Bridgespan Group’s dedication to equitable systems change through field building and supporting field catalysts. The authors are grateful for the generosity and support of the following organizations for funding this multiyear research effort: California Health Care Foundation, Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, The California Endowment, The Menzies Foundation, and The Skoll Foundation.

The authors also thank the many nonprofit leaders, including Skoll’s global network of field catalysts, for giving their time to be surveyed and for sharing their insights and knowledge in interviews for this report.

In mission-driven circles, systems-change work—which is focused on the root causes of problems—is sometimes treated like an unattainable dream. Excitement grips hold every few years about a promising pathway, only to simmer down once dreamers awaken to the long, hard road to lasting social change. At a recent conference, one funder confided they were tired of peer gatherings focused on “theoretical sea-change shifts” in the sector. “All these big ideas are just talk with no practical next steps or actions,” the funder said.

And yet systems do change. It made us wonder: what does it truly take to nurture equitable systems change? (We are deliberately talking about systems change that centers equity, because not all such work has to. After all, the patient, coordinated, collective work in the United States to unwind reproductive rights or voting protections are changing systems, too.)

At Bridgespan, we call the organizations that are often key to unlocking equitable systems change “field catalysts.” (See “What is a field catalyst?”) One such organization we spoke to thinks of itself as a “midwife of social change,” which has a nice ring to it, too. While equitable systems change requires a diverse set of actors playing distinct and complementary roles across a field or ecosystem,1 field catalysts harmonize and drive that multifaceted work, serving as a kind of nerve center for the matrix of activity needed to transform our inequitably designed systems.2 Think of the critical role Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, played in the eradication of polio, or the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ contribution to the dramatic plunge in teen smoking rates. In another example, the goal of marriage equality in the United States was reached thanks, in part, to the Freedom to Marry organization, which orchestrated its campaign for 12 years.

Behind the scenes, philanthropy often plays a role in these achievements. Take IllumiNative, for instance. For six years, as the head of one of the most well-connected and resourced Native-led organizations in the United States, Crystal Echo Hawk felt she was getting invites to all the right rooms in government, the private sector, and philanthropy circles. However, once she arrived, she says she always felt as if she had been “invited by accident.”

What is a field catalyst?

Population-level impact requires massive change in the entrenched systems that perpetuate inequitable outcomes. As part of these efforts, our research indicates there is an often unseen—at least by funders—yet highly effective type of intermediary or collaborative that we call a “field catalyst.” Each works to mobilize and galvanize myriad actors across a social-change movement, or field, to achieve a shared goal for equitable systems change. Many of society’s major social-change successes have benefited from their critical work, and aspirations for population-level change will remain elusive until we unlock significant capital to support them.

For more on what a field is—and how to help build one—see The Bridgespan Group’s Field Building for Population-Level Change.

Download a PDF of this article to see a list of the field catalysts we studied. Click here to download >>

“There was never any data or discussion about Native kids and people,” says Echo Hawk, whose work at the time focused on improving the health and well-being of Indigenous children. “There was no recognition that if you invest in Native-led solutions, great things happen. I walk the world as a Pawnee woman and felt invisible.” Determined to change that reality, in 2018 Echo Hawk founded IllumiNative, a racial and social-justice field catalyst dedicated to disrupting the invisibility of Native peoples and mobilizing support for Native issues. IllumiNative emerged from the Reclaiming Native Truth (RNT) project, the largest public opinion research and strategy-setting project ever conducted by, for, and about Native peoples. The two-year research effort, designed and led by Echo Hawk, documented how extensive such Native invisibility truly is, finding that 78 percent of Americans know little to nothing about Native people and almost 90 percent of schools in the United States do not teach about Native Americans past the year 1900. RNT identified such invisibility as one of the greatest threats to Native lives and livelihoods, as it is the manifestation of systemic racism.

IllumiNative set out to squash that invisibility, the root cause of so much Native harm, and to “shift culture to change behavior.” Although IllumiNative is still a relatively young field catalyst, it has already seen some successes, including the high-profile name change of a professional American football team to do away with the Native slur it had been called for 87 years.

Here’s how philanthropy fit in. For the RNT research, Echo Hawk secured an initial grant of $2.5 million from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, an unusually generous amount for narrative-change work. Other funders took notice, and the RNT project ultimately raised $3.3 million, which contributed to the depth of data, thought partnership, and follow-up strategy co-developed among Native leaders—and the birth of IllumiNative. Impressed with the success of RNT, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation leaned into its funder network to connect Echo Hawk with the New Venture Fund, which provides fiscal sponsorship to social change leaders. This relationship paved the way for the Pop Culture Collaborative, Novo Foundation, and MacArthur Foundation to each give flexible grants between $500,000 and $750,000 to officially get IllumiNative off the ground.

“Our secret sauce is we had funders who gave us flexible funding and allowed us to just innovate and be. That level of flexibility was amazing and made the work of systems change possible.”

“Ultimately, we wanted an organization that would be a movement of many movements,” says Echo Hawk, embracing the notion that no single organization can solve complex social problems alone. “Our secret sauce is we had funders who gave us flexible funding and allowed us to just innovate and be. That level of flexibility was amazing and made the work of systems change possible.”

Surely there must be other opportunities for funders to support equitable systems change. So we set out to learn more about the origin stories of field catalysts, the challenges they face, and—importantly—the ways in which they believe funders can help them.

Why Should Funders Care About Field Catalysts?

In 2022, The Bridgespan Group surveyed about 100 field catalysts working on a variety of issues, including health equity, gender-based violence, climate change, and education, and interviewed more than 40 leaders.

