Twelve-year old Anna has asthma. She lives in a low-income neighborhood and gets her care at a clinic affiliated with a major teaching hospital. Despite high-quality medical care, Anna’s asthma is not well controlled. Last year she missed almost two weeks of school, had two urgent care visits, and a brief but scary (and expensive) hospital stay. Her pediatrician believes that the old, rent-subsidized apartment where Anna’s family lives may be part of the problem: The presence of mold, moisture, rodents, and dust mites, for example, may trigger her asthma attacks but lie beyond the scope of a clinical intervention.

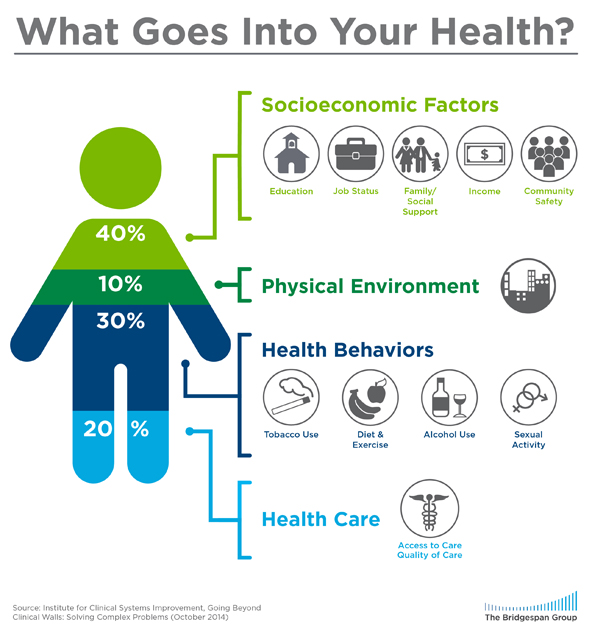

Situations like Anna’s (a composite illustration) are a major factor in worsening health and rising health care costs in the United States. Unhealthy living conditions, nutrition, and a host of social and environmental factors turn potentially manageable health issues into costly ones for both patient and provider. Indeed, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the largest private US grantmaker focused on health, estimates that just 20 percent of a person’s health is related to health care. The rest stems from behavioral, environmental, and social factors. As highlighted by The Commonwealth Fund, asthma symptoms can be linked to where families live; frequent emergency-department visits and hospitalizations can be linked to homelessness; and diabetes-related hospital admissions and other health problems can be linked to food insecurity. In health systems like Kaiser Permanente—one of the largest managed care organizations in the United States—just one percent of the patient population accounts for approximately 25 percent of the total cost of medical services provided annually, often due to non-medical factors.

What goes into your health? An illustration of the impact health care has on a person’s health versus non-healthcare factors.

Physicians themselves see limits to traditional health care in addressing patients’ needs. “Providing the best clinical care for these patients is fundamental,” said Dr. Nirav Shah, senior vice president and COO for clinical operations of Kaiser Permanante (KP) Southern California. “The rest of the solution must include going outside our four walls.”

The good news is that changes in health care financing are pushing some health systems to look for effective ways to address patients’ social needs in the communities where they reside. Prodded by the Affordable Care Act and state reform efforts, public and private payers are increasingly moving away from the traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model—where doctors are paid based on the number of services they deliver, regardless of patient outcomes—and toward a pay-for-performance model, which ties financial incentives to improved health outcomes. Based on this shift, giving a patient a CT scan, for example, may not pay like it used to; keeping the patient healthy and out of the hospital might be more profitable. As a result, forward-looking health care systems are beginning to invest in affordable housing, farmers markets, and other social needs of patients—though at the moment, the great majority of these pilots and experiments are funded through government or foundation grants, or hospital charitable giving.

We are beginning to learn more about how to effectively screen for and address some of these social needs, but we still know too little about how to make the process work across different geographies and diverse populations, and at scale. Indeed, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently launched a $150 million controlled trial to clarify which screening and intervention strategies are most promising.

