Without sound management practices, even the most successful nonprofit will be unable to sustain, let alone increase, its impact over time. And yet, when Bridgespan consulting teams surveyed senior staff members at 30 nonprofits, the respondents consistently rated their organizations much higher on leadership dimensions like developing an overall vision than on management dimensions like making trade offs and setting priorities in order to realize that vision. Many nonprofits appear to be strongly led, but under-managed.

Why is this so? In our work with the leaders of more than 100 nonprofits, we’ve heard the same answer time and again: The environment in which they operate often reinforces visionary leadership at the expense of management disciplines. Passion, coupled with the ability to make a compelling case for a cause, drives fundraising and helps leaders attract and motivate staff and volunteers. But nonprofit leaders generally are not recognized or rewarded for their managerial qualities.

The signs of inadequate management are easy to spot: Staff members are confused about their roles and responsibilities. Out-of-control finances, arising from an inability to set and operate within a sustainable budget and /or inadequate financial systems, threaten to overwhelm the organization’s focus on impact. But while it’s not difficult to recognize the problems—and to see that more effective management practices are needed—getting the job done is no small feat.

What can be done? We recently discussed this topic in depth with a select group of leaders whose nonprofits are purposefully navigating the path towards stronger management. Our goal was to better understand this apparent rift between leadership and management, and to learn how these leaders have been working to overcome it. As the conversations progressed, it became clear that these leaders had each used essentially the same three levers to ensure that their organizations appreciate, build and sustain strong management practices. They each worked hard to clarify their organization’s strategy; they established meaningful metrics with which to assess progress; and they made it a priority to assemble a balanced team at the top. They also made a point of engaging the organization to adapt these changes in ways that were consistent with – and animated by – the overall vision.

Taken at face value, the three levers sound straightforward—even obvious. And in a theoretical sense, they are. But applying them in the context of nonprofit leadership is difficult. This article will explore how the leaders of a small group of nonprofits—Teach for America (TFA), Communities in Schools (CIS), the Partnership for Public Service, the Corporation for Supportive Housing, and Jumpstart—have used these levers to strengthen their organizations.

Understanding the Tension Between Leadership and Management

Before exploring the three levers in more detail, it is important to be clear about the differences between leadership and management, and the inherent tension between the two roles. The sidebar “Leadership and Management: What’s the Difference?” (found at the end of this article) provides a brief explanation of the differences between the two; Rob Waldron’s early experiences as CEO of the youth-serving Jumpstart organization illuminate the tension.

Upon joining Jumpstart, a national network focused on mobilizing college students to provide tutoring to young children in Head Start programs, Waldron quickly realized that the fast-growing organization was losing its most precious resource—talented, committed people—through turnover. As he put it, “People were working so hard to muscle everything. They were quitting because it was so tiring to keep up with the complexity.” Waldron knew that Jumpstart needed to bolster its management practices. Simultaneously, however, he was learning firsthand about the tension between leadership and management in the sector. “[I told funders,] ‘I want to be the best manager of a nonprofit in Boston, and I want us to be the best managed nonprofit in America,’” he said. “Based on my for-profit experience, I thought that strong management was what people would seek and want to invest in. But no one gives a &$#@. They don’t make the decision that way. It’s not the thing that drives the emotion to give.”

As Waldron came to realize, the qualities that make for strong leadership are critical to an organization’s ability to attract money and talent. The capacity to share the mission in compelling ways is absolutely vital to success on these dimensions. The challenge, then, is to not only deepen management capabilities, but to do so without diminishing the mission-based leadership aspects of the organization.

Getting to Strategic Clarity

The first and most important lever utilized by the nonprofit executives we interviewed is achieving strategic clarity. We say “most important” because the other two levers depend upon this one; in practice, however, any one lever without the other two is not effective.

Achieving strategic clarity means answering, in very concrete terms, two questions that are core to a nonprofit’s mission: “What impact are we prepared to be held accountable for?” and “What do we need to do—and not do—in order to achieve this impact?”

Developing this clarity is a critical step in aligning the organization’s systems and structures around a common objective. It also enables the distribution of decision-making authority beyond the executive director, as decisions that once required judgment calls by the leader can be made by a broader group aiming towards an agreed upon set of outcomes.

Getting to strategic clarity is not synonymous with developing yet another strategic plan; too many nonprofit leaders have had the experience of developing strategic plans that consumed large amounts of their senior teams’ time, only to see them end up on a shelf because they couldn’t be implemented or were quickly outpaced by events. As Wendy Kopp, founder and CEO of Teach for America, remembers concluding at one point in a strategic planning exercise, “I am not going to read another overly detailed plan that tries to lay out what every part of the organization is going to do for several years. This makes no sense. We are going to forget all this planning, and we are going to come up with a few priorities and very clear goals.”