In 2022, The Bridgespan Group surveyed about 100 field catalysts working on a variety of issues, including health equity, gender-based violence, climate change, and education, and interviewed more than 40 leaders.

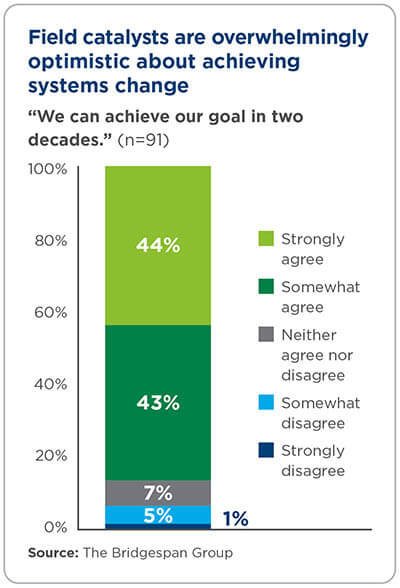

Our survey confirmed that their work could be accelerated with the right support from funders. We found that field catalysts are persistently underfunded, with most needing to raise between half to twice their current budget. Still, because these organizations consistently punch far above their weight, 87 percent of field catalysts believe they would achieve their systems-change goals within just two decades if provided the necessary resources and consistent support. Imagine that! This held true even for leaders of color, who have historically received the lowest amounts of funding.3 Such confidence is grounded in field catalysts' intimate understanding of how to set intermediate goals and adapt strategies to achieve lasting long-term social change.

With an eye for practical next steps, we then documented the origin stories of field catalysts to better understand how philanthropy can, with intention, fertilize the soil these leaders need to launch such efforts as well as how funders can nurture ecosystems so that field catalysts can flourish and thrive. All of our research indicates one key truth: field catalysts are among the highest-leverage investments philanthropy can make when it comes to equitable systems change.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Unlike the strategies of traditional direct-service or advocacy organizations, with which most donors may be familiar, field catalysts are not interested in massively growing their organizations or in scaling programs. Instead, field catalysts focus on massive impact by building, strengthening, and coordinating relationships across actors throughout the ecosystem. They see the world, and their role within it, a little bit differently. While 63 percent call themselves "organizations," 20 percent identify as "collaboratives," and 16 percent as "movements."

“We don’t ask ourselves, ‘What is it that Harambee needs to do?’ We ask, ‘What is it that the system needs, who is best placed to do that, and what is Harambee’s role in that?’”

“We don't ask ourselves, 'What is it that Harambee needs to do?' We ask, 'What is it that the system needs, who is best placed to do that, and what is Harambee's role in that?'” says Kasthuri Soni, CEO of Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, which works to solve youth unemployment in South Africa and Rwanda through partnerships with business, government, civil society, and young people.

Admittedly, such harmonizing work takes a long time—decades, even—but it is necessary to ensure that the entire ecosystem is resilient enough to respond to evolving challenges while still having capacity to be proactive and take advantage of opportunities. This approach also gets results. For instance, the South African National AIDS Council, known as SANAC, has coordinated an effort to reduce by half the country’s rates of HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis by bringing together government, civil society, and the private sector to create collective responses. In another example, Community Solutions has managed to show homelessness in the United States is solvable by helping 14 communities make homelessness rare and brief for an at-risk population, including three communities that have virtually ended both veteran homelessness and chronic homelessness.

In fact, despite the complexity of problems and issues being addressed, about half of the field catalysts who responded to questions on impact reported seeing what they describe as promising progress, with 42 percent saying they see impact growing at a consistent pace, with progress accelerating, and another 10 percent seeing impact accelerate very quickly at scale.

Despite their outsized impact, field catalysts tend to be relatively small, especially in relation to the scale of the problems they tackle. The median budget size of field catalysts we studied is $5 million, and one-third of survey respondents have fewer than 10 people on staff. Notably, the median funding gap of how much field catalysts in our dataset say they need annually to fulfill their mission is just $2.5 million. That means closing that funding gap could be a relative bargain, considering the inroads these efforts can make to building a society characterized by equity and justice.

Despite their outsized impact, field catalysts tend to be relatively small, especially in relation to the scale of the problems they tackle. The median budget size of field catalysts we studied is $5 million, and one-third of survey respondents have fewer than 10 people on staff. Notably, the median funding gap of how much field catalysts in our dataset say they need annually to fulfill their mission is just $2.5 million. That means closing that funding gap could be a relative bargain, considering the inroads these efforts can make to building a society characterized by equity and justice.

The tremendous scope of day-to-day activities of field catalysts can be hard to grasp, especially for those who are accustomed to working with direct-service organizations. In general, most field catalysts use adaptive strategies and often learn their way toward equitable systems change. Only 17 percent of respondents used traditional impact metrics like number of people served. Instead, with the long-term focus required to achieve transformative impact, these organizations rely on a varying set of indicators to gauge if the conditions holding inequities in place have shifted. Our survey revealed indicators that include changes in policy and institutional practices, the strengthening of relationships and networks among stakeholders across the field, or the changing of narratives and shifting of mindsets.

“Systems change doesn't give a damn about year-over-year progress. Systems change is a longer play that needs funders willing to embrace the complexity of the landscapes they are working in.”

"If you have a foundation that cares about year-over-year deliverables on your key performance indicators, that’s a certain type of work, but that’s not systems change. Systems change doesn’t give a damn about year-over-year progress,” says Erin Ricci, senior director of philanthropic partnerships and strategy for Health Care Without Harm, which seeks to transform healthcare worldwide to reduce its environmental footprint. “Systems change is a longer play that needs funders willing to embrace the complexity of the landscapes they are working in."

Where Do Field Catalysts Come From?

