These are times that demand courageous giving to provide essential fuel for social change efforts in areas ranging from public health and the environment to inequality, racial equity, and much more. The ever-rising scale and urgency of the challenges facing our communities and our planet are a clarion call for funders to take giant leaps forward.

This resource list compiles articles and reports on nonprofit sourcing and diligence from the past 20 years.

Sourcing and diligence processes are at the heart of funders’ ability to meet the moment. By “sourcing,” we mean finding and elevating nonprofits and initiatives to fund, while “diligence” refers to the vetting process donors conduct before making a contribution. Together, sourcing and diligence are the means to an important end: providing information for making decisions on giving. But that’s not all—sourcing and diligence processes can also help donors meet and build trust with those who are leading the hard and ongoing work of social change. In addition, they can energize donors about what is possible, helping them see how their support contributes to an arc of impact that is larger than any one individual’s reach.

In this article, we offer practical sourcing and diligence guidance for donors who want to increase their contributions to social change efforts—whether they are just getting started or have been at this work for decades. This information will help donors make their grantmaking more inclusive and equitable, and, importantly, it will help donors get started, “learn while doing,” and improve over time.

The advice is rooted in over 20 years of The Bridgespan Group’s work with dozens of high-net-worth donors and foundations—in communities across the United States and around the world—as well as a literature review and examples from several funders we interviewed for this article.1 We focus primarily on diligence conducted on nonprofit organizations—rather than on individuals, movements, or businesses—while recognizing that there are many ways to deploy capital in support of social change.

To be sure, we come to this topic acknowledging our own missteps. Our early focus on programmatic measurement and on a relatively narrow definition of “what works” led us to initially overlook the potential of efforts that are hard to measure—such as movements and advocacy efforts—and of those without the means to invest in extensive impact studies. We also recognize that Bridgespan’s prior focus on scaling organizations (without also investing in systems and communities) failed to get at the beliefs, policies, and practices that keep historically exploited and marginalized groups at a perpetual disadvantage. Developing this article was a chance for us to pause and reflect on critiques raised by sector leaders—and many of our own staff. We do so in hopes that we can amplify the wisdom of others and share our own evolution and learning, while remaining committed to listening and improving.

We’ve learned how effective sourcing and diligence processes can be when they are designed to counteract pernicious biases baked into common practices and cultural norms. These biases perpetuate longstanding inequities that plague leaders and communities based on their race or ethnicity, gender, caste, class, religion, or other markers of identity.

Effective processes also mitigate the imbalance of power between a funder and grantees, ensuring that the effort and cost of getting to a funding decision are commensurate with the actual funds provided to the nonprofits already doing so much difficult work. From adopting “asset-based” views that recognize the distinct strengths of nonprofits and their leaders to being mindful of the “tax” that diligence processes place on nonprofit leaders, there are practices that can help to advance equity and address power imbalances. We describe these practices below.

Donors come to their giving with a wide range of interests and goals as well as experience with philanthropy. Despite the variety of starting points, we have found they often approach us with a common set of questions, which we address in turn in the sections below:

Where will my giving make the most difference, and how should I get started?

How can I find high-impact organizations and efforts to support?

How will I determine which of those organizations to support?

Whom should I rely on to advise me and manage the process?

Where will my giving make the most difference, and how should I get started?

Have a clear sense of what you want to address—whether it’s mitigating climate change, strengthening democracy, providing affordable housing, or simply giving back to the community where you live and work—while being open to learning and feedback from others.

Bill and Joyce Cummings of the Cummings Foundation knew almost from the start that they wanted mainly to fund the work of local nonprofits in the three Boston-area counties where their commercial real estate company does business.

“Bill and Joyce don’t have a specialized interest. The big focus is giving back in the areas where our staff and leasing clients live,” says Joyce Vyriotes, the Cummings Foundation’s executive director. “In that first year, all we knew was that we wanted to give 50 local grants. We received about 200 applications, and we wound up doing 60 grants.” Their example underscores a few critical points: choosing where to give is often driven by personal values, and the process of giving doesn’t have to be perfect right from the start—it doesn’t have to be complicated, and it can get going quickly.

