Many school district leaders, high school administrators, and teachers—particularly those in urban areas—have struggled to reduce high school dropout rates but find themselves overwhelmed by the dimensions of the problem. Consider: Research has shown that lack of preparation in elementary and middle school, long before students reach high school, is a key factor affecting dropout rates once these students are in high school. Moreover, improving the quality of teaching and learning in high school has proven to be a very difficult arena in which to make substantial progress. These challenges are further compounded by budget constraints that limit organizational capacity and by high turnover in district leadership positions. Insofar as the average tenure for an urban superintendent is a little over two years, it is easier for others in the system to lay low and avoid major change initiatives. A series of “strategic initiatives” often supersede each other in sequence, rising up and then fading in importance one year to the next.

The U.S. High School Dropout Crisis

- One third of high school students across the nation fail to get a high school diploma on schedule [1]

- For minority students, that rate falls to 50 percent.

- Every day 7,000 students drop out of school [2]

These figures are staggering; what’s more, they have profound consequences for equity and economic opportunity in the United States. When compared with college graduates, dropouts earn $1 million less over their lifetimes and are three times more likely to be unemployed. A dropout is eight times more likely to be imprisoned during his or her lifetime than someone with a high school diploma.[3]

There are, however, a few districts making notable progress towards reducing the number of dropouts and ensuring that students earn high school diplomas in a timely manner. One of these is the Portland, Oregon, public school system. This case study tells the story of how Portland Public Schools (PPS) began to have a positive impact in addressing the dropout problem over the course of one calendar year. In particular, it follows the district leaders’ actions as they moved from data and decisions to implementation and results for those high school students most at risk of dropping out as they transitioned into the 9th grade.

The district’s work is by no means complete. Moreover, the initial significant progress, visible in current data, could well be reversed if insights about what works, what doesn’t and why are not developed further and acted upon by PPS district leaders, high school administrators, and teachers. That said, the story of work that PPS did in 2007-08 to help students transition into high school can serve as a powerful example for other districts seeking to make similar strides in reducing their own dropout problems.

It is important to note that PPS’s efforts to reduce its dropout rate are part of a larger strategy to transform high school education in Portland. Thus, in the following section, we will take a step back to examine the context in which the district’s leaders began their work and the overall, multi-faceted vision they articulated. From there, the case zeroes in on the specific efforts undertaken to reduce the number of high school dropouts. Finally, it assesses the progress PPS made in the first year of implementation, and in a sidebar, presents several take-away lessons—illuminated by Portland’s experience—that other school leaders might find useful as they strive to reduce their own dropout rates.

Context and Strategy: The Overall Vision for PPS

Vicki Phillips was named superintendent of PPS in 2004. She had previously served as the superintendent of schools in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where she also served at the state-level as the secretary of education and chief state school officer. Throughout her career as an educator, going back to her days as a high school and middle school teacher in her native Kentucky, Phillips had demonstrated a deep commitment to improving the quality of teaching and learning experienced at an individual level, student by student, in every classroom.

In the years immediately following her appointment as superintendent of PPS, Phillips made a number of significant decisions that provide the context for the story below. Chief among those was establishing a rigorous, district-wide K-12 core curriculum and making a commitment to provide tailored support to every student by name. This commitment to individual students is worth emphasizing because of its ultimate importance to the success of the high school transition work.

Portland Public Schools at a Glance (October 2007)

- ~46,000 students attending Portland Public Schools

- 55 percent Caucasian, 41percent Minority, 3 percent Other or multiple ethnicities

- 16,500 high school students with a variety of school options to choose from

- 5 comprehensive high schools

- 9 small schools on four campuses

- 30+ other educational options (alternative schools)

- 1 vocational school

- 2 charter high schools

A second important decision Phillips made was to endorse the work of—and have PPS participate in—what has come to be known as the Connected by 25 consortium, a community-based network that now includes more than 40 public, private and nonprofit organizations in Portland. Connected by 25 aspires to be "an unprecedented effort that harnesses the extraordinary commitment of Portland citizens in order to connect every young person to school, work, and community by the age of 25."4 The consortium was created in 2004, when several community groups led by the Portland Schools Foundation applied for and received a grant from the Youth Transition Funders Group, a coalition of philanthropic organizations with a shared interest in creating community responses addressing off-track and out-of-school youth. Subsequently, the network received additional funding from the Meyer Memorial Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A third significant decision was to bolster the district’s capacity to support teaching and learning in the schools by augmenting the existing Office of Teaching and Learning, reorienting the district’s administrative and operational staff to view schools as their customers; and—most salient for this case—creating an Office of High Schools (OHS). Phillips charged OHS with developing and overseeing the implementation of a district-wide strategy for transforming high school education. Portland Public Schools high school administrators would all report up through this new office.

To head up OHS, Phillips tapped Leslie Rennie-Hill, who had previously served as director of program initiatives at the Portland Schools Foundation. Importantly, while in that post, Rennie-Hill had led the development of the original Connected by 25 proposal and coordinated the group’s early activities. Rennie-Hill also had recently served as the coordinator for a district-wide teaching and learning review that PPS had carried out in 2005-06 with the support of the Annenberg Foundation, so she was quite familiar with the current state of PPS high schools. Her initial focus at OHS would be building up the OHS team at the district level and spearheading the strategy development effort.

Portland Public Schools had retained consultants from the Bridgespan Group to assist with the reorientation and augmentation of the district offices to support teaching and learning in the schools in 2005-06. The district reengaged Bridgespan in January 2007 to help Rennie-Hill and the OHS team develop the new high school strategy.