Typically, field catalyst leaders are motivated by the realization that a lack of connective tissue coordinating various actors is impeding equitable systems change in their area of work. Before taking on the work of a field catalyst, many of these leaders reported spending 18 months in deep dialogue with other actors in the ecosystem, testing and iterating ideas and priorities while building networks and trust in order to identify the precise needs of the field and ways they could meet them.

- For lessons from social-change makers, please read "Field Catalyst Origin Stories: Lessons from Systems-Change Leaders" >>

- To learn about our multiyear initiative on field building, please see Field Building for Equitable Systems Change >>

Some leaders also pointed to a “moment in time” that sparked a call to action and built early momentum to launch a field catalyst effort. For example, the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) was founded in the aftermath of the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, a time the M4BL network describes as a “critical rebirthing, when a new generation of freedom fighters were coming of age and being politicized by the police killings of young Black people.”

In other cases, funders see opportunities for greater connection across their portfolios. The Families and Workers Fund (FWF) is a coalition of more than 20 donors and a $65 million pooled fund working to build a more equitable US economy. The COVID-19 pandemic brought these donors together because they realized from their individual experience funding economic mobility work that the field was splintered and lacked the partnerships needed to move quickly enough for the moment. Actively reaching out to frontline leaders and communities to understand their needs and vision made it clear to FWF that people would be left out of the official economic response because of systemic racial and gender biases.

“The nonprofit that could reach trans people in rural Alabama wouldn’t be the same one who could reach day laborers sleeping in the Home Depot parking lot. And neither of those organizations would reach government funding,” says Rachel Korberg, FWF’s executive director and co-founder. In addition to deploying $10 million within months of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to frontline organizations, FWF also acted as a much-needed connector in the field by building trusting relationships that would last beyond the immediate crisis.

Regardless of the specific call to action, leaders have choices to make about how to move forward. Those choices are influenced by each field catalyst’s genesis—its origin story. When we studied origin stories, we found there are three major pathways from which these systems-change efforts emerge:

- Evolved: An existing field organization pivots or evolves its work

- Fresh start: A field leader or team launches a new effort

- Funder-founded: A funder drives the creation of a new effort

Evolved field catalysts

In this pathway, the leader of an existing organization, typically a direct-service provider, feels its work is hitting a ceiling. As a result, it intentionally adds the roles of a field catalyst alongside the organization’s existing work. The direct-service activities continue as a laboratory for ideas and a testing ground that can provide valuable proof points to complement field-catalytic work, supporting the broader ecosystem’s efforts to achieve equitable systems change.

The Solutions Journalism Network (SJN) is trying to ignite a global shift in journalism to focus coverage on solving social problems. SJN was originally focused on getting articles in this model in the hands of newsrooms and allowing change to happen one article and one journalist at a time. Although the organization saw success with this direct-service model, SJN soon realized that if journalism were to help achieve an equitable and sustainable world, a systems approach was needed to shift the norms of the industry to center this model of news coverage. Instead of placing one article at a time, SJN started focusing more broadly on influencing the field of journalism by providing training in newsrooms, at convenings, and in journalism schools to shift the thinking and practices of a generation of journalists.

“Once you get to 100 proof points, 101 proof points doesn’t make that much of a difference,” says SJN Co-Founder and CEO David Bornstein. “We could also never meet demand ourselves. It’s like the problem with freeways—you add lanes, but as soon as you add them, they’re full because the cars are coming quicker than you can add lanes. So you must think of a different mode of getting people to where they want to go. That’s when we started seeing the potential of the field-catalyst model. We are now basically an influence organization that runs projects to give credibility to our influence.”

This kind of evolution can be challenging to manage. Pivoting to take on new roles can make it tough to build trust and credibility with other stakeholders. Some evolutionary leaders have found it difficult to attract the funding and talent required to pivot an existing organization.

“It’s like the problem with freeways—you add lanes, but as soon as you add them, they’re full because the cars are coming quicker than you can add lanes. So you must think of a different mode of getting people to where they want to go. That’s when we started seeing the potential of the field-catalyst model.”

In addition, balancing an organization’s focus between addressing root causes and working directly with the community to support immediate needs can put a strain on leaders. “We spend a lot of time as an organization thinking about how we can maintain our resilience as a team and as humans in the face of daunting challenges in the world,” says one US-based social justice field catalyst from our survey. “It’s not a marathon, it’s not a sprint, but it is a relay. We need a sense of urgency, but also need to pace ourselves.”

Fresh-start field catalysts

In this pathway, leaders build on their lived and professional experience in the field to start new organizations focused on doing the work of a field catalyst from the beginning. In some cases, the core ideas of the new organization are incubated at a leader’s previous organization before being spun off into a new organization. More than 60 percent of field catalysts in our dataset were founded as a new organization (including IllumiNative), making this the most common pathway.

These leaders frequently spend extensive time in dialogue with other field actors, identifying the precise needs of the field and ways they can meet them. This time also helps build authentic relationships and the credibility necessary for the success of the new organization.

The leadership of Liberation Ventures, a field catalyst devoted to the US reparations movement, spent almost two years gathering feedback from over 300 people both in and outside of the Black liberation movement before launching. “We were very explicit with people that we were not necessarily going to start an organization and that we were trying to figure out whether our unique combination of skills and experiences could be useful to the broader field, and then, if so, what shape that would take based on the needs,” says Co-Founder and Managing Director Aria Florant, whose previous experience includes grassroots community organizing and management consulting, both in pursuit of racial justice. The learning tour revealed the field was desperately in need of funding as well as additional resources, including the technical assistance and connective-tissue roles that Liberation Ventures now plays for the ecosystem while also being a funding intermediary.

