From time to time, mission-driven leaders find themselves working behind the scenes on the big picture. Maybe they convene leaders from across social, public, and private sectors or research root causes that allow underlying challenges to persist. Perhaps they work to change narratives through mass media or examine in some other way how the various players of an ecosystem can coordinate. In all such cases, the leaders’ frames of reference are less about helping individuals in need in the moment—and more about changing inequitable systems forever.

If this sounds familiar, then this article is for you.

We call the doers of this multifaceted work “field catalysts,”1 and we have been studying and learning from these systems-change leaders for more than five years now (see “What is a field catalyst?”). In our latest research, we surveyed about 100 of these social-change makers in a variety of fields, including health equity, gender-based violence, climate change, and education, and interviewed more than 40 leaders, all to better understand what it takes for field catalysts to launch and thrive. Our accompanying article, “Equitable Systems Change: Funding Field Catalysts from Origins to Revolutionizing the World,” goes deep into data and trends from the survey and interviews to offer guidance for funders. Here, we share lessons from field catalysts for fellow leaders.

What is a field catalyst?

Population-level impact requires massive change in the entrenched systems that perpetuate inequitable outcomes. As part of these efforts, our research indicates there is an often unseen—at least by funders—yet highly effective type of intermediary or collaborative that we call a “field catalyst.” Each works to mobilize and galvanize myriad actors across a social-change movement, or field, to achieve a shared goal for equitable systems change. Many of society’s major social-change successes have benefited from their critical work, and aspirations for population-level change will remain elusive until we unlock significant capital to support them.

For more on what a field is—and how to help build one—see The Bridgespan Group’s Field Building for Population-Level Change.

So You Want to Be a Field Catalyst?

Field catalysts play a distinct, critical, and an often unseen (especially by funders) set of roles in the broader ecosystem in service of equitable systems change. (We deliberately researched systems change that centers equity, because not all such work has to. For instance, the patient, coordinated, collective work in the United States to unwind reproductive rights or voting protections are changing systems, too.) Those roles include diagnosing and assessing the core problem and full landscape of actors devoted to it, advocating or shining a spotlight on an issue, and connecting and organizing actors around a shared goal, as well as filling any critical gaps in collective effort toward that goal.2

“Our mantra is to stay in love with the problem, not our solution—we shift and shape to what is needed,” says Kasthuri Soni, CEO of Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, a field catalyst that works to solve youth unemployment in South Africa and Rwanda.

Field catalysts tend to emerge from the field in two ways: either as new efforts or in the evolution of an existing organization. In our survey, 27 percent of field catalysts emerged from existing organizations, and 62 percent represented new efforts. (Funders sometimes create field catalysts, too, but we approach this route with informed caution because of the immense power funders hold, which can warp the field.)

“Our mantra is to stay in love with the problem, not our solution—we shift and shape to what is needed.”

Field catalysts emerge from existing organizations, typically direct-service providers, when a leader feels the work is hitting a ceiling and so intentionally pushes the organization to take on catalytic roles. By contrast, new field catalysts are born when leaders use their experiences in the field—whether lived, professional, or both—to start something fresh with the specific purpose of changing systems. Sometimes, the core ideas of the new organization are incubated at the leader’s previous organization and then spun off into a new organization.

In both cases, leaders are called to the work by the realization that a significant obstacle to equitable systems change for their fields is a lack of connective tissue needed to coordinate various actors across the ecosystem. “We wanted an organization that wasn’t going to solve it all itself, but instead was really a movement of movements,” says Crystal Echo Hawk, executive director of IllumiNative, which works to disrupt the invisibility of Native peoples and issues.

Some leaders have also pointed to a “moment in time” that sparked a call to action and was able to build early momentum to launch a field catalyst. For example, the Movement for Black Lives was founded in the aftermath of the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

Learn Your Way into the Work and Center Equity

Successful field catalysts note the importance of being in deep dialogue with others in the field prior to and during their launch. Our survey found many leaders of field catalysts spent approximately 18 months in such dialogue, testing and iterating ideas and priorities to identify the precise needs of the field and ways they could meet them. Liberation Ventures, a field catalyst that works in the US movement for reparations, talked to 300 people across the field over six months to craft a concept note that is constantly evolving.