Phillips also asked her chief of staff, Carole Smith, to work closely with and serve as a sounding board for Rennie-Hill and her joint OHS-Bridgespan team. Smith was relatively new to the district office but not to the problem of dropouts in Portland, as she had been the longtime executive director of Open Meadow, a successful nonprofit alternative high school that helped youth who struggled in conventional school settings continue with their education. In this capacity Smith had developed a program called Step Up that took important elements of her alternative school’s supports for students at risk of dropping out directly into PPS high schools. Like Rennie-Hill, Smith was an early participant in the Connected by 25 effort and also had served on the original Connected by 25 grant proposal team.

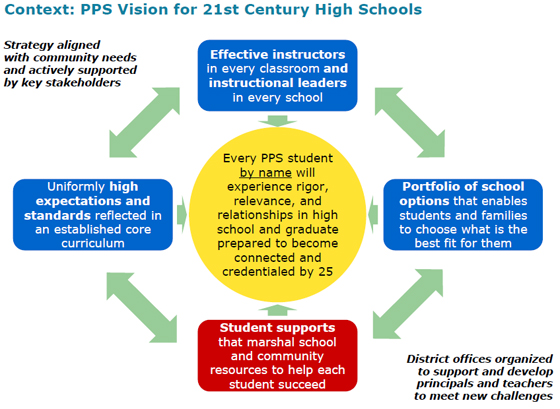

At the outset of the high school strategy development process, Phillips and Rennie-Hill articulated an ambitious vision: “Every PPS high school student by name will experience rigor, relevance, and relationships in school, and graduate prepared to become connected and credentialed by 25.” The process then unfolded in three distinct phases. An initial four-month diagnostic phase was primarily aimed at building the case for change through an analysis of current student outcomes and the underlying drivers of performance. A two-month strategy phase focused on defining what a transformed high school system capable of addressing unmet student needs would look like. The final one-month roadmap phase focused on honing the implementation and communications plan for the large scale transformation of Portland’s high schools.

The vision for Portland’s 21st century high schools, and also the framework that emerged from the strategy development process, appear below:

It was in the context of this strategic framework—in particular, the section articulating expectations for “Student Supports”—that PPS began tackling its dropout problem.

Zeroing in on the Causes of the Dropout Problem

There was a certain amount of complacency in Portland (as in many school districts) regarding the dropout issue. In large part this stemmed from standard and misrepresentative graduation statistics. The commonly reported National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) methodology for calculating graduation rates—which is also used by the Oregon Department of Education—had regularly put the PPS graduation rate at about 80 percent, indicating that one in five students was not graduating. The problem with the NCES and other calculation methods that incorporate aggregated dropout rates into their graduation rate formulas is that dropout counts tend to be under-reported, and consequently, graduation rates are inflated.[5]

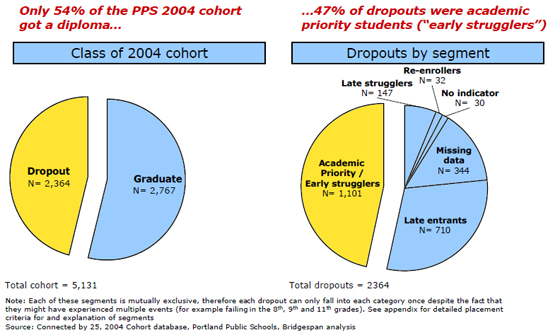

Connected by 25, however, had been able to provide PPS with more accurate—and much more sobering—data. The group had commissioned consultant Mary Beth Celio of Northwest Decision Resources to develop an in-depth analysis on the PPS class of 2004 and the dropout patterns that students in this cohort experienced. This research revealed that of any student who had ever been a member of the class of 2004, only 54 percent of the cohort (2,767 of 5,131 students) left high school with a diploma.[6]

The analysis also identified a range of indicators that were predictive of students’ dropping out. Not surprisingly, the analysis revealed that youth who were not prepared for high school (e.g. those who failed early) and those who didn’t have a continuous high school experience (e.g. those who left and returned) were more likely to drop out. More significantly, when OHS staff applied these indicators to the 2004 cohort database of individual students, they found that 99 percent of dropouts experienced at least one of the five indicators, and also that no single indicator was present for the majority of students.[7] The statistics told OHS team members that certain indicators were generally predictive of student outcomes but not in a way that would enable them to improve upon them readily.

To narrow the problem and identify the best intervention point, the OHS staff, the Bridgespan team, and members of the district’s Research and Evaluation Department (R&E) used the leading dropout indicators to go beyond the Connected by 25 analysis and create a set of mutually exclusive student segments (i.e., no student was in more than one segment) based on the first risk indicator each student experienced. Their hope was that this perspective would lead to additional insight. The decision to segment students in this way warrants elaboration because, as it turned out, it was the lynchpin to the entire subsequent initiative. Since each student was identified by the first risk indicator he or she experienced, and since there were no overlaps, the segmentation enabled the team to discern when to intervene and with whom.

The segments were:

- Academic Priority Students (APS): Students who fail to meet 8th grade proficiency in at least two (out of three) standards AND/OR fail a core course in the 9th grade[8]

- Late strugglers: Students who, at completion of 11th grade, have fewer than 15 credits (out of a total of 24 required for graduation)

- Late entrants: Students who enter PPS for the first time in 10th grade or later

- Re-enrollers: Students who withdraw and subsequently re-enroll

Two segments clearly stood out once the analysis was complete. Nearly 80 percent of the students who eventually dropped out of the 2004 cohort fell into either the “academic priority student” segment (47 percent of dropouts) or the “late entrant” segment (30 percent of dropouts). Having only two groups make up such a large part of the challenge made it significantly easier to focus efforts and strategize about how to turn around the outcomes for a majority of at-risk students. The segmentation exercise and the resulting simple data picture it provided showed OHS team members which students they should focus on given limited time and resources.

