The Pay-What-It-Takes Movement Continues to Build

In 2009, Bridgespan’s Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIR) article, “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle,” struck a nerve. Explaining the interplay between funders’ unrealistic expectations about the actual costs required to run a nonprofit and nonprofits’ contortions to comply with those expectations—often at great expense to organizational health—the piece became one of the most downloaded articles ever from SSIR’s website.

Building on earlier efforts by the RAND Corporation, Urban Institute, and others that initiated the conversation around chronic nonprofit underfunding, “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle” helped catalyze a movement that has been carried forward by a broad set of actors and has now reached every continent.

In 2016, another Bridgespan SSIR article, “Pay-What-It-Takes Philanthropy,” pushed the message further, highlighting a harmful gap between the almost ubiquitous 15 percent cap on the indirect costs funders were willing to cover and the actual indirect costs involved in providing services. In the wake of these two publications and many others, we see a promising arc of change and important signs of progress among philanthropists and nonprofits alike.

A funder collaborative digs in

Believing funders had a responsibility to engage, in 2016, Ford Foundation President Darren Walker convened a group of peer presidents of major foundations, including the MacArthur, Open Society, Packard, and Hewlett Foundations. Supported by Bridgespan, this group asked hard questions about chronic nonprofit underfunding: Which nonprofits are starved? How do we know it? The group wanted to take a deep look at their own portfolios and grantees to better understand the problem.

A chorus of voices advance the thinking—together

Bridgespan’s 2019 Chronicle of Philanthropy article, “Five Foundations Address the ‘Starvation Cycle,’” offers a timeline of more than three decades of contributions by scholars and advocates to shed light on issues related to indirect cost recovery—starting with the RAND Corporation’s pioneering 1986 report, Indirect Costs: A Guide for Foundations and Nonprofit Organizations.

So Bridgespan and the foundation presidents dug in—and the results were telling. Their grantees were prominent nonprofits, yet many were running deficits and had insufficient reserves. “I’ll never forget the moment where the foundation presidents saw the data that their own grantees were struggling,” says Bridgespan Partner Jeri Eckhart-Queenan. “Seeing the contours of the problem so vividly, they switched into action.” That game-changing data was summarized in the 2017 SSIR article “Time to Reboot Grantmaking.”

The foundation presidents met for three years until they aligned on a menu of solutions for funders. Then they invited others to join them. Seven more funders jumped on board, forming Funders for Real Cost, Real Change (FRC), a collaborative of 12 large private funders. By the end of 2021, nine of their members reported meaningful changes, including increasing or removing caps on indirect costs, increasing their proportion of general operating support grants, and helping staff better understand grantee financial health and fund accordingly.

Notably, when the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation analyzed the indirect costs of 130,000 organizations, it found that minimum indirect costs for a financially healthy organization are, in fact, 29 percent. Accordingly, it nearly doubled its indirect cost rate, moving from 15 to 29 percent. The Ford Foundation has announced similar action, committing to increase its indirect cost rate from 20 to 25 percent beginning in 2023.

“We all need to move beyond the rhetoric to changing policies and practices. Go beyond a fixed-percentage overhead limit. Invest in multiyear general operating support. Invest in local leaders, especially women and girls. And invest in your partners’ organizations.”

Funders embrace more flexibility

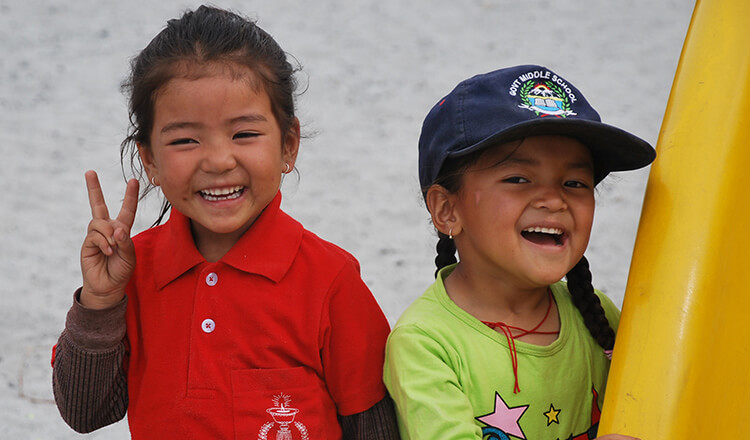

For its first eight years, the 17,000 ft Foundation lived hand to mouth as it tried to serve children in India’s Himalayan region. In 2019, the A.T.E. Chandra Foundation paid for a year-long engagement for 17000 ft with Atma, an organization that builds the capacity of education NGOs. “I wasn’t even aware that there were organizations that worked with nonprofits on organizational development,” says 17000 ft founder Sujata Sahu. “You don’t know what you don’t know until you start this journey.” Photo: 17000 ft Foundation

Beyond increasing indirect cost rates on project grants, we also see more funders providing flexible multiyear grants.

