The troubled economy has put merging with or acquiring another organization front and center on the radar for the senior managers of many struggling nonprofits. Indeed, a Bridgespan Group poll of nonprofit executive directors found that 20 percent of 117 respondents stated that mergers could play a role in how they respond to the economic downturn. These leaders may consider mergers and acquisitions (M&A) reactively, as a way to shore up finances, to make their organizations appear more attractive to funders or to address a succession vacuum. But the time is also ripe for the leaders of healthy organizations to consider M&A proactively—as a way to strengthen effectiveness, spread best practices, expand reach and—yes—to do all of this more cost-effectively, making best use of scarce resources. Unfortunately, few organizations or funders think of M&A in this way.

Nonetheless, it’s true. There is far more potential for M&A to create value in the nonprofit sector than most people realize. The sector is highly fragmented (there are more nonprofit organizations than lawyers in the United States), and the economy has made M&A a mainstream topic of conversation. Now is the time for the strongest, most effective organizations to use it as a strategic tool to further their impact.

To do so, they must overcome some barriers. For one, there are no financial incentives driving deals, as there are in the for-profit arena—and that situation is unlikely to change. Moreover, there are few financial “matchmakers” (as there are in the corporate world) to help leaders identify, explore and then finance potential merger options, and scarce guidance on how to evaluate potential deals and structure them so that they’ll work. These latter barriers could fall, however, if even a modest number of funders have the will to dismantle them.

What’s needed is a better understanding of how M&A can and has worked as a strategic tool for nonprofits. The sector can boast a number of highly experienced individuals who have helped nonprofits achieve successful mergers. David LaPiana and his organization, LaPiana Associates, Inc., for example, have been involved in this area for years. But to date, general research on nonprofit M&A tends to be based on experience with individual transactions and qualitative rather than quantitative. To address the gap, the Bridgespan Group undertook a research project that focused on the frequency and attributes of M&A activity among nonprofits in four states over an 11-year period. (Please see the below sidebar for more details on the study.) We then drilled down more deeply on one nonprofit field, Child and Family Services (CFS), where M&A seems more pervasive, to understand what market forces may be driving this activity. Finally, we looked at two organizations in the CFS field that are using M&A deliberately to advance their missions. The results suggest that M&A, strategically used, has great potential to create value in the sector. They also suggest lessons for nonprofit leaders interested in pursuing nonprofit M&A and for funders interested in exploring how they can support nonprofit mergers as a philanthropic avenue with high potential for social impact.

We do not believe that M&A presents the same level of opportunity throughout the nonprofit sector. Our research suggests that certain fields are characterized by factors that make them more suited to M&A activity; in fact, more M&A activity is taking place in these fields. We will discuss this in the next section of this article and then offer brief profiles of two organizations that have used M&A strategically. Finally, we’ll offer our views on what funders, nonprofits and other stakeholders can do to foster M&A in which the highest possible expectations are realistic goals.

We evaluated 11 years of merger filings in four states: Massachusetts, Florida, Arizona and North Carolina, and found that more than 3,300 organizations reported engaging in at least one merger or acquisition between 1996 and 2006, for a cumulative merger rate of 1.5 percent (number of deals divided by average number of organizations for 11 years). Importantly, this number does not include joint ventures or partial integration (such as combining back-office operations), nor do we believe it includes more complex approaches to merging, such as asset/contract purchases, where one organization shuts down, and the remaining organization purchases its assets and assumes its contracts.

This rate may seem low compared to the perceived ubiquity of M&A in the for-profit world, but it is not. The comparative cumulative total in the for-profit sector is a close 1.7 percent. This is because the vast majority of both nonprofits and for-profit companies are relatively small, engage in M&A at similar rates and don’t generally make headlines. However, there is a striking divergence in M&A rates when you compare large nonprofits (with budgets greater than $50 million) with their for-profit peers: The rate of mergers and acquisitions among the larger nonprofits drops to just a tenth the rate of M&A in larger for-profit companies.

What “Market” Characteristics Encourage Strategic M&A?

"Market" Characteristics Favorable to M&A Activity

- Large number of nonprofits with many small players

- High degree of competitive pressure:

- Variable performance that is measurable

- Impersonal funding sources

- Barriers to “organic” growth:

- Asset intensive

- Importance of local brand

- Saturated market

- Highly regulated environment

Child and Family Services provides a good example of a nonprofit field that seems particularly suited to M&A activity and, as such, is fertile ground for strategic M&A. CFS is a nonprofit ”market” encompassing a diverse array of services including foster care and mental health, and has expenditures of approximately $70 billion annually. Our research indicates that while the 11-year overall cumulative M&A rate is 1.5 percent, the comparable rate in CFS (based on Massachusetts data) is 7.1 percent. Why is the rate of M&A higher in CFS, and what might this tell us about where else M&A might be a strategic option for nonprofits?

