Innovation. The word is so ubiquitous, it’s lost much of its buzz and most of its meaning. Nevertheless, our research suggests that most leaders of nonprofits believe that to advance their missions, they must imagine and create new approaches to solving vexing social challenges.

Recently The Bridgespan Group, with support from The Rockefeller Foundation, surveyed 145 nonprofit leaders on their organizations’ capacity to innovate, which we define as a break from practice, large or small, that leads to significant positive social impact.1 For the large majority of this group, innovation is more than just a catchall slogan—it’s an urgent imperative to which 80 percent of them aspire.

The problem is, just 40 percent of these would-be innovators say their organizations are set up to do so. This gap worries us, because most respondents say that if they don’t come up with fresh solutions to the social sector’s myriad challenges—such as improving the academic performance of at-risk middle schoolers, increasing African farmers’ crop yields, or dramatically reducing the number of diarrhea-related deaths of young children worldwide—they won’t achieve the large-scale impact they seek.

If that weren’t concerning enough, these organizations are confronting a volatile environment that will likely amplify their struggles and widen this aspiration gap. Roughly half of the survey’s respondents say that their organizations are subject to regulatory shocks or policy shifts. (We fielded this survey before the Trump Administration’s federal budget was introduced.) And many others face growing competition from other social sector organizations for funding, talent, and influence.

According to our survey, most nonprofits know that delivering the same services in the same manner is insufficient. But unfortunately, most also struggle to anticipate emerging opportunities for distinctive offerings or approaches that might extend their reach or magnify their impact. Perhaps that’s not surprising. Deviating from the norm—to pursue novel principles, embrace unorthodox thinking, and learn from instructive failure—is difficult. Like their peers in the for-profit world and the public sector, it often takes a crisis for nonprofit leaders to truly break with the status quo.

The answer to nonprofits becoming proactive and effective at innovation lies largely in committing to a continuous, intentional approach. Despite our tendency to celebrate “heroic” chief executives and entrepreneurs, innovation rarely comes from one go-for-broke, masterstroke of genius. For most organizations, meaningful progress against the innovation-aspiration gap requires systematic exploration, experimentation, and trial and error, where learning compounds over time. Innovation is neither magic nor mystery; high-performing nonprofits demonstrate that organizations can deliberately cultivate the capacity to innovate.

Six Elements for Building Innovation Capacity

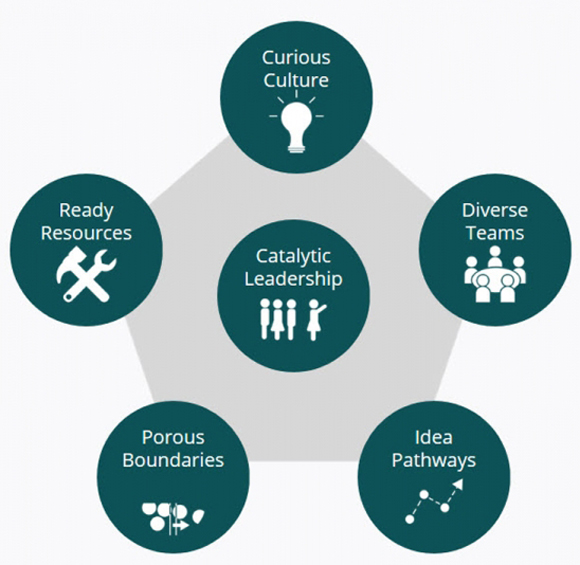

Organizations that excel at continuously generating innovations over time can look very different from each other. They can work in dissimilar fields or deliver poles-apart services; their assets and capabilities may vary widely. But through our research, we have identified six elements common to nonprofits with a high capacity to innovate:

- Catalytic leadership that empowers staff to solve problems that matter

- A curious culture, where staff look beyond their day-to-day obligations, question assumptions, and constructively challenge each other’s thinking as well as the status quo

- Diverse teams with different backgrounds, experiences, attitudes, and capabilities—the feedstock for growing an organization’s capacity to generate breakthrough ideas

- Porous boundaries that let information and insights flow into the organization from outside voices (including beneficiaries) and across the organization itself

- Idea pathways that provide structure and processes for identifying, testing, and transforming promising concepts into needle-moving solutions

- The ready resources—funding, time, training, and tools—vital to supporting innovation work

On average, survey respondents who say they are meeting or exceeding their innovation aspirations also reported doing better across each of these six elements than those who say they are falling short. Although this result is based on self-reported data from a relatively small sample of social-sector leaders, it suggests a strong correlation between these six elements of organizational capacity and innovation performance. The correlation is also consistent with what we learned in interviews with more than 20 leading experts and practitioners, and from a review of academic and professional literature on what drives innovation in organizations.