It’s worth noting that the importance of the 9th grade year that emerged through the PPS student segmentation data has been extensively documented in peer-reviewed education research. For example, Ruth Curran Neild, Scott Stoner-Eby and Frank Furstenberg have found that when an extensive set of controls (e.g. for family, aspirations, etc.) are placed on a group of students, their 9th grade outcomes still contribute substantially to the researchers’ ability to predict eventual dropout. Neil et al. conclude, “Reducing the enormous dropout rates in large cities will require attention to the transition to high school.” [9]

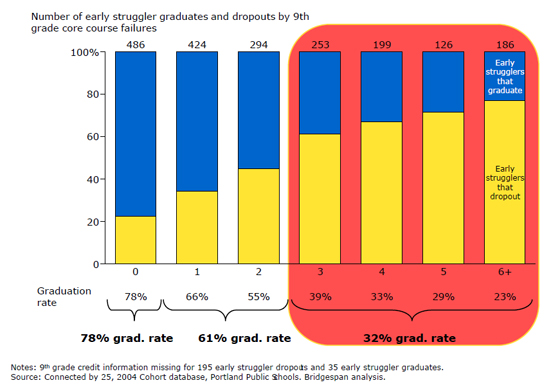

The Connected by 25 analysis, the ancillary research, and the sheer size of Portland’s academic priority group thus made focusing on the transition to 9th grade a natural place to start. The challenge was figuring out which students were truly at the highest risk of dropping out. While the students whose performance in 8th and 9th grade had flagged them as high dropout risks represented about 50 percent of all dropouts, only about 50 percent of that group would eventually drop out. Why did some of these academic priority students succeed and others fail—and how could a cost-effective set of interventions be set up to support this population?

To answer that question the OHS team looked even more closely at this group. Since the segment graduation rate was 50 percent overall, the only meaningful risk indicators would be those that decreased likelihood of these students graduating to less than 50 percent.

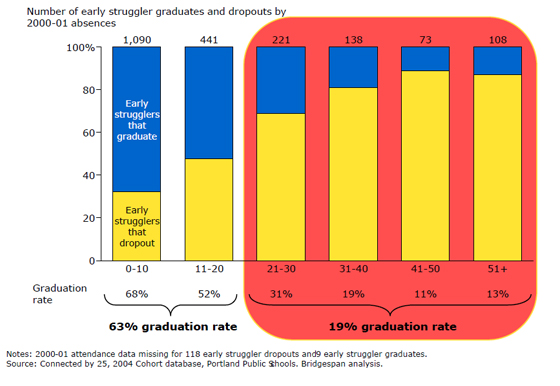

This additional work revealed two clear indicators differentiating the academic priority students who graduate from those who drop out: the number of courses the students failed in 9th grade; and the number of unexcused absences they had. As displayed in the chart below, the analysis showed that academic priority students who did not fail any core courses had a 78 percent graduation rate, and those who received a D or an F in one or two core courses had a 61 percent graduation rate (both higher than the 50 percent segment average). Those who received Ds or Fs in three or more core courses, however, had only a 32 percent chance of graduating.[10]

Similarly, as indicated in the next chart, academic priority students who had 20 or fewer absences had a 63 percent graduation rate (higher than the average), whereas those who had 21 or more absences had only a 19 percent chance of graduating.

Making the Commitment to Act

By May 2007 Phillips, Smith, Rennie-Hill and the OHS team knew how to identify a substantial portion of likely dropouts before they finished 9th grade. They also had an increasingly clear sense of what supports would be needed to help these students stay in school and be successful. Even with that powerful knowledge, however, the possibility of inaction loomed large. Just as the analysis was finalized, PPS began a period of transition. After three years of guiding the district through a series of major changes, Superintendent Phillips announced that she would be leaving Portland to head the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Education Division. Additionally, district leaders and school administrators thought it was too late in the year to begin a new initiative. High school graduation was only a few weeks away for PPS seniors, and shortly thereafter teachers and then school administrators would be starting their summer vacations. Finally, even with the know-how, it was not clear that the incoming academic priority students could be identified: a failure in the state’s computer systems meant that data for one primary indicator wouldn’t be available for months.

Several forces pushed back against this inertia. The power of the data—showing that only 54 percent of PPS high school students were graduating and that half of those dropping out could be identified well before they left 9th grade—was hard to deny. The Connected by 25 consortium was in the process of releasing the white paper on the dropout problem, and it had highlighted the importance of the 9th grade transition year. Consortium members were fully engaged with the issue, they were publicizing it throughout Portland, and they were eager to mobilize to support efforts to reduce the dropout rate. Finally, Phillips, Rennie-Hill, Smith, and their district leadership team colleagues were all determined to press ahead, the superintendent transition notwithstanding.

On the last day of May, exactly one week before high school graduation, OHS leaders and administrators gathered to review the available student data for the incoming 9th grade class and discuss their options. Of the two highest risk student segments they had identified—academic priority students and late entrants—one subgroup of students stuck out—those who were already flagged as academic priority students by their performance in middle school. About 70 percent of the academic priority students at high risk of dropping out were already sitting in 8th grade classrooms across the city, if they could only be identified. By acting now OHS leaders realized they could increase the chances of graduation for a large number of Portland students before they ever set foot in one of the district’s high schools. While the path forward was unclear, and while there would be challenges in crafting and implementing any major initiative, Rennie-Hill made her aspirations clear: OHS was not willing to postpone improving the chances for these students.