First, like many nonprofit fields, CFS contains a large number or organizations and is fragmented by geography and type of service. There are approximately 40,000 nonprofits, most with operating expenditures under $100,000 per year.

Second, organizations in this market are facing real competitive pressure. For one there is pressure to improve. These pressures exist because the results of nonprofits in this space vary considerably, and metrics exist that allow for comparison of performance between one nonprofit and the next (e.g., percent of youth returning to state custody). For another, the funding sources for CFS nonprofits are relatively impersonal: approximately 85 percent of all funds come from government. Unlike individual donors who often have deep personal involvement in their charities, state governments are increasingly looking for one-stop contracting, which increases pressures on organizations to grow and makes smaller organizations less viable.

Finally, there are barriers to organic growth in the CFS market. Consider:

CFS is a relatively saturated market. There are no significant numbers of youth without access to some services. Just as access to schooling is a right of every child, the core CFS services are not “optional,” and some type of provision (not always ideal) already has been made for children in need. In fact, in many states there is an excess of capacity (e.g., number of beds in residential facilities).

The market is asset-intensive on several fronts. It takes a long time to build networks of providers (training foster parents, for example). And it takes time and a great deal of fundraising to build the facilities through which many services are delivered.

Local ”brand” matters a great deal. CFS nonprofits are providing very critical and sensitive services to high-need youth, predominantly locally, and the beneficiaries (children and their families) want well-known, well-regarded entities, as do any referring organizations that are responsive to the local community. State and local agencies, which provide most of the contract funding for CFS, have similar priorities. Further, the definition of “local” can sometimes be very narrowly defined. In large metropolitan areas, for instance, local literally can infer a neighborhood.

Related to the above, this market is highly regulated by the government, which dictates how services are provided; how staff members need to be educated, trained and certified; what reimbursement rates apply; and how facilities need to be licensed. Licensing and accreditation vary based on services and geography, and all of this training and compliance can be time consuming and expensive.

Not every field that is suited to strategic M&A activity will have the same mix of defining characteristics as CFS. But our research suggests that some subset of these characteristics likely will be necessary for M&A to be a strategically viable tool.

Importantly, even in fields where M&A is strategically viable, it isn’t necessarily being used strategically. When we interviewed people involved with 29 M&A deals in the CFS space, we found that the majority of the deals were based on looming financial pressure or a vacuum in leadership at an organization. The strategic rationale was not what inspired the merger. Rather, it was articulated afterwards.

"The question facing a nonprofit should not be, 'Do we or do we not pursue M&A?' but rather 'How do we best fulfill our organization's mission and strategy to be effective, and is M&A a better option than other alternatives?'"

Patrick Lawler, CEO of Youth Villages, and one of those interviewed, helped to explain why. Youth Villages, the largest private provider of services to emotionally troubled children in the state of Tennessee, has completed a number of M&A deals to positive effect. But as Lawler explained to us, there are few supports to help nonprofit leaders identify valuable opportunities. For example, in the for-profit world, investment banks pitch merger ideas to company leaders. The closest equivalent in the nonprofit sector, he says, is when an executive search firm contacts you because another nonprofit CEO is retiring. This is a telling example of how nonprofit leaders, to date, have had to seek strategic M&A through unlikely avenues. Even in fields that clearly have potential, it’s difficult to find what you need in order to be strategic.

What are the stakes? Mergers are difficult enough when they are strategic and well-evaluated. They are all the harder when they are reactive and involve at least one distressed entity. While it is possible for a nonprofit to salvage a well intentioned peer organization or even stumble into a relationship that furthers your own nonprofit’s mission, this is often not the case.

The types of strategic benefits that nonprofits should seek are:

- Quality improvements in existing services (improved programs, training, supervision, etc.)

- Improved efficiency in existing services (better utilization of assets, reduced overhead, etc.)

- Increased funding (access to better fundraising capabilities, brand or new relationships)

- Development of new skills (programmatic expertise, broader leadership team, etc.)

- Entry into new geographies (overcome local barriers that are regulatory, community relationship, etc.)

The salient point is this: Nonprofit leaders of strong organizations in sectors that possess some or all of the characteristics noted above should move beyond the question “Do we or do we not pursue M&A?” and ask instead “How do we best fulfill our organization’s mission and strategy to be effective, and is MM&A a better option than other alternatives (organic growth through competition, partnerships, etc.)?”