While the process of giving at Cummings has evolved, its core value of providing broad support for the local community has not. “We’ll find out what the needs in the communities are from the proposals that come in,” explains Vyriotes. “We’re a real estate organization—we know buildings and real estate. We’re not the experts on community issues. We learn a lot as proposals come in.”

At Bridgespan, we sometimes use the term “investment hypothesis” to describe the rationale donors use to direct their giving and clarify the boundaries for their giving. Simply put, this is the donor’s perspective on what will lead to social impact. For example, the Cummings Foundation’s investment hypothesis elevates the importance of supporting high-impact social change locally—supporting nonprofits that do important work in the community but without a specific focus on an issue, organizational stage, or approach to impact.

The Mulago Foundation takes a different approach: it finds and funds “scalable solutions and the high-performance organizations that will get them to their full potential.” Mulago typically starts with early-stage organizations focused on a basic need among people who are experiencing poverty. It systematically assesses an organization’s potential for impact at scale and provides unrestricted funding as long as the organization is making, as Mulago CEO Kevin Starr puts it, “impressive progress toward impact at exponential scale.”

Defining an investment hypothesis will often be deeply personal. Neither a broad nor a narrow focus is necessarily better than the other. What is important: clarifying the values shaping that focus, ensuring a hypothesis can be used as a guidepost for other steps in the process, and staying open to learning as input and feedback from social change leaders, advisors, and peers arrives along the way.

Initially, Jeff and Tricia Raikes, who are Bridgespan clients, targeted their giving toward specific fields, such as youth homelessness and education. As they expanded their giving, it became increasingly clear that the disparate outcomes they sought were the product of a set of “youth-serving systems” that produce inequitable outcomes for students of color. This led the Raikes to evolve their foundation’s investment hypothesis. Racial equity, once a component of the work, is now essential to the vision of the Raikes Foundation. Racial equity is both a focused program area and embedded in every other program area.

“You have to suspend that sense that you have the answers, and really work for proximity,” Jeff Raikes recounts in a podcast for the Stanford Social Innovation Review. “And by proximity, I mean work with the people who are closest to the issue that you wish to address. Understand that their lived experience, which is very different from your own lived experience, is something that really needs to inform those solutions. And if you go at your philanthropy with that form of humility, you’re much more likely to have great impact.”2

How can I find high-impact organizations and efforts to support?

Go beyond your network in a deliberate and inclusive way at the outset to uncover opportunities you might otherwise miss.

In general, we have found that many donors underinvest in sourcing, relative to diligence and other elements of the grantmaking process, because they rely on personal experience and their networks to source opportunities. While personal networks can be a valuable source of recommendations in many aspects of our lives, relying primarily on “who you know” is deeply flawed when it comes to finding ideas for equitable social change. Think about it: no matter who you are, “who you know” cannot be inclusive of the full range of potential leaders and ideas deserving support.

Moreover, in philanthropy, “who you know” leans toward networks in the orbit of institutions that have historically held power in society. In our research on grants of $10 million or more, for example, we found that 42 percent went to organizations led by graduates of Ivy League universities—an extraordinary concentration that matches the disproportionate share of the world’s billionaires that attended just eight institutions.3

As a result, a first step in sourcing is simply to recognize that many of the highest-potential giving opportunities out there may be outside of a donor’s existing networks and will take some proactive effort to discover. There are several complementary approaches to source new opportunities that don’t rely on personal networks. Most donors we know don’t pick a single approach, but rather utilize several and broaden their reach over time.