Learning About the At-Risk Students as Individuals

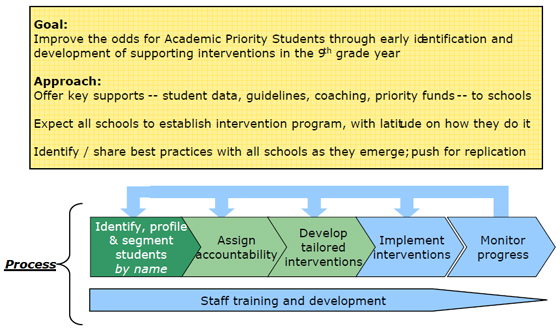

Rennie-Hill and her team needed to develop a plan of action. Given the compelling evidence, they determined that the district’s Academic Priority Initiative would aim to help at-risk students improve their academic trajectories, and prevent them from dropping out, through early identification of at-risk 8th graders and intervention focusing on their 9th grade transition. To make this initiative real in the absence of any demonstrated best practice, to drive it from the district to the schools in a traditionally decentralized environment, and to ensure school-level ownership during an extremely tight timeframe, the OHS team also decided that its approach had to be flexible. As a result, the team designed the implementation plan with emphasis on bottom-up creative problem solving at the school level rather than top-down edicts.

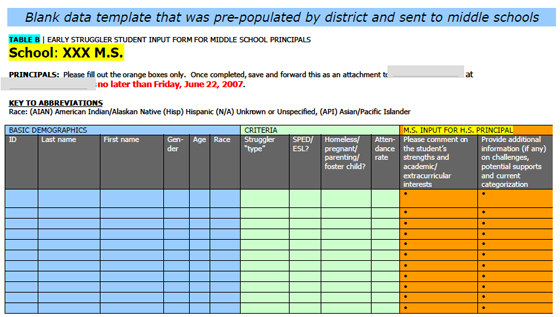

As a first step, the team joined forces with R&E to identify and profile at-risk 8th grade students by name. Importantly, OHS and R&E staff members were determined to use only easily trackable, well-defined indicators compatible with their existing data systems. They also relied exclusively on data that was already available in the central system (e.g. 7th grade test results) instead of waiting for the best-case data to be released in August (e.g. 8th grade test results).[11] Research and Evaluation Department staff took the lead in this work, which produced actionable lists of at-risk students containing their academic performance and conduct history, as well as information about whether or not they had faced certain “life challenges” (i.e., pregnant and parenting, homeless or foster status). The lists also contained supplementary demographic data. Armed with this information the team knew who the at-risk students were and which high schools they would enter in September.

The data was illuminating; however, it also presented the at-risk students as flat statistics. Moreover, high school administrators had indicated that if they received a document focused exclusively on a student’s challenges, they would be more likely to think of that student as a “problem” student. The Office of High Schools staff wanted to provide high school administrators and teachers with a basis on which to build a relationship when working with each student. To that end, OHS and R&E staff engaged with staff from the Office of Schools (OHS’ counterpart for grades K-8) and individual middle school administrators to solicit observations on the strengths and interests of each one of the students identified in the academic priority population.

While this attention to detail at the individual student level was consistent with the “every student by name” focus of the district, it also represented a first—nothing like this had ever been attempted in Portland before. In less than 10 days, though, much to the pleasant surprise of district leaders, every middle school had responded with detailed information on every single struggling student. The unprecedented district-wide collaboration to support these students through the 8th to 9th grade transition enabled OHS to provide lists with quantitative and qualitative data on every incoming at-risk student to high school administrators during the first weeks of summer.

School-Specific Interventions

Rennie-Hill and her OHS team received immediate and overwhelmingly positive feedback from high school administrators on this data. One commented: “This is one of the most useful reports that have been generated for me in the four years I have been a vice principal. Kudos for understanding how much data can drive decisions and supports.”

However, the team recognized that they needed to provide additional supports for administrators as well, to help them work with their own school teams to develop intervention plans for the academic priority students entering their schools. In that spirit they created a how-to guide that provided advice on developing systems of supports and accountability at the school level, offered on-going coaching (from both OHS and R&E), and committed to providing data reports every four to five weeks throughout the school year, tracking student progress. The Office of High Schools also marshaled approximately $1.25 million in one-time “priority” funds allocated by the Portland School Board to support the 9th grade initiative. An important focus of this funding was to support contracts to broaden the use of Open Meadow’s Step Up program at small school campuses and to support the work of Self Enhancement, Inc., another Portland-based nonprofit that focuses on helping African American students enrolled in PPS overcome barriers to their success.[12]

Over the course of the summer OHS also helped school administrators form their own small working teams, assign an adult to advocate on behalf of students (and be accountable for their support), and develop specific interventions that were to be implemented on or before the first day of school. Administrators had great latitude in crafting their particular initiatives with good reason: PPS encompasses a wide assortment of schools with diverse needs, populations, and sizes. As a result there was considerable variety in the approaches taken across the district. But there were some commonalities as well.

Interventions at the Larger Schools

At Portland’s comprehensive high schools, which each accommodate between 1,500 and 2,000 students, the most common intervention was sharpening the focus of 9th grade “academies” to support the at-risk students. An academy in the PPS system is a group of about 100 to 120 students who are assigned a team of core curriculum teachers. In some instances a counselor, special education and/or an ESL teacher provides additional support. One of the primary objectives of the academy approach is to personalize large, comprehensive schools and to facilitate strong relationships between teachers and students. During their common planning time, for example, academy teachers can have specific conversations about the students they interact with every day. The academic priority initiative motivated teachers and administrators to seek additional ways to learn more about students, and to keep a closer eye on their progress than they had previously. As one Portland administrator commented, “This initiative allowed me to see how I need to work with the counselor and the 9th grade team on a weekly basis to collaborate regarding the status of the 9th grade class.”