In our previous research,4 we’ve noted examples of this pathway:

- Rebecca Onie and Rocco Perla, both healthcare veterans, launched The Health Initiative as a field catalyst to spur and support a new national conversation on health informed by their deep expertise in healthcare and the drivers of well-being, including community-based work at Health Leads.

- Jordan Kassalow founded VisionSpring to provide affordable eyeglasses globally and, after growing for years, decided to launch EYElliance with Co-Founder and CEO Liz Smith to mobilize a broader ecosystem working to accelerate equitable access to eyeglasses.

- Rosanne Haggerty was a well-respected, longtime leader in the fight against homelessness and the CEO of a New York City nonprofit creating scalable supportive housing when she felt the call to change her approach. She first launched an exploratory project within her direct-service organization to gain an understanding of the surrounding ecosystem and its needs and constraints. She then spun off the work into a new organization, founding Community Solutions, which doesn’t build more homeless shelters but works to end homelessness.

- The Movement for Black Lives—while officially founded in 2014—was born from decades of community-led work, a rich network of relationships, and shared values and experiences across racial justice leaders. Notably, 62 percent of new field-catalyst efforts have funding gaps equal to or larger than half their current budget. Despite this, more than half say they see the field’s impact growing steadily or even accelerating.

Funder-founded field catalysts

Sometimes, funders create field catalysts. This pathway was the least common in our dataset, representing only 11 percent of the field catalysts we studied. However, most of them started in the past 10 years, an early signal of rising interest.

Funder-led field catalysts did not seem to have an advantage when it came to impact. They were just as likely to report their impact is scattered and sporadic as other field catalysts, and expressed similar confidence levels in achieving their goals in two decades.

Most commonly, we found funders created field catalysts in nascent fields where such organizations did not already exist. Funders, because of their vantage point, can sometimes see missing connective tissue and coordination within an ecosystem.

“We realized that in order to achieve the key goals of the movement, funders needed to provide key tools and infrastructure, because ultimately, if there isn’t a strong ‘how’—a strong ecosystem—then we can never get to the ‘what’—the policy, the regulation, or the big win.”

Because funders hold such immense power, however, we approach this third pathway with informed caution. Based on our learning, we urge funders who go this route to lead from behind. Our research supports an approach that nurtures emerging fields by shifting power to other members of the ecosystem and learning alongside them. To be effective, a field catalyst needs to build the trust of ecosystem members, which comes from listening and learning. Taking time to gather with those who are most proximate to the issue will help ensure approaches resonate with the communities they are intended to serve. It takes patience to gain that kind of traction.

Megan Ming Francis of the University of Washington uses the phrase “movement capture” to describe how well-intentioned funders can pressure social movements to change course.5 For example, in the early twentieth century, the NAACP, bending to the will of funders (particularly the Garland Fund), shifted its primary focus from fighting anti-Black violence to that of school integration and economic opportunity—altering the goals of the entire civil rights movement in the United States.6

The prospect of movement capture is a powerful caution to funders interested in supporting systems change. There are risks for well-meaning funders to not only inadvertently hijack the goals of an ecosystem by starting ventures themselves, but also to over-weight their interests in influencing field catalysts born through other pathways. In some cases, existing field catalysts were forced to sunset before achieving their systems-change goals because of a funder’s presence. (See “Watch out: What happens when funders don’t create enabling conditions?”)

Mosaic, which invests in movement infrastructure in the environmental field, was formed through a co-generative process with inclusivity, authenticity, and equity at its core. Over the course of 18 months, Mosaic conducted workshops, surveys, polls, and conversations with more than 100 environmental leaders to develop a strategy and operating principles designed to democratize power and resources through participatory grantmaking.

“During the development process of Mosaic, we realized that in order to achieve the key goals of the movement, funders needed to provide key tools and infrastructure, because ultimately, if there isn’t a strong ‘how’—a strong ecosystem—then we can never get to the ‘what’—the policy, the regulation, or the big win,” says Katie Robinson, Mosaic’s project director, who led its development and launch. Therefore, Mosaic focuses on strengthening infrastructure for the environmental movement by funding work across issues, silos, and communities. Since 2020, Mosaic has invested $11 million in such critical movement infrastructure, benefiting more than 3,000 organizations.

The Challenges Field Catalysts Face

While each pathway has unique nuances, field catalysts reported facing four common challenges.