At every step of the way, it’s important to recognize and work against bias. As noted by many in the sector (and in our own article with Echoing Green on racial bias in philanthropy), multiple forms of bias creep into all parts of the philanthropic process. These may include both systemic biases that affect who gets access to elite educational credentials, as well as unconscious biases that make it harder to build rapport with people of a different race, ethnicity, gender, caste, or other marker of identity. Over time, this produces troubling disparities in the funding available to—and, by extension, the growth and impact of—similarly strong organizations working in the same fields.

Working against these biases starts with the channels used to source ideas and extends to the definitions that determine whether an organization is eligible to be considered. A few proactive tactics include broadening the circle of people who surface and evaluate ideas to reflect the communities you serve, setting demographic goals for your portfolio, and tracking composition at each step of the pipeline process.

Collaborative funds and regrantors

The easiest place to start is often to give through collaborative funds and regrantors. As we noted in a 2021 article, “Releasing the Potential of Philanthropic Collaborations,” “Combining assets should also sound like a familiar tactic: donor collaboratives, in all their many forms, provide donors the same advantages that mutual funds, private equity, and venture capital provide investors—portfolio diversification placed in the hands of specialists.” Donors are often drawn to collaboratives for their efficiency, which spreads the cost of sourcing and diligence across multiple donors; their effectiveness, which comes from the specialized knowledge, skills, and relationships members bring to the table; and the opportunity collaboratives offer for engagement with peers and practitioners.

In some cases, the role of a collaborative is to surface opportunities, from which donors then make their own grant decisions. In others, donors turn over specific grant decisions to an intermediary who manages the fund. And some funds specialize in community-driven grantmaking, in which people directly affected by an issue make grant decisions.

For example, the Trans Justice Funding Project is “a community-led funding initiative founded in 2012 to support grassroots, trans justice groups run by and for trans people in the United States, including US territories.” Each year, it brings together a panel of six trans justice activists to review applications and make grants. Donors who support this fund cede their decision rights, entrusting those with direct lived experience to make the determination of where resources are best put to work.

“It’s a way to join in when you care a lot about a topic, but may not have the knowledge,” says one donor, a former Bridgespan client, of the decision to join a funding collaborative on climate. “And a way to work with others who can put in funding alongside of you. Alone, it can sometimes feel like I can’t do anything meaningful, but … together, I have confidence we are actually working on it."

Open applications

Donors looking to cast a wide net often employ an open application process, finding it a compelling way to ensure any organization can nominate itself for funding.

As Claire Peeps, executive director of the Durfee Foundation, writes in her reflection on open applications, “Every time Durfee opens an application cycle, we meet eligible nonprofits that we’ve never heard of before. It hardly seems possible, but it happens, every time."

With that said, an open call requires careful design and significant capacity to execute in an inclusive and effective way. A donor may find themselves with many hundreds or thousands of applications to review and will need a clear selection process and capacity to do this well. Each application also reflects a significant investment of time and attention from a nonprofit leader and team. In one open application process we looked at, over half the applicants spent more than 30 hours on a 10-page application. Fewer than 5 percent of the applicants ultimately received any funding.

The Grassroots Resilience Ownership and Wellness (GROW) Fund set out to strengthen 100 grassroots organizations doing community development work in India as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold across the nation. In the first few days of the open application process, the fund received significantly fewer applications than expected, which surprised the GROW team given the high level of anticipation around the fund. “On probing, we realized that people have been trained to think certain opportunities are not ‘for them,’” says Naghma Mulla, CEO of the EdelGive Foundation, which developed and promoted the fund.

“In order for this open call to be effective and reach people who are typically excluded,” Mulla continues, “we had a small group of 13 to 15 outreach partners who had wide grassroots networks and helped to accelerate the outreach, organized 12 webinars in English and Hindi with subtitles, and launched print and social media outreach in over 20 languages to proactively ‘market’ our application to specific geographies and groups.” In the end, the GROW Fund received over 2,300 applications, and most of the ultimate recipients were from outside the initial network of GROW and its funders.

A successful open application process involves marketing, eligibility and selection criteria, application questions, and a selection process. Transparent criteria (for example, provided on a website so that potential applicants can self-assess before getting started) and staged selection processes can help ensure that only organizations with a higher likelihood of receiving support are asked to spend more time on the application.

