India’s social sector stands at a tipping point. Despite economic uncertainty and the continuing impact of COVID-19, Indian philanthropy has continued to grow.1 Alongside that growth have come new understandings of how philanthropy can make a difference in society – of how funders can have an impact with their gifts.

The immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 focussed on relief, but philanthropy has since evolved towards buttressing the foundations of a civil society that can support the nation’s development. There has been an increase in giving towards developing the capacity of NGOs and investing in long-term development in areas such as literacy and health infrastructure, rather than short-term relief. If givers continue to work towards a new era of transformational philanthropy, the nation’s well-being will benefit.

At the same time, inflows from foreign donors have declined as the Indian economy grew and as changes to the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) restrict foreign giving. With foreign donations likely to continue their decline as a share of total giving,2 India’s individual and family givers – especially those with higher net worth – and corporates will take on an ever-larger responsibility for using their wealth to address some of the nation’s greatest social challenges.

Make no mistake, those challenges remain. There is a substantial shortfall in capital needed to address the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in India. In 2021,India dropped two places to rank 117 amongst all nations in addressing the SDGs. It ranks below four other South Asian countries: Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh.3 The status quo is not making the lives of enough Indians better.

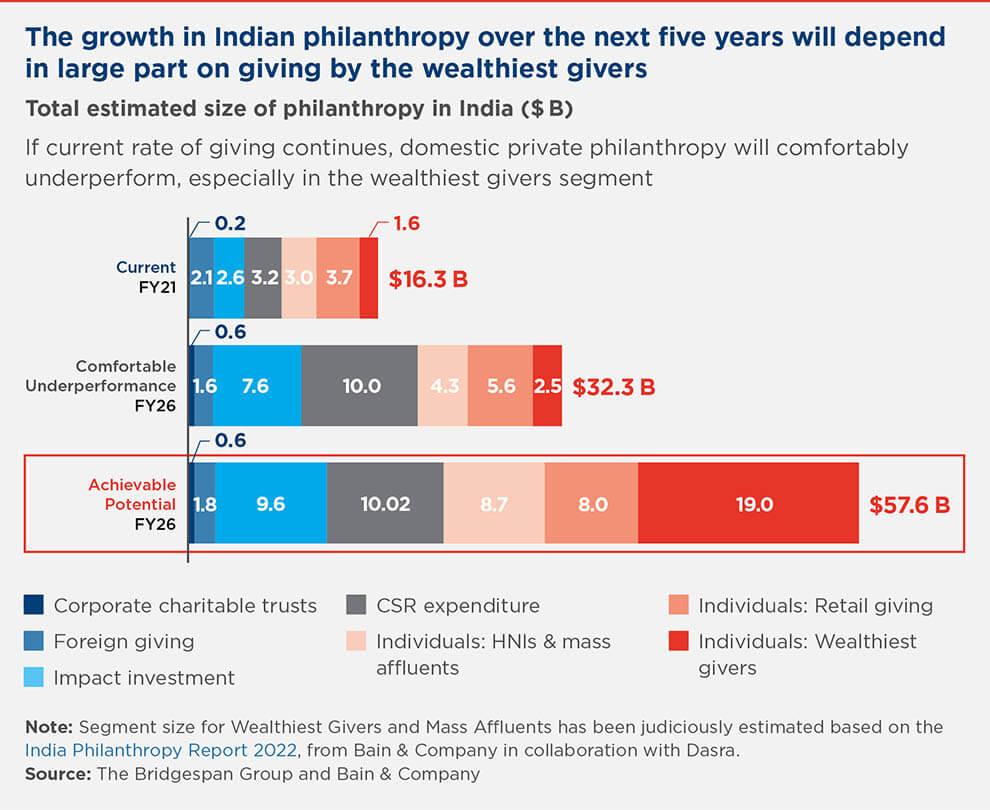

The wealthiest givers will play a pivotal role in whether Indian philanthropy achieves its potential for social impact. Assuming moderate economic growth through 2026, if total giving across all categories of Indian philanthropy grow at their current trajectories, philanthropy will reach $32 billion in 2026, roughly doubling from 2021.

But consider another scenario. What might happen if the wealthiest in India donated the same percentage of their net worth per year as their peers in other nations? That means growing from the current average ratio of giving to wealth from 0.16 to 1.2 percent, using the United States as a comparator. Under that scenario, in which India’s growing middle class and mass affluent also increase their giving, total giving would reach $58 billion in 2026.

In this report on the future of Indian philanthropy, we focus on two especially large and important categories – the wealthiest givers and corporates, through their corporate social responsibility (CSR) investments – and how they can achieve much more impact with their giving. Building on the India Philanthropy Report 2022, published by Bain & Company and Dasra in 2022, we take a deep dive into the giving potential of India’s wealthiest families, having spoken to 61 donors, NGO leaders, CSR heads, and sector experts to better understand what’s driving their giving and how they’re seeking to make a difference. In the next section, we consider whether such an extraordinary level of growth could actually happen and we document some themes that emerged from our conversations.

The short answer is – it could, and here’s how.

