This article was updated on February 9, 2023.

Over nearly five decades, Population Services International (PSI) has established itself as an international leader in delivering affordable health products and services in over 50 developing countries. Recently, it has taken on an added mission aimed at promoting systemic changes to make healthcare broadly available and affordable. That’s the goal of a growing global movement in support of health coverage as a fundamental human right—a movement that PSI wants not just to join, but help to lead.

To chart its bold expanded mission, PSI initiated a strategy review to identify how it could promote changes in public policy and health funding, shape healthcare markets, and attract funding from global philanthropy in support of consumer-powered healthcare. This new direction, however, raised a number of daunting questions. Among them: How would its Washington, DC-based headquarters work with regional and country teams to deliver these new activities? How could PSI harness rapid learning across global projects and markets? Who would decide which policy changes and projects to pursue in each market? What new capabilities would PSI need to ensure success, and where should those capabilities reside within the organization?

Such questions highlighted the need for PSI to examine how its expanded strategy would require changes to how it works. “For an organization that prided itself on delivering solutions directly into the hands of consumers, the commitment to systems solutions to ensure sustained access to basic healthcare presented a challenge,” says Michael Holscher, PSI’s chief strategy and resources officer. “It was clear from the CEO level down that unless we reorganized in support of our new strategy, we just couldn’t succeed.” In short, PSI needed to retool its operating model, the blueprint for how to organize and deploy people and resources to translate strategy into results.

For PSI, the new strategy required a number of operating model adjustments, including clearly articulating an accountability framework to coordinate roles played by different types of teams across the organization, adopting behaviors that promote greater collaboration, streamlining decision processes, and in some selected areas, altering organization structure. The long-standing practice of grouping countries by geographic region was changed to grouping by three market types: “foundation” markets in early stages of quality health delivery; “transition” markets working to scale quality delivery; and “acceleration” markets focused on transforming healthcare care systems. This new approach allowed PSI to focus on the specific needs of each segment, differentiating resources, accountabilities, and decision roles across headquarters, regions, and country offices. As PSI has moved forward with this market restructuring, additional benefits have continued to emerge. For instance, PSI has been able to craft more targeted fundraising appeals, for, say, ramping up early-stage markets or underwriting advocacy for health policy transformation. “These changes are the gift that keeps on giving,” says Karl Hofmann, PSI’s CEO.

Nonprofit Resources

📄 Get more of our best articles, tools, and templates on running a thriving nonprofit.

Explore NowThe benefits from investing in operating model upgrades are well established in the business world. Bain & Company’s research spanning eight industries and 21 countries, for example, has shown that redesigning an outdated operating model to align with evolving strategies may be one of the smartest investments a company can make. Bain found that companies rated in the top-quartile of operating model performance have five-year revenue growth and operating margins significantly higher than for those in the bottom quartile.1

Nonprofits stand to gain similar benefits in productivity and impact, as we have found from our experience adapting Bain’s operating model framework to the social sector. Yet, in our work with hundreds of nonprofits, we have found that most don’t pay enough attention to their operating models. For example, in a recent Bridgespan survey of 25 national nonprofit networks—large direct-service organizations with many branches or affiliates—almost 80 percent of respondents said that their organizations spend enough time and resources working on strategy, while only about 50 percent said the same about their operating models. Many nonprofits proceed from defining their strategy to laying out implementation plans without taking a step back to consider whether their organizational setup stands in the way of success.

What is a nonprofit operating model?

Every nonprofit has an operating model, even if it is not named as such. It describes where and how critical work gets done to achieve an organization’s goals. For many nonprofits, operating models evolve by default over time rather than through explicit discussion and choices. Top performing nonprofits, however, make intentional choices about their operating models to ensure they act as a bridge between strategy and execution. Building this bridge well requires tailoring the operating model to support the organization’s “must-get- right” decisions and capabilities—those that are necessary for the strategy to succeed.