At the same time, regularly revisiting selection criteria and application questions provides an opportunity to sharpen focus on the most critical elements, check for biases, and minimize unnecessary effort from social change leaders. However, note that an open process requires significant capacity to execute, be it from staff, experts from the community or field, or a peer review process (more on how to think about this below).

Proactive sourcing

Another alternative is what we call proactive sourcing, in which donors generate a pipeline of potential grantees, often by systemically reaching beyond who they know. They may turn to nonprofit registries such as Guidestar, seek out organizations based in a particular city or neighborhood, or attend convenings to meet organizations they aren’t familiar with. From there, they may invite those on the list to apply or dispense with a formal application process and move directly into diligence. These processes tend to be more targeted, offering an efficiency many donors appreciate.

But that’s also where bias can sneak in. While a proactive approach is effective for some, it relies on the strength of the referral network, deliberate awareness and mitigation of bias at each stage of the process (including nominations, initial vetting and conversations, and ultimately funding decisions), and staff with the skills and proximity to the issues to build relationships and run the process equitably.

“During my career, I’ve done my best to navigate grantmaking processes as equitably as possible,” says Ryan Palmer, executive director at the Horning Family Foundation and former director of DC initiatives at the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation in Washington, DC (a former Bridgespan client). Following Clark’s wishes, upon his death the foundation decided to spend down all its assets by 2026—creating an urgency to spend its resources quickly and effectively.

“The Clark Foundation is invitation-only, and they were intentional about hiring staff that knew how to connect with folks in the communities that it wanted to fund,” Palmer says. “For example, I grew up in DC, I’ve done community-based work. Invitation-only is fine—as long as you’re able to get out there and find organizations with an equity lens. I talked to everyone and anyone. If you’re upfront with people, then it works out. But I needed to explain to some of the organizations I talked to why we couldn’t fund them, why they didn’t fit with the foundation’s priorities at that time.”

This was also the experience of Isabel Sousa-Rodriguez, the lone program officer for the Edward W. Hazen Foundation, which supports education justice organizing and the leadership of young people from communities of color. Like Clark, Hazen is now a spend-down foundation—committed to distributing all its assets by 2024. Sousa, who came to the foundation after 12 years with the Florida Immigrant Coalition, argues, “You need people on your team who come from the communities you’re funding and who understand the struggles people face.”

Like Palmer, Sousa believes proactive sourcing led by those connected to the issues is the right funding approach. “I understand the arguments for open calls. Now that I’m on this side of things, I completely support not having open calls for our work. You might get 600 submissions and make only 20 grants!"

And while proactive sourcing should yield applications that fit closely with a donor’s investment hypothesis, it is not without its share of deep time investment. When Sousa came to the foundation, she saw that, although Hazen is a national organization, many of its grantees were concentrated in Los Angeles and Chicago. “I was given the green light to find groups in other places. I visited 26 states that year and met with 250 organizations.”

One area of focus was filling geographic and demographic gaps in Hazen’s portfolio—funding Indigenous organizations, foster youth groups, and Asian Pacific Islander groups, as well as organizations in rural areas where the need for support is high and funding often almost nonexistent. “I’d reach out to people with any knowledge of where organizing was happening in these areas,” she says. “I asked our peer funders, and I looked at the docket lists of 15 other foundations that fund similarly to us to see who might fit our criteria.” These energetic sourcing efforts paid off. Hazen went from 23 grantees in 2018 to 54 in 2019.

Variations on proactive approaches include partnering with nonprofits on major initiatives or helping to start new organizations. For example, the Sandler Foundation has provided significant funding to launch new organizations or new initiatives within existing organizations—examples include ProPublica, the Center for Responsible Lending, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. These types of initiatives can lead to significant impact but are feasible only with dedicated staff to manage the work, a high level of confidence that the initiative addresses a sizeable gap, and a commitment to provide meaningful funding that can sustain the work until there are other funding sources to draw upon.