Case in Point: Arizona’s Children Association and Strategic M&A

The Arizona’s Children Association (AzCA) provides a good example of a nonprofit that has pursued M&A strategically and realized substantive value from doing so. Fifteen years ago, AzCA was a $4.5 million organization, focused primarily on offering residential services in Tucson. As they looked to the future, AzCA’s leaders realized that they would need to modify their mission to have the kind of impact they wanted. As Fred Chaffee, AzCA’s president and CEO, put it, “We were primarily a residential treatment organization, and we didn’t have any services in primary prevention and early childhood work. From a mission perspective of protecting kids and preserving families, we needed to be serving kids earlier to give families the tools and reach kids before they arrived at residential services."

But AzCA didn't have the staff expertise, donor relationships or “brand” to build a new effort to serve families. So 10 years ago, AzCA acquired an organization that did, marking the beginning of a rapid, strategic expansion through M&A. Six acquisitions later, AzCA has grown into a $40-million state-wide nonprofit with a broad continuum of care for children and their families. This growth did not just come from the “purchase” of other organizations. Each acquisition allowed AzCA to add new services and skills, and to spread them to every office and program across the organization. Then, once the organization achieved “critical mass” in a given area, it engaged in competitive bidding to further organic growth. (Critical mass, according to Chaffee, “means more than just numbers of people; it’s reputation, community and brand awareness.”) But all of this rested on the success of AzCA in using M&A to gain footholds in new services, geographies and beneficiary populations.

“We might have been able to enter new service areas by ourselves, but I think it would have been a much slower process,” reflects Chaffee. “We didn’t have the brand awareness; we didn’t have the contacts nor the contracts in those areas, and so the idea was to buy an existing entity that had good brand awareness, good funding sources and the people in place at a level that was relatively small but upon which we could build… [By] acquiring these providers and keeping their names, we immediately had credibility in those services and in the communities in which they operate.”

Arizona’s Children Association’s approach has proved prescient, as the trend in recent years has been to move more children from residential to out-patient or in-home care. As a result, AzCA’s diversification has positioned the organization well to weather the corresponding changes in funding priorities.

Arizona’s Children Association’s Key Questions for Initial M&A Evaluation

Strategic fit with services

1. Does it fill a gap in AzCA’s continuum of services?

2. Does it allow AzCA to become involved in services that meet the emerging needs/trends of the agency?

Strategic fit with geography

3. Does it provide critical mass in a rural area?

4. Does it enhance AzCA’s critical mass, whether in urban or rural areas, by adding substance to vulnerable programs?

Strategic fit with AzCA brand

5. Does it enhance AzCA’s marketability, our reputation, and our branding efforts?

Organizational fit

6. Are the missions, visions and cultures of the agencies compatible?

7. Does it strengthen AzCA’s Board?

Financial impact

8. Is the merger/acquisition fiscally viable?

9. Does it enhance AzCA’s ability to fundraise?

10. Does it post a short/long-term financial risk to AzCA?

Importantly, as AzCA has gained experience with M&A, its leaders have integrated the topic into their discussions about strategy. Five or six times a year, the management team convenes to discuss when and where the organization should grow, and if there are any potential M&A candidates to evaluate as a means to achieving their goals. Arizona’s Children Association’s leaders also have developed a robust internal capability with staff members seasoned in vetting and integrating acquisitions, and solid benchmarks on the cost/benefits of merging, which they can use to raise funding for merger related expenses. Arizona’s Children Association probes any merger possibility with a set of 10 key questions (listed in the accompanying box) that its leaders use as a high-level filter to assess how well a candidate organization fits with AzCA’s strategic goals in terms of service, geography and brand. These questions also assess organizational fit and financial impact.

Once a candidate has passed this test, AzCA deploys a “swat team” of 10 internal staff representing finance, clinical staff and programming, IT and HR that meets with their counterparts when a merger or acquisition is being seriously considered. This group has developed a template used to identify both the costs for undertaking a merger and the cost efficiencies from supporting it. Arizona’s Children Association’s leaders have used these figures as an aid in raising the funds to support several of its most recent deals. With the financial case in hand, Chaffee says, he can go to foundations and say, “You have always talked about more efficiency in the nonprofit sector, less administrative overhead and more direct services. Here’s what’s going to happen with this agency and AzCA if we merge.”

Finally, AzCA also deploys this team during post-merger integration, understanding that the majority of the work—and the greatest challenge to ensuring a successful merger—stems from joining two cultures.