At Teach For America, the question about accountability came down to: 1) attracting a new source of teachers to underserved public schools who will have a meaningful impact on their students’ achievement (with one measure being having children make one and a half years of progress in one year of school) and 2) providing an ever-expanding force of leaders who continue working—inside and outside the education system—to ensure educational opportunity for all (which links tightly to measures such as alumni assuming leadership roles in schools, government, and other nonprofits). The fact that everyone at TFA aligned around these answers not only provides stability for the organization’s strategy but also makes it easier to answer the question of how to achieve the desired impact by setting priorities, establishing performance measures, and making tradeoffs.

TFA, like many successful nonprofits, has often been urged to expand its scope and take on new tasks, such as opening and running charter schools. But the organization increasingly has focused on what it considers “core,” thereby holding to the theory of change that has helped it achieve its impact thus far. “I’m so clear about it,” Wendy Kopp notes, “and part of my role is to make sure everyone else is clear about it. It’s hard to describe how many times, even in a day, I end up saying, ‘But that wouldn’t make sense given our theory of change.’”

Importantly, getting to strategic clarity is not about dumbing down what you are trying to do and how you are trying to do it, so that you can convey it to funders in the proverbial elevator speech. The Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH), which has helped catalyze a sea-change in the way that federal, state, and local funders and providers think about serving the homeless, especially the hardest-to-serve chronically homeless, provides a compelling example on this point.

CSH has operated for some time on three distinct levels: conducting advocacy at the state and federal levels to bring about policy change; building capacity among organizations in the field, so that they become more effective developers and operators of supportive housing; and providing financing and technical assistance on a project-by-project basis. As Carla Javits, the former CEO recounts, at one point in CSH’s development, “Several members of the board really pushed us on the question of which of the three lines of business would be most important. Which one is the most critical, the most central to our work? And we went back and really talked that through.” Eventually, they concluded that they really couldn’t prioritize one above the other. “The beauty of CSH, was the interaction among the three,” Javits recalls. “But that forced us to think about it…[and] to better articulate our theory of change.” The point is to get to what Oliver Wendell Holmes called “simplicity on the far side of complexity,” or the simplicity that reflects deep and sustained thinking about the focus of the organization’s work, so that it hangs together on its own and in the broader context in which it is operating.

Anchoring Strategic Clarity in a Few Key Metrics

Once a nonprofit has achieved strategic clarity, homing in on a small number of key metrics can be a powerful way to keep everyone in the organization focused. In effect the metrics become the shorthand to measure both the fidelity of the implementation and the ultimate outcomes.

At Jumpstart, Rob Waldron zeroed in on three metrics: the number of kids served; the gain per child; and the cost per tutor hour. Once those three measures were in place, the organization was able to flag unproductive variations across sites, drive increased growth and effectiveness, and lower unit costs. As a result, when it became apparent that one site was consuming twice as many resources as another to serve the same number of children with the same results, few people questioned the need for change—or the desirability of spreading best demonstrated practices throughout the network.

As the Jumpstart example illustrates, the key to establishing effective performance measures is to focus on ones that will be highly motivating because they are so clearly aligned with the organization’s mission. Unfortunately, external pressure for transparency, accountability, and demonstrated results does not always result in the establishment of meaningful performance measures. Instead the tracking and reporting become an exercise in process, make-work that the organization has to do to satisfy its external stakeholders.

Sadly, nonprofits that do not push beyond this thin way of thinking about metrics are missing a powerful tool for managing—and improving—performance. At Teach For America, for example, accountability and measures were central to instilling a results-oriented culture. As Wendy Kopp observes, “Our people are so focused on what it is that we’re trying to accomplish from a social impact perspective, that it leads them to be really open to the idea that this is not about us—it’s about getting to the goals more quickly.”

For all their appreciation of the power of metrics, however, nonprofit leaders we have worked with and spoken to also confess to being ambivalent about them. The ambivalence stems in part from the ongoing challenge of finding meaningful measures to track and reflect the full scope of what their ambitious organizations are trying to do. The Partnership for Public Service, for example, is dedicated to improving the effectiveness of the federal government, and yet the government agencies themselves typically have no clear and compelling benchmarks to assess their own effectiveness. One of the Partnership’s goals is to help the government create and refine these indices. But in the interim, its own commitment to measuring its performance is hard to make operational. Max Stier, the executive director, observes: “We certainly don’t have a single metric that everything can be boiled down to, like there is in the for-profit sector.” At the same time, however, the effort to define the right metrics is an ongoing topic for the group. “[Although we haven’t yet gotten to closure,] every conversation we have talks about metrics in some form or fashion.”