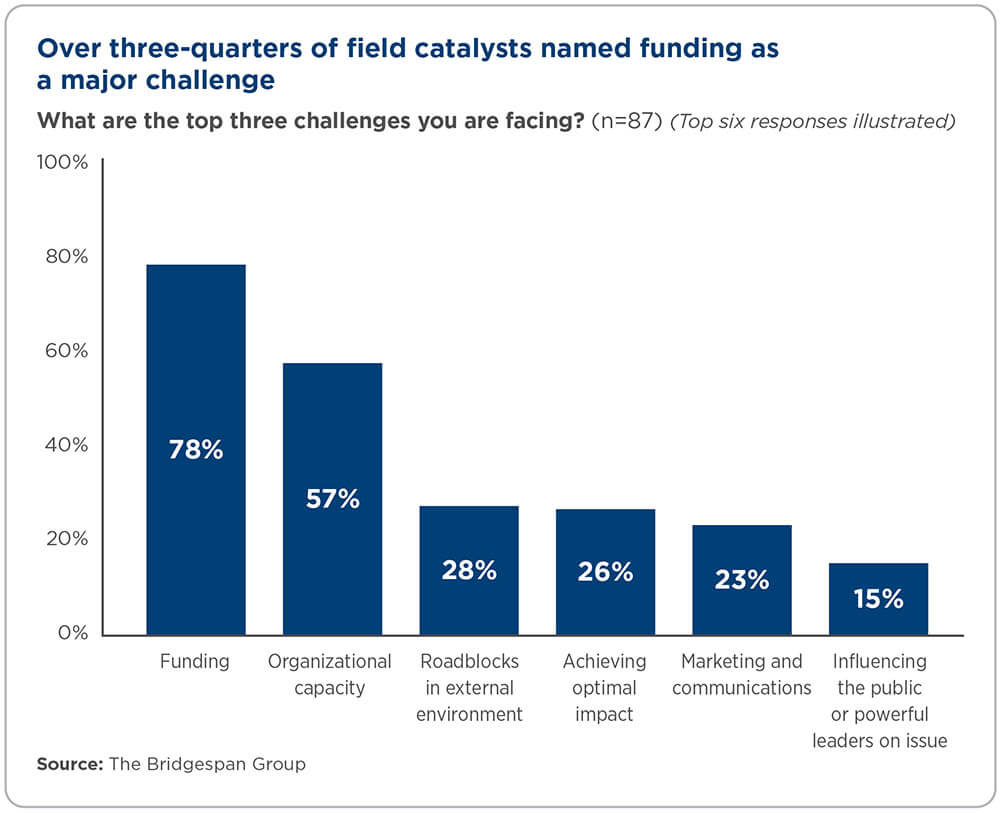

- Challenge 1: Insufficient long-term, flexible funding

About 70 percent of field catalysts reported funding as one of their greatest challenges. Without flexible funds, field catalysts struggle to adapt their strategies, make critical investments, and maintain the momentum of their work over the long term, particularly as they enter a future that’s volatile and polarized. There are hard-won battles to defend or win again when the opposition strikes. What’s more, without the room and resources to innovate creatively and continually learn their way into their roles, the needs of the ecosystem go unfilled and opportunities are lost. And, of course, the challenge of funding can exacerbate and amplify the other challenges. - Challenge 2: Talent constraints

Fifty-seven percent of field catalysts reported they are struggling with significant internal capacity issues. The talent needed for field catalyst work thinks differently than those who scale direct-service models. Instead, talent needs to be comfortable designing ecosystem-level approaches and adapting strategies to changing environments. Leaders shared that their limited capacity to execute their work constrains efforts and weakens partnerships. Difficulty securing and retaining the “right” talent can ultimately weaken a field catalyst’s strategies, overall effectiveness, and resilience. - Challenge 3: Measuring impact on their terms

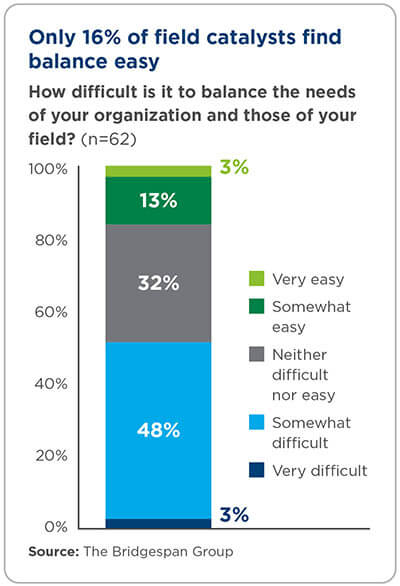

To say that the work of tackling root causes and transforming systems to yield more equitable outcomes is complex is an understatement. In fact, nearly half the respondents in our survey found measurement difficult. Even funders who on some level understand that the social change they seek will take generations to reach might demand stubborn progress markers that ask systems-change leaders to fit into antiquated boxes that ultimately make their work harder to accomplish. This creates a difficult dynamic and can lead field catalysts to make strategic decisions to pursue more clearly defined direct-service work—which our interviews revealed can slow the forward momentum of an ecosystem. Measuring benchmarks that might not matter much for the ultimate goal also distracts field catalysts from helpful thought partnership with their funders. - Challenge 4: Finding balance

About half of field catalysts we surveyed found it somewhat or very difficult to find balance in their work. That can manifest as juggling the needs of the field with those of the organization or as a tension between addressing the immediate needs of the community and the field-catalyst work required to chip away at root causes. Some nonprofit leaders shared they are effectively forced to do catalytic work on top of their day-to-day work because those tasks are not what their organization receives funding for. This not only constrains systems-change potential, but also sets leaders on a path to burnout.

Let’s Get Practical: How Philanthropy Can Advance Social Change by Supporting Field Catalysts

Funders can achieve great progress on social-change goals by seeking field catalysts who are “born from the field”—who our survey suggests are more effective than those hatched in funders’ boardrooms—and cultivating the environments in which they can reach their full potential. The following set of funder recommendations, culled directly from field catalysts themselves on what they say they need to achieve greatest impact, are also born from the field.