Other interventions included: providing students with mentors; increasing before- and after-school tutoring; double-blocking (designating two periods in a row) for core subjects like English and Math; increasing staff focus on attendance; and increasing the number of conferences held with the parents, the student, and all three academy teachers to discuss opportunities and challenges in real time. Teachers and administrators reported that these measures increased student feelings of connectedness, facilitated staff communication, and increased the level of specificity, and therefore productiveness, of parent-teacher conferences.

Preliminary student results varied across the comprehensive schools, with several making more significant gains in the first year. Among them was Cleveland High school, which provides a good example of an effective approach to implementation of the 9th grade transition initiative at a comprehensive high school. In the first year of the initiative Cleveland demonstrated a 25 percentage point reduction in number of students experiencing three or more core class failures—which, as we saw earlier—is a critical threshold to avoid in order to improve the odds that academic priority students will end up graduating from high school.

One working hypothesis for Cleveland’s success stems from the fact that it has some of the most well-developed 9th grade academies in the district. Whereas some comprehensive high schools were establishing academies for the first time in the fall of 2007, Cleveland’s academies were already in their sixth year. Many of the support structures for 9th graders and for their teachers (e.g. freshman orientation) were also already well established on the campus; thus the academic priority initiative was rolled out onto a solid foundation of existing supports. However, Cleveland also benefited because administrators articulated clear goals up front and aligned staff members around those goals before the school year began. Their goals were: Academic priority students would have at least six credits by the end of the year; attendance would increase; students would be connected with at least one significant adult in school; and there would be fewer behavioral issues.[11] To this end at-risk students were split up evenly between the 9th grade academies at Cleveland. Each was assigned an adult mentor and no one adult was responsible for more than five students. The approach each mentor took with their students varied. Some helped their students get modified assignments and differentiated instruction, some supported their students in accessing extra services (e.g. tutoring, freshman support class and social services), some communicated directly and frequently with parents, some provided incentives and support to students (e.g. taking them to concerts, out for pizza, or watching their “big game”). As Cleveland’s school administrator noted, looking back: “The focus on relationships was invaluable for these students… the fact that there was someone there helping them and holding them accountable.”

Staff collaboration was emphasized, as well. Counselors provided the next tier of support after teachers (e.g. referrals to a special course focused on improving study and learning skills). The athletics department also actively participated by agreeing that all 9th grade athletes had to attend all available tutoring if they wanted to play their chosen sports.

In addition Cleveland innovated by placing teachers who also taught honors and advanced placement courses in freshman academies, thereby exposing 9th graders to some of the most experienced teachers in the school. In the words of an administrator at Cleveland: “Putting these teachers in 9th grade is important because they set high expectations, and most kids strive for whatever bar you set for them. We have high expectations in 9th grade. Three quarters of the freshmen teachers also teach juniors and seniors so they understand what level it takes to graduate and go to college.”

Finally, Cleveland (like many other PPS schools), increased the frequency of student-parent-teacher conferences. The more-personalized academy structure, along with detailed data sheets provided by OHS and R&E, and the common planning time for academy teachers enabled these conversations to be grounded in and specific to individual student needs.

Interventions at Smaller Schools

Students at Portland’s smaller high schools typically have 300 to 400 students enrolled in all grades. In this environment the teachers and administrators can and do know most of the students in their schools by name, so many of the objectives of the “academy” design are already met, simply due to the schools’ structure and size. However, unlike most of the district’s comprehensive high schools, Portland’s small schools tend to be located in some of the poorest areas of the city and have a much higher preponderance of poor and minority students. On average small-school students also enter the 9th grade with a significantly lower level of academic preparedness. Due to these differences in the incoming student body, small-school staff tended to craft more systematic and sweeping intervention programs aimed at improving the experience of all 9th graders at their schools, rather than focusing specifically on pre-identified at-risk students.

Some common activities at small schools included: systematic efforts to provide flexible options for credit recovery; partnering with community-based organizations for intensive and tailored interventions; adjusting instructional practices; encouraging teachers to rely on data to make decisions; and increasing staff focus on attendance. Early results from small schools like BizTech (one of several schools in a complex known as the Marshall campus) show that through a sustained focus on changing what is happening in the classroom and on transforming instructional practice, it is possible to show substantial improvement even in the most challenged schools. BizTech demonstrated a 37 percentage point reduction in number of 9th grade students experiencing three or more core class failures.

In September of 2007 BizTech had a new administrator, Ed Bear, who was eager to engage with the academic priority initiative. His first step was to form professional learning communities (PLCs) for his 9th grade staff, designed to support teachers’ professional development by helping them hone their instructional practice as they reviewed emerging student data and results. “I did this because I believe in the power of PLCs to support instructional practice,” he explained. “The internal teaching practice is what really needs to be transformed.”

The staff alignment behind this strategy was a key to its success. Teachers were able to collaborate together on an ongoing basis about how to motivate and engage their students—and what new approaches to take if students didn’t learn a particular concept the first time around. One noted, “I have come to understand the vital necessity, impact and value of everyone working together as a team and towards a bigger goal.” This collaboration was also supported by BizTech’s grading system, which allows teachers and parents alike to see how each grade breaks down into specific proficiency criteria and enables teachers to be specific about what a student needed to demonstrate in order to move a grade from failing to passing.

Importantly, Bear also encouraged teachers to give students who were on track to fail courses “incompletes” at the quarter and semester marks, and to be very clear about the specific proficiencies the student needed to demonstrate in order to pass the class. “So many students have credit deficits. It is vital to prevent that and to help them recover,” he explained. “This year many of my teachers went above and beyond by giving incompletes at the semester and helping students at the margin get the credit.” Over the course of the year, BizTech also shifted tutoring to be focused specifically on credit recovery for students, which acted to reinforce the shifts in instructional practice in the classroom.