A critical step to build trust is to center the voices and perspectives of those most affected by inequitable systems themselves.

This level of deep dialogue, or “learning your way,” is not only needed to determine what work should be pursued and how to do it, but is also critical to building the networks, trust, and credibility necessary for that work to happen. These systems-change leaders note that sometimes it can be difficult for other field actors and funders to embrace how an organization has evolved to take on new roles to live into being a field catalyst. Similarly, field catalysts started as new efforts sometimes find field actors and funders might need some convincing of the importance of a field’s need for connective tissue. Unfortunately, there is no shortcut—building credibility and trust takes time.

A critical step to build that trust is to center the voices and perspectives of those most affected by inequitable systems themselves. Dasra Adolescents Collaborative, for example, focuses on the experiences of adolescent girls as it works to improve social and economic outcomes for the entire vulnerable community of young people in India, where there are now more adolescents than in any other country worldwide.

Likewise, field catalysts strive to center the most affected in their leadership and governance. VillageReach, a global health organization originally founded in Seattle that works to transform health care delivery in Africa, has deliberately moved staff positions out of the United States to Africa. Now, 70 percent of its staff—including leadership—are based in sub-Saharan Africa to live into its goal of being “locally driven and globally connected.” VillageReach’s CEO Emily Bancroft candidly shares: “I have told my board that I hope our next CEO will be of African descent.” Likewise, NOSSAS, a power-building organization focused on democracy and civic engagement in Brazil, is undertaking an executive leadership transition that includes fundraising for an endowment to create a runway for its new CEO, a Brazilian woman of color, who will take the reins after its upperclass, Western-educated Brazilian co-founder steps down.

Overcoming Field Catalyst Challenges

Field catalysts consistently reported facing four common challenges—and offered ways in which they’ve been able to sidestep them.

Talent constraints

Fifty-seven percent of field catalysts report they are struggling with significant internal capacity issues. Field catalysts are not interested in growing their organizations or scaling programs; rather, they focus on impact at scale by building, strengthening, and coordinating relationships across an ecosystem. Thus, the talent that field catalysts seek thinks differently than staff at direct-service organizations, with emphases on the ability to envision ecosystem approaches and a comfort with work that continuously evolves. To deal with these talent constraints, leaders we spoke with shared several key lessons:

- Think differently in hiring. If you are hoping to hire talent that thinks differently, then you have to think differently when hiring talent. That might mean placing more value on imagination and innovative thinking. Liberation Ventures likens it to looking for talent with a start-up mindset. Or it could mean prioritizing a team of generalists rather than technical experts: Dasra Adolescents Collaborative, for example, went against funder advice to do just that. Also consider looking beyond the field or beyond the sector for talent that might have fresh perspectives on the issue. Community Solutions, which works to end homelessness in the United States, decided it needed someone who could “work without a map” and found that in a person with a military background who was used to working in uncertain contexts.

- Deploy talent differently. There is a bit of a paradox involved with putting teams to work. If an organization does not have the level of talent needed, it will be impossible to deploy staff to successfully fulfill the organization’s vision. However, if the organization is struggling to get clarity on strategy (see “Finding balance”), it will not be able to staff up appropriately. When thinking about deploying talent, don’t be constrained by traditional silos and job descriptions. Just as the organization’s work of equitable systems change is multifaceted, the same should be true for how you think about staffing. The Solutions Journalism Network (SJN) reorganized around approaches and supports for individuals, institutions, and collaboratives, rather than traditional issue‑based silos and departments.

- Surround yourself with different types of thinkers. Field catalysts not only think differently in hiring the “right” talent, but they also think differently when it comes to the allies and thought partners they surround themselves with. If your board has not bought on to an ecosystem-level approach, you will never get the space necessary to learn your way into equitable systems change. It can become difficult to keep your organization on course when faced with such tension. “From the very first board meeting, the board made demands that were more suitable for the strategy of a direct‑service organization,” said the BIPOC leader of one US-based field catalyst that was forced to sunset because of the misalignment. “I should have said we already have a plan for what type of organization we wanted to be, but I succumbed to the requests, and things began to shift. When I think back, all I can say is, there was just such missed opportunity in the field. We were so close.”