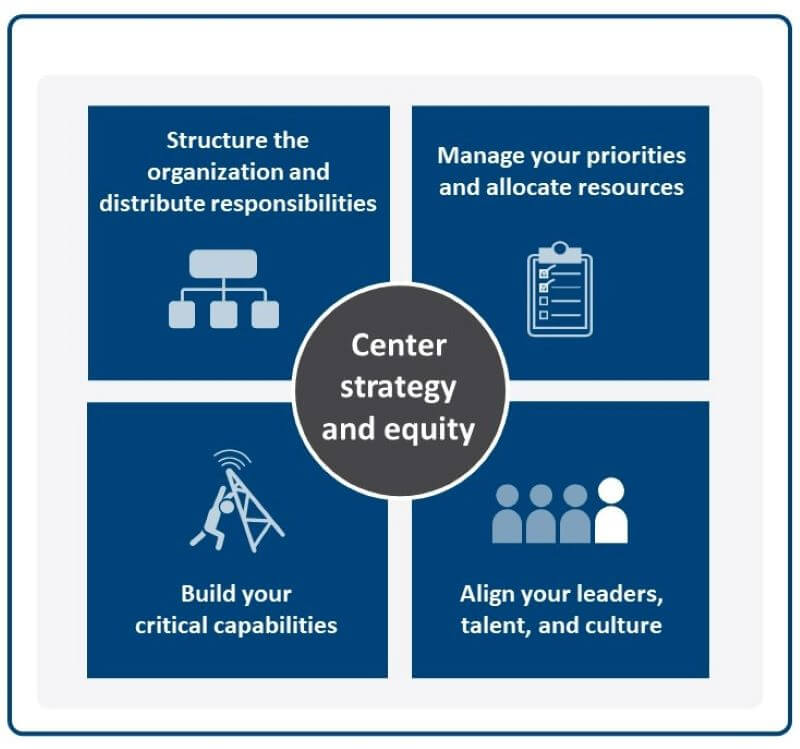

Bridgespan’s operating model framework guides the design of four interrelated elements (see chart below):

- Structuring the organization and distributing accountabilities clarifies where key work is done and who does it. Structure identifies key operational units, typically reflected in an organization chart, as well as the cross-cutting services and coordinating mechanisms that allow for collaboration and expertise sharing across them. Accountabilities specify roles and responsibilities, and clarify decision rights for issues that cross units.

- Approaches to managing your priorities and allocating resources are the ways the organization prioritizes, guides, and monitors its work. These include the executive forums, managerial processes, and metrics that support high-quality decision making on strategic priorities, resource allocation, talent deployment, and performance management. This operating model element also extends to board-related considerations, such as its composition, governance practices, and interactions with the nonprofit’s leaders.

- Aligning your leaders, talent, and culture captures how leaders guide their teams, and how colleagues behave and interact with one another. These are the cultural norms that go beyond broad values, such as trust and respect, to get explicit about how teams will collaborate across functions or geographies and where they will adopt innovative working practices such as Agile.2 Establishing the organization’s dominant decision-making style—whether consensus, democratic, directive, or participative—sets an important context for behaviors.3 Many organizations find that their key challenges have more to do with the way people work together—or fail to do so—than with structures or management systems.

- Building your critical capabilities optimizes performance across the other priority elements of the operating model. They include recruiting and talent development, data and technology, expertise in critical areas, learning and innovation, and supports to ensure that critical partnerships with other organizations are successful.

And throughout, your operating model should be designed with equity priorities and your strategy for impact at the center. The right operating model will help you achieve both, more effectively.

All operating models take shape around this framework, but each model is different. That’s because no two organizations—even if they seek to address similar issues— have the same approach to impact, funding model, strategic priorities, equity considerations, geographic scope, or cultural and leadership profiles. This means that organizations require tailored operating model choices to unlock impact.

In our advisory work, we observe that many nonprofits have spent a lot of time and effort working to improve various pieces of their operating models, such as leadership, talent development, decision processes, and operational capabilities. For the most part, however, leaders address these issues piecemeal without fully anticipating how a change in one area may impact another, or that more comprehensive adjustments might be needed. “The value of using an operating model approach is that it helps us understand that for every action we take in one area of our model, there are impacts and trade-offs on the other aspects of the model,” says PSI’s Holscher. For example, setting up a new unit, like an innovation hub, may have ripple effects on decision making, resource allocation, and the measures used to hold leaders accountable. The ultimate goal is to get all the model’s elements working in sync toward implementing the organization’s strategic plan—something less likely to happen with the piecemeal approach. Not surprisingly, when elements of a nonprofit’s operating model are out of sync, execution slips and impact suffers.