Arizona’s Children Association’s leaders see the organization’s strength as an M&A partner as essential to its ongoing M&A efforts. Chaffee says, “The biggest fears as a CEO or board member when you get acquired are, ‘I’m going to lose my sense of identity and I’m going to lose my mission.’ We have people on the AzCA board who represent every acquisition, and we have two of the five former CEOs still on staff. When we go in to have an initial discussion, we say: ‘Here are the names of former CEOs who either worked for us or in the community of agencies we acquired.’ They don’t sugarcoat it, but they give positive feedback and help to allay those fears.”

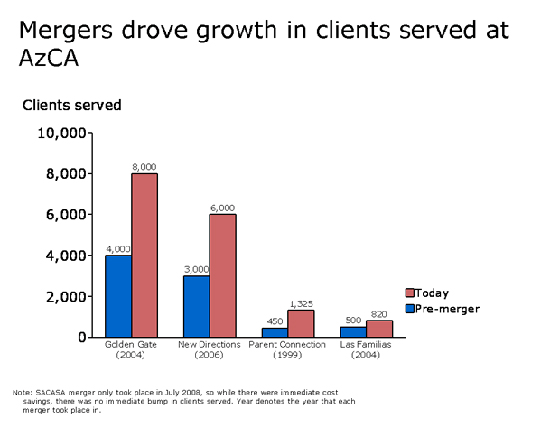

Arizona’s Children Association has used M&A to enter new service areas, new geographies and achieve critical mass to grow more competitively. Excluding (for the moment) its two most recent mergers, both less than a year old, AzCA has been able to expand the reach of each of its acquisitions (see exhibit below). What these numbers don’t capture is the increase in quality that has come from sharing experiences and the unique expertise each new addition adds to the whole.

Says Chaffee: "We now train adolescent therapists in lessons from our early-childhood acquisition, and all of a sudden, they can see where a teenager got stuck because of a trauma at age 2 and are better able to figure out what to do about it."

While cost-savings were not the strategic goal of AzCA’s M&A efforts, its growth in scale and successful integration of each new organization have allowed it to reduce cost per beneficiary from 11 to 40 percent (see exhibit below).

The Experience of Hillside Family of Agencies

Hillside Family of Agencies (Hillside), a $125 million provider of a broad range of child welfare services in New York, provides another example of strategic M&A. Ten years ago Hillside provided a range of child welfare, mental health and safety services that were predominantly residential to beneficiaries throughout the state. But the nonprofit’s leaders recognized that they would need to expand the organization’s range and reach in order to remain financially healthy and stay abreast of market demand. To that end, they began to explore M&A opportunities. The result? Over the past 10 years, the organization has engaged in five M&A deals and, in the process, doubled its size. Hillside has added a number of services to its roster, and it is now a primarily community-based (non-residential) provider. It serves more than 7,000 children and families throughout the state, under eight organization “brands.”

The ability to win access to new markets through existing brands has been a critical factor in Hillside’s use of M&A. As Clyde Comstock, Hillside’s chief operating officer (COO), put it, “You really need to be perceived as local to have any chance of winning business. The way we do this is to structure a formal partnership with another player locally and preserve its identity. You have to have a big win for both parties in order to come together. We are generally able to help them enhance their performance, access a broader continuum of services and leverage our back office.”

Hillside’s acquisition four years ago of a small residential treatment program for youth with harmful sexual behaviors provides a good illustration. Hillside wanted to expand its continuum of care to include this service, and the nonprofit in question was located in a geography where Hillside had no presence but wanted to grow. The smaller organization had skilled staff, but its major government funding agency was unhappy with its fiscal performance, and the organization’s board was under pressure to address the issue.

As Comstock explained, “The key question for us was, ‘Can we operate this successfully—both programmatically and fiscally?’ If we determined that the answer was ‘yes’ we knew it would be a lot quicker to take [them] over than to try to build something from scratch. If we tried to come into the market ourselves, we’d have to make a big investment in a new residential campus, build a local board, and build new funding and contracting relationships, which would have been almost prohibitively expensive and time consuming. Plus, we knew that if we didn’t take advantage of this opportunity somebody else would, and then we would be competing against them and be back at square one trying to develop our own presence there.”

After a due diligence process, Hillside’s leadership team did decide that the answer to that key question was “yes,” and the organization pursued the acquisition. The deal involved renegotiating the smaller nonprofit’s contract with the state agency providing funding in order to significantly improve its reimbursement rates. Hillside’s leaders also invested heavily in the smaller organization’s facilities to improve every building and bring it up to required standards.

As Comstock notes, “M&A is a strategy we regularly consider as a means to fulfill our long-term strategic plans for growth, and we deliberately cultivate a reputation for being able to work with other organizations to help them improve their services as they become part of our family of agencies. We want organizations joining us to see that the brand and value for children they worked so hard to create doesn’t go away when we merge. If anything, it grows.”

