Executive Summary

There is a troubling injustice in America’s Black rural South: the same communities that played a disproportionate role in building the nation’s wealth face the highest levels of poverty today. Approximately 30 percent of Black residents in non-metropolitan Southern areas live in poverty—a higher rate than for any other race or ethnic group, urban or non-urban.1

Such poverty is exceedingly difficult for young people to escape. Of the approximately 200 rural counties in the South with Black populations of 25 percent or more (what we here refer to as the “Black rural South” 2), all but two land in the bottom half nationwide for upward mobility for young people.3 And despite the determination of young people in the region and the rich human, social, and cultural capital of their communities, the Black rural South lags behind national averages on many benchmarks, including this one: while over a quarter of the US population lives in the South, only 3 percent of philanthropic dollars nationwide flow to the region,4and only a fraction of that to rural communities of color.

In 2018, The Bridgespan Group partnered with National 4-H Council on a field report, Social Mobility in Rural America. In that report, we identified six factors that may foster economic mobility—the chance to climb the income ladder—present in a subset of rural communities that have been most successful at enabling young people to build pathways out of poverty. We were struck by the common themes across these communities, yet we also know that rural America is not a monolith and that our research touched less than 1 percent of rural counties in the United States. In addition, most of the rural counties featured in our original report that are managing to help their young people transcend poverty do not have meaningfully large Black populations with enduring legacies of slavery.

Given this context, Bridgespan and National 4-H Council have partnered again to focus squarely on economic mobility in the Black rural South. In our conversations with more than 80 nonprofit leaders; Cooperative Extension staff at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs; including those administering 4-H);5 and funders, researchers, and field experts in the region, we found much to be excited about: caring communities and innovative organizations are trying to move the needle on economic mobility for young people. However, we also found that a profound and ubiquitous lack of philanthropic funding hampers these efforts. The Black rural South is at the intersection of three philanthropic funding challenges: rural communities see less funding than their metro counterparts;6 the South as a whole has historically been underfunded; and leaders of color receive less funding than white leaders.7

Funders with fresh mindsets have a huge and timely opportunity

Throughout our conversations, we heard a palpable sense of urgency for what philanthropy can accomplish if it acts now. Newly available large-scale federal funding has the potential to benefit communities in the Black rural South—if they can find ways to access those dollars. What’s more, a current push for broadband expansion has the potential to connect young people to education and work opportunities if it makes its way to rural Black communities. We also see exciting energy and experimentation across the region from funders and nonprofits alike, including many burgeoning efforts to lift up young people. Indeed, the public dollars and technology are, in theory, available, and innovation is already in play. But funders can play a pivotal role in helping the Black rural South access the available resources and maximize the momentum of this moment.