Tips for successful operating model redesign

Given the newness of the operating model concept in the nonprofit arena, many leaders will have questions about how to design or revise a model to achieve better results. In our advisory role, we have helped a number of nonprofits grapple with these questions. In addition to PSI, for example, we have worked with Project ECHO, a New Mexico-based telementoring organization that trains physicians in more than 35 countries, and the Ounce of Prevention Fund (the Ounce), a national nonprofit that supports early childhood development through research, advocacy, professional development, and direct services. From these and other engagements, we have identified eight best practices for tailoring an operating model to fit a nonprofit’s strategy, whether a full overhaul or a partial realignment.

1. Start with strategic clarity.

It is impossible to improve performance without strategic clarity. Redesigning an operating model begins here. Achieving clarity often requires a concentrated effort to answer a number of questions: What lines of business will the organization engage in—for example, direct service, advocacy, field-building, or a combination? What programs and activities will the organization pursue, and what does success look like in each? Where geographically will it operate? Approximately what scale is anticipated in the next three to five years? What funding model will support such activities? What capabilities will be required, and will the organization develop those capabilities internally or access them through partnerships? What are the critical decisions that our organization will repeatedly need to make quickly and well? What are our equity priorities, both in our strategy for impact and for how we operate as an organization? Nonprofit leaders need to get to this level of clarity to evaluate various operating model choices; for example, determining whether to organize structure and accountabilities around lines of business, or perhaps programs, geography, or function.

For Project ECHO, that strategic clarity started with a strategy review in 2017 that led to declaring the ambitious goal of reaching one billion patients globally by 2025. The new strategy required Project ECHO’s leaders to retool the organization’s operating model to meet the attendant execution challenges around decentralized decision making and massive scaling. On the ground, that meant empowering a wide range of global actors— primarily universities, NGOs, and doctors—to adopt the Project ECHO medical teaching model. The new operating model created a network of branch offices and regional super hubs, adjusting decision roles and processes to facilitate clear decision making across all the stakeholders.

The Ounce, in existence since 1982, initiated its 2013 strategic plan with a renewed focus on expanding the organization’s efforts to develop well-functioning early childhood interventions at scale at the local and national levels. This included an organizational emphasis on scalable knowledge-transfer and increased collaboration and partnerships among fellow experts and practitioners in the early childhood education field across the country.

This shift included a significant investment in R&D to translate a growing body of scientific evidence about early brain development and the organization’s program implementation and policy expertise into new, scalable early childhood solutions. Its operating model adjustments focused on ensuring that these new capabilities to develop and scale early childhood education and interventions were well-resourced and had the accountabilities and decision rights needed to thrive.

Even organizations that recently have engaged in strategic planning commonly find the need for further strategy refinements to get sufficient specificity on what work the operating model needs to support. For example, PSI had previously invested in a strategic planning effort in which the organization examined external trends and internal abilities, and identified a future role as a health market transformer. And yet, before the operating model design work commenced, PSI had to further engage groups across the global organization on what the new strategy would mean in practice on the ground. This frontline operational perspective helped to translate high-level strategy into the day-to-day reality of what an operating model must accomplish.

2. Use design parameters to define what matters most.

Once you are clear about strategy, you are ready to translate that strategy into a list of requirements for operating model design. We call these “design parameters”—a set of 10–15 written statements that describe what the operating model needs to do to enable the strategy. They may also highlight specific organizational challenges to address or strengths to preserve. These parameters essentially serve as criteria for evaluating operating model design alternatives. When a leadership team aligns around the design parameters before moving onto the specifics of operating model design, we find that difficult choices becomes easier as the parameters bring some objectivity into the process.