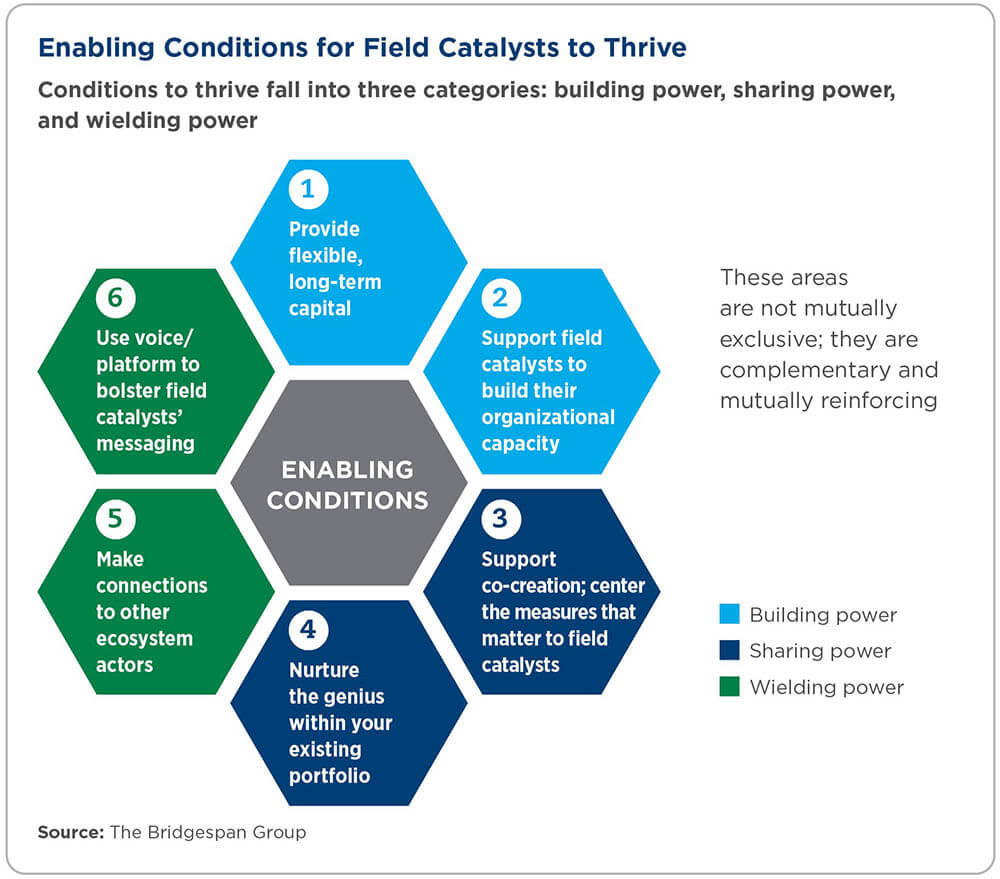

In our survey and interviews, field catalysts explicitly talked about how philanthropy has successfully used its power to help accelerate progress. In the eyes of these systems-change leaders, philanthropy is most supportive when it funds and shares power in ways that foster shared learning and collaboration (instead of competition) among an ecosystem’s actors, including other funders.

This mention of power is important. It is impossible to authentically commit to equitable systems change without considering power; otherwise, the status quo and all its inequity are maintained. In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin touches on power when he lays out a formula for needed social change. He was writing at the height of the civil rights movement—perhaps, the ultimate equitable systems-change moment in the United States—but his words still ring true today. He writes: “I speak of change not on the surface but in the depths—change in the sense of renewal. But renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not—safety, for example, or money, or power.” In other words, reimagining power is a critical pathway to achieving equity and justice.

The Power Moves framework from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy also highlights the need for philanthropy to examine how it can build, share, and wield power for maximum impact. Keeping power dynamics in view and listening to what leaders shared in our survey, this report shares the core guidance we’ve developed for funders to create the enabling conditions for field catalysts to thrive.

We should also note that some of this advice may sound familiar to those who have been exploring the tenets of “trust-based philanthropy.” Supporting field catalysts working toward equitable systems change is a concrete opportunity for funders to apply the principles of trust-based philanthropy as they learn how to build, share, and wield their power. Likewise, we are greatly influenced by the Catalyst 2030 report, Embracing Complexity: Towards a Shared Understanding of Funding Systems Change. Launched at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos in January 2020, Catalyst 2030 is a global movement of social entrepreneurs committed to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.7 Read on to learn what field catalysts say they need.

1. Provide field catalysts with flexible capital

Complex problems take extended time to solve. This kind of time frame requires deep, ongoing dialogue with actors across the ecosystem and continuous adaptation in order to understand changing contexts in the field and respond accordingly.

We have given this advice before: complex, long-term work can only be adequately supported with flexible, multiyear funding and other forms of patient capital, such as endowments. We found large, unrestricted, multiyear grants can be transformative for field catalysts. Field catalysts who had received such funding stood out among those we surveyed because they typically no longer struggled with funding gaps. Removing that burden allows for more attention for the work.

But the reality is that, right now, the level of giving to these kinds of equitable systems-change efforts is falling far short of potential. Our own research on collaborative funds shows that those investing in field building and movements (the types of funds focused on ecosystem giving that would include field catalysts) reported giving between $1–2 billion in 2021.

However, these funds believe they could absorb as much as $10.9 billion annually.8

Specifically, funders can provide flexible capital to support the development of a field catalyst’s key strengths. This might include providing funding that allows for long-term adaptive planning and engagement in the field to understand the problem and vision for equitable systemic change, funding for ecosystem mapping to support the organizing work needed, and providing grantees the space and opportunity to develop the trusting relationships critical to this work. “I wish more funders were funding like they actually wanted to solve the problem,” one field catalyst leader tells us. “It’s not just about check sizes, but also about long-term commitments that enable people to plan for the future.”

BOTTOM LINE: Helps to overcome challenge 1—insufficient funding, which further addresses all the other challenges.

2. Support field catalysts to build their organizational capacity and ongoing sustainability

The work of equitable systems change is dynamic and constantly changing. Field catalysts need strategies that adapt to the churn of evolving field conditions and take advantage of ripe moments or opportunities. Community Solutions’ key management hire early on was someone who could “work without a map” and bring a new imagination not constrained by typical ways of thinking in the homelessness field. Dasra Adolescents Collaborative, which works to ensure India’s 254 million adolescents thrive, learned that prioritizing a team of generalists rather than technical experts allows for organizational flexibility.

