When Mockingbird Society Board President Hickory Gateless transitioned to the role of deputy director for the Seattle-based youth advocacy organization, he joined what was a relatively new leadership team. The organization, dedicated to ending youth homelessness and transforming foster care, is led by Executive Director Annie Blackledge. Early on in Gateless' new role, Blackledge engaged her leadership team in Bridgespan's Leading for Impact® program, a program which helps leadership teams explore strategic opportunities and build capacity.

"I remember clearly that one of our first conversations during the program was, 'what do we do?' and 'why do we do it?'" Gateless says. Surprisingly, everyone had a different answer. "In answering these questions, it was clear to us that we would all need to have a shared language and shared understanding of what our theory of change was to achieve our mission as an organization."

In this Q&A, Bridgespan Principal Meera Chary talks to Gateless about the process of crafting a theory of change, the decisions his organization needed to make, and the opportunities afforded by its strategy refresh.

Meera: What did the process of revisiting your theory of change look like? What were the roles of different members of the leadership team, and then also outside of the leadership team and maybe even outside the organization?

Hickory: In the beginning we realized that we felt everything we did was important. Our theory of change was an everything-and-the-kitchen-sink kind of situation. But when everything seems important, it's sort of like nothing is. We had to get away from just thinking about what we do and shift to thinking about why we do it.

From a process standpoint, we were new to each other, so people hadn't really taken on roles in the group. As I had said, early on we had a lot of different perspectives on what we do, so I think we did as many groups do: we formed, normed, stormed. Quite frankly, it was the first time our leadership team had sat down together for more than two hours, and it provided a forum to gel as a team. Eventually, we started to lean on the expertise that each person brought, whether it was our policy person talking about how we use our programs to shape policy, or our program person talking about how a program actually functions and works.

Meera: From whom, besides the executive team, did you solicit feedback?

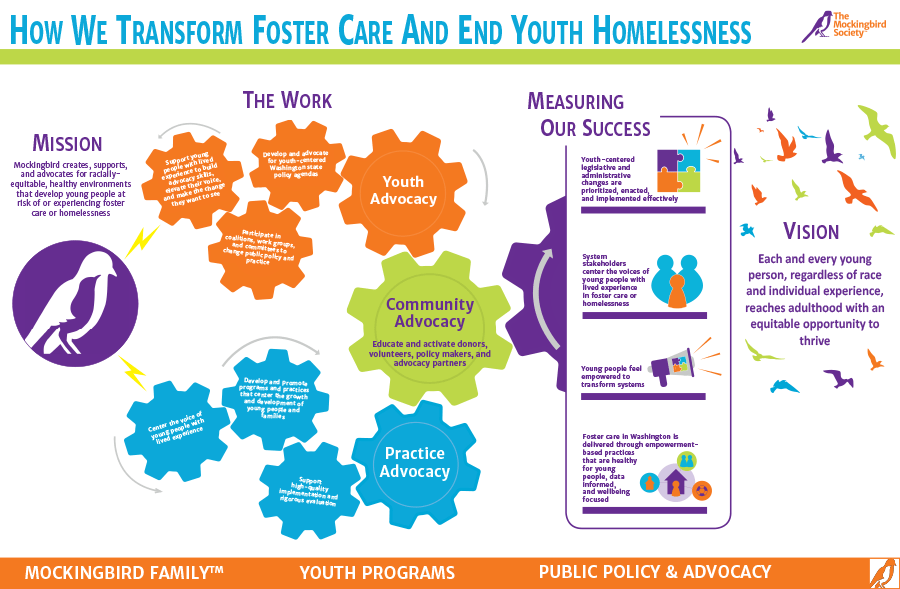

Hickory: Once we came to a good place, we created a compelling visual, blew it up into a poster, and posted it in our hallway. Remote staff printed and posted it, too. Then we developed a process for soliciting feedback from staff, constituents, and the board. Then, as a leadership team, we distilled the feedback and incorporated it. We got everybody's voice on the table and a lot of great enhancements resulted. This helped create buy-in and opportunity for people to feel their voices were heard.

Our youth community also provided input. We have up to six young people on staff as part-time youth advocate employees, all of whom have lived experience in foster care or homelessness. We also had members of seven chapters throughout the state give us their input. There was a lot of good, critical feedback, a lot of which came from the young people that we work with. For example, foster care kids saw themselves on the document, and the kids experiencing homelessness didn't see themselves anywhere. We thought it was there; it just wasn't in the way that they needed it, so we worked through that. As part of that process, they initialed the feedback they left, using Post-it notes. I went and reviewed them all, and then I went to each individual person and had a conversation about their input.

Meera: How did getting clarity on your theory of change benefit your organization?

Hickory: One way is that it has helped us balance our ever-present capacity issue. We're really one of the only organizations in Washington that elevates the voices of those with lived experience [within the foster care and homeless youth systems] to change the way the systems affect those populations. Because of our innovative approach to policy reform, we receive a lot of invitations to participate in different coalitions or bring our work to bear on different policy efforts, so we have to be able to determine when we say yes and when we say no. Having clarity about what is important and what drives us gives us a calculus to answer those questions.

We also had a feeling that we had two very separate tracks of work. We have our youth programs, and we have an approach to delivering foster care that we invented and is being implemented around the world. Our organization had never figured how to talk about those two things in the same sentence. This was an opportunity to integrate those parallel tracks.

Meera: Have you seen any tactical benefits of this process—maybe some of those things that you reflected on at the beginning of our conversation: being able to say yes or no to opportunities, having shared language, etc.?

Hickory: We've seen a couple. One is that our youth programs never felt like they were involved at the front end of our MOCKINGBIRD FAMILY™ work, our foster care delivery model. Now, they are doing trainings and they are doing recruitment from the families to our youth programs. We did focus groups with them around changing the name of our model from the Mockingbird Family Model to just MOCKINGBIRD FAMILY™, and so we were able to invite them into that conversation.

Another major benefit was that it helped us communicate better with funders, donors, and the community. Our website reflects our theory of change—we've started to incorporate some of its language. Our grants now incorporate the language in a way that's approachable. It's helped us make dramatic improvements in our grant writing.

Meera: Do you have any advice for other leadership teams that are diving into theory of change work?

Hickory: It's really important to go beyond just what you do and to think about why you do it. Getting into that depth about your work helps streamline your theory of change. You get to what's really important—it doesn't always mean you give up work, but it does get you focused on what your most important work is and that you achieve the outcomes you want to see.

Another key learning for us was giving ourselves permission to do something for which we can hold ourselves accountable instead of something we'd never reach. We began to give ourselves permission not to hold ourselves accountable to "saving the world," and dial it back to what we can control, what we can hold ourselves accountable to, and what we can measure.

Hickory Gateless is the deputy director of The Mockingbird Society, a Seattle-based nonprofit dedicated to transforming foster care and ending youth homelessness. Meery Chary is a partner based in Bridgespan's San Francisco office and is a member of Bridgespan's Leadership and Organization practice.