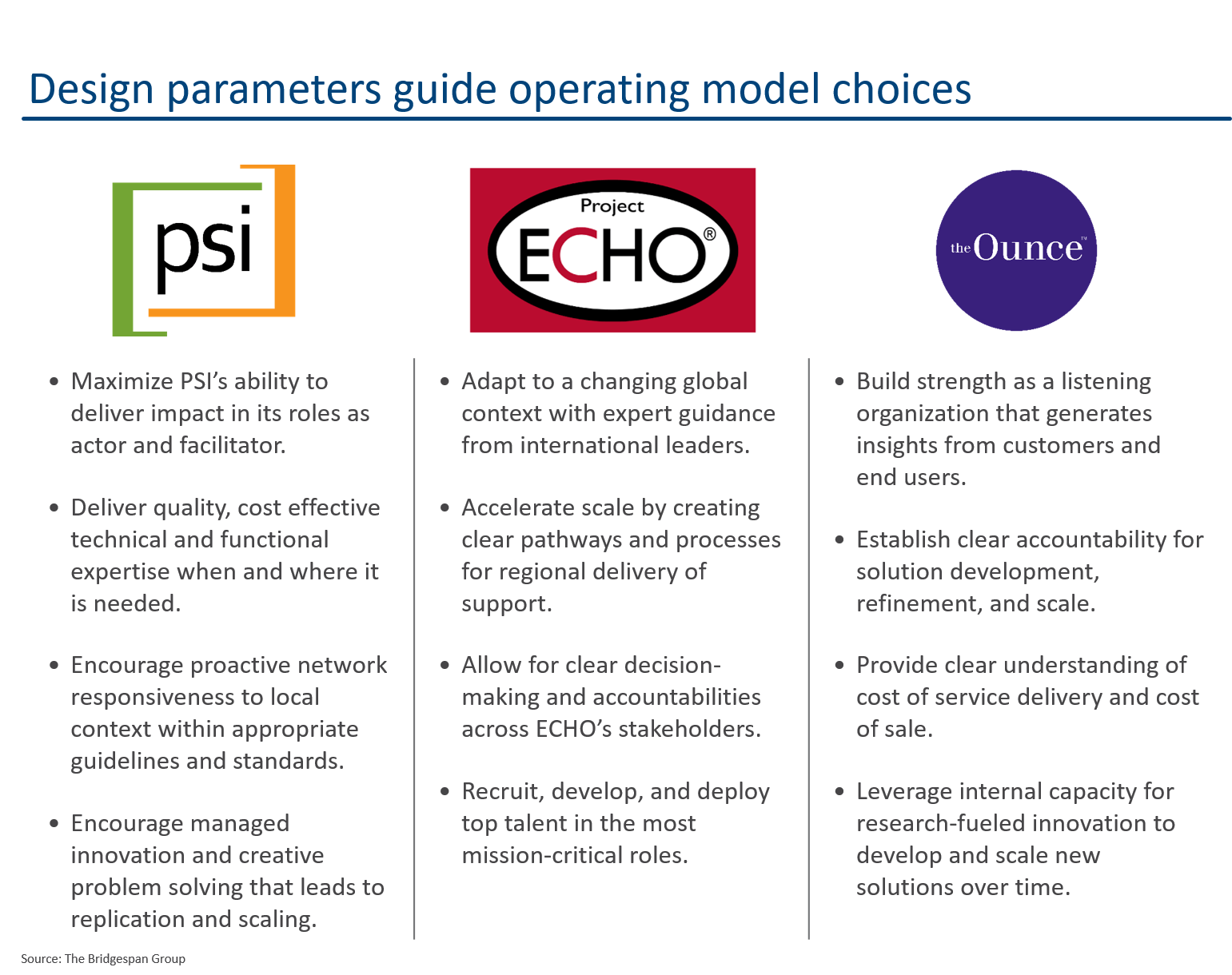

PSI, Project ECHO, and the Ounce each used design parameters as an objective assessment tool to consider various operating model choices and to identify which best satisfied their strategic needs (see chart below, “Design Parameters”). PSI developed its design parameters by consulting leaders across the organization. “Landing on design parameters was very unifying for the organization, both from the senior leadership perspective and the network members’ perspective,” says Ellen Tipper, PSI’s senior advisor for strategy. Then, PSI formulated six possible high-level structural options for consideration and evaluated each against its 10 design parameters. The project team converged around three leading options that met most parameters, then developed a best-fit hybrid model from among elements of the three.