The Wealthiest Givers Have the Potential to Give More and Give Faster

The wealth of India’s ultra-high-net worth individuals and families continues to grow dramatically. Forbes reports that the combined wealth of its 2021 list of India’s 100 richest rose to a record $775 billion, up an astonishing 50 percent ($257 billion) from 2020. More than 80 percent of those on the Forbes list saw their fortunes increase, with 61 adding $1 billion or more.4

A fair amount of that wealth building has come from newer enterprises in the technology sector. Hurun’s 2021 Global Unicorn List, which tallies unlisted start-ups with a valuation of at least $1 billion, shows that India overtook the United Kingdom to move into third place in terms of the total number of unicorns (behind only the United States and China). Bain’s India Venture Capital Report 2022 shows 44 new Indian unicorns were minted in 2021 – surpassing China (42 unicorns) for the first time. And public companies are building wealth, as well: The Sensex on BSE (Bombay Stock Exchange of India) rose from approximately 30,000 in 2017 to just under 60,000 by April 2022.

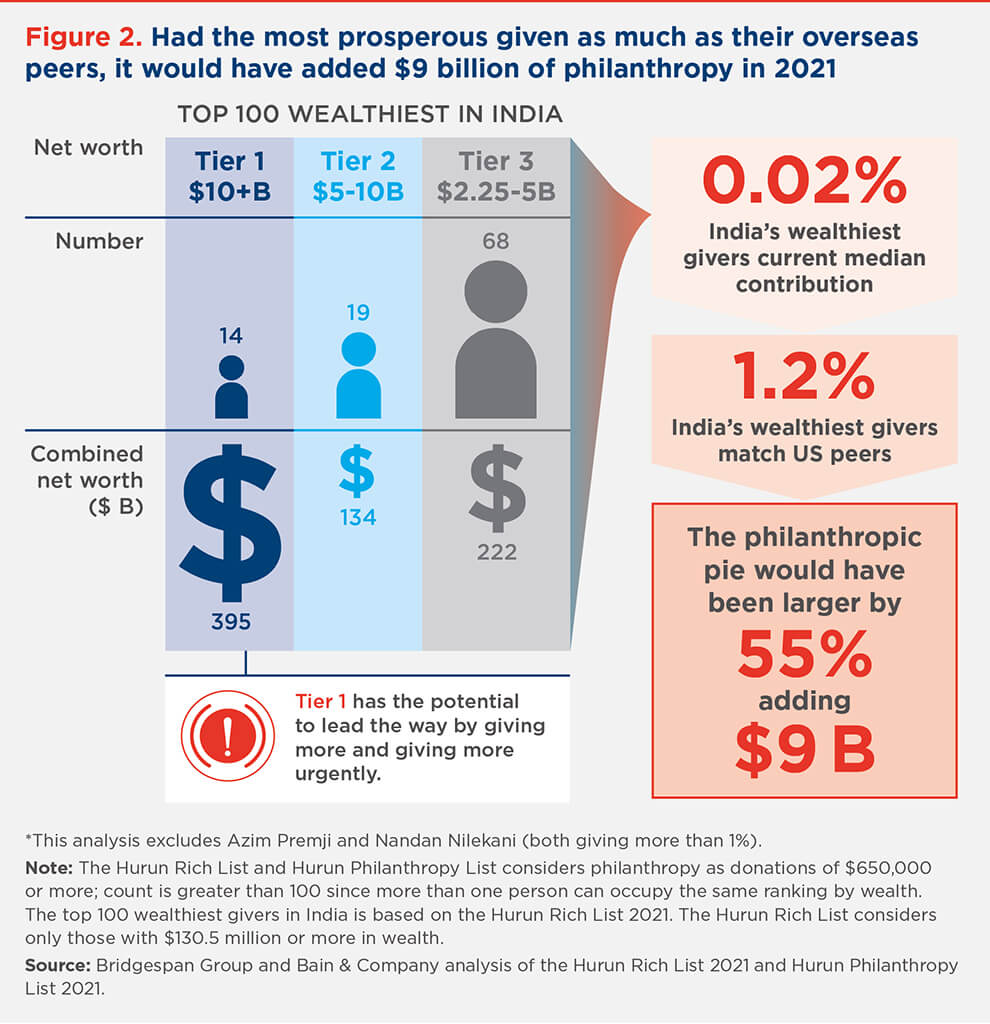

But as wealth has grown, the percentage of wealth that the wealthiest individuals and families are giving away has not kept pace. We believe it is lagging far below its potential. Had India’s most prosperous givers been as generous as those in, say, the United States, it would have added $9 billion to the 2021 total – with more than half of that coming from those with total wealth of $10 billion or more. (To be sure, many observers – including at Bridgespan – argue that this level of giving amongst the wealthiest in the United States is also too low.)

Many committed philanthropists are falling behind in the amount of annual giving needed to meet even their own goals. Signers of the Giving Pledge, created in 2010 by Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett, promise to give at least half of their net worth to charity, either while living or upon their death. As of August 2020, the Giving Pledge had 230 signatories from 28 countries, including 12 from India. However, an analysis of publicly available data for seven of the 12 Indian signers of the Giving Pledge suggests current giving is not keeping pace with the expressed desire to donate at least half their wealth – a situation driven by large increases in wealth not matched by equivalent increases in giving. That signers are falling behind is not unique to India, of course, but the challenge remains, nonetheless.5