Measuring impact

Nearly half of respondents in our survey found it difficult to measure their impact for funders. The reality is that systems change is a multi-decade effort. Field catalysts often rely on a variety of measurement indicators that reflect the scope of progress of the ecosystem overall. Because of the complexity of the work, it is critical to demonstrate progress on both longer-term and nearer-term indicators and communicate that progress to a variety of stakeholders to build momentum. The time frame and the adaptive nature of the work point to the need for a new paradigm for measurement, supporting ongoing impact measurement and learning through a “balanced breakfast” of metrics, milestones, and indicators. A balanced approach includes four subcategories:

- Use principles that center equity and learning. Be clear on what you seek to measure and why. Measures should explicitly seek to understand equity, race, and power as critical markers of how the field functions and produces outcomes. Center outcomes that matter to those most affected by inequitable systems. Adopt a learning mindset to determine what is working and what is not, and an iterative approach to make shifts and course corrections along the way.

- Track the state of the field’s development. A field’s development toward achieving equitable systems change can be tracked through some combination of five characteristics:

- Knowledge base—the body of research that helps the field understand the issues and identify and analyze barriers

- Diverse actors—individuals and organizations that together help the field develop a shared identity and common vision

- Field-level agenda—the combination of approaches actors will pursue

- Infrastructure—the connective tissue that enables greater innovation, collaboration, and improvement across the field

- Resources—both financial and non-financial capital to support the field

Understanding the state of these characteristics provides a wide-angle view of the interrelated approaches that are needed to advance the field as a whole. To help determine the state of your field’s development, we have created the Field Diagnostic Tool: Assessing a Field’s Progression. It dives deep into how the characteristics above manifest in one field example and offers questions for reflection.

- Monitor progress toward equitable systems change. Durable, equitable population-level change requires shifting conditions that are holding the problem in place. That might include some combination of the following:

- A shift in government policies or institutional rules and priorities, or a shift in the practices or activities of entities targeted to improve social and environmental progress

- An increase in the flow of resources—money, people, knowledge, infrastructure—that are allocated to the issue

- An improvement in quality of relationships—for instance, has communication improved among actors in the field, especially among those with differing histories or viewpoints?

- A shift in power dynamics, the distribution of decision-making power, and both formal and informal influence

- A change in mental models—signs that deeply held beliefs and assumptions are beginning to crumble3

The key is to monitor progress in ways that matter to your organization. One field catalyst explained their holistic approach to measurement this way: “Recent conversations and convenings where more and more groups and organizations are working to strategize and think together are important field milestones or indicators. We are also starting to see more nodes for coordination and collaboration emerge, as well as some real collective strategic thinking.”