Not surprisingly, leaders shared that it can take significant time to find the right talent—those with the “secret sauce” of skills who can thrive in such a dynamic environment. In addition, without the security of sustained funding, it can be difficult to retain such talent. That’s why funder support for talent sourcing and recruitment is so important. Funders can lend their weight toward diversifying sourcing pools to be inclusive of local talent while being mindful of racial biases that often exclude leaders of color. For key positions, they can also cover search firms’ fees.

In addition, funders who provided advice and support to help field catalysts crystallize their strategies were named by 29 percent of field catalysts as helping to accelerate progress. Funders might thought-partner with grantees and provide external support on strategy while being mindful of the risks of movement capture. Without strategic clarity, it is impossible to determine what talent is most needed.

Additionally, equitable systems-change work can be tiring, challenging, stressful, and emotionally draining. Respondents to our survey pointed to such fatigue at this moment in time as a critical challenge. “Many of our staff, as well as many of our partners in the field, are exhausted from the combination of the pandemic and societal and intergenerational trauma, as well as the challenges at the federal level that represent existential threats to democracy and particularly impact vulnerable communities,” says one respondent.

A concrete way to invest in sustainability is to provide funding for sabbaticals, retreats, executive coaching, and other outlets for healing and rejuvenation. This can be particularly needed for social-change leaders of color, who have to navigate the added weight of working to upend systems of oppression and inequities that they themselves are also harmed by.9 A recent study conducted by the Building Movement Project found the toll of this weight to be “immense,” especially for leaders who are women of color.10

BOTTOM LINE: Helps to overcome challenge 2—talent constraints.

3. Center the measures of progress that matter to field catalysts

Leaders in our survey reported that the most helpful funders encourage thoughtful metrics that align with field catalysts’ roles and strengths, and support iterative learning that benefits the entire ecosystem. These funders often adopt a co-creative approach to evaluation that may engage many stakeholders. Likewise, leaders note that it can be harmful and slow progress when funders do not trust field catalysts to develop relevant metrics and instead try to evaluate equitable systems-change work through direct-service standards.

Burdensome reporting requirements of funder-imposed metrics were named by 20 percent of field catalysts as a significant challenge that hinders their work. It is important for funders to keep in mind that, although many field catalysts do engage in some degree of direct-service activities, it is often not the primary focus of their overall work, nor is it at the heart of their efforts to advance equitable systems change.

“We had no initial core funding, which led to a trajectory of growth that relied on aligning with specific funder agendas,” says one field catalyst leader, whose DC-based organization works globally at the intersection of health, education, and nutrition. “This spawned a series of programs over time that, while each [were] successful, were not always strategically connected to one another. The number of sectors we worked in and our approaches to the work proliferated under different funders and different fragmented programmatic leaders. It also created silos and a culture focused on funder needs.”

Field catalysts measured their impact in a variety of ways, including shifts in policy and institutional practices, narrative change and mindset shifts, and the strengthening of relationships and networks among stakeholders across the field, along with community engagement and reduction in the scope of the issue. We encourage funders to learn from field catalysts about what it takes to work toward shared desired outcomes. Funders can also support field catalysts through adjustments in approaches and strategies, without penalty.11

BOTTOM LINE: Helps to overcome challenges 3 and 4—measuring impact and finding balance.

4. Nurture the genius within your existing portfolio and create space for leaders to explore new roles

Most likely, leaders who have the desire to think bigger, at a systemic level, already exist within your grantmaking community. Some of these leaders would benefit from support that allows them to explore their budding interest in taking on ecosystem roles or that ignites the initial spark for a leader to make the mental transition to this work. By nurturing and activating the genius already before you, these leaders can ultimately accelerate the impact of your entire portfolio.

Providing grantees with leadership development support is critical. Investing broadly, deeply, and over time in leadership development helps these leaders reach their full potential and “solve the whole problem.” Patient capital, like an endowment, that allows for leaders to develop is also critical for successful leadership transitions. NOSSAS, an “accelerator for activism” in Brazil that helps communities self-organize, points out that this can be particularly important in developing local leaders in the Global South who might need time to develop relationships with philanthropy. NOSSAS is currently raising capital to create a runway of learning for its next CEO as the baton passes from co-founders with self-proclaimed privileged backgrounds and Western education credentials that US funders often find comfortable to a woman of color whose entire professional and life experience has been in Brazil.

Connecting leaders with a diverse set of experiences can help create intentional on ramps for them to explore field catalyst roles if they choose to, as there are sometimes new skills and mindsets needed to do this work well. For instance, field catalysts say it is helpful when funders use their convening power to regularly bring grantees together for collaborative planning and discussion of issues and shared barriers within their ecosystems. Designing these gatherings with equity in mind (including ensuring a diverse group of participants—across race, gender, role, and so on—and making room for a variety of voices and work styles) will create space for grantees to raise their hands to take on new roles. Likewise, the networks these leaders have already built should be seen as assets and fostered.

BOTTOM LINE: Helps to overcome challenges 2, 3, and 4—talent constraints, measuring impact, and finding balance.

5. Make connections for field catalysts to funders and other ecosystem actors

Granted, fundraising for all nonprofits is hard. But we found fundraising for systems-change work can be even tougher. Connecting leaders within your portfolio to other funders is important given the added difficulty. A key moment in IllumiNative’s origin story, for example, was its connection to the New Venture Fund made possible by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Because of the connective-tissue role field catalysts play, helping to expand the funding network of field catalysts not only helps the success of these organizations, but it also supports the collective success of the entire ecosystem. In our survey, 15 percent of field catalysts named connecting their leaders to other funders as a type of support from funders that was most helpful.