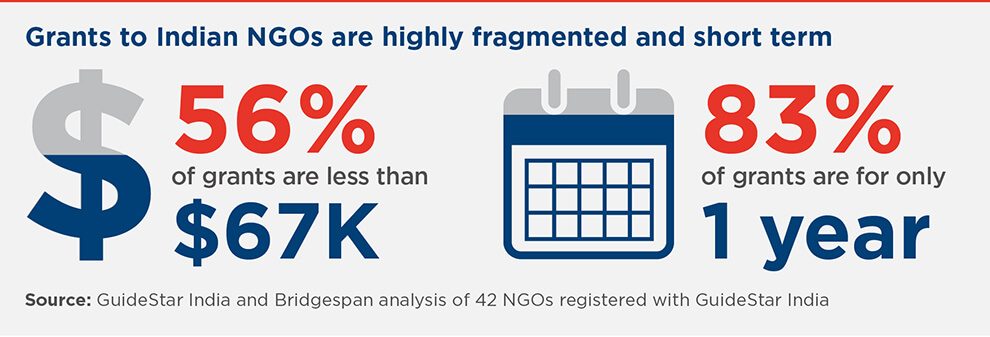

That giving in India is keeping pace neither with growing wealth nor with the expressed intent of India’s Giving Pledgers constrains the social sector. One implication: giving to NGOs in India has tended to be in smaller amounts for a short period of time. Working with GuideStar India (an NGO data and analytics partner for the report), we surveyed 42 Indian NGOs at the end of 2021. The survey data showed that well over half of all grants were for less than $67,000, and that 83 percent provided just one year of funding. It’s difficult to sustain an organisation with such short-term financial stability.

The wealthiest givers give in different ways

Each giver gives in their own way. We don’t claim that the wealthiest donors can neatly be categorised into segments. But in our interviews, we did find three segments that reflect the views of many high-net-worth givers.

Business founder moving on to a philanthropic mission: These givers have handed the reins of their businesses to successors and are making philanthropy a personal mission – shaping and overseeing their philanthropic agenda with the same commitment and rigour as they did their own businesses. Typically, they use a “business-like” approach – grounded in the principles of testing, refining, and scaling. One business leader we talked to speaks of “picking one city, doing the work at saturation, showing impact, and perfecting the model.”

They can also be hands-on. Nimesh Kampani, chair of JM Financial Group, tells us about the time he had put in to work in an area in Bihar, which was outside his home state and which he was not as familiar with. “I visit those places in Bihar three to four times a year. Our efforts to enable local women to develop small-scale snacks enterprises and training them on necessary skills in District Bhavnagar in Gujarat emerged from these visits,” he says.

Younger generation driving philanthropy in a multi-generation business family: Their intent is to create social impact for India, and they expect to make the key decisions and invest the capital needed to get results. The common characteristic is a willingness to experiment and be bold with newer ideas. One such young director spoke of how she and her family are taking a strategic approach to philanthropy, by applying the same learnings and discipline they use to create new businesses towards developing the strategy for their foundation. “I’ve learned from the commitment of my grandfather, my father, and my mother about the importance of creating social impact, whether it is through business or philanthropy. We aim to think boldly in whatever we do, applying the same discipline and vision to philanthropy to address the most urgent needs of the country, and to bring our expertise into strategically intensifying how we are delivering our social and development commitments,” notes Isha Ambani, part of the executive leadership team of several Reliance Group businesses, including Reliance Foundation.

“We have leveraged partnerships from technical, government, and knowledge partners and have also adopted an involved and hands-on approach,” she adds, “so we are not looking at philanthropy as only a donor relationship. [We also] look at how we can contribute our expertise and knowledge to create innovative solutions. We are just scratching the surface of what can happen when we come together in a mission mode; we have built in a spirit of care and empathy across everything we do and want to see the impact of the work we are doing on the most urgent and pressing issues of the time.”

These givers have a very hands-on approach and believe that philanthropy is not just about signing cheques. Roshni Nadar Malhotra, CEO of HCL Corporation and a trustee of the Shiv Nadar Foundation says, “I was fortunate to get pulled in early on in the philanthropic work with my father, and this hands-on involvement was helpful. It is critical that you love the problem and also love the solution, to accelerate towards bolder and more transformational philanthropy. This has proved to be far more catalytic than signing pledges. We have contributed over $1 billion [through today] on our foundation’s philanthropic activities, over and above the company’s CSR. I spend about 50 percent of my time on the family’s philanthropic activities, and a large part of my focus is grooming leadership talent and institution building, keeping the very long term in mind.”

“Self-made” givers (founders and CEOs) adding a philanthropic chapter to their professional lives: They are impatient to create impact at a scale that benefits India, and are willing to take risks and apply the full suite of catalytic approaches, most notably technology, to get there. This group is arriving at a point in their lives where they have both liquid wealth and time to use it for social impact. They believe that, as they have developed management structures in their companies, they can carve out time to work on other causes they believe in outside of their companies. They have role models such as Bill Gates who, in 2000 at the age of 44, started the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with his then wife, Melinda. The common characteristics here are urgency and the willingness to learn from others and actively seek out people who they think know more about the space than them. This group also includes successful CEOs whose equity has made them extremely wealthy. To be sure, there is probably a fourth type, as well: givers from the global diaspora of business leaders, individuals, and families with Indian roots – such as Sundar Pichai (CEO of Alphabet) and Satya Nadella (CEO of Microsoft) – who are looking for opportunities to create meaningful, social impact in India. However, those givers are outside the scope of this domestic report.