Portfolio approach to sourcing

Many donors take a portfolio approach and use a mix of sourcing channels to complement the expertise, capacity, and networks they already have. For example, The Audacious Project, a Bridgespan client, uses a “lighthouse and searchlight” approach. Its website offers a simple, open form anyone can use to nominate their own organization and idea, or share with others who might be a good fit (the “lighthouse”). At the same time, the sourcing team actively seeks out ideas and initiatives in particular fields and geographies (the “searchlight”). Assuming an uneven playing field when it comes to accessing their channels, the team searches for social entrepreneurs outside of their usual networks.

Says Anna Verghese, executive director of The Audacious Project: “Throughout sourcing and diligence, we try to find organizations that upset entrenched power dynamics, center the communities they serve, and are always learning and adapting. We strive to do what we can given our relative privilege and platform, and yet it is still not enough. We probably won’t ever be satisfied, but we’re okay with that. It motivates us."

This reflects the investment hypothesis of The Audacious Project—powerful and inspiring ideas take many forms, from breakthrough scientific research to criminal justice reform, and require multiple pathways to discover in an inclusive way.

How will I determine which of those organizations to support?

Diligence can provide helpful insight, but grantmaking for social change always involves uncertainty and, therefore, some degree of judgment. Learn to “trust, not prove”—in other words, use the process as a way to build trust with those who are closest to and know the work best.

Once a donor has decided on a focus area and a way to identify potential candidates, the diligence process helps to surface the information needed to make a decision about funding. (There are some good, step-by-step guides to the diligence process for donors—see, particularly, guides from the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society and Grantmakers for Effective Organizations with La Piana Consulting.) There are four key principles to keep in mind, regardless of the approach.

Strive to see strengths and possibilities first—in other words, use an asset-based view.

Since there are so many organizations donors could support, they may be tempted to design diligence processes that screen out organizations from consideration, thus focusing on risk (more on this later) to uncover potential challenges a nonprofit might face. However, we believe the best sourcing and diligence processes are “asset-based,” focusing first on the distinct strengths of nonprofits and their leaders and learning about what works with different communities and in varied contexts.

Starting with a clear-eyed understanding of what an organization does well and where they are differentiated—and then asking, “What supports would this organization need to achieve its impact goals?”—can help a donor determine whether a flaw is a deal-breaker or whether it could be addressed with support. From there, a donor can decide whether to provide support and what kind. This approach opens the possibility for addressing some challenges collaboratively rather than flagging them and walking away. (See the “Resiliency Guide,” developed by the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, for an example of this approach.)

“Through our process, we’ve worked to bring visibility to a wide range of organizational assets,” Dalouge Smith, CEO of the Lewis Prize for Music, underlines. “We’ve now funded two organizations at $500,000 that didn’t have any full-time staff when they got the awards. But when we did our site visits and we met the community of people they were in solidarity with, we said, ‘There is so much human energy here moving in the same direction. The only thing missing is the dollars.’”

Resist the temptation to seek out the “best” grantee.

Given the complexity of most social issues, it’s naive to expect a single player to solve a problem—nor is that likely desirable. This is because attaining true population-level change on outcomes such as driving up college completion rates or driving down reliance on coal for energy will depend not on backing a single winner, but on a whole group of organizations and individuals doing a myriad of good and useful things.

Mulago’s Starr advocates such ecosystem thinking. “Mulago’s biggest accomplishment is helping to advance the professionalized community health worker model,” he says of the Community Health Impact Coalition, a group of more than 25 organizations working together to make the model a norm worldwide. “We’ve funded a lot of other members of this emerging movement. We need to ask, ‘Where are these opportunities to fund related variants on a solution?’ and figure out how to move the whole process down the field.”

Not every donor needs to fund the entire ecosystem. Unfortunately, we have seen donors become paralyzed by the search for a singular “best” when there are abundant resources and multiple organizations that can make good use of funding and, ideally, work together.