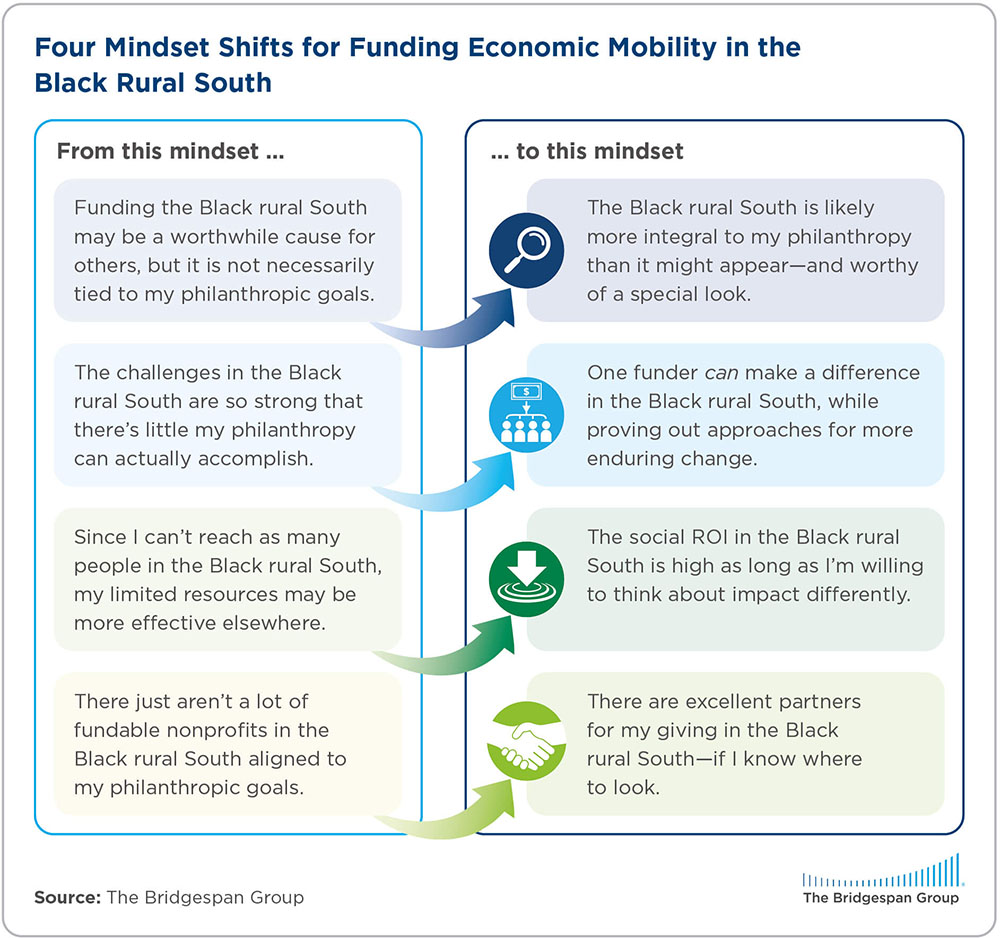

Tapping into opportunities in the Black rural South requires new thinking, ranging from dispelling framings and misconceptions that deter funding to encouraging mindsets that can help fuel economic mobility for young people.

1. The Black rural South is likely more integral to your philanthropy than it might appear—and worthy of a special look. Whether focused on education, mental health, women’s empowerment, or other issue areas, funders looking to move the needle on equity and economic mobility in the United States cannot be successful without addressing this high-need region—a region closely tied to the country as a whole through migration and wide-reaching public policy. In fact, your funding is likely already affecting the Black rural South: if you’re not focused on it, there’s a chance you’re contributing to an ever-widening divide.

2. One committed funder can make a difference, while field-testing approaches for more enduring change. Funders intimidated by the scope of the need might instead consider the scope of opportunity. There are many entry points for funding: from strengthening schools to positive youth-development programs, cradle-to-career support to financial service access, broadband to power building, and even direct cash transfers, funders are supporting a range of efforts, every one of which needs more funding to test out which strategies will work best in places of persistent poverty.

3. In the Black rural South, social ROI—the impact a funder achieves with each dollar invested—is high as long as you’re willing to think about impact differently. Advancing economic mobility in the Black rural South requires depth, not breadth. Funders willing to invest in smaller populations and exercise staying power can reach entire communities and truly change systems. Funders can also help communities connect with public dollars to multiply their impact. Case in point: The Center on Rural Innovation (CORI) estimates that $9.5 million in philanthropy to CORI has yielded $169 million in grants (including federal) and follow-on capital going directly to the rural communities in which CORI engaged.

4. You have excellent partners for giving in the Black rural South—if you know where to look. Funding in the Black rural South is highly relational: intermediaries and local leaders can help direct funding with ease. Every foundation, feminist fund, credit union, HBCU, and national network we spoke with centers on being in relationship with communities, earning their trust, and empowering them to achieve their goals. And there are many local Black leaders ready for funding.

The Black rural South is ready

Creating pathways out of poverty for young people in the Black rural South is difficult. But for funders willing to adopt these mindsets, this is an area where even one funder—in fact, especially one funder—can help realize change. And the Black rural South is ready. We see a region hungry for change, and we see funders leaning into the need and promise of the Black rural South.