Element One: Catalytic Leadership

Organizations that consistently innovate have leaders at all levels—managers and executives—who empower teams to push the limits of what’s possible, even as they delineate the boundaries of what’s in play. They understand that innovation flourishes when the need and space for it are clearly defined, and staff are then encouraged to create and explore. Deftly managing the tension between clear parameters and creative license is challenging but critical—more than half of the survey’s respondents rated committed leadership as the most important factor for innovation of all six elements.

Leadership that catalyzes innovation:

- Sets an inspiring vision

- Defines the questions and outcomes to focus on, and then gives people wide latitude to innovate within those boundaries

- Models behaviors others should emulate

Consider Higher Achievement. Based in Washington, DC, and founded in 1975, this nonprofit provides daily academic mentoring, summer learning, and social-emotional skill development to enhance the academic performance of middle schoolers in low-income neighborhoods in four cities: Baltimore, the DC Metro area, Pittsburgh, and Richmond, Va. CEO Lynsey Wood Jeffries and her leadership team do a range of things to spark ideas and initiatives within a clearly defined space.

Jeffries ensures that Higher Achievement uses data as a “flashlight,” which illuminates opportunities to innovate and improve. All of the organization’s 85 staffers regularly review 11 key performance indicators (KPIs), including students’ average daily attendance and current academic performance. Those KPIs frame biweekly discussions between line staff and supervisors across the organization and guide decision-making.

Jeffries and her leadership team, including Chief of Programs Mike Di Marco, provide their colleagues with clarity around where their program model is “fixed,” and where there is “flex” to experiment and adapt. For example, to maintain consistency across its subject matter, Higher Achievement uses one fixed, standard curriculum, which staffers can’t change. But there is flexibility around adding supplemental supports, so long as they align with the standard and meet student-development criteria. So when the data showed that eighth graders were disengaging during the spring semester, after they found out where they would attend high school, a staffer pushed to introduce a study-skills curriculum to smooth students’ transition.

“Instead of having a long conversation about this new approach, she was able to demonstrate that the idea falls within that [flexible] category, and here’s the data to support it—and then it happened,” says Jeffries. “We’re going to test it and if the attendance rebounds, we’ll try it in other sites.”

When the data warrant it, Jeffries asks her colleagues challenging questions that spur them to think big, such as: “What would it take for us to place 80 percent of our middle schoolers in selective, high-performing high schools?” When she sees glimmers of something new working well, she “shouts it from the rooftops and makes sure that people hear that praise.” The result? A randomized control trial showed that Higher Achievement’s programs give children academic gains equivalent to an extra 48 days of learning in math and an extra 30 days in reading.

When it comes to catalyzing innovation efforts, Jeffries says, “It’s my job, first and foremost, to uphold the culture.” We agree. A raft of academic literature and large-scale surveys suggest that culture is central to innovation.2 Through their own behaviors, leaders who aim to innovate can and should shape the organization’s culture, which is the second critical element for sustaining innovation.

Element Two: Curious Culture

To innovate, says Google Chairman Eric Schmidt, “you have to have the culture—and you have to get it right.” More often than not, the “right” culture for innovation is one animated by curiosity. Innovative organizations start their search for something new by asking, “What if?” or the slightly more subversive, “Why not?” As Alan Webber put it in his book Rules of Thumb, “A good question beats a good answer.” Questions are gateways to learning, and learning can often lead to change. Curious cultures encourage staff to rethink their assumptions, recalibrate what’s doable, and reimagine a better future.

Organizations with curious cultures:

- Foster communication, collaboration, and trust

- Encourage critical thinking and debate

- Rethink their physical space

Kiva.org, based in San Francisco and founded in 2005, built the world’s first (and largest) nonprofit micro-lending platform. Kiva uses crowdfunding to provide no-interest microloans to people in 93 countries who want to build better futures for themselves, but who the traditional finance system ignores.

From the outset, Premal Shah and Matt Flannery, two of Kiva’s co-founders, were intrigued by the concept of a “starfish” design framework, where the organization is comprised of relatively independent and autonomous people who take ownership of their work and Kiva overall. They believe their core responsibility is to inspire and guide others by articulating an overall mission and a set of values, asking challenging questions, and empowering colleagues to experiment, take risks, and drive their own ideas. Says Shah: “By providing people with a sense of ownership and psychological safety, we have been able to scale our initial idea and pretty regularly introduce some important new ones.”

One of those ideas is Kiva’s US lending model, formerly known as “Kiva Zip.” Although Kiva is best known for its international efforts, Kiva Zip began funding loans to US based, small business owners in 2012.

The brainchild of Matt Flannery, Kiva Zip was brought to fruition by a small team led by a former Kiva volunteer named Jonny Price, who later joined Kiva full-time to develop the Zip concept. Price is now a senior director at the organization. In a post on Kiva’s blog, he cites one of his favorite quotes, President Bartlett’s oft-repeated refrain in the TV show The West Wing: “What’s next?” Price comments: “I think that’s a great way to approach life.”

Even as a temporary volunteer, Price felt empowered and supported enough to ask “What’s next?” for Kiva Zip. In its early days, the Zip team identified an opportunity for Kiva’s lenders and borrowers to more closely connect with each other—a concept that stands at the heart of Kiva’s mission, “to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty.”

In early 2013, the Kiva Zip team rolled out a “conversations” feature, which enabled borrowers and lenders to talk to each other through the Kiva Zip website for the first time. A Kiva Zip lender in Kenya could post a message to the borrower she funded on the website, and a borrower living in Detroit could reply. These connections often resulted in borrowers receiving support in many unforeseen ways: Some respondents acted as mentors, others as customers and brand advocates.

The Kiva Zip team was also responsible for an innovation in the field of “social underwriting”—that is, banking based on character. Social underwriting relies heavily on social capital to screen prospective borrowers, who must bring a certain number of new lenders onto the platform during a “private fundraising period,” before their loan request posts publicly on the Kiva website. The idea: If the people who know the borrower best think the person is creditworthy, then the Kiva lending community will show up to crowdfund the rest of the loan. This form of social underwriting is especially helpful for immigrants and others with credit histories too young (or nonexistent) to qualify for traditional, small-business loans. Kiva’s US program now generates almost half the new lenders who join Kiva and has sourced more than $25 million in new loans.

Every day, staff across Kiva continue to ask, “What’s next?” As in most contexts, the answers and ideas they come up with are enriched by the diversity of its full-time staff, fellows, volunteers, and partners.

Element Three: Diverse Teams

Of the six elements our survey analyzed, respondents deemed diversity the least important. We believe that’s an oversight. As Gary Hamel observes in his book The Future of Management, when similar meets dissimilar, there’s often a “small frisson” of energy—and the embers of inspiration start to glow. Unfortunately, as Hamel asserts, organizations often train the dissimilarities “out of people, through programs that indoctrinate employees in the ‘one best way.’” Innovative organizations counteract idea-leeching groupthink by building teams that are diverse—not just in terms of gender, ethnicity, and race, but also life and professional experiences, skills, and cognitive styles.

Organizations that deploy diverse teams for innovation:

- Hire people who are diverse across three dimensions: demographics, cognitive and intellectual abilities and styles, and professional skills and experiences3

- Design teams to better harness diversity

- Prepare staff to lead and contribute to teams that are diverse and inclusive

It’s not enough to simply seek out diversity. Even heterogeneous organizations can struggle to achieve true inclusion that gives voice to outside perspectives. Too many organizations hire for diversity, but then onboard staff for assimilation; too many managers favor harmony and agreement over the clash of ideas and perspectives that can unlock promising ideas.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) counters devastating humanitarian crises by delivering services to refugees and displaced people in more than 40 countries. The organization understands that to amplify diversity, it needs to plan deliberately. In 2016, this involved vaccinating more than 173,000 children under age one against measles, treating more than 186,000 children under age five for acute malnutrition, providing 3.8 million people with access to clean drinking water, offering educational opportunities to more than 1.5 million children, delivering job-skills training to 53,000 people, and more. With such a wide scope of mission-critical work, the IRC created The Airbel Center, a research and development lab that helps bridge the gap between the organization’s limited resources and the Byzantine complexity of addressing humanitarian need.

The Airbel Center brings together program-design experts, researchers, human-centered designers, behavioral scientists, strategic planners, and technology specialists from inside and outside the IRC. Its multidisciplinary teams are typically organized as three-legged stools—a program expert, a designer, and a strategist—managed by a generalist. Other specialists sometimes come in to supplement this structure. The teams build prototypes, test them through pilot projects, and scale the most promising, all of which aim to fulfill IRC’s focus, which in 2016 meant serving more than 26 million people.

Austin Riggs, Airbel’s director, believes that “although it’s early days for Airbel, the ideas we’ve been able to develop are strong and compelling, because there are so many different backgrounds in the room.”

Element Four: Porous Boundaries

Porous boundaries widen the scope for innovation, by allowing fresh ideas to percolate up from staff at any level—as well as from constituents and other outside voices—and seep through silos. New insights flow horizontally, from peer to peer, which allows staff to test them in different contexts, recombine them, or use them to reinvent strategies that are nearing senescence.

Organizations with porous boundaries:

- Co-create solutions with constituents

- Crowdsource voices and insights from outside the organization

- Invest in staff, relationships, and systems—internally and externally—that support the fluid exchange of knowledge

Consider Bangladesh-based BRAC, one of the world’s largest NGOs by staff size. Employing more than 100,000 people in 11 countries, BRAC runs a range of services and social enterprises that reach 138 million constituents, mostly in rural areas.4 Despite its sprawling network of programs, BRAC has found ways to keep fresh information and insights circulating throughout the organization.

Through in-person community meetings and tech-enabled tools such as SMS polls, BRAC listens closely to its constituents’ needs and experiences—the seed corn for new ideas. It hosts conferences, such as the Frugal Innovation Forum, to exchange ideas with other organizations and practitioners, and runs large-scale innovation competitions—some just within BRAC, some open to the wider world—to crowdsource ideas. One example is the 2015 Innovation Fund Challenge for Mobile Money, which generated more than 400 ideas on how BRAC could integrate mobile money into its programming and internal processes, so as to promote financial inclusion among its beneficiaries.5 Finally, BRAC’s robust research-and-evaluation department, as well as its social-innovation lab, act as knowledge exchanges that keep far-flung teams up to date on what works and what doesn’t.

Some of these approaches are new, but the focus on listening is not. BRAC’s deliberate efforts to listen to beneficiaries and ensure that information continually flows throughout the organization extends back to some of its earliest experiments, including oral rehydration therapy (ORT), which the medical journal Lancet described as “potentially the most important medical advance of the 20th century.”

The therapy itself is humble: The right mix of salt, sugar, and water to rehydrate people suffering from diarrhea, which is the world’s second largest killer of young children after pneumonia. But it took BRAC years of systematic observation, trial, and error to understand why people were failing to adopt the therapy. Skeptical health workers, the lack of measuring equipment, and misaligned incentives were among the many root causes that BRAC uncovered over time. As a result of its efforts, Bangladesh today has the world’s highest use of ORT, which has helped drive down the diarrhea-related mortality rate among Bangladeshi children under five from nearly 20 percent in 1988-93 to 2 percent in 2007-11.6

Smaller nonprofits are also finding ways to listen more closely to the concerns and ideas of beneficiaries, staff, and other organizations. Plymouth Housing Group, based in Seattle, provides permanent housing and support services for 1,000 chronically homeless people who have exhausted all other forms of assistance. Like many human-services organizations, Plymouth has embraced trauma-informed care. But Plymouth is unusual in its emphasis on participant voice, which forms the cornerstone of its practical approach.

At Plymouth Place, one of the 14 buildings Plymouth maintains, staff and tenants participate in monthly community meetings, weekly check-ins, open mic and open dialogue events (“Come on down, sing it out” is the motto on the billboard), and participant-led projects, which are built into the daily rhythm of life. These practices have enabled tenants to put forward their own ideas, such as the installation of a community aquarium and a rooftop vegetable garden, for enhancing their wellbeing. Such improvements might seem minor to outsiders, but to the aging, often traumatized tenants who brought them to life, they provide a sense of ownership, community, and above all, home. Annual tenant surveys show that over the past two years, Plymouth Place has outperformed Plymouth Housing’s portfolio average on such metrics as overall satisfaction with the building and staff.

Welcoming ideas from outside the organization and encouraging the free flow of information within it is especially critical for nonprofits like Plymouth, which must comply with the rules and regulations of by-the-book, government bureaucracies. Says Kelli Larsen, Plymouth’s director of strategic initiatives: “It’s hard to break out when you’re governed by these strict rules that threaten your funding if you don’t check this box and that box.” Like Higher Achievement, Larsen and her colleagues try to draw a clear line around what is fixed, and then keep searching widely—within the organization and outside of it—for insights and information that can permeate bureaucratic and other constraints.

Element Five: Idea Pathways

As Eric Ries observes in his book The Lean Startup, even though innovation is an “unpredictable thing … that doesn’t mean it cannot be managed.” Effective innovation is founded on a simple theorem: Generate lots of ideas, use consistent criteria and metrics to prioritize among them, invest in those that seem to hold the most promise, and thereby increase the odds that one or two might yield a breakthrough. As Ries illustrates, the minimum viable product (MVP) concept can be an effective and inexpensive tool for pressure-testing ideas: Build a prototype that has a minimal amount of features (for speed and testing efficiency), but is viable enough to work and produce results that staff can learn from.

Based on our interviews and survey results, few nonprofits have introduced such practices. But it doesn’t take an overwhelming amount of planning to set up clear pathways and processes for surfacing, testing, and introducing new innovations.

Organizations with effective idea pathways:

- Generate new ideas systematically

- Test ideas using clearly articulated criteria, metrics, and methodologies

- Prioritize and scale the highest potential ideas

For years, One Acre Fund, which works with 500,000 smallholder farmers in Africa to increase crop yields and maximize profits from harvest sales, approached innovation like most nonprofits do—sporadically and informally. In 2008, its leadership introduced a new crop to its farmer network: passion fruit. But the product rollout flat-lined. Farmers disliked planting the fleshy fruit and even those who grew it had a hard time getting the harvest to market intact.

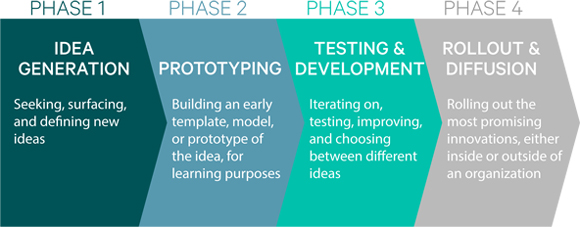

The passion fruit flop was an expensive setback. But the organization’s leaders understood that failure can lead to learning, changing, and improving. One Acre set about developing idea pathways modeled on the practices of leading for-profit, consumer-packaged goods companies. These pathways can be organized around the phases associated with converting ideas into fully fledged solutions:

Idea pathways are best organized around four phases for developing an innovation. (Illustration by Mara Seibert)

Specifically, One Acre revamped how it develops new products, by introducing processes to source, test, and scale ideas. To ensure that new products would be effective, adoptable, and deliverable, One Acre Fund built these goals into its selection criteria. It then developed a clear, multi-staged process—testing and refining in nurseries, small field trials, and larger field trials—to ensure that innovations meet each stage’s criteria before they are scaled out to the full network of farmers.

In 2011, One Acre’s product-innovation team surveyed its network of Kenyan researchers and growers so as to build a list of tree species that might deliver a long-term payoff for farmers. After modeling the potential economic returns of many species, the team agreed that the grevillea tree looked like the most promising, based on the tree’s capacity to grow quickly and improve soil quality (through its leaf mulch).

The team then prototyped the idea by growing the grevillea in a nursery setting. After working through some technical challenges, such as how best to plant and cultivate the trees in different soils, the team moved the grevillea into the experimental phase: live-testing in farmers’ sub-plots. Only after determining that the trees would deliver additional income for farmers—and after resolving all the main uncertainties—did One Acre introduce the grevillea across its network in Kenya, where each farmer planted an average of 50 trees.

By building clearly defined pathways for developing ideas, the organization has introduced a series of new products—in addition to the grevillea—that, on average, have increased farmers’ incomes from One Acre-supported activities by 55 percent.

Element Six: Ready Resources

How often have you heard that innovation emerges when there aren’t enough resources? Google, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Disney, and Hewlett-Packard might have briefly scraped for resources as startups, but they now spend billions of dollars each year on innovation, and they have thousands of employees working on new products.7 These organizations recognize it’s nearly impossible to sustain innovation over the long run without dedicated funding, time, training, and tools. The same is true in the social sector. And if cash-strapped nonprofits deploy some variation of Eric Ries’ “try a little, learn a lot” approach to vetting ideas, they can reduce risk by allocating resources only after a new product or service has demonstrated a high-degree of potential.

Organizations with ready resources for innovation:

- Raise and carve out financial resources to provide flexible funding for innovation

- Structure staff roles to allow a focus on innovation, while also delivering on present programs and operations

- Invest in supporting technologies, tools, and training

Resourcing innovation is hard, even for leading nonprofits. Oxfam International is a confederation of 20 NGOs working in more than 90 countries to eradicate poverty through advocacy, development programs, and disaster relief. With total expenditures of $1.2 billion in 2016,8 Oxfam is larger and better resourced than many nonprofits. But it still struggles to carve out money and time for innovation.

To enable more adaptive programming, Oxfam’s fundraising team works to engage donors on the value of making restricted grants more flexible and to test the potential of alternative funding mechanisms, including Payment by Results and impact investing. These more-flexible funding arrangements and the judicious use of public donations enable Oxfam to invest in toolkits, training, and advisory support for staff, and to provide teams with flexible funding for experimentation. This in turn has given rise to programs that otherwise would not have come to life.

Even with more flexible funding and better tools for innovation, the overriding pressure to deliver on day-to-day work still persists. James Whitehead, the innovation adviser for Oxfam Great Britain, says, “The single biggest challenge for innovation in an organization like Oxfam is carving out time to work on the future, instead of being caught up in the tyranny of the present.”

To address this challenge, Oxfam selects country staff to take time out of their-day-to-day routine and enroll in an immersive experience that focuses on fostering innovation. These “Impact@Scale Accelerators” are designed to support staff in developing new perspectives on their work and in shaping initiatives with the potential to significantly increase Oxfam’s impact, influence, and income. The accelerator in Africa brought together participants from nine countries to develop new initiatives that are in-line with country strategies.

These early initiatives ranged from increasing citizen engagement in the extractives industry in Tanzania to a system-level scaling of innovation in water provision in northern Kenya. Oxfam has also created a fund that provides modest resources to test complementary business models, which include developing an online global learning platform for activists and creating peer-to-peer support platforms.

The results of Oxfam’s accelerators will emerge over the coming months and years. But our research suggests that their overall logic—having certain staff set aside time for the explicit purpose of developing new approaches for achieving greater impact—integrates innovation into an organization’s daily work and sustains it over time.

Innovation isn’t a silver-bullet solution that will automatically make an organization fit for a challenging future. Nor is there a single blueprint for building innovation capacity. Leaders at every level must bring their own imaginations and experiences to the challenge, and figure out what’s best for their organizations. However, our survey and interviews suggest that these six elements are useful starting points for building the capacity to continuously innovate, and thereby do what matters most: improve human and environmental well-being.

This article originally appeared on the Stanford Social Innovation Review website, Aug. 1, 2017.