Mind the “tax” your process imposes and ensure the potential upside warrants it.

Diligence can unintentionally take a toll on nonprofit leaders that goes beyond the hours invested in writing proposals, answering questions, and hosting site visits. This is particularly true for leaders from historically marginalized backgrounds that may differ from those of many donors. As one Black nonprofit CEO put it, “I expect to answer questions from donors about our work, but there’s a point, after several conversations, at which I wonder if they just don’t trust us. … It’s demoralizing."

For many donors, reducing the “tax” on nonprofits means streamlining processes for small grants, because many processes are too arduous up-front for the amount of funding in consideration. One approach is to provide an initial unrestricted grant after light-touch diligence in order to get to know the organization’s work before considering a larger grant. Indeed, most donors who make “big bets” of $10 million or more have made four previous gifts to an organization or initiative.4

Donors considering larger investments may undertake more intensive diligence, but it is still important to consider the time and effort required of a nonprofit. To that end, some donors have started to offer a funding stipend to all organizations that reach the later stages of diligence to recognize the resources required to even participate in intensive vetting, as well as to help build the relational trust that is the hallmark of a high-quality diligence process.

Reconceptualize to account for the risk of not making the grant.

Many diligence processes use criteria that scrutinize “impact risk” in order to estimate how well likely support will lead to desired outcomes. If there are too many “leap of faith” assumptions, a donor may decide not to fund a potential grantee. Or they may consider a smaller learning grant, which opens a window to better understand the organization, how it works, and whether risks are material.

Other forms of risk are also important for donors to consider alongside the diligence process. (Open Road Alliance has developed a course and diagnostics to help funders clarify their approach to risk.) There is a material difference between understanding financial risk, such as whether this organization has committed fraud; legal risk, such as whether there are open lawsuits or complaints concerning the organization; reputational risk, such as whether the leaders’ public political associations or social media presence are in opposition to the donor’s values; and “impact risk.” Some of these—like reputational risk—are highly subjective, and donors may have widely varying appetites for each type of risk.

Beyond the relatively rare instances of true downside risk (e.g., abusive and harmful practices) that are critical to surface and avoid, it’s also important to weigh sources of risks against the alternative of not doing anything at all. For example, when Florida voters passed Amendment 4 in 2018, they restored voting rights to 1.4 million residents who had been barred from voting because of prior felony convictions—the single largest addition to the nation’s voting population since the Civil Rights Act.

However, for most of the decade leading up to the ballot proposition, funding for advocates was hard to come by, partly because many funders waited until it was clear that the effort had a strong chance to succeed. Their hesitancy had a high price. “The scale of hurt that is caused by incarceration is hard to overestimate,” says Patrick Sullivan of the Freedom Community Center.5 The uncertainty surrounding the early funding for criminal justice reform in Florida might have been a factor to consider and manage, rather than a dealbreaker that delayed funding for years.