Larger health systems may hold the key. Our Bridgespan team spoke to a range of health care practitioners and experts to identify examples of large systems seeking to address one or more of their patients’ social needs with core operating dollars—money they previously would have used only for traditional health care services. Three pioneering systems stood out: NYC Health + Hospitals, a public system that serves approximately 1.4 million people; ProMedica in northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan, a nonprofit system that serves 1.5 million people; and KP Southern California, an integrated health system—both payer and provider—that serves 4.1 million patients in Southern California and 10.6 million nationwide. Together, the three systems serve approximately seven million patients, and are seeking ways to sustain and scale their approaches by zeroing in on four decisions:

- Which patients and needs to focus on

- Whether to build or buy the capability required to address patients’ social needs

- How to integrate this work into core clinical systems and processes

- How to measure benefits and costs

While still nascent and not without challenges, their experiences to date suggest that health care organizations can indeed help patients with some of the social needs that have the greatest impact on health.

Deciding Where to Focus

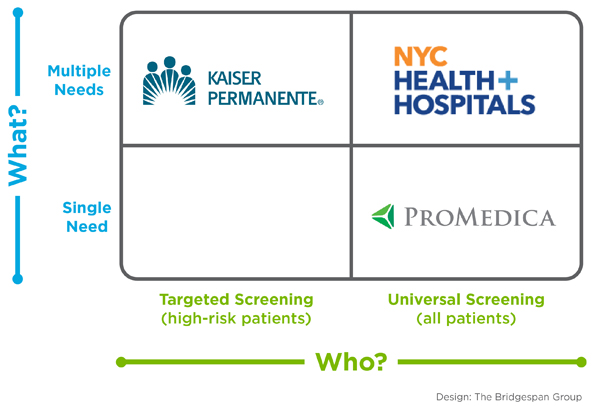

The starting point is determining which patients (some or all) and how many potential needs (one or multiple) to focus on. The following two-by-two figure summarizes this decision point, and the differing choices made by the three health systems we looked at.

Deciding where to focus: a 2x2 framework for addressing social needs based on what health care organizations are screening for (multiple needs vs. a single need) and who they are screening (all patients vs. a subset of high-risk patients).

As operator of a public safety-net system of hospitals and neighborhood health centers, NYC Health + Hospitals knew many of its low-income patients had multiple social needs. It therefore designed a universal screen for multiple needs and partnered with a community-based organization, Health Leads, to implement it. Health Leads, a national nonprofit, places undergraduate volunteers at “family help desks” in outpatient clinics, emergency rooms, newborn nurseries, and health centers, where they collaborate with physicians, social workers, and other care providers to screen patients for a range of needs and connect them to community resources and social services. A recent study from Massachusetts General Hospital shows that interaction with Health Leads is associated with clinically meaningful improvements in blood pressure and cholesterol in adult patients. Health Leads and NYC Health + Hospitals have recently been working to redesign the assessment system so that it integrates with routine pediatric practice.

ProMedica is also pursuing universal screening, but for a single root cause of ill health: hunger and poor nutrition. With conviction that the answer to improving health care lay outside hospital walls, ProMedica president and CEO Randy Oostra asked his board to approve $1 million for a fund that asked community organizations in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan to identify the most pressing needs of those they served, and provided grant funds for interventions to address those needs. ProMedica found a patient population that too often subsisted on pizza, tacos, chips, and soda, and that suffered higher-than-average rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and back issues. Said Oostra, “When you look at poverty, there are so many [overwhelming] issues—education, crime, underemployment, and so on. But hunger [and malnutrition] was something we could get our arms around. We can screen every single patient we touch for hunger.” In the first nine months, ProMedica screened nearly 36,500 patients; 1,500 (4.1 percent) screened positive. The organization is now making a major effort to improve access to nutritious food for its low-income patients, establishing food “pharmacies” (essentially on-site food pantries), offering nutrition counseling, and developing a new supermarket in a low-income area that previously had none.

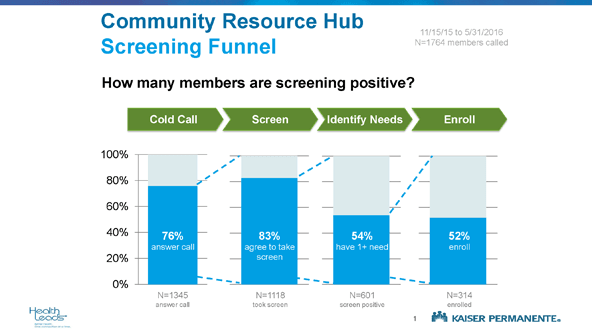

Meanwhile, KP Southern California (which serves approximately 40 percent of KP’s patients nationwide through a network of hospitals and health centers) is targeting “high utilizers” of health care services—the one percent of the patient population that accounts for 25 percent of the organization’s total annual health care costs. The main reason is the potential for significant improvement in health tied to a positive return on investment. Senior Consultant at KP Southern California Artair Rogers explained, “We want to see if we can start showing, in a short period of time, that it makes business sense to invest in this targeted and personalized approach.” The initial screening data from KP’s first group of high utilizers—85 diabetes patients whose medical costs are estimated to be in the top one percent of its entire patient population—found that 54 percent of patients had more than one social need, a prevalence much higher than the KP team expected. This is in sharp contrast to the results from ProMedica’s universal screening (albeit for just one need), which has so far screened in about 4 percent of its total patient population.