Cross-District Collaboration and Supportive New Leadership

While staff at both comprehensive and small high schools implemented their programs, OHS and R&E staff members were actively supporting the work by providing priority funds, significantly increasing the focus of data provided to schools, and coaching and training administrators.

They also enabled administrators to collaborate across the district (at the same time encouraging them to stay focused) by holding an ongoing series of “key results” meetings for them at the district office. Small groups of administrators met with OHS and R&E directors approximately eight times over the course of the year to discuss both the issues they were grappling with for the academic priority initiative in their schools, as well as how to access, understand and manage the student data at the district’s disposal. An added benefit: by completing some extra work, administrators were eligible to receive credit for their participation from Portland State University.

These meetings, and the support and focus they provided through implementation, were widely praised by administrators. One noted: “The work we were doing in key results forced us to be accountable for these students. And sometimes we need that. This gave me a little extra push to be responsible as an instructional leader.” Administrators also noted the importance of hearing what other schools were doing. “I really valued the key results meetings in general as a time to have a supportive conversation with my colleagues and find out what they were doing at their schools.”

Meanwhile, in October 2007, the long-term prospects for the initiative were given a considerable boost when Carole Smith was named the new superintendent of schools. Often, when leadership transitions occur at the superintendent level, it’s not uncommon to see nascent initiatives fall by the wayside as new leaders strive to set and implement their own agendas. In this case, however, that risk wasn’t an issue. Smith’s ongoing support of the initiative had already been made tangible, both through her actions and engagement with the project as Phillips’ chief of staff as well as through her prior work at Open Meadow and with the Connected by 25 coalition. On becoming superintendent Smith reaffirmed her commitment to the initiative by taking action to ensure that it became a part of the school district’s ongoing budget for 2008-09.

Progress Report—and a Look Ahead

As noted PPS has made visible progress in the first calendar year of the initiative. More than 65 percent of administrators agreed or strongly agreed that:

- the adults in their building are strongly committed to the academic priority initiative;

- that they had a systematic intervention plan for the academic priority initiative prior to the start of school (that first year); and

- that they had implemented that plan with fidelity.

Additionally, more than 80 percent of school administrators thought that the initiative had either a substantially positive or somewhat positive impact on the behavior of adults working with academic priority students at their schools. They reported that the initiative enabled adults to be more proactive by creating more personalized learning settings and awareness of specific academic issues. They also reported that the initiative had increased communication and collaboration among school staff, between high school and middle school staff, and between students, parents and teachers. Finally, they reported that the initiative better prepared staff to know and connect with all incoming 9th graders.

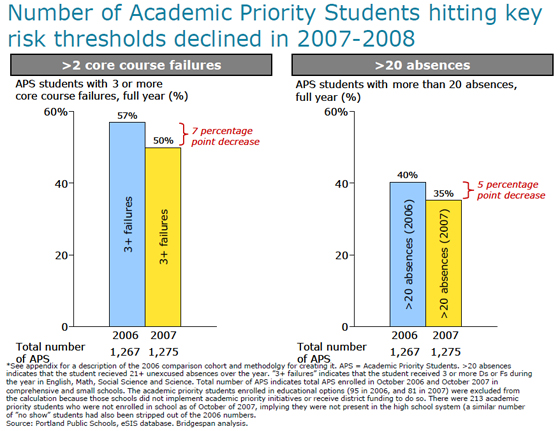

What’s more, counter to the expectation that student results would not change within one calendar year, there was also evidence that outcomes for academic priority students did improve on key dimensions, and not just at the most successful high schools profiled above. A comparison of the results of 9th grade academic priority students from 2007-2008 with the results of students who, using the same selection criteria, would have been designated as academic priority students in 2006-2007 (a year prior to the initiative’s launch) shows observable differences. In aggregate, as indicated in the exhibit below, there was a seven percentage point decrease in the number of academic priority students who received Ds or Fs in three or more core classes, which translated into keeping 90 students on the right side of this critical threshold, raising their projected chance of graduating from ~3 in 10 to ~7 in 10. There was also a five percentage point decrease in the number who received more than 20 absences, which translated into keeping 64 students on the right side of this critical threshold, raising their projected chance of graduating from ~2 in 10 to ~6 in 10.

These signs are encouraging. And although it is too early for conclusive results, some strong hypotheses have emerged from PPS’s first year of academic priority work that should guide the district’s actions going forward.

The first is that the highest performing schools provide examples that should be replicated in a more systematic way in the coming years. In the first year district leaders intentionally let many flowers bloom; at this stage it should start to identify those practices that appear to be driving differential results and use its funding, other incentives, and ongoing use of Key Results groups to encourage more widespread use of them.

Second, and not surprisingly, the most effective interventions appeared to be those that involved improved instruction, e.g. the assignment of experienced upper level teachers to 9th grade courses at Cleveland or the development of peer learning communities at BizTech. School programs that do not in some way improve what is going on in the classroom are not likely to move the needle over the long term.

Third, asset-based communication with students is much more effective than deficit-based communication. In the words of one academic priority student in a focus group: “It is so bad to be called a failure. It is like those cop shows where they keep telling you that you did it, and even if you didn’t sooner or later you say you did. At a certain point if you have been told you are a failure you start to believe it and it becomes true.” PPS instructional leaders and teachers should continue to develop instructional practices that focus on students’ strengths and hopes—and that move beyond the mistaken belief that assignment of a failing grade is a good way to motivate struggling students to do better.