For Project ECHO, a key design parameter aimed to accelerate scale “by creating clear pathways and processes for regional delivery of support.” With that goal in mind, the team sought operating model options that decentralized decision-making authority wherever possible and built capacity regionally versus centrally. The Ounce chose a design parameter to provide “clear accountability for product/solution development, refinement, and scale.” Following through led to the development of a new internal unit that “owned” product development. Another parameter—“leverages internal capacity for research-fueled innovation”—ensured that members of the new product development team would tap the deep expertise of colleagues outside the new unit.

3. Up your game on decision effectiveness.

An organization’s ability to execute well rests on its ability to make and implement the decisions that matter most. Many nonprofits struggle with timeliness and clarity of decision making, hampered by a broad range of factors: unclear priorities, consensus decision making, ambiguous decision roles, poor decision and meeting disciplines, siloed behaviors, or organizational structures that thwart collaboration and accountability. Even those nonprofits that have historically excelled at decision making can find that a strategy shift may necessitate additional supports and new decision-making approaches as they expand their reach and objectives.

PSI’s initial diagnostic identified decision effectiveness as a core issue to address in its operating model refresh. Ill-defined roles and processes meant that often meetings would end up with no decisions or the loudest voice would decide. Leaders realized that the new strategy would exacerbate these challenges and seized on the opportunity to build new decision-making capabilities. This meant streamlining decision-making processes, embracing the systematic use of the RAPID® decision-rights tool to clarify decision roles and engaging leadership across the organization in promoting behaviors consistent with these efforts.4 PSI focused initially on some high priority decisions, such as those cutting across the new market groupings, country offices, and the headquarters staff in Washington, with the intent to embed the approach more broadly.

At Project ECHO, the imperative to scale efficiently called for decentralizing decision making from the home office to partners operating in dozens of countries. Establishing the principles and guidelines for distributed decision making became an important part of the new operating model. “All the decisions about the diseases they work on and how they do it are up to them [partners],” explains founder and CEO, Dr. Sanjeev Arora. “As long as they do it with fidelity to our model, they can do whatever they want.”

For the Ounce, increasing the focus on knowledge sharing, solutions implementation, and scale required improving and streamlining decision-making efforts. Leaders recognized that decision effectiveness would be critical to repeatedly pilot, evaluate, and launch programmatic innovations that deliver value to customers. “We had a highly collaborative decision-making process,” says Ann Kirwan, vice president of strategy and partnerships. A focus on improving decision clarity, quality, and speed “led us to create a whole new division, hire a new leader, and bring all the pieces together,” she continued. The Ounce also adopted the RAPID decision framework to clarify who makes the call in different situations. “RAPID helped us streamline things,” Kirwan added.

4. Prioritize must-deliver capabilities over those that can be “good enough.”

Nonprofits typically operate in an environment of resource scarcity, which puts pressure on leaders to make tough choices about how best to spend available dollars. In such an environment, it’s important to prioritize those few capabilities most essential to delivering your strategic goals. In operating model design, naming these capabilities helps you make operating model design choices that make it as easy as possible to develop and deliver these critical capabilities.

The Ounce identified several critical capabilities it needed to achieve the nationwide impact to which it aspired. Among them: customer and market analysis, business development, and user-driven design improvement. Prioritizing these capabilities prompted a number of changes in the Ounce’s operating model, including setting up the aforementioned “solutions unit” to focus on innovative initiatives and adding staff with experience in marketing and sales.

For Project ECHO, accelerating global growth means investing in best-in-class staff expertise and connective technologies to deliver training and telemedicine across Project ECHO’s global platform. This required adjustments in organizational structure and staff compensation to position Project ECHO to attract this top-caliber talent. For PSI, the adjustment to group like markets together was an operating model design choice aimed in part at making it easier for PSI to concentrate and target its technical capabilities in the right locations.