Building and Aligning the Team

Augmenting the experience and capabilities of the senior leadership team is often the most visible sign of change in organizations that are becoming more strongly managed. While there are a variety of ways of going about this, one of the most common is naming someone with managerial experience and a mindset oriented around systems and processes as the organization’s second-in-command. At CIS, for example, Bill Milliken, the visionary founder, long-time CEO, and current vice chair, elevated a protégé with an aptitude for management concerns—Dan Cardinali—to become president of the organization. The two now work in tandem, with each exercising both leadership and management. When one of the organization’s state directors pushed back on some of the changes that the top leadership team had determined were necessary, for example, it was Milliken, not Cardinali, who weighed in, saying, “This is where we need to go. This is what is going to make us effective to serve more kids and leverage more resources.”

At Teach For America, Wendy Kopp initially took a different tack. After TFA’s tumultuous but successful start up phase, she initially considered handing things off to a new leader, “because what did I know about how to manage this, really?” But then she decided that TFA would be best served by her staying on—and shoring up her own weak points as a manager. “I just thought I’d better learn how to do this stuff. I think it is just so learnable.” However, she is also quick to acknowledge that she has hastened her education by bringing in colleagues with private-sector experience who have established and help drive best practices on multiple management fronts. “Everyone’s always asking me ‘Who are your mentors?’ and ‘What is the board’s role?’ The honest truth is I’ve learned so much from the people who’ve worked here and pushed us in various ways…And that’s really what’s driven our evolution.”

More recently, Kopp has brought in a chief operating officer to whom she has turned over much of the operational responsibility for TFA. She observed that, “The reality is that while I became decent at management and got things headed in the right direction, the new COO is better. Beyond his natural abilities, he also brings an experience base that I simply don’t have. At this point in our development—given our size and complexity—that has made a huge difference.”

The flip side of augmenting the team with individuals who possess needed skills is letting go of employees who may be passionately dedicated to the organization, but who are not able to contribute to the level they should. Here the dynamics of the nonprofit sector can make decisive and often necessary action especially difficult.[1] As one leader told us, “There is a woman on the staff right now whom I am struggling with. She will say, ‘I just want to dedicate my life to this organization.’ And when she throws that at you, she’s basically saying, ‘You are going to jeopardize my happiness and my sense of meaning if you change my employment status.’” That said, this leader, like many others with whom we have spoken, went on to say that if he were to do things over again, he would move much sooner to complete both the hiring and the firing for his senior team.

While creating new roles and/or elevating certain positions can reinforce a new emphasis on management, many leaders point to a necessary complement: explicitly connecting these individuals with the mission-related work of the firm. After Carla Javits became CEO at the Corporation for Supportive Housing, for example, she created a chief financial and administrative officer position to oversee augmented finance, IT, HR, and business-support functions. “Each of those departments got a little more beefed up under the leadership of one person who then brought all four functions together and really raised their profile.” At the same time, Javits also made a point of having her CFAO operate at the same level as the COO who oversaw all the programmatic work, thereby ensuring that “the business leadership became part of the senior leadership team of the organization.”

Similarly, Max Stier established a trusted colleague in a COO-like position shortly after founding the Partnership for Public Service, and relies on him to manage the administration, finance and HR functions—freeing Stier up to focus on the board, the press, funders, and other external stakeholders. Importantly, however, over the years, Stier and his colleague have made a point of not making a clean “Mr. Outside/Mr. Inside” split. “It’s a bad idea to have a full distinction,” Stier believes, in part because the person in the operations role has relevant programmatic expertise, and in part because he feels it’s important for him to stay in touch with some of the key internal issues.

Managing the Changing Process In Ways that Reflect the Vision

The changes discussed above—achieving strategic clarity, anchoring it in a few key metrics, and building and aligning the team—are critical. But at times, they can also appear be at odds with the vision that animates the organization. That’s why actively managing the change process—reinforcing not only why change is necessary, but also how it will strengthen the organization’s ability to sustain its impact and live into its mission over time—is an ongoing leadership challenge.

