Introduction

Related Content

Guide: Community Collaborative Life Stages

Leaders of collaboratives shared during a meeting in 2011 that community participation is critical even in collaborations led by civic, nonprofit, philanthropic and other senior leadership in communities.1 Without community members actively sharing in the process, collaboratives lose an opportunity for better results. As one sector leader puts it: “Without true community ownership, collective impact efforts will not be sustainable and lasting.” Beneficiaries give the work its context. Their involvement accelerates the desired change. And their ultimate buy-in helps to embed that change into the fabric of the community for future generations.

Many collaborative leaders readily acknowledge that a strong community partnership is needed to thrive, and yet most believe they have much to learn about ways to engage the community. Because their engagement and feedback is so crucial to success, we have prepared this guide to help collaboratives engage with individual community members. This guide was prepared as a part of the work Bridgespan completed to support the White House Council for Community Solutions. Community voice and community participation are areas of active inquiry and innovation in the social sector. This guide is intended to highlight some of the approaches of existing collaboratives and some examples of next generation approaches that focus on community participation. This is a guide for collaboratives that say “yes” to the following questions:

- Do we aim to effect "needle-moving" change (i.e., 10 percent or more) on a community-wide metric?

- Do we believe that a long-term investment (i.e., three to five-plus years) by stakeholders is necessary to achieve success?

- Do we believe that cross-sector engagement is essential for community-wide change?

- Are we committed to using measurable data to set the agenda and improve over time?

- Are we committed to having community members as partners and producers of impact?

This guide is also supported by two other documents:

- Community Collaborative Life Stages: This guide describes the five stages of a collaborative’s life, including case studies, a checklist of key activities, and common roadblocks for each stage.

- Capacity and Structure: The process of organizing a collaborative is discussed in this guide; it can help you answer questions such as what dedicated staff is necessary and what structure should support the collaborative.

We have divided this guide into five sections:

- Overview: We make the brief case for why community involvement is critical in tackling complex social problems, which by definition, do not come with set solutions.

- Examples of Community Collaborative Engagement: Successful collaboratives figure out ways to tap into the energies of their communities. Here is how a few have done it.

- Next Generation Community Partnership: New ideas are constantly emerging to solve old problems. For example, if you want to help youth, why not partner with those youth and have them lead the collaborative?

- Key Questions to Ask: From the collective experience of successful collaboratives, these queries can help shape your approach.

- Resources: Here we share the combined best practices and lessons from many outstanding collaboratives and their partners.

Overview

Technical problems, such as where to put a school, do not require the formation of collaboratives. Based on population or geography criteria, there is usually only one good answer. Collaboratives, however, are needed to address the proverbial "can of worms." Such "adaptive" problems are complex, multi-issue challenges that cannot be easily fixed with known or quickly discoverable solutions. Rather, what is needed is a process of discovery involving a diverse set of stakeholders.Community participation is critical to ensure that the interlinked efforts of many partners both reflect the context of the community and genuinely meet its needs, all of which sounds complicated, because it is. But the community level is the starting point. It is where the raw data can be found. It is also a source for thoughtful responses and effective solutions.

Poverty and poor student achievement are prime examples of adaptive problems. Engaging deeply with community residents on such thorny matters helps collaboratives clearly identify the pivotal issues and generate the needed trust to get people to attempt the change and to develop solutions. (Please see the resource Keystone Constituent Mapping.)

Challenges to full community participation

Most collaboratives start out by bringing the top community leaders together to work towards achieving community-wide change. The key question, though, is: Are all the right people on the bus? Historical community divisions and power imbalances often mean that collaborative participants do not represent the true diversity of the community. Likewise, beneficiaries also may not have a place at the decision-making table. Leaders of collective impact struggle to decide how and when to engage beneficiaries and grass roots leaders. When do you involve the community? How do you engage the community in ways that accelerate and sustain collective impact?