5. Look past structure.

Organizational chart reshuffling is a go-to fix for many organizations trying to do something new or solve for underperformance. While structure is an important part of an operating model, it alone rarely holds the key for delivering on an organization’s strategy. “Do not confuse operating model redesign with a simple org chart exercise,” PSI’s CEO Hofmann explains. “It’s not that. That would be a pale version of operating model work.”

To be clear, structure matters. Our research finds a clear bump in overall effectiveness for organizations with supportive structures. But the bump is not nearly as large as the effectiveness gained by adjustments to other operating model elements, such as management and leadership behaviors. “You think you’ll solve the problem with structure, but in fact, it is a decision-making problem and accountabilities problem that you just haven’t clarified,” says Tipper, PSI’s strategy advisor.

6. Look both within and outside for inspiration.

Nobody knows the strengths and weaknesses of an organization’s operating model as well as its employees. Capturing and synthesizing that knowledge can provide a meaningful base for operating model design. PSI recognized this early on and elected to interview more than 40 executives, review previous internal analyses, and survey 140 leaders using Bridgespan’s operating model readiness survey. Not all organizations choose to deploy a survey of that magnitude, but any synthesis and assessment of internal perspectives can be useful in pinpointing important issues and building a strong case for change. When doing so, it is important not only to conduct management interviews with the top team, but also to intentionally name blind spots and explicitly seek input from perspectives underrepresented in senior leadership—consider dimensions such as race, gender, age, geography, function, and tenure.

External benchmarks also can be helpful. While each organization’s strategy and operating model is unique, leaders can learn from ways in which particular aspects of analogous organizations’ operating models are designed. The Ounce, for example, looked at peers in early childhood services to inform the critical capabilities it prioritized. PSI took inspiration from structural models used by for-profits to launch and scale new operations. “Ideas and perspectives that had nothing to do with PSI really helped to move our thinking,” says Holscher. Project ECHO drew scaling lessons from McDonald’s and Coca-Cola in planning for an operating model that could scale to impact one billion people by 2025.

7. Work with a small group before going organization-wide.

Operating model assessment and design can be a complex process. It can entail substantial change that may challenge an organization to embrace new roles, learn new processes, or act differently. To manage this process, start with a small group of leaders—the executive team or a core working team that brings firm-wide perspective—that can safely learn, debate, and experiment. The team can identify and codify the design parameters most essential to the organization. It can assess critical capabilities needed or explore barriers to effective decision making. This team also can seek guidance from frontline staff, key funders, and partners on particular issues. It’s also important to establish upfront a clear decision-making process relating to the operating model design itself. For example, PSI determined that the core working team would develop and debate recommendations, with the CEO making final calls.

Once the core team has designed a high-level blueprint, a broader group of management can be engaged in adding details to aspects of the model relevant to their work, thus encouraging ownership while also ensuring that distributed design work adheres to the high-level model.

8. Actively manage the long tail of the change.

Some aspects of an operating model blueprint can be implemented right away. Others, such as new processes or new roles, may require additional design detail before the model can be fully launched and work as intended. Oftentimes, this detailed design work can be distributed among leaders or teams located closest to where the change is needed, while working within the high-level blueprint defined by top management. Such complex change requires a well-managed approach that sequences modifications, distributes timely internal communications to keep everyone up-to-date, and provides reinforcement for trickier parts of the change process. Moreover, operating model behavior changes can take time to embed and need sustained leadership commitment to take root.

Is it time to consider an operating model update?

Sometimes the need for an operating model update is triggered by an evolution in strategy. PSI extended its strategy to include advocacy and systems coordination to its ongoing delivery of affordable health products and services to the poor. Project ECHO embarked on a massive global scaling effort. The Ounce chose to extend its impact on early childhood development by partnering with systems and networks of programs to implement its solutions. Such strategy pivots tend to strain an organization’s current operating model and demand new capabilities and ways of working. For that reason, PSI and Project ECHO explicitly paired their strategic planning efforts with focused attention on updating their operating models. At the Ounce, leaders experimented for several years with implementing their expanded strategic vision, which helped to clarify where to make targeted adjustments in their operating model to streamline product development and sales.