“Flexible multiyear grants increase impact and build strong nonprofit organizations,” says Eckhart-Queenan. “While project-restricted grants play an important role, they are overused and often underfunded. Flexible multiyear grants enable grantees to invest as needed in their own capacity and to be agile and nimble when necessary.”

Today, flexible multiyear grants constitute the majority of grants at the Ford, Hewlett, and Oak Foundations.

“There is an increasing recognition that grantees generally are closer to communities, closer to the work, and in strong positions to direct their funding to its most important uses,” says Bridgespan Partner Gail Perreault, who sees a connection between the Pay What It Takes movement and the growth of trust-based philanthropy. Trust-based approaches, such as providing grantees with flexible multiyear support, are also resonating with high-net-worth individuals who have historically struggled to deploy large amounts of wealth toward social change.

Room to GROW

Bridgespan’s data around nonprofit underfunding hit EdelGive Foundation CEO Naghma Mulla hard. “We all know we do not pay for critical costs, but to say that 83 percent of organizations did not have access to such funding for organizational development was heart wrenching,” says Mulla. In 2021, EdelGive launched the Grassroots Resilience Ownership and Wellness (GROW) Fund, which will give 100 nonprofits $50,000 each for the next two years. This money is specifically designated to cover indirect and organizational development needs.

The signposts of change are global

While initial Pay-What-It-Takes efforts were largely focused on US-based funders, global action has been growing—spurred on by COVID and the imperative to distribute funds quickly. Recent efforts corroborate that the funding gap exists everywhere, underscoring the need for widespread policy change.

For instance, a 2020 FRC-commissioned Humentum study of NGOs in 10 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe found that most funders provide inadequate coverage of their grantees’ indirect costs, with significant negative consequences for the organizations’ health.

Over 1,000 organizations around the world have signed on to Catalyst 2030’s Shifting Funding Practices letter, which calls on funders to change their practices—by, first and foremost, giving multiyear, unrestricted funding.

In India, nonprofits find their voices

In India in particular, momentum is building. Bridgespan launched the Pay-What-It-Takes India Initiative in 2019 to address the chronic underfunding of NGOs in India. Bridgespan research indicates 83 percent of Indian NGOs are unable to pay for the core functions that would make them resilient organizations.

The Ford, Gates, Children’s Investment Fund, EdelGive, and A.T.E. Chandra Foundations as well as the Forbes Marshall Group are currently working with Bridgespan to build resilience in the Indian NGO sector. Omidyar Network India also helped seed the initiative. The work started none too soon: almost immediately, COVID intensified nonprofits’ stark needs. “Although NGOs’ work was all the more important during the pandemic, many were shutting down or significantly paring down their work due to funding constraints,” says Pritha Venkatachalam, Bridgespan partner and co-head, Asia and Africa.

While Bridgespan India’s work with funders mirrors efforts in the United States, it is breaking exciting new ground on the nonprofit side of the equation. “The first thing we realized was that every intermediary working with nonprofits had their own set of tools,” explains Bridgespan Principal Shashank Rastogi. The Bridgespan team collaborated with leading intermediaries to devise a single toolkit that identifies key organizational capabilities, such as fundraising, monitoring, learning, and evaluation, and breaks them down into sub-elements. The toolkit provides step-by-step instructions for developing these capabilities, showing what they may look like in early and more evolved stages.

In addition, Bridgespan identified three archetypes of funders—those focused on programs, those that adapt their funding on a case-by-case basis, and those focused on building stronger NGOs—so nonprofits can target their requests more precisely.

The A.T.E. Chandra Foundation hosts a workshop for NGO leaders in India to build their core capabilities and financial resilience. Working with A.T.E. Chandra Foundation helped Pritha Venkatachalam, Bridgespan partner and co-head, Asia and Africa, understand that in addition to continuing to work with individual foundations and NGOs, we needed “to also do something at the sector level to create a movement that makes NGOs stronger and more resilient.”

Photo: A.T.E. Chandra FoundationBridgespan will soon begin workshops to help nonprofits use these tools. In the meantime, the conversation has taken off in India, with many funders and nonprofits now actively talking about organizational capacity building. “In the beginning, the feedback we got from nonprofits was, ‘It’s an important issue, but no one talks about it,’” says Rastogi. “Now, the need has been established. A lot more nonprofits and funders are talking about building trust between funders and NGOs.”

(This article was last updated in 2022.)

Notes

1. Funders for Real Cost, Real Change (FRC), which grew from the Bridgespan-supported funder collaborative, was carried forward by BDO FMA. In addition to the original five foundations, the group includes Arnold Ventures and the Conrad N. Hilton, James Irvine, Oak, Robert Wood Johnson, Rockefeller, and W.K. Kellogg Foundations. Funding for Real Change is now available to all as a public resource.

2. Rick Eden et al., Indirect Costs: A Guide for Foundations and Nonprofit Organizations (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation 1986).