Funding is often another roadblock to generating true community involvement and representation. In a pay-for-performance atmosphere, providers might hesitate to report negative community feedback on their programs out of fear that it might draw attention to failure and cause dollar commitments to dry up (please see the resource Keystone Prospectus). Funders reinforce this through grant requirements linked to success metrics and an absence of specific funding for community feedback. (Please see the resources 21st Century Constituency Voice and Models of Community Engagement.)

Given these challenges, many collaboratives will readily admit that they are still struggling to fully engage their communities. But they also are persisting by exploring and testing new ideas. Obviously, there is no one formula for excellent community participation. That, too, is an adaptive problem. But some successful collaboratives have used approaches that are worth highlighting.

Examples of Community Collaborative Engagement

Simply put, community engagement increases the likelihood that interventions will be aimed in the right direction. Tried and true vehicles for engagement include community meetings, focus groups, surveys, and interviews. But sometimes it takes a large, coordinated effort.Community meetings to gather resident perspectives

For example, when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, the city desperately needed to rebuild its infrastructure and morale. But many people on the street felt they were not being heard. So, after several unsuccessful attempts to develop a city-wide plan, America Speaks, a nonprofit organization that engages citizens in high-impact public policy decisions, stepped in. Its mission: to listen to the people most affected by the disaster. The resulting "Unified New Orleans Plan" set up open forums for public officials to get feedback from citizens, which helped reestablish authorities' credibility. For the first time, the city was able to ratify a roadmap that truly aligned recovery efforts with community need. The forums also helped restore hope and connection in the fragmented community. Today, 93 percent of participants are "co-owners" of the plan and are committed to remaining engaged. (Please see the resource America Speaks: Unified New Orleans Plan.)

Focus groups and surveys to engage with the community

Parramore Kids Zone (PKZ) is a prime example of how a collaborative can use community engagement to get early feedback to set its direction. Before embarking, it staged a series of neighborhood meetings to get input on PKZ's proposed services and marketing strategies, disseminate information, and build resident ownership of the project. To increase attendance, PKZ provided free childcare and food as incentives. As a PKZ staff member reflected, "We never would have been successful if we tried to tell the community what services they needed instead of listening to their suggestions." (Please see Case Study: Parramore for more information on the PKZ collaborative.)

Media to share the message and to engage with the community

When United Way of Greater Milwaukee began thinking about launching what became the Milwaukee's Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative, the agency clearly saw that teens needed multiple reinforcing messages to change their behavior. More was needed, agency leaders realized, than direct education and counseling within the public schools, at nonprofits, and in the faith community. The solution was an innovative public awareness campaign developed by Serve Marketing that aimed to change the conversation among teens, their friends, older men, and parents. Serve Marketing started by holding youth focus groups to understand their perspectives on teen pregnancy. It continued these focus sessions as it developed campaign materials to make sure the campaign resonated with youth. The roll-out began with ads making the case that teen pregnancy affected everyone in greater Milwaukee, due to its staggering economic consequences. Teens literally played a central "role," through a series of provocative ads, radio spots, and even a fake movie premiere. (Please see the resource Milwaukee Strong Babies.) Later, the campaign expanded to engage parents through the delivery of a "Let's Talk" toolkit designed to help them talk about sexuality with their kids. (Please see Case Study: Milwaukee for more information on Milwaukee's Teen Pregnancy Prevention collaborative.)

Next Generation Community Partnership

The types of changes collaboratives are seeking in their communities affect the lives of many people. Therefore, it only makes sense that the community be actively engaged in developing solutions and helping to make them work. Next generation community partnership builds on this principle to involve intended beneficiaries as advocates and participants in creating impact. This type of partnership opens collaboratives up to a world of "natural allies" that can be tapped. For example, to address the challenges of disconnected youth, the people that surround and influence youth, such as peers, parents, extended family, and faith leaders, can be supportive allies of the collaborative and its goals. Even in collaboratives that are not youth-focused, it is necessary to partner with natural allies, who may be residents or community members that can help move the work forward.Examples of next generation partnership