At other times, the case for revising an operating model may be less obvious. In our experience, a number of common challenges can serve as leading indicators for a redesign. We frequently hear nonprofit leaders frustrated with various organizational dysfunctions: resources spread across too many priorities, slow decision making, too much time spent in meetings, or difficulty attracting and energizing needed talent. Perhaps a new leader or new funder has raised the bar for performance, which exposes some internal weaknesses. Other nonprofits might realize they have outgrown an earlystage model and can no longer rely on founder-led decision making or ad hoc processes and systems. If any of these sound familiar, it could be time to revisit your operating model to ensure it provides a bridge from strategic ambition to quality execution.

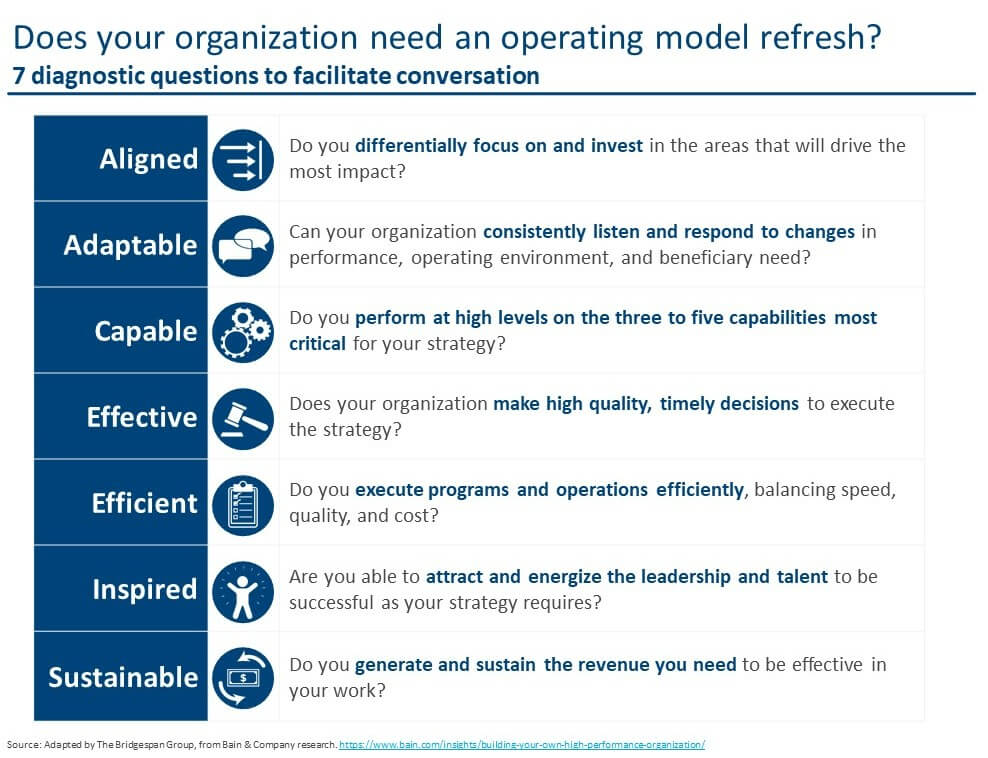

Whatever the trigger, start with frank conversations to explore how well the organization’s current operating model is working. Use the diagnostic questions in the chart below to facilitate the initial discussion.[5] Answering such questions can help you determine whether your operating model aligns with your strategic goals. If significant issues surface, the time may be right for an operating model refresh.

If the initial conversations uncover the need for operating model adjustments, take the next step, as PSI did, and use a comprehensive diagnostic to pinpoint priorities and build the case for change. Today, PSI continues to implement its new operating model, building momentum and buy-in within the organization and among its funders. “It’s clear that neither our strategic shift nor this new operating model will be easy,” says Holscher. “There’s a lot of work to do.” If the stakes are high, so is the potential payoff. “If we get it right,” he added, “this work has the potential to be profound.”

The authors thank Bridgespan Partners Gail Perreault and Jari Tuomala, Case Team Leader Nathan Aleman, and Editorial Director Roger Thompson for their contributions to this article.