Fundraising difficulties felt by field catalysts are more pronounced for organizations headed by leaders of color because of race-based barriers to capital. Racial bias—both personal and institutional, conscious and unconscious—creeps into all parts of the philanthropic and grantmaking process. The result is that nonprofit organizations led by people of color receive less money than their white peers.12

Given the funding difficulties, funders already supporting field catalysts can wield power among philanthropic peers by serving as evangelists of equitable systems-change work and help build an understanding about the critical roles field catalysts play.

BOTTOM LINE: Helps to overcome challenge 1—insufficient funding, which then helps to overcome all the other barriers.

6. Use your voice and platform to bolster the messaging of field catalysts

Funders can leverage their reputations to champion catalytic leaders and shine a spotlight on the issues they are working on. In other words, they can wield their power in service of the field. This use of a funder’s social and political capital can be especially beneficial for leaders of color and local leaders in the Global South. One specific way funders can wield their power is by using their platforms to provide speaking engagements and thought-leadership opportunities to grantees. Funders can also have their institutions incorporate field catalysts’ messaging to amplify the reach and effectiveness of these leaders with key stakeholders. A funder’s help in raising the visibility of these issues can be particularly influential with policymakers and government officials, who may be critical to the ultimate success of equitable systems change.

BOTTOM LINE: In the short term, this helps overcome challenge 4—finding balance. Long term, this is also a practical way for funders to embrace a “systems mindset,” as Catalyst 2030 puts it.

Watch out: What happens when funders don’t create enabling conditions?

Orchestrating the work of equitable systems change is incredibly challenging. We investigated three examples where the journey was fraught and in which organizations were forced to ultimately sunset without having achieved their systems-change goals, leaving leaders burned out and frustrated. We see this not as a leader’s or an organization’s failure, but as a systemic failure of the social sector for not adequately supporting the types of organizations or leaders who are doing the most complex and messy systems-change work.

Sometimes a leader’s expertise and proximate experience is not valued. In one case, a US-based BIPOC-led effort was incubated under a funder’s aegis and then deliberately spun out by its CEO to focus on field-catalyzing work. Unfortunately, the board and key funders did not trust this vision. Instead of providing the CEO with the freedom and flexibility to learn into the role, including by using relevant, tailored metrics, the organization was forced by these key stakeholders to grow its direct-service work, ultimately leading to financial and organizational challenges it could not overcome. “When I think back,” says the former CEO, “all I can say is, there was just such missed opportunity in the field. We were so close.”

At other times, a leader’s desire to think bigger is not authentically embraced. One longtime CEO of a locally led NGO in the Global South saw a need to move toward more ecosystem-level work. “Organizations may either go deep or go wide,” notes the leader. Tensions rose when the organization could not do both. The CEO wanted to move away from something branded and work more behind the scenes managing a collaborative approach. “You can’t just have one actor or five actors—you need a flotilla of boats working to fix the whole population-level problem for the change to be enduring,” he said. Lacking the proper support—time, flexibility, and staff—to successfully make the pivot left the CEO so frustrated he decided to leave the organization he had led for 20 years.

And sometimes funding challenges stop a field catalyst from fully developing its strengths and becoming what the field truly needs. For one organization, a generous one-time gift from MacKenzie Scott allowed it to take stock of what the field needed. After conversations with nearly 40 leaders across the ecosystem as well as the organization’s staff and board, the leader concluded that the needs of the evolving field were too great for what the organization could offer given its struggles with attracting long-term funding. There weren’t enough Scotts to sustain the organization over the long term. So it decided to sunset and instead use its resources to document and share key lessons from its experiences and help seed the field with the research-focused capacity it desperately needed.

The consistent misstep through these examples: funders not trusting systems leaders enough to do the work those leaders see is needed for lasting social change.

Final Thoughts

Our research started in search of practical advice for funders interested in the kind of social change required to build a more equitable society. Given that investing in field catalysts is the clearest way to get there, it made sense to better understand the origin stories of these critical efforts. Our research revealed that funder behavior does matter. By intentionally creating the conditions that enable a field catalyst to thrive, funders can shift the odds in favor of lasting population-level change. Alternatively, we found funders can also create obstacles and roadblocks for systems-change leaders that will continue to slow their progress. Indeed, to borrow from one of the great comic book origin stories, a young Peter Parker was wisely warned: “With great power comes great responsibility.” (You didn’t think we would let a report on “origin stories” to finish without making a Spider-Man reference, did you?) Comics aside, the advice speaks to why the issue of power runs deep in our guidance to funders.

We also started this discussion with hope. As a reminder, nearly 90 percent of field catalysts believe they would achieve their systems-change goals within just two decades if provided the necessary resources and consistent support. Of all the data points our survey uncovered, that is perhaps the most striking, and one that should never be forgotten. It is a sign that, as complex as the problems are, as difficult as the work is to overcome them, as far away as the finish line may seem, there is a pathway to get there. And the reality is, it won’t be a single superhero who will swoop in to save the day. Instead, it will be an entire collective—nonprofit field actors, grassroots efforts, field catalysts, impacted people, and, yes, funders—strategically and intentionally working together, that will get us there.

Lija Farnham and Emma Nothmann are partners at The Bridgespan Group, based in San Francisco. Kevin Crouch is a manager, also in Bridgespan’s San Francisco office. Cora Daniels is editorial director in Bridgespan’s New York office. The authors thank Bridgespan colleagues Carolyn Daly and Nicole Austin-Thomas for their insights and contributions to the research. The authors also thank the Skoll Foundation for its collaboration for this report, including the thought partnership of Chief Executive Officer Don Gips, Chief Strategy Officer Shivani Garg Patel, Director of Strategy and Learning Nadir Shams, and Community Director Vanessa Wai.