Community members participating in collaboratives

Youth contributed directly to the development of Nashville's Child and Youth Master Plan (CYMP). After all, they have the greatest stake in their own future. From the start, a local high school student served as one of the three co-chairs for the CYMP, joined by several other student slots on the taskforce. The taskforce worked closely with the mayor's standing Youth Council and the students immediately had to overcome some barriers to participation. First, they changed all scheduled meetings until after the close of school at 3 p.m. Next, they gained assistance in transportation to meetings through bus fare waivers. Youth members also took significant responsibility for the work's progress. Among other things, they wrote, administered, and analyzed a large scale survey among 1,000 youth. They helped organize several listening sessions involving hundreds of residents and youth. They also were part of the decision that allowed other community members to interact with the taskforce through a variety of meeting formats, such as small-group discussions and one-on-one exchanges, and ensured that Spanish-speaking translators were at the sessions. (Please see Case Study: Nashville for more information on Nashville's efforts to increase graduation rates.)

Community members as producers of impact

The Family Independence Institute's (FII) work on empowering low-income families is another example of next generation engagement. The effort builds on the insight that low-income families have always worked together to address challenges, using their own assets and resourcefulness. In its latest pilot in Boston, FII invited immigrant Latino women (many from Colombia) to form groups of six to eight to meet together monthly. Each was given a computer and small stipend for reporting monthly data on a wide range of metrics related to the health, education, income, and wealth of their families. The women also use these meetings to discuss the challenges they face, ranging from learning English to paying down debt to helping their children do better in school.

Paradoxically, the FII "program" is really an anti-program: It provides no direction or guidance to the women, and in fact, it has a strict policy not to do so. Families are asked to enroll with a cohort of friends and turn to one another and not to FII staff for guidance. Results have been very positive. Participating Boston families have seen a 13-percent increase in income (excluding FII funds) in less than a year. In the West Oakland pilot, average income rose 27 percent, savings increased over 250 percent, debt was reduced, and children's grades and attendance jumped over 30 percent. FII's founder is quick to point out that African American cohorts did far better than the Asian and Hispanic cohorts, showing that the concept applies beyond immigrant communities.

FII's view is that the positive gains are the result of two dynamics. First, participants share their social capital and know-how, multiplying the benefit for each individual family. For example, the women share experiences about where to find quality child care, how to navigate the school system, and where to find legal advice. Second, by focusing on their own family-level metrics related to health, education, income, and wealth, FII families are more likely to make positive changes. As families take action to pay down debt, they see its effect monthly as they report their data, which gives motivation to take more action, creating a virtuous cycle.

Community feedback for continuous learning

David Bonbright of Keystone emphasizes the importance of what he calls constituency voice (please see the resource 21st Century Constituency Voice). According to Bonbright, "Constituency voice refers to the practice of ensuring that the views of all relevant constituents, particularly primary constituents [beneficiaries], are seriously taken into account in the planning, monitoring, assessing, reporting and learning processes taking place within organizations." This type of feedback provides ongoing data to understand if and how specific efforts are leading to impact. Multiple methods can be used to gather this information, such as large-scale surveys, focus groups, and everyday conversation. (Please see the resource Keystone Constituency Mapping.)

Bonbright gives this classic example to demonstrate the importance of including constituency voice in any initiative:

Agencies throughout Africa and Asia invested $40 million in "tool carriers" so that rural farmers could carry their ploughs, carts, and seed drills. A variety of different programs provided about 10,000 of these tool carriers. Technical experts thought that these carriers would be of great value to farmers. But that was just a theory. The reality was that the carriers were not adopted by farmers in any developing country because the farmers did not think they were a good idea. Not having early feedback was costly to these agencies because they lacked quick feedback mechanisms to receive these constituents’ perspectives (please refer to the resource Keystone Constituency Voice Overview). Mass surveys or focus groups can help to avoid such missteps as well as facilitate the creation of highly targeted solutions that use resources in the best way possible.