Despite the progress that the academic priority initiative was able to make in one year, there are important ways in which it needs to be enhanced and developed further. The district’s R&E department also should continue its intensive and effective work with school administrators to understand and improve data systems. One of the most important data priorities moving forward should be devising a simple method to track which interventions each academic priority student receives, how long they receive those interventions for, and how student outcomes compare across different sets of interventions. It will also be important to complement the baseline information provided on incoming academic priority students with real time information that enables school teams to identify and initiate appropriate supports for students whose transitions risks and struggles do not present themselves until during their 9th grade year. It will also be important for school teams to find ways to continue to support academic priority students as they advance from 9th to 10th grade and are replaced by a new class of freshman. The challenges faced by the rising 10th graders, even if they were successfully addressed in the 9th grade, will not go away entirely, and in the case of many students continue to present major barriers to their chances for success.

Another risk to the full establishment of this initiative is potential fatigue among many school administrators, their staffs, and other stakeholders who thus far lack the definitive student results that might reinforce the effort at their schools. To mitigate this risk the district can clearly communicate that this is a three-to-five year transformation process and clarify for administrators which indicators really matter (e.g. the three or more core course failures and greater than 20 absences thresholds). Most important, the district can and should share the emerging positive results to date and hold up those school teams that have had the most impact as examples for their colleagues. While it is still too early to declare victory, it is now possible to celebrate the initial success stories.

At the close of this report it is important to take stock of the tremendous accomplishments made within the one calendar year of PPS’ 9th grade transition work. Historically siloed district offices consistently collaborated to bring simple, but nonetheless powerful, data to bear on the seemingly intractable problem of high school dropout rates. In an uncertain external environment of leadership transition they cut through bureaucracy and inertia, deciding to act against the status quo on behalf of Portland’s most vulnerable students. On a tight timeframe, middle school leaders collaborated to provide detailed information on each struggling student. High school administrators embraced the initiative, and used the data and other supports from the district to begin changing the behavior and beliefs of the adults in their buildings against the odds. Students’ performance on the critical dropout risk indicators improved in aggregate as more of them were supported in taking ownership of their learning and their futures. These accomplishments send an important message to students, to their parents and to the community at large. The launch of the 9th grade transition work in Portland shows us that an urban school district can take timely and effective action to address the dropout problem.

Take-Away Lessons for Other Districts

Several aspects of the district’s approach are worth calling out as lessons that could well be relevant for other districts seeking to launch ambitious change programs:

1. Act with urgency, even when it isn’t comfortable

Part of this approach involves zeroing in on the key facts, no matter how brutal, and using them to drive change. The key facts in this instance were first, that 46 percent of Portland Public Schools (PPS) high school students failed to graduate. This defined the status quo and how far short the district was falling of its ambitious goal to educate every student by name. The other key data point was that 47percent of the students who would dropout could be identified by their 9th grade year using a few basic and accessible indicators. This gave district leaders, school administrators and teams the knowledge and the confidence they needed to act. The Academic Priority Initiative was grounded on such powerful data that it was a force with which everyone had to reckon. The data ultimately wasn’t complicated. It contained a clear and self-evident urgency to act on its implications.

It would have been very easy in May of 2007 to wait—until the new Superintendent was on board, until the overall high school strategy was finished, until the right electronic data could be arrayed in the temporarily disabled state systems, until a better point in the (next) school year to allow more lead time, until all the measurement systems were in place, until…, etc. The fact is that there is never a great time to do something big and there can always be found a reason to delay. The spirit and urgency with which the Office of High Schools (OHS), the Office of Schools, the Research and Evaluation Department (R&E), the middle and high school administrators and their school teams rose to the occasion in June of 2007 and decided to plunge ahead, notwithstanding all of the reasons to wait, reflects precisely that commitment to action that should animate the work of all educators seeking to help disadvantaged children in our public schools.

2. Carry out initiatives in ways that make it easy for schools to change—otherwise they won’t

In order for any initiative to take hold and result in positive change for students, the concept and process must first be understood and embraced by administrators and faculty. The first step here is to clearly communicate in a sustained and actionable way the nature and importance of the initiative to the schools. As noted above, PPS is a district undergoing a wide array of district-led changes, all of which place demands on and require responses by school administrators and teachers. It is therefore important to communicate the relative priority of any one change at its launch and on an ongoing basis to keep the school teams focused appropriately. The 9th grade transition work was clearly a top priority for OHS— Leslie Rennie-Hill and her team communicated this on a consistent basis, beginning with the initiation of the effort in June, at the administrators meeting to kick off the school year in August, at the monthly administrators meetings throughout the year, and in the key results groups in which administrators regularly participated. The sustained elevation of this work as a priority thereby picked up a growing resonance with administrators, to the point where it came to shape even their vocabulary as they talked about how they were working with academic priority students.

It is always easier for schools leaders and staff to adopt district-led changes when they can build on work they are already doing. The OHS strategy of initially prescribing not the specifics of what schools should do and how they should do it but rather only that they needed to do something paid dividends in facilitating the adoption of this priority. It left the school teams free to incorporate and customize the 9th grade transition supports into the work that they were already doing, whether it was continuing to integrate and develop the freshman academies in the comprehensive schools, or articulating and fleshing out an integrated instructional model in the small schools. This strategy also reflected a humility that is often missing from district level changes in that it left the initiative at the school level, where it ultimately needs to reside.

Finally, the district led with supports instead of challenges. The Office of High School’s strong initial focus on supporting schools in this work—in the form of highly valued and practical student-level data, coaching and guidance on how to get started, and academic priority funding for compelling proposals—effectively served to grease the skids, encouraging and enabling effective action by the schools instead of demanding performance without necessarily providing the means to perform. It was particularly important here to provide differentiated levels of support for those small schools that faced the biggest challenges based on the preponderance of academic priority students in their incoming 9th grade cohorts. To be sure, supports from the district for the schools will increasingly need to be buttressed by challenges to the schools in order to get to the desired outcomes for academic priority students. Now that the schools have made some headway with the support of the district, the district is in a better position to begin challenging as well as supporting them to deliver in this regard.