How many members to date at Kaiser Permanente Southern California are screening positive for social needs?

These approaches reflect differing local assessments of the tradeoffs between targeting patients who are the highest cost (and who could potentially produce the largest cost savings) or engaging the whole patient population, and between the capacity to address multiple needs or only one significant need.

Deciding Whether to Build or Buy

Another big decision health systems face is whether to build their own capacity for addressing a social need or to acquire it through contractual partnerships with other organizations. Among the three we studied, none of them had capacity to meaningfully address social needs when they got started. In fact, they made the decision to build or buy based on whether they could find effective partners.

ProMedica chose to build much of its own capacity to address hunger after convening a community meeting to identify potential partners and resources, and finding there wasn’t enough existing capacity. It partnered with some organizations already working on the hunger issue, such as the local food bank, and then set about developing some critical new program components of its own.

Two of the components are unusual activities for a hospital. First, its food pharmacies—stocked with donations from the local food bank, unless there are shortfalls, in which case it covers purchasing costs—provide patients with a bag of healthy food for all household members, tailored to their dietary needs. Patients also receive counseling from a registered dietician, healthy-eating handouts, and other information, as well as connections to other community food resources.

Second, the supermarket ProMedica is building in the heart of a low-income neighborhood, where community members identified a severe need for better food access, will be structured for low-to-no margin and subsidize the cost of healthy food for needy customers. The top floors of the building will deliver community programs such as cooking workshops, nutrition information sessions, and possibly even yoga. ProMedica explored the possibility of others taking on this work. “We had several conversations with retailers,” said ProMedica’s Stephanie Cihon, associate vice president of community relations. “While they applauded the idea, the ‘almost nonprofit’ model is not in their toolbox.” (For another example of a health care entity building solutions to patients’ social needs, see “Hospital as Community Anchor” below.)

KP Southern California’s hospital social workers had long played a role in helping patients in need of community resources that would meet their social needs, but the organization wanted greater scale and focus. “This kind of work is very new to our culture,” said Shah. “We want to get better at reaching these people and connecting them to the right places for the social services that will benefit their overall health.” In a scan of community-based resources, Health Leads surfaced as an able collaborator, with a strong track record working with other health systems.

Together, Health Leads and KP are co-designing and launching three pilots in Southern California to identify the best model to scale through the system, building on Health Leads’ in-hospital “help desk” model. These pilots focus on reaching the most high-need, high-risk patients to maximize both health impact and cost savings. KP is not merely buying Health Leads’ model; it’s also buying the expertise needed to help pilot and adapt what it hopes will be a scalable method for addressing basic needs. “We need to turn this from a desk at a few of our sites to a platform across the whole organization,” said Shah, who does not rule out bringing implementation in-house once proof of concept has been demonstrated.

More than anything else, the “build or buy” decision comes down to whether a health system can find a partner that already has the skills and structure needed. ProMedica identified community partners who could help with some aspects of its ambitious food and nutrition effort in Toledo, but built the food pharmacies and the grocery store itself. NYC Health + Hospitals and KP, on the other hand, found in Health Leads a partner who already had the capacity to screen and connect patients to a wide range of social services, and the adaptability to tailor its approach to the specific requirements of the two large health systems. Over time, more skilled partners may develop. Indeed, Health Leads itself was born in the mid-90s out of Boston Medical Center’s need to help struggling, inner-city patients with food, housing, and other needs.