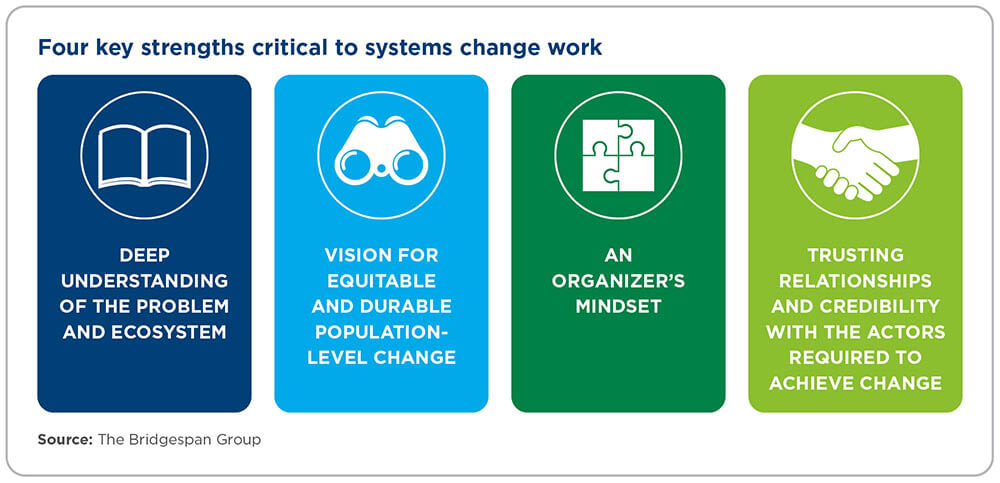

- Don’t forget the health and development of your own organization. Measure your organization’s development by explicitly tracking your success in exhibiting the strengths of field catalysts. These include having a deep understanding of the problem and ecosystem, a vision for equitable change, and an organizer’s mindset, as well as whether you hold trusting relationships and credibility with the actors required to achieve change.4 Meanwhile, indicators of a field catalyst’s overall health include funding and relationships with funders, leadership and staff wellness, strategic clarity, and board development.

Finding balance

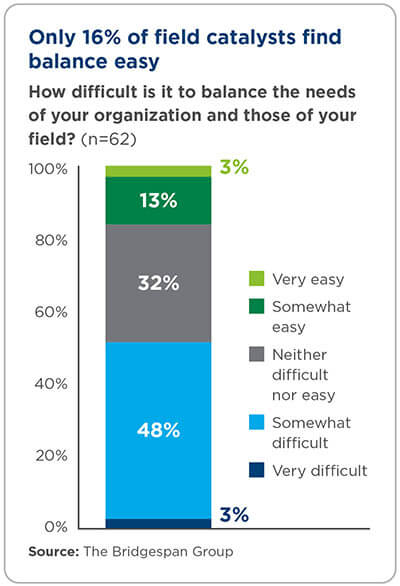

Of field catalysts who answered questions about balance, about half find it somewhat or very difficult to find balance in their work. They may find it challenging to balance long-term field-level work with urgent opportunities and challenges as they arise. Or they may experience tension between a desire for staff retention and sustainability and the reality that field catalysts are often responding to external roadblocks and threats to progress. Several field catalysts, for example, spoke of political polarization or political violence as key external roadblocks. Or they may struggle to find the right balance between direct-service work and systems-change work. The end results are that field catalysts are often left with impossible choices as they deal with the urgency of the existential threats they are battling while raising enough funding for the next year of work so they can guarantee salaries.

Of field catalysts who answered questions about balance, about half find it somewhat or very difficult to find balance in their work. They may find it challenging to balance long-term field-level work with urgent opportunities and challenges as they arise. Or they may experience tension between a desire for staff retention and sustainability and the reality that field catalysts are often responding to external roadblocks and threats to progress. Several field catalysts, for example, spoke of political polarization or political violence as key external roadblocks. Or they may struggle to find the right balance between direct-service work and systems-change work. The end results are that field catalysts are often left with impossible choices as they deal with the urgency of the existential threats they are battling while raising enough funding for the next year of work so they can guarantee salaries.

Admittedly, funders can play a critical role in the ways an organization’s work is prioritized. Over the years, we have heard from many nonprofit leaders who are, in essence, doing their catalytic work on top of their day-to-day work because it is not the primary work for which their organization receives funding. Given that reality, here is advice from the field catalysts we spoke with on how to find balance:

“The key is for us to move away from linear growth that comes with each new direct-service partnership being a success in and of itself … [to] always [be] thinking about the portfolio of partnerships needed to transform many people and organizations with whom we cannot have a direct-service interaction.”

- Be purposeful with your direct-service work. For field catalysts who are balancing direct-service and systems-change work, quality matters more than quantity. The goal is to limit the space direct-service work takes up to leave room for systems change. Some field catalysts found it easier to balance when approaching direct service as a laboratory for ideas. Indeed, your direct-service work can be a way to establish proof points to better make the case for your catalytic work toward equitable systems change. “The key is for us to move away from linear growth that comes with each new direct-service partnership being a success in and of itself,” says David Bornstein, CEO of SJN, which is trying to ignite a global shift in journalism toward focusing on solutions to social problems, rather than the problems themselves. Instead, he says, his organization’s goal is to “always [be] thinking about the portfolio of partnerships needed to transform many people and organizations with whom we cannot have a direct-service interaction.”