Of note: Fred Chaffee worked at Hillside before joining AzCA, which is a telling example of how, to date, an appreciation for and understanding of strategic M&A has spread slowly from one organization to another. Put another way, the experiences of these two organizations reflect the experiences of these two organizations. They do not indicate a broad spread of knowledge in the sector.

Bringing M&A to the Nonprofit Mainstream—A Call to Action for Funders

M&A is by no means a panacea for all of the many and varied challenges facing nonprofits, nor is it the only alternative for organizations seeking to grow. However, it can and should be seen as a forward-thinking strategic tool, particularly as the pressures that drive nonprofit leaders to consider M&A are increasing. As Chaffee put it, “The economic downturn we’re in is going to push M&A in a big way because small agencies dependent on just a few funding sources are going to see that funding shrink, and it will not leave them with the margins to survive.” We believe similar trends will put pressure on other parts of the nonprofit sector. (For example, think about how much education and after-school/out-of-school programming for youth is funded by local and state government budgets tied to real-estate and income taxes?)

Cocktail Parties and Head-Hunters Substitute for M&A Matchmakers

Leadership vacuums can be a catalyst for M&A, but without a proper “market of matchmakers,” M&A opportunities arise in some unconventional venues. Discussing a past merger, one nonprofit CEO reflected, “I received a call from [another nonprofit’s] board chair asking if I was interested in being their ED. I wasn’t interested, and he suggested that we think about M&A instead.” Cocktail parties and conferences also were noted as other inadvertent catalysts for M&A deals where board members from separate but similar organizations begin receptions bonding over common challenges, only to find common ground that begins M&A exploration.

Moreover, a conservative estimate from a 2006 study directed by Bridgespan founder Tom Tierney indicates a leadership deficit of at least 330,000 senior management roles in nonprofits (excluding hospitals and institutions of higher learning) within the next five years, meaning more organizations will be struggling—and competing with each other—to find strong leaders, which can be another catalyst for M&A.

Given these pressures, how can nonprofit leaders and funders ensure that the organizations pursing M&A get the most out of their deals by focusing on the strategic implications rather than on the promise of short-term relief? And how can more nonprofit leaders be encouraged to pursue M&A activity strategically to begin with?

We believe M&A can and will be more widely and effectively utilized by nonprofits if four things occur:

The strongest, highest-impact organizations begin to look to M&A as a possible avenue for fulfilling their strategies. Such organizations need to do this at least as much as organizations that are in financial distress look to M&A as a way to preserve their programs.

Foundations, government, private funders and intermediaries are willing to provide funding to support due diligence and post-merger integration, both encouraging and enabling more organizations like AzCA to make upfront investments with long-term paybacks to the organizations’ efficiency and effectiveness. Some foundations such as Lodestar in Arizona are already doing so, and seeing rewards. “We have found that the leveraged economic savings... can easily be 10 or 20... times the amount of the merger grant,” says Lodestar Chairman Jerry Hirsch, “And that doesn't include other potentially huge benefits.” Hirsch goes on to cite the increase in the quality and impact of the service provided and strengthening of the organization. In fact, Hirsch asserts that even aborted mergers can surface infrastructure issues that lead to the creation of a more viable organization. The good news is that unlike for-profit mergers, no payments are needed for an ownership stake. The costs are related to the transaction and integration.

“Because funding M&A is such a powerful opportunity for funders,” concludes Hirsch, “And because funders often lack the expertise and confidence to fund in this area, we are exploring starting a national funder's collaborative solely for the purpose of funding M&A and other types of non-profit collaboration.”

These same stakeholders invest in intermediaries, or “matchmakers,” that can create a more efficient “organizational marketplace” through which nonprofits can explore potential merger options safely and receive support in making wise decisions around: how and with which organizations to explore M&A; under what conditions to carry out a merger; and how to conduct post-merger integration to achieve success. As Comstock notes, “If I was in a small agency and thinking, ‘We’re in a dead end, and we never have enough capital even though we’re doing a good job, and I’d like to explore a way to make a better contribution,’ I would have no idea where to go except idiosyncratically through personal relationships. If there was a non-threatening way for organizations to say, ‘This is what I might be interested in’ and have introductions made by a third party, it might be very helpful all around.”

More parties take steps to educate the sector by developing a broader knowledge base about when to think about M&A, how to explore it, and—if pursued—how and under what circumstances M&A can succeed in creating its intended value.

Says Chaffee, "I would have loved 10 years ago to have some guidance on merging operations, based on what I know now."