Another example from FII highlights the effectiveness of good feedback mechanisms. FII recently incorporated a “Yelp” feedback system to get residents to comment on services in their community. Through this means, those services can improve and community members can begin to see themselves as consumers of services rather than solely as beneficiaries.

And maybe that’s the real benefit from the emergence of these various next generation solutions: to get people actively involved in helping themselves.

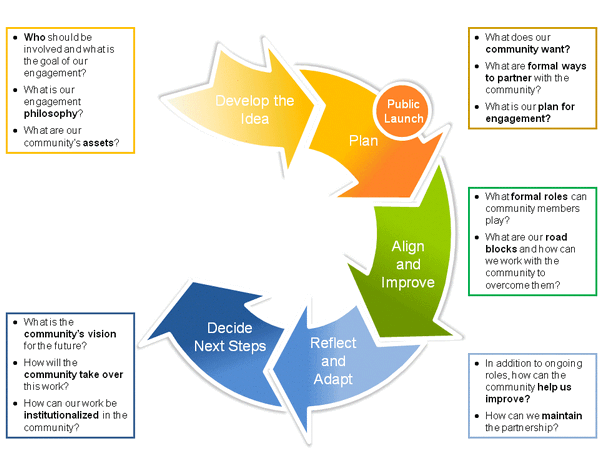

Key Questions to Ask by Life Stage

Community engagement can difficult, but there's no substitute. The diagram below will help you navigate what you should be discussing and when.

Resources

| Name of resource | What suggestions are highlighted? | Who is this tool for? |

|---|---|---|

| Keystone Constituent Mapping | How to identify constituents and stakeholders who should be involved | Collaboratives gearing up to engage the community |

| Keystone Feedback Surveys | Reasoning and tips for using surveys to gather feedback | Collaboratives planning to gather quantitative and/or qualitative data from constituents |

| Keystone Formal Dialogue Processes | Reasoning and tips for using thoughtful dialogue to gather feedback | Collaboratives planning to gather qualitative data from constituents |

| AccountAbility Stakeholder Engagement | Steps for encouraging quality stakeholder inclusivity and engagement | Collaboratives determining whom to bring to the table |

| Keystone Constituency Voice | Explains relationship cycle of community engagement for organizations to follow | Collaboratives at any stage of the community engagement process |

| Harwood Institute Community Rhythms | Assesses community's level of engagement | Collaboratives trying to evaluate the level of engagement in their communities |

| Harwood Institute Authentic Engagement | Evaluates to what degree organizations listen and engage with constituents | Collaboratives that believe they are already engaged to some degree with the community |

| Harwood Institute Public Capital | Identifies resources that community members might be able to offer to collaborative | Collaboratives looking to better involve the community in positive outcomes |

| UC Davis Parent Leadership | Resources for strengthening parental involvement in school-community partnerships | Collaboratives interested in partnerships between schools and communities |

| Ready by 21 Action Plan | Provides a case study of how city leaders engaged a community around a shared vision for youth | Collaboratives seeking examples of successful community engagement, especially around youth |

| UC Davis School Partnerships | Provides detailed guidelines for engaging parents and communities in support of youth | Collaboratives interested in launching a youth-oriented initiative, measuring results, and securing funding |

| IDEO Toolkit | Provides guidance on how to apply IDEO's "Human-Centered Design" to nonprofits | Collaboratives working to understand their community |

| Civic Engagement Measure | Provides tools for measuring the current impact of a community engagement plan | Collaboratives looking to assess the success of their community engagement plans |

Sources Used For This Article

1. The Bridgespan Group reviewed more than 100 collaboratives and conducted extensive interviews with leaders from the 12 exemplary ones. Bridgespan also hosted a meeting with community collaborative and community revitalization leaders and experts to discuss and hear feedback about what we were learning. A number of these leaders went on to take part in further discussions that informed our work and our recommendations, including the content of this guide.