- Stay focused on the collective. The work of a field catalyst requires co-creation, authentic listening, and constant adaptation to meet the needs of the field’s evolving goals. Field catalysts hold trusting relationships with other actors and thus can continuously engage the broader field in prioritizing and reprioritizing. Some field catalysts warned against being too concerned about getting credit for progress. “There is a large distinction between needs of individual organizations and needs of the field or movement,” says Rosanne Haggerty, CEO of Community Solutions, which is devoted to ending homelessness in the United States. “My advice would be to commit to the shared aim and work on adapting your organization—even if that means merging or sunsetting your organization—in service of the larger goal.”

- Don’t forget the needs of your staff. The problems are big and the needs are large, but if your organization is suffering capacity issues, the risk is that staff will become burned out and ineffective. While the collective needs will always be your North Star, your organization can not serve the field effectively if it is not functioning well itself. “It’s like putting on your oxygen mask first so you’re able to help others,” says Karen Cowe, CEO of Ten Strands, which works to build environmental literacy in California’s elementary to high school students.

Lack of sufficient, long-term, flexible funding

About 70 percent of field catalysts we surveyed named funding as one of their greatest challenges. Our survey found that the median funding gap of how much field catalysts say they need annually to fulfill their mission is just $2.5 million. “Being behind the scenes is lethal from a fundraising perspective,” says the CEO of a US-based field catalyst trying to improve health. “How do you tell your story when the story is by design invisible? We get asked all the time what kind of organization we are. It drives us crazy. The truth is, we are whatever we need to be to achieve the aim. Unfortunately, there is no box to check for that, which often means we don’t get funded.”

About 70 percent of field catalysts we surveyed named funding as one of their greatest challenges. Our survey found that the median funding gap of how much field catalysts say they need annually to fulfill their mission is just $2.5 million. “Being behind the scenes is lethal from a fundraising perspective,” says the CEO of a US-based field catalyst trying to improve health. “How do you tell your story when the story is by design invisible? We get asked all the time what kind of organization we are. It drives us crazy. The truth is, we are whatever we need to be to achieve the aim. Unfortunately, there is no box to check for that, which often means we don’t get funded.”

In fact, the lack of unrestricted, multiyear funding can exacerbate the other three challenges we discussed above, making it tougher to take advantage of any of the advice shared. We wish we had heard more examples of promising approaches. However, given the crux of this challenge, as well as its enormity, we believe the burden to overcome this challenge really falls on funders, not nonprofit leaders. To support that end, we wrote an entire article for funders with guidance culled from our survey and research.

That being said, when entering conversations with funders, leaders might find it helpful to lean into and celebrate the strengths of field catalysts. Our previous research has identified the following four key strengths, which are critical to unlocking equitable systems change. Be sure to elevate how these strengths show up in the work of your organization.

Moving Forward

Thank you. Thank you for the important work you do as a field catalyst, or will do if you become one. Thank you for your commitment to equitable systems change. Simply, thank you for thinking bigger and reaching farther for the benefit of all. We know the essential work of field catalysts is complex, difficult, and long. Importantly, we see the struggles and challenges field catalysts experience, not as a failure of individual leaders or organizations, but rather as a failure of the system to support critical work.

Lastly, remember that you are not alone in this work—even if the reality of being undervalued and underfunded can make it feel that way. Instead, consider that the insights shared in this short article are a small taste of the tremendous community of fellow catalysts and allies who have your back. After all—as field catalysts know too well—the collective, the community, the ecosystem, will always get you farther than going it alone.

The authors thank Bridgespan colleagues Carolyn Daly and Nicole Austin-Thomas for their contributions to the research. The authors also thank the Skoll Foundation for its thought partnership and thank Skoll’s global network of field catalysts for their insights.