3. Make data driven decisions

Regardless of the actions implemented at the school level, there was broad consensus among administrators that the data and the focus it provided was the most valuable component of the academic priority initiative. An administrator noted, “What was so powerful about this process is that we were truly able to base decisions off of deeper evidence and not just what we saw on the surface.”

Indeed, the data brought to bear—the student-by-student lists provided before school as well as the progress tracking reports R&E sent to administrators every 4.5 weeks throughout the year—represented a new commitment in Portland to use targeted information to support schools to act. Administrators were trained to manage with that data through regular coaching from R&E, OHS and their peers. The following comment represents this broader sentiment: “Through our work, we have built a dynamic of shared leadership and are accepting ownership for our results. The specificity of this data analysis demands and makes it safer to take full ownership of ALL our students.” Another explains, “This data study has helped me own our results and inform our planning decisions for next year. Now I will always remember that each set of numbers is a child with a bright future.”

Looking back on the year the majority of high school administrators strongly agreed that the early identification was the most helpful support OHS provided. A response on a year-end survey of administrators indicated that, “Generating the summary list and sending it prior to the start of school caused the cascade of other positive effects.”

4. Focus on fostering great teaching and learning—for every student by name

Ultimately what matters is what happens in the classroom. This initiative was based on the premise that what was most important was the quality of teaching and learning in the classroom--where teaching and learning was rich and robust, academic priority students would flourish; where it was not, the academic priority students would struggle, no matter how extensive the network of external supports. It is no accident that the schools who showed the most progress in the first year were ones where the efforts to improve the quality of instruction and the efforts to support academic priority students were one in the same.

There was also incredible power to the individual student level information that was developed by the middle schools, cross-walked by the OHS and R&E teams, and then utilized by high school administrators and their staffs to understand the (different) strengths and challenges that their incoming academic priority students faced. Likewise there was power in assigning accountability for each student’s success to an adult at their high school. To be sure, while the power of this accountability and the relationship needs to be more fully tapped (the impressions after the first year were that performance varied across and within schools depending on the commitment of the adults involved), the academic priority students would never get the level of support they need without it.

5. Involve the community

The PPS initiative was grounded in the greater Portland community, as evidenced by the district’s collaboration with The Connected by 25 consortium. The importance of this “outside” link shouldn’t be overlooked. Outside connections, support from community groups, and the expectations that are communicated from these outside entities all help an initiative gain momentum. They also can provide significant continuity if and when changes within a school system (e.g. leadership transitions or budget crises) threaten an initiative’s focus or its future. The PPS initiative to help transitioning 9th graders ended up being bigger than the district. And that broader support was an important buttress, which helped keep the community and the district focused on the dropout problem from one superintendent to the next. The consortium thus helped create an environment that both supported and expected improvement.

[1] Bridgeland, John, John DiIulio, and Karen Burke Mason. “The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Drop- outs.” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: March 2006. Data referenced is from Greene, Jay and Marcus Winters (2005). Public High School Graduation and College-Readiness Rates: 1991–2002. Education Working Paper No. 8. New York: Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

[2] Alliance for Excellent Education. (2007, September). FactSheet: High School Dropouts in America. Washington, DC.

[3] Alliance for Excellent Education. (2003, November). FactSheet: The Impact of Education on: Health & Well-being. Washington, DC.

[4] Learn more about Connected by 25’s mission and initiatives.

[5] Oregon Department of Education website.

[6] Cohort definition: Students enrolled as 8th graders in final quarter of 1999-2000 school year; Students who entered PPS from outside the district as first time 9th, 10th, 11th or 12th graders in subsequent school years (2000-01, 2001-02, 2002-03, 2003-04); No older than 17 yrs. in 1999; Enrolled for at least one full quarter from the end of the 8th grade to the end of the 12th grade. For the full report, see Mary Beth Celio and Lois Leveen, “The Fourth R: New Research Shows Which Academic Indicators are the Best Predictors of High School Graduation—and What Interventions Can Help More Kids Graduate,” Spring 2007.

[7] 34 percent entered 9th grade underperforming; 36 percent failed a core course in 9th grade; 46 percent were behind in credits after 11th grade; 14 percent entered late or dropped out and re-enrolled; 15 percent were missing key data ; Only 1 percent were not explained by any indicator.

[8] Core courses include English, Math, Social Science and Science. For the purpose of this analysis, receiving a D or an F is considered a failure.

[9] “Connecting entrance and departure: The transition to ninth grade and high school dropout.”: Education and Urban Society, July 2008; 40: 543 - 569. For additional research on the importance of the 9th grade transition see (1) Black, Susan. “The Pivotal Year”, American School Board Journal, February 2004: Vol. 191, No. 02. (2) Allensworth, Elaine and John Easton. “What Matters for Staying On-Track and Graduating in Chicago Public High Schools: A Close Look at Course Grades, Failure, and Attendance in the Freshman Year.” University of Chicago, Consortium on Chicago School Research: July 2007.

[10] Receiving a D or an F in a core course is considered a failure for the purposes of this analysis.

[11] Due to a technical glitch state assessments for 8th graders wouldn’t be available until late August, much too late to give administrators the full benefit of early identification.

[12] See more on Open Meadow’s Step Up program. See more on Self Enhancement Inc.’s program. See also Daniel Stid and Regina Maruca case study, “Self Enhancement, Inc: From the Pristine World of Strategy to the Messy World of Implementation,” October 2008.

[13] Twenty-four credits are currently required for graduation in Portland (classes of 2009 and 2010). However, the class of 2011 will need 25 credits.