Making Social Needs Interventions Part of Clinical Culture

After zeroing in on the patient population most critical to help, and analyzing whether to build or buy a fitting solution, health systems need to integrate that solution fully with their core clinical systems and processes. As intuitive as integration may sound, many hospitals behave like a restaurant that serves lunch and dinner, but, after identifying demand among its customers for breakfast, merely prints up cards with the name of a breakfast place halfway across town. This referral method is, in essence, how the vast majority of US health care systems seek to connect their patients to non-clinical services, even though “serving breakfast” via integrating the new service with existing operations would be more efficient and effective. Health systems serious about addressing social needs will need to develop supplementary services that share the same places, processes, and people as clinical services.

Places and processes: As novel as ProMedica’s initiative might be for a hospital system, it has worked hard to tie its food and nutrition work to everyday clinical practice. In 14 of its 43primary care practices, every patient is screened for food insecurity using a validated, two-question screen built into their electronic health record. The goal is to conduct screening in every practice by the end of 2016. Patients referred to the food pharmacy can visit it monthly for a total of six months, after which they must get a new referral to ensure that providers remain in the loop and can track results. Because the hunger screening and referral are in the patient’s health record, the organization will know who is coming in, if and when they were referred, and what their cost of care looks like over time.

Even comparatively small steps to better integrate a social needs intervention into clinical systems can produce striking process improvements. NYC Health + Hospitals, for example, is working to expand its longstanding partnership with Health Leads to additional hospitals and eventually other parts of a vast system that serves 1.4 million patients per year, and it’s adjusting processes along the way to achieve better results. At NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue, for example, patients originally completed Health Leads’ basic needs screening tool in the pediatric waiting room—with a 50 percent response rate—and physicians analyzed it later. Now, a primary care assistant helps patients complete the screening tool, or the patient completes it in the physician’s office. The physician then looks at the results during the appointment, and, if needed, makes a direct hand-off to Health Leads staff located right in the clinic. As a result, about 85 percent of all patients now complete the screen.

Building on small practice improvements that more closely tie together clinical and social needs work, NYC Health + Hospitals is ultimately looking for a much more fundamental kind of integration. “We’re trying to learn from the individual elements, then focus and arrange the system around the patient and their family,” said Dr. Ross Wilson, NYC Health + Hospitals's chief medical officer. “There should be one single system. That is the future of this work.”

People: It is hard to move most interventions beyond the pilot phase without the day-to-day support and involvement of doctors, nurses, case managers, and other providers. And both NYC Health + Hospitals and KP want to make social needs screening as routine as measuring blood pressure.

The health systems we studied have invested a lot of effort in communicating with staff about their new social needs initiatives, and have encountered both challenges and opportunities in getting staff on board. The impact of social needs on health makes for “a difficult conversation for medical providers,” says Wilson. “They are trained to think they can improve things. But when there are educational deficits, cultural barriers, extreme poverty—the potions will not work.” Yet Wilson is optimistic that providers at NYC Health + Hospitals are ready to embrace the approach, if the organization can develop the right systems. “Out of medical school, their understanding of the impact of social needs is usually limited and academic. But when they start to work here, they start to understand this.”

Producing a positive, visible effect on both patients and staff could help win over health care personnel. As NYC Health + Hospitals scaled up its work with Health Leads at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue, “the impact was immediately noticeable,” said Dr. Arthur H. Fierman, Bellevue’s medical director of Pediatric Ambulatory Care. “Everyone was happy to have this additional resource to take over the tasks that used to be shared by social workers, nurses, and doctors, or not addressed at all, and to expand the list of things that we could help patients address. This has been a culture change. Now providers can address basic needs in a more active way, and they can feel confident in making the referrals.”

Counting the Costs and Benefits

The three health systems discussed here have—even in the early stages of these initiatives—produced some interesting data on the proportion of screened patients who have reported social need. And while they don’t yet have definitive data on health outcomes, health care utilization, or cost of care, we were struck by the low cost to implement these interventions—in these cases, the costs were usually a small fraction of one percent of each organization’s budget.

“Any CEO of a health care system that says he or she does not have a couple hundred thousand dollars to invest in this work, isn’t leveling with you,” said Oostra. “We build these beautiful, state-of-the-art buildings. So maybe we take out one fountain or a fireplace or some marble, and we put that money into addressing social needs and see what happens.” As Shah further explained, “We’re focusing an inordinate amount of resources, effort, and clinicians’ time on that one percent of the patient population. I can’t afford not to address these basic needs.”