Defining and applying criteria for selecting grantees

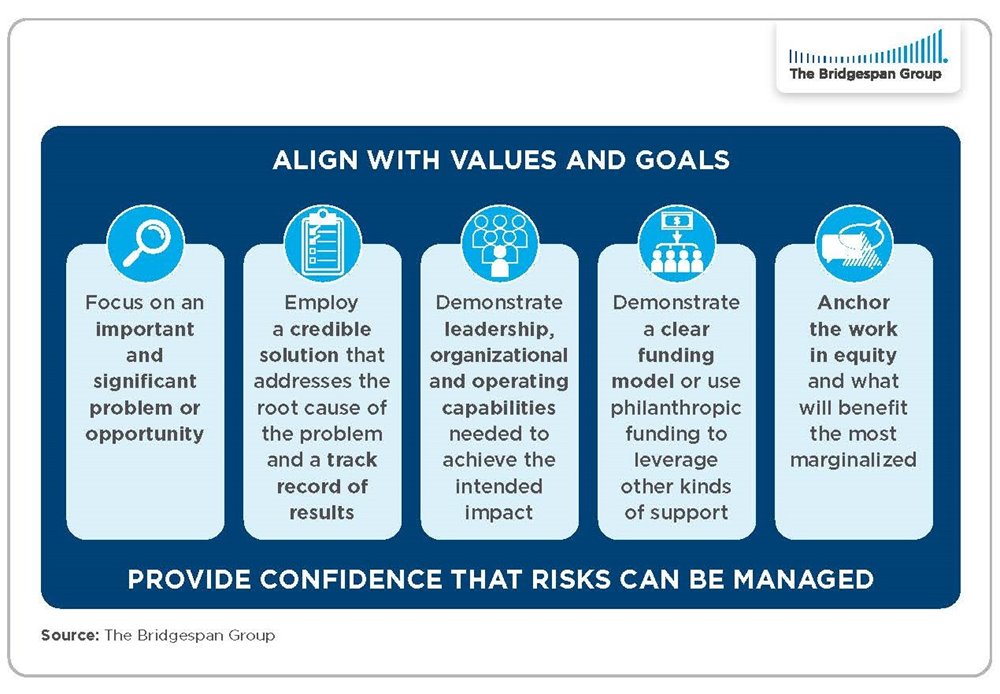

Bearing the four principles above in mind, diligent donors can sit down and define the criteria they will use to select nonprofits and initiatives. As a baseline step, many donors screen for broad alignment with their values while simultaneously exploring potential risks. To decide which organizations to support, we have found donors also use criteria that fall into five categories (see our guide to the “Pros and Cons of Common Selection Criteria“ for more detailed reflections about using criteria in practice). Organizations these donors fund tend to:

Focus on an important and significant problem or opportunity.

Employ a credible solution that addresses the root cause of the problem or opportunity and a track record of results in doing the work.

Demonstrate leadership, organizational, and operating capabilities needed to achieve the intended impact.

Demonstrate a clear funding model or use philanthropic funding to leverage other kinds of support.

Anchor the work in equity and what will benefit the most marginalized.

Each of these broad criteria are inherently subjective. For example, whether a stated problem is “important” or a solution is “credible” can be judged in different ways. While a donor may have experience and perspectives that are important to consider in defining criteria, so, too, do leaders in the field and community. These leaders’ distinct knowledge about achieving impact where they work and live is often a valuable consideration.

Donors vary in how they define each criterion (e.g., what defines a credible solution) and in relative emphasis across criteria. For example, some donors place an emphasis on leadership and role in the field, while others are more interested in an organization’s performance and ability to measure and replicate its results. This means that two thoughtful donors can conduct diligence on the same organization and arrive at different funding decisions as a result of different criteria or weightings.

It’s also common for donors to consider how criteria are applied given the organization’s life stage (is it a startup, or has it proven its success through generations of leaders?) and the field it operates in (is it well-developed, with many proven organizations, or is an applicable evidence base still emerging?).

Donors might also want to think through how their criteria could exacerbate the differential challenges some organizations face in raising funds to build capabilities and financial reserves. For example, consistent underinvestment in Black-led organizations (both their operating budgets and endowments) compounds when donors use criteria like working capital and reserves to evaluate investment worthiness. Instead, donors might consider providing unrestricted funding over multiple years to help build an organization’s capacity versus screening the organization out of any funding at all.

Designing a diligence process that includes relationships and rigor

The diligence process provides a structured way to interpret limited available information about social change efforts to inform an eventual funding decision. A well-designed diligence process is likely a mix of relationships and rigor—braiding together what can be learned through qualitative methods (for example, interviews with staff, other donors, academics, peer organizations, and communities benefiting from the solution) and more quantitative insights from reports and data sources (for example, the organization’s own evaluations, financial documents, and research from the field).