Engaging the line staff in the work of change by soliciting their perspectives is an important piece of the puzzle. In part, this is common sense, since their work often gives them the clearest view of what the issues and opportunities facing the organization actually are. Getting them involved also helps to foster the commitment and support that will be needed to sustain the changes and energize people. When CIS was establishing its new direction, for example, the senior team solicited input from all three levels of the network (local, state, and national) about the new roles and responsibilities. “We ran this very iterative process,” Dan Cardinali remembers, so that we could “create some transparency around the fact that this was a new day, and we were going to make some changes.” The Partnership for Public Service, a much smaller organization that operates in one office, generated buy-in by creating a Strategic Planning and Review Committee, consisting mostly of junior staff. The group ramps up or down as needed depending on the issues facing the organization—a development Stier views as “very, very beneficial.”

Helping people see the upside of more rigorous management practices is another critical piece of the process, not only because the pain and disruption of new ways of working always precede the benefits, but also because personal commitment to the organization’s mission is what tends to keep the best people on board. Carla Javits found this especially important when the Corporation for Supportive Housing moved to establish more effective and detailed accounting and data-reporting systems in its local offices. While the initiative was essential for the overall health of the organization, it placed a greater administrative burden on the local office leaders. Javits observes: “The questions then become, ‘Is this going to be worth it? ...What are we going to get out of it?’ [You need to] really drill down on what the payoff is, why it needs to be done—especially in a mission-driven organization.”

Initially, she emphasized the fact that better financial information would not only give the local leaders a better view into what was going on, but also help them “make [the state of play] more transparent to the people in the organization who need to know.” It wasn’t long, however, before she was in a position to share information from the new systems that could help CHS have greater impact, because “we thought X, but actually it’s Y.”

Javits also created a powerful institutional bridge between the programmatic and management sides of the organization by having the CFAO and head of finance join the regional program leaders for their recurring leadership team meetings. “In some ways it annoyed people,” Javits said of the change in process, “because the program leaders didn’t necessarily want to be spending that much time on business issues, and the business leadership wasn’t necessarily prone to spend so much time listening to program issues. But doing that made an immense difference in the organization [by fostering] mutual respect and understanding.”

Wendy Kopp noted the value of continually communicating the idea that stepped-up management practices aren’t distractions from the work—they are the work. But, at the same time, she said, recognizing and encouraging the passion that drives nonprofit work is crucial: “You need all of the systems, but you just can’t afford to lose the spirit. We have to sell our people on the idea of using data….[by] getting them to realize that focusing on their kids’ academic achievement is the greatest form of social activism, and that measuring their progress is critical if they are going to do that. [Along the way], you also need to make sure you’re not inadvertently doing things that meet the measures but don’t maximize your ultimate impact…Getting all of that right is very hard.”

Even as new practices take hold, the tension between leadership and management considerations will persist. And so it is important to be continually on the alert for symptoms that might indicate a need to adjust or renew efforts to strengthen management. As we have observed—and as our conversations with nonprofit leaders have confirmed—unforeseen challenges always accompany growth. So even if the leadership team is doing the organizational equivalent of changing its oil and filter every 3,000 miles and rotating its tires regularly, the “check engine” light is bound to come on as the odometer spins upward. Long-term success lies not in anticipating and preempting every single challenge, but in being receptive and prepared to take action when a new warning light flickers on.

| Leadership and Management: What’s the Difference?[2] |

|---|

|

In a nutshell:

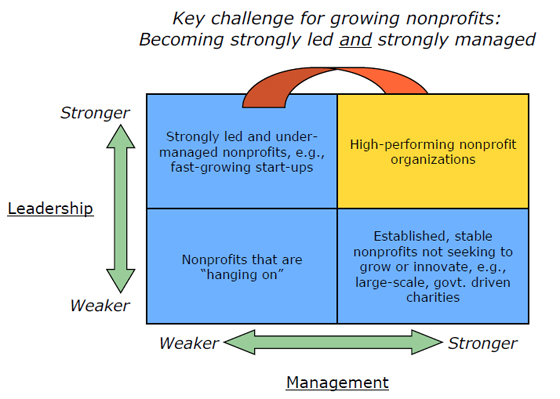

If leadership is—in John Kotter’s apt phrase—“a force for change,” then management is geared to reliably delivering the product or service of the organization amid complexity. The framework below illustrates the shift that many non-profits need to work through in order to become a high performing organization. Leadership and management need to be understood in terms of the collective capacity of an organization and not as characteristics of individual people. Although individuals may gravitate toward one or the other, all of these activities are essential if an organization is to deliver great results over time. |

SOURCES

[1] See Jim Collins, “Good to Great and the Social Sectors,” self-published monograph, 2005.