For NYC Health + Hospitals, scaling its work with Health Leads beyond one hospital changed how it thought about costs and benefits. Health Leads, like many nonprofits, had been funding the work through its own donors—providing an important service at no cost to NYC Health + Hospitals. But as the system moved to integrate the work into its business model, it had to rethink whether it could afford to pay for the whole model or whether it needed to integrate certain elements into other care coordination systems, such as social work workflows. NYC Health + Hospitals has funded an evaluation of the Health Leads program to provide guidance about these critical questions of value and cost.

As for assessing return on this investment, both in terms of dollars and health outcomes, KP, like most health systems we looked at, is measuring results by looking at factors like use of health care services, total cost of care, health outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Since KP’s effort focuses on the highest utilizers of care—that one percent—there is some hope that it can realize cost savings, even in the short term, along with improvements in the quality of care. With its food and nutrition initiative, ProMedica is not counting on any short-term cost impact; rather, it is laying the groundwork for estimating return on investment by doing research to establish a baseline for food security, quality of life, and medical care, as well as the cost of that care for a sample of patients.

The recently announced Accountable Health Communities Model—an ambitious effort by the federal agency that runs Medicare and Medicaid to test screening and referral for social needs through randomized controlled trials in dozens of health care systems across the United States—could eventually provide us with much better data on the health and cost outcomes of such social needs efforts. In the meantime, we believe we can learn a lot from the on-the-ground experience of these pioneering health systems as they seek to develop, scale, and evaluate ambitious programs to address the social needs that so heavily affect the health of their patients.

Some of these health systems are seeking to connect their local efforts to a broader national movement. Last year, KP and Health Leads convened a dozen US health systems to explore what role health care should play in addressing social needs. And ProMedica—working with the AARP Foundation, the American Hospital Association, and others—has started the national Root Cause Coalition to engage health care systems, businesses, nonprofits, and government in tackling hunger and food insecurity.

The health care leaders we talked to believe their efforts will impact the bottom line, both in terms of cost and patient health. “At the end of the day, the health care executives have to run the business,” said Wilson. “It is hard to do things you do not get paid for. But in a managed care world, you can start to pay for this. If the work on social needs reduces utilization and emergency department visits, you start to find a business model that is effective.” Bon Secours Baltimore Health System serves residents of a predominantly low-income, African American community in West Baltimore—a neighborhood familiar to many outside the city from the HBO series The Wire and The Corner. As David Zuckerman has pointed out in a 2013 report, hospitals are among communities’ most important “anchor institutions”—their mission, invested capital, and customer relationships bind them to their communities. In the 1990s, Bon Secours, recognizing its outsized role in an under-resourced community, identified housing and redevelopment as a critical need. After researching what support government and community agencies in Baltimore could deliver, the hospital decided to lead an effort to increase access to safe, affordable housing itself. Bon Secours is a classic anchor institution. “We are the primary economic driver for West Baltimore,” Samuel Ross, Bon Secours’ CEO, told us. “There is no one else around.”

Working quietly and using internal funds borrowed from its parent system, Bon Secours purchased 31 of the 67 vacant houses around the hospital before going public with the new strategy. “This was stepping outside the zone,” said George Kleb, executive director of housing and community development at Bon Secours. “It’s unusual for a health system to get so involved in something like this. But if we didn’t engage with the neighborhoods and work with them to get it done, it wasn’t going to happen.” Bon Secours has been pursuing its social needs intervention far longer than the other three health systems we studied, and it has achieved the most substantial scale. Today, Bon Secours has 72 hospital beds, but it also oversees 728 housing units (mostly subsidized, but there are future plans to include some market rate units as well), with the goal of reaching 1,200 units.

Buffeted by an array of challenges that continues to face Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods, including high unemployment and high levels of community violence, Bon Secours’ patients continue to experience health disparities. But there is a visible change in the neighborhood—with only a handful of vacant buildings on the blocks immediately surrounding the hospital. On a recent summer evening, parents could be seen sitting in front of once-empty Baltimore row houses, with their iconic marble steps, taking in the cool evening air and watching their children play. What was once a shuttered school is now a community support center and a hub of activity. Bon Secours housing work is now closely linked to other programs run by a charitable arm of the organization or partner agencies, including education and parenting skills programs, and a workforce development program that has served 1,800 residents since its founding. Bon Secours has even partnered with Health Care for the Homeless to open a clinic in underutilized space within its hospital. In tackling neighborhood housing and community development at this scale, Bon Secours chose not merely to build new internal capacity, but to transform itself into an organization focused almost as much on social needs as on clinical care.