There will still be gaps in information that introduce bias and impede good judgment, especially when considering issues and fields where a donor has limited expertise or experience. For example, if an organization does not have the specific quantitative data point a donor believes would make plain its impact, that doesn’t necessarily mean there is no evidence of impact. It is crucial to proactively mitigate those prospective biases—examining assumptions and using data to identify and counteract them at each step along the way.

While many diligence processes can seem transactional, sound qualitative diligence processes are still about relationships. They benefit from efforts to earn trust and from humble inquiry, and the way questions are asked is just as important as the content of the question. An effective diligence interview with a stakeholder involves asking respectful, well-informed questions; active listening and a willingness to be influenced by what you learn; and awareness of the power dynamics involved in a conversation—in particular, those between a donor and a nonprofit or community partner.

Then there is the quantitative side of diligence processes. There are often specific metrics or indicators that can serve as proxies for performance on a specific criterion. To interpret them accurately, it is crucial to consider the context surrounding an organization’s work (calibrated to the organization’s life stage and field, as mentioned above)—and, most importantly, to find other ways to assess organizations without these attributes.

There are limits to what can be measured, of course, and those limits are different based on field and geography. For example, most nonprofits in the United States are required to file a Form 990 to the Internal Revenue Service each year that includes breakdowns of revenue, expenses, assets, and liabilities. However, financial reporting requirements vary significantly by country; in some cases, public disclosure isn’t required. As a result, a diligence process for a global giving portfolio will need to acknowledge that comparable financial data may not always be publicly available for organizations based in different countries.

Whom should I rely on to run and advise on the process?

It’s hard to give away money without help, and donors make different choices regarding whom they turn to.

Establishing large foundations is increasingly rare: fewer than 20 or so of the roughly 170 American billionaires who have signed the Giving Pledge have grantmaking organizations with more than 50 staff members. Instead, many funders prefer small philanthropic teams to handle not only sourcing and diligence, but also operational and legal needs (e.g., using fiscal sponsors, LLCs, donor-advised funds, and formal foundations).

Here are a few ways donors can get help:

Family office advisors. Many donors rely on trusted wealth management professionals, lawyers, and family connections for their first forays into giving. These advisors can be valuable sounding boards for conversations about principles and values to guide a donor’s giving and can also make connections to other donors who may be grappling with similar questions. At the same time, advisors may have limited knowledge, experiences, and relationships with the social sector. It is often valuable for donors to expand their set of advisors over time, for example, to include voices with proximity to the communities and issues they seek to support.

Intermediaries (philanthropic collaboratives, funds, and regrantors). Philanthropic intermediaries do more than aggregate and disburse collaborative funds. For example, many community foundations provide a spectrum of services for donors, from informal advice to a fully managed fund. Another example is the Climate Leadership Initiative, a collaborative effort that draws upon a network of experts and peer philanthropists to connect new climate philanthropists to high-potential opportunities.

Consultants. Some donors engage specialized social sector consultants (e.g., Arabella Advisors, Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors) to play either a time-bound or ongoing role in supporting the donors’ philanthropy—frequently when they seek a specific capability that is not provided by another intermediary or by staff. (In full disclosure, The Bridgespan Group also provides some of these services.)

Build a team. Staff act as donors’ agents and represent their interests—so they should have a shared understanding of the work, of the role of each staff member or advisor, and of the values and goals that guide the process. Sometimes, staff bring significant experience in philanthropy; other times, they bring knowledge of the field the donor is focusing on or a deep personal relationship with the donor or family.

We’ve seen staff members with field expertise who are brought in early feel constrained by a donor who is still learning and not ready to move quickly. We’ve also seen funders seek to build large teams of experts—only for the team to become a constraint on the pace and scale of giving because of the substantial resources required to recruit, train, and retain staff over time. It can be helpful to start by clarifying aspirations for giving (including pace and scale) and designing the team best suited to meeting these goals.

Many donors mix these approaches because they are working in multiple areas or their needs for support and advice vary over time. Different approaches may suit different