Supporting bold missions, not just writing cheques

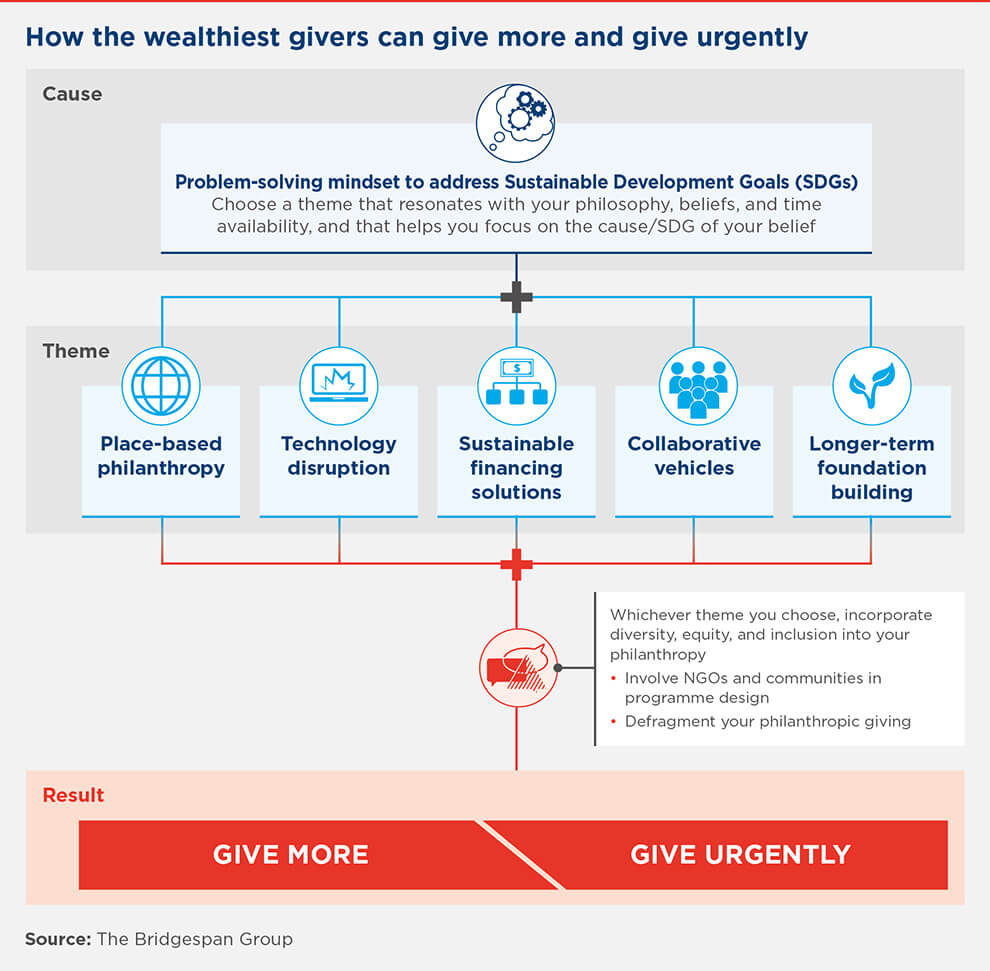

One subtext from many of our interviews is that philanthropists are inspired to give more when they feel their giving is having a real impact. In other words, the “what” and the “how” can drive “how much.” The what and the how are two key decisions. Most of our interviewees were very clear about their what: their focus on a specific cause or SDG. This is driven as much from the heart and personal experience as from analysis or logic.

However, the decision of how they will pursue the cause usually gets less attention. We heard five themes in our interviews to describe the “how” that most inspired philanthropists. We describe them below to help inspire other givers to increase their giving over time and pursue transformative impact. These themes are not mutually exclusive; they very much support one another.

- Place-based philanthropy: Longer-term bets focussed on a community or place, and with a natural appeal to those with a deep connection to their “places of origin.”

- Technology disruption: Appeals to the technology entrepreneur and CEOs. They are technology proponents who are willing to learn and apply their learnings to the social sector.

- Sustainable financing solutions: Appeals to those keen to tap multiple sources of capital in order to finance social impact over the long term.

- Collaborative vehicles: Appeals to groups of philanthropists and corporate leaders keen to combine efforts to pursue bigger and bolder social and environmental goals.

- Longer-term foundation building: The ethos of providing longer-term flexible funding to build supportive capabilities and NGO capacity is more prevalent outside of India. Givers who prefer to be hands-off trust reputable foundations, leaders, and organisations.

Place-based philanthropy

A great deal of giving in India, by wealthier individuals and families as well as those with smaller amounts of wealth, is intensely local and deeply personal. This is the type of giving that Paresh Parasnis, Piramal Foundation’s former CEO, describes to us as, “being driven by the immediate needs of what givers see, whether it’s in their community, whether it’s around their factories, their geographies, or their own understanding.” Trust, transparency, a reputation for impact – these can be critical in helping NGOs attract more private giving, especially at the local level.

Consider Akshaya Patra, which has grown into the world’s largest nonprofit-run midday meal programme since its founding in 2000, serving over 1.8 million children every school day across 14 Indian states and two Union territories. While it receives much funding from the government and corporates, individual giving also plays a big role. And individual giving builds through word-of-mouth within tight-knit local communities.

“A family foundation funded the kitchen in Bhuj,” explains Sridhar Venkat, Akshaya Patra’s CEO. “They also involved their network of friends and family who are now keen to support other kitchens in Gujarat. Similarly, two families funding our Hubli kitchen invited a big philanthropist from their network to visit the kitchen. He ended up giving a large grant to Akshaya Patra. It matters if philanthropists talk about us. People look at references and who is talking about us.”

Technology disruption

India’s burgeoning technology entrepreneurs and the nation’s tech prowess have set the stage for impact-oriented technology investments. Rizwan Koita, for example, the co-founder of CitiusTech, a provider of consulting and digital technology solutions to healthcare and life sciences companies, co-founded the Koita Foundation. Koita Foundation is focussed on two major initiatives – helping NGOs scale and advance their impact and building a digital health network to improve healthcare. Both initiatives involve a substantial use of technology. But, Rizwan Koita tells us, “Technology is not the goal, it is an enabler to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of front-line professionals to achieve higher impact – which is the main goal.”

One of Koita’s partners is the Antarang Foundation, which provides career guidance for youth from under-privileged backgrounds.6 Antarang staff developed career recommendations manually, however, making them difficult to scale. So Koita Foundation worked with Antarang to redesign the process, using technology to scan the student booklets and digitally support developing career recommendations. This has enabled Antarang to scale from 3,000 students a year to 32,000 students.

In its digital health initiative, Koita Foundation is sponsoring a centre for digital health, which is developing health innovations that can be adopted by government agencies, health providers, and patients. In an interview with The Times of India in 2021,7 Rizwan Koita noted the potential of several such technologies. “Can you book an ICU bed at the click of a button? Similarly, which is the best hospital for cardiac surgery in Mumbai? These matrices are just not collected. Digital healthcare will empower patients to make informed decisions.”

Similarly, Arvind Lal, founder of Dr Lal Pathlabs, a provider of diagnostic and related healthcare tests, is upgrading the primary health infrastructure with technology-enabled health and wellness centres – or “Smart HWCs” – to provide access to comprehensive primary healthcare not currently found in the villages of the Almora District in Uttarakhand. The ALVL Foundation, founded by Arvind Lal and his wife Vandana Lal, hopes to provide fundamentally better and affordable basic healthcare facilities at the grassroots level.

Sustainable financing solutions

Sustainable capital is seed capital and the idea of philanthropic seed capital is especially important in systems change – which involves rethinking how a particular system works and seeking a change in how it behaves. Some noteworthy achievements over the past 75 years have involved longer-term philanthropic funding for systems change efforts – resulting in dramatic increases in crop yields, the near-eradication of polio, and a major reduction in the impact of malaria.But seeds can take a long time to grow into trees that bear fruit. Visible gains may be few at first, so philanthropic capital for system change needs to be patient capital. Such grants can sometimes be catalytic – creating an opportunity for other funders, including governments, to come in later with much larger sums.

Another means of providing sustainable finance is blending different funding streams: commercial capital, philanthropic capital, and sometimes public funding. Dvara Trust pursues a blended finance approach in its work to create an ecosystem to reach households and businesses previously excluded from financial services. “Blended finance has been around for a long time, but not that often pursued in India,” says Samir Shah, Dvara’s executive vice chair. “In trying to move the needle on financial inclusion, we realised that a systems approach is required.”

Dvara started incubating commercial companies that could potentially address financial inclusion, but which hadn’t yet realised their markets. Examples include Northern Arc Capital, a debt capital markets platform offering microloans, small business finance, financing for affordable housing, and commercial vehicles finance, and Dvara KGFS, a credit, insurance, and pensions provider in rural and remote India. Once the product fit has been established, the commercial capital can start coming in, with pension funds and wealthy individuals and families the most common sources. Says Shah, “This can be seen as philanthropic capital handling over the baton to commercial capital.” Shah notes that those companies have been able to create sustainable returns over the long term.

Another financing mechanism that has shown promise on a small scale consists of social impact bonds and development impact bonds. These allow investors willing to take on risk to put up initial capital for a programme – they are the risk investors, who are then repaid by another set of funders (it could be governments/donor agencies/philanthropy), once the agreed-upon outcomes are achieved. “This is a largely untested model in India,” says Aloka Majumdar, head of Corporate Sustainability for HSBC India, “The purpose of HSBC using its CSR funds towards outcome funding for the Skills Impact Bond is to demonstrate how such funding can become a catalyst for much wider impact.”

The National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation are providing risk capital of $4 million for the skill impact bond. Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (better known as CIFF), HSBC India, JSW Foundation, and Dubai Cares will provide a combined capital of $14.4 million towards funding the outcomes. The programme will be implemented by five NSDC-affiliated training partners. Dalberg Advisors is the performance manager, while the US Agency for International Development and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office support the bond as technical partners.

“We do see these instruments coming up and we have educated the sector about them,” says Vikram Gandhi, founder of Asha Impact, an impact investing platform. “How do we use social impact bonds and other forms of blended finance? Part of the issue is how do we make them scalable? That’s really the challenge. But we want to think about how within healthcare, education, or agriculture, you can make these things a little more streamlined so they can just scale them up and get the government more involved in this.” Indeed, what we seem to be seeing in India are robust proofs of concept. The key question is how to expand the use of such instruments to many more areas.

Collaborative vehicles

Collaboration in philanthropy is a means of combining efforts while tapping into deep expertise and learning while giving.8 Jan Sahas’s Migrants Resilience Collaborative, for example, is focussed on solving social issues faced by vulnerable migrant workers. The Tribal Health Collaborative is another such collaborative. Created to enhance the nutrition and health of tribal communities, it was co-launched by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Tribal Affairs, and Ministry of Women and Child Development, and supported by Piramal Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.Still, as a 2020 Bridgespan report9 noted, philanthropic collaboratives account for less than 1 percent of total giving in India, despite their potential for addressing social challenges at scale. It found that “comparatively few philanthropies and stakeholders act collectively, not least because it can be challenging to build consensus across multiple partners, negotiate the risk that some partners might fail to deliver, or share credit.”

But the tide is turning. Ingrid Srinath, director of the Centre for Social Impact & Philanthropy at Ashoka says, “coming out of COVID there is a much greater appetite for collaboration. And we’re seeing more structure to these collaborations in India.” Indeed, the number of philanthropic collaboratives in India has more than doubled since 2020.10

Consider the example of the India Protectors Alliance (IPA), created at the beginning of the pandemic by the intermediary organisation Samhita, along with Hindustan Unilever, RBL Bank, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to equip healthcare and sanitation workers with tools to prevent COVID-19 risks on the job. In one year, IPA became a collaborative of 45 companies and foundations who supported the most pressing needs of India’s healthcare and sanitation ecosystem. Its efforts included distributing personal protective equipment to more than 100,000 frontline workers; providing direct cash payments or social security schemes to more than 10,000 sanitation workers; helping more than 1,000 sanitation workers receive entrepreneurship training; partnering with at least 14 state governments to provide ventilators, oxygen cylinders, and other critical equipment; and working to speed vaccination for daily wage workers and low-income communities, who were likely to get left out of the vaccination programme.

Longer-term foundation building

One of the most striking characteristics of Indian philanthropy is how much giving is short term and highly restricted. It bears repeating: 83 percent of gifts received by our survey sample of 42 NGOs were for only one year. As Akshaya Patra Foundation's Venkat notes, "If a child has to study at least 10 years in school, at least five or 10 years of support needs to be there. We need more predictability; we need more long-term giving."

In our conversations with donors, NGO leaders, and sector experts, we often heard about the need for wealthy donors and families to use the flexibility they have in their giving (compared to CSR, which is more constrained by regulations) to strengthen the capacity

of India’s NGOs to address social challenges. This means gifts that are large enough to make a difference, long term enough to have a chance of moving the needle against enormous social challenges, and flexible enough to allow NGOs to put this capital where it can do the most good.

For example, Raj Gilda, co-founder of Lend a Hand India, argues that for efforts focussed on system change, “[We] need to consider the longer-term nature of the work, which can be 10 years or more.” And Paresh Parasnis, Piramal Foundation’s former CEO, tells us that, “We need philanthropists to have a pay-what-it-takes mindset and give grants to NGOs with no strings attached.” For each of the approaches to giving outlined above, gifts that are longer term and less restricted are likely to have the most powerful impact in achieving the goals of donors and society alike.

Corporate Social Responsibility Is Entering the Next Phase of Its Maturation

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds play a large and growing role in overall philanthropy. CSR giving has seen average annual growth of about 13 percent over the past five years and it now represents the second largest source of social sector funding.Still, in interviews with more than 30 corporate CEOs, CSR heads, and sector experts, we clearly heard that while a lot of good work is taking place in CSR, it is far from reaching its full potential.

Ireena Vittal, a former McKinsey partner and current board member of several corporations, sees CSR programmes as mainly falling into two groups. There are traditional givers, like Tata, who were doing CSR long before it became a requirement. “They believe

the role of business is to build communities in places where the firm operates, that the betterment of the community is essential for prosperity,” says Vittal.

Then there are those that started their CSR programmes in earnest only after 2014, when the law requiring CSR investments totalling 2 percent of profit took effect. “There, things are yet to settle. There are staffing and strategic bandwidth issues, plus confusion about

the rules. For most CEOs and boards, CSR is not in their DNA,” Vittel adds.

Some of the philanthropy experts we talked to are cynical about the current state of CSR in India. “It should stand for Compliance Stifling Regulation,” says Noshir Dadrawala, CEO of the Centre for Advancement of Philanthropy, referring to the compliance focus of many

CSR programmes, especially as they seek to understand recent changes in the law.

But others see a maturation process at work. “Yes, CSR 1.0 was very much compliance,” says Srikrishna Sridhar Murthy, co-founder and CEO of Sattva Consulting. “People were getting the house in order – funding what was easy, convenient, and could get them out in the open. Today, I think we are well into CSR 2.0. Compliance is easily taken care of, but what is the real value I am adding to society and for myself?”

Five ways to speed up the maturation process

What could accelerate the maturation process? In our interviews, we heard five themes emerge the most often.Make CSR part of the CEO and Board agenda

The engagement of top leadership can focus CSR giving and inject a longer-term perspective. CSR regulations, in theory at least, support this approach by mandating the establishment of a board CSR committee and a separate CSR team within the company.But some CSR programmes still manage to operate separately from corporate activities – sometimes languishing for lack of high-level attention.

“Move your stars into the CSR team,” advises “Tiger” Tyagarajan, CEO of Genpact, a global professional services firm. “Don’t make it separate from your organisation’s main business.”

HSBC India is one of the corporates we spoke with that significantly engages top leadership in its CSR initiatives. The bank’s CSR Committee comprises of the top leadership and is chaired by the India CEO. Aloka Majumdar, head of Corporate Sustainability at HSBC India, explains, “Community investment or CSR is an integral part of the organisation’s corporate sustainability strategy. The leadership, therefore, is actively involved in the initiatives to ensure we are strategic and focussed with a long-term impact outlook. Be it through

large‑scale initiatives or innovative and results-based finance instruments, such as the skill impact bond.”

Publish metrics to the investor community for greater accountability

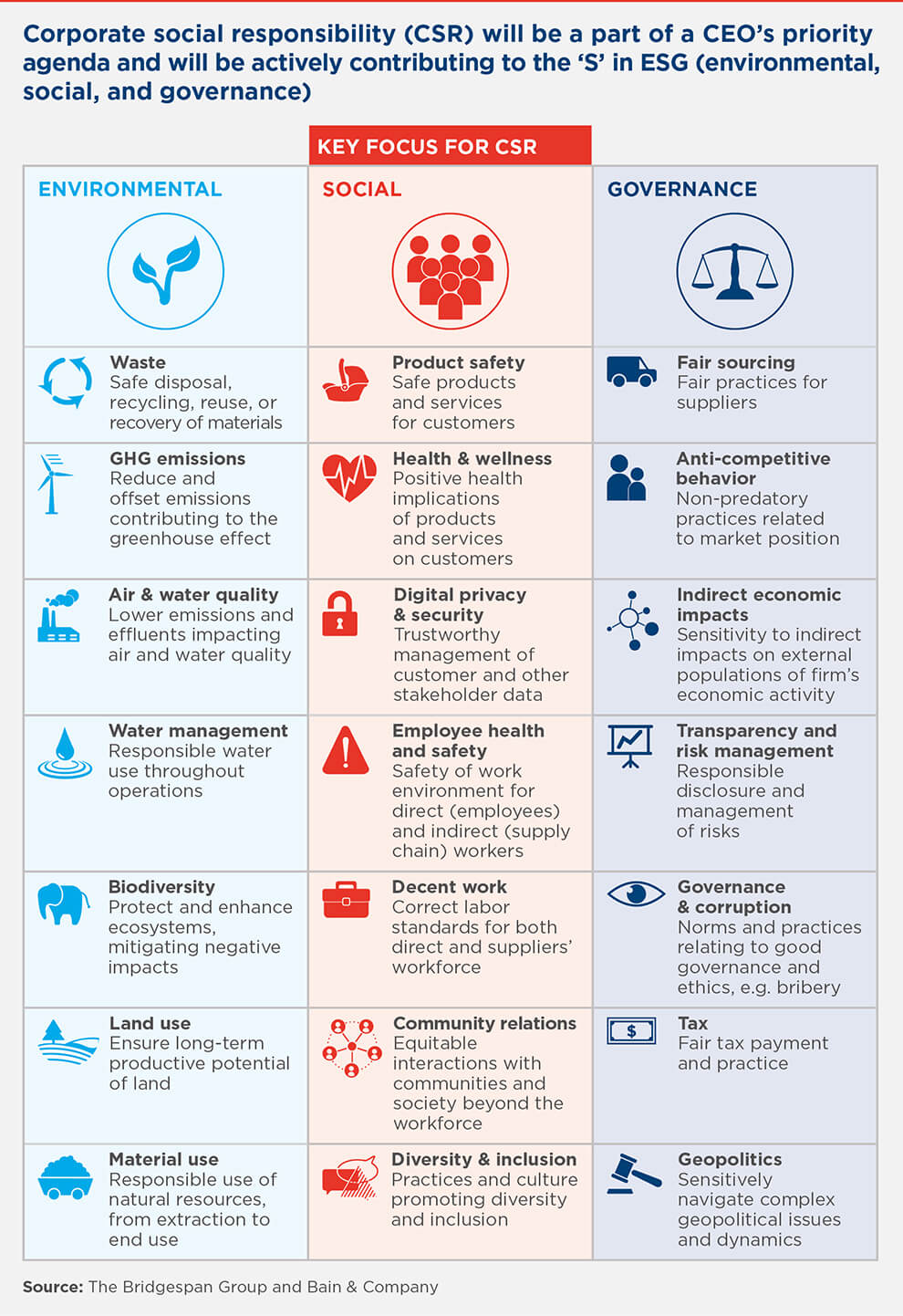

Moving forward, CSR will be linked to the company’s future-looking Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) agenda, where CSR will actively contribute to the social impact of the company as a whole – the “S” of the ESG. It also contributes to the environmentalagenda, of course, but the key focus is on the social. Seen through the ESG lens that is becoming popular in investment and brand analyst spaces, CSR is an important influence on the company’s cost of capital and reputation.

What companies report receives the attention of employees, investors, and other potential stakeholders. So corporates would do well to report meaningful data that reflect how their actions match their values. A data-backed approach with key performance indicators

(KPIs) that measure short- and long-term performance will help corporates evaluate the effectiveness of programmes, identify areas of improvement, and raise confidence amongst stakeholders.

Om Manchanda, managing director of Dr Lal Pathlabs, a provider of diagnostic and related healthcare tests, emphasises “the importance of the investor community being made aware of, and enabled to ask relevant questions about, performance on these social impact metrics as a force for good.” Metrics are a way to ensure CEO and board accountability, which could go a long way towards elevating CSR.

Make strategic choices about the areas with the highest potential for impact

Effective CSR programmes do fewer things well, rather than many things in a fragmented way. Most of the CSR programme heads interviewed for this report described their own programmes as working in no more than three sectors. In addition, they usually havelong‑term plans to create impact within each sector.

Consider Axis Bank Foundation (ABF), the CSR arm of Axis Bank. ABF was formed in 2006 with a vision to enable inclusive and equitable economic growth. In the beginning, ABF was involved mainly in education and then evolved over several years to fund a variety of

social infrastructure projects. However, in 2011, ABF re-focussed on a single overarching goal: creating sustainable livelihoods in a way that would influence the lives of one million people by the end of 2017.

In 2017, it achieved its milestone of supporting one million lives in rural India. “We have remained focussed. Through the last decade, we have evolved our approach and strategy to not only reflect our commitment but also strengthen our work in rural livelihoods,”

says Dhruvi Shah, executive trustee and CEO, Axis Bank Foundation. “Since 2011, ABF has been dedicated to creating livelihoods in rural India. When you work with livelihoods, other aspects of lives are also impacted. Listening to everyday challenges of communities

and remaining focussed are important elements for our long-term funding approach.”

Collaborate with other corporate and non-corporate funders to multiply impact

In the same way that collaboration can strengthen the impact of the work being supported by the wealthiest donors, it can also strengthen the efforts of CSR programmes. As Bridgespan argued in the 2021 report Building High-Impact CSR Programmes in India,collaborations can lead to more capital flowing to programmes than is likely to come from a single CSR programme. And, by sharing common expenses and spreading risks, collaboration can lower the burden on any one programme. Examples cited in the report

include projects by EdelGive and Mahindra. “If we work together on business,” the head of Cisco Social Innovation Group, South Asia, Murugan Vasudevan, told the authors of that report, “then why not also on social projects?”11

Some CSR leaders interviewed for this report expressed interest in collaboration. For example, a key focus of the SRF Foundation (the CSR arm of the SRF Limited) is rural education. It has developed and demonstrated an approach and is now partnering with

other funders to scale the programme, which is now in more than 250 schools. “While our internal budget might be 20 crores [about $2.5 million], we have demonstrated our ability to create a meaningful impact and hence are able to attract long-term partners with

whose help we can enhance this budget to over 35 crores [about $4.4 million]. This helps us scale up our initiative at a much faster pace.” says Ashish Bharat Ram, SRF Limited’s managing director.

Recognise that good for business, good for society, and good for talent converge

“I always believed that an organisation or a business serves four stakeholders – clients or customers, talent or employees, shareholders or investors, and the community,” says Genpact CEO Tyagarajan. “All four are equally important and deeply connected to eachother. That’s why corporates should think about CSR as a part of their overall strategy.”

“If CSR is an independent activity or initiative, it will only go so far,” he adds. “It needs to start from the strategy of the company – what the company stands for, what differentiates it, what excites its people, and should align with the purpose of the company: ‘the relentless

pursuit of a world that works better for people.’ For Genpact, the special multiplier effect of our CSR work is engaging the intellect, time, and passion of our employees. It is not possible to attract the right talent in the future unless one walks the talk.”

This viewpoint dovetails with findings of a global study by Bain & Company which identified “givers” as one of six archetypes of employees across 10 economies. Bain notes that, “Givers find meaning in work that directly improves the lives of others. They are the

archetype least motivated by money.” While often found in professions such as medicine or teaching, they bring important strengths to the corporate world. They account for 17 percent of the total workforce in India.12

Unilever’s HUL subsidiary, whose CSR totalled INR 144 crore (about $18 million) in FY20, making it one of the nation’s top-25 corporate donors, activates those givers internally. “We don’t believe in cheque-signing philanthropy,” says Sanjiv Mehta, HUL’s managing

director and CEO. “We deliver much higher impact by bringing our best talent and capabilities in as well. The key is to link the social initiatives to core business to make the social impact sustainable.”

One of HUL’s social initiatives is Project Suvidha, a hygiene and sanitation initiative focussed on residents of Mumbai’s Dharavi informal settlements. It provides access to affordable drinking water and clean toilets, and also aims to change behaviours around hygiene, such as frequent handwashing, in Dharavi. Handwashing awareness is directly linked to HUL’s hygiene products business. It has top marketing talent working on hygiene and personal care brands, and can leverage their expertise to support behaviour change amongst Dharavi residents. In fact, some of the managers’ KPIs are partly based on achieving specific social outcomes within the CSR programme. “Linking our company’s social initiatives to our core business helps in bringing long-term perspective, and enables us to deliver sustainable, large-scale impact,” says Mehta.

To be sure, Pankaj Ballabh, vice president of CSR at Bajaj Auto cautions that while integrating CSR with broader corporate goals and capabilities is important, CSR shouldn’t simply become another way to get business. As Shri Jamanalal Bajaj, founder of Bajaj

Auto, had advised, “Jaha vyapar karo waha paropkaar ki sambhavana dhoondho, par jaha paropkaar karo waha vyapar ki sambhavana mat dhoondho.” Roughly translated, it means, “Try to find ways to do social good when you do business, but don’t try to find ways to do business when you are out to do social good.”

The Future of Domestic Philanthropy Is Bright

We’ve put a lot of emphasis in this report on the need for India’s wealthiest to play a larger role in the country’s social sector. We are optimistic that the self-made wealthy will come through.Indeed, as we approached publication, we learned of another announcement: Deepinder Goyal, whose unicorn food delivery start-up Zomato went public in 2021, has donated Rs 700 crore ($90 million) towards educating Zomato’s delivery partners’ children. There are

also lower service thresholds for women delivery partners, as well as “prizes” for girls who complete Standard XII. Bolder longer-term bets like this could change the landscape of giving and move substantial wealth towards social change. It’s stories like Goyal’s that leave us optimistic about the future of domestic philanthropy. We hope they inspire you, as well.

GuideStar India provided valuable NGO data and analytics support, for which we are grateful. The authors are also deeply thankful to the teams at Bain, including Ritwik Nimmagadda (alum), Rashish Shingi, Dhairya Shrivastava, Harshit Sharma, Nipun Agrawal, Brigit Thomas, Murphia Pinto, Sitara Achreja, Ishani Pahwa (Marketing), and Jigyasa Khattar (Bain Capability Network), as well as at Bridgespan, notably Umang Manchanda, Joicie Risson, Amantia D’Souza, and Bradley Seeman.

We’re equally grateful to the sector experts and foundation leaders who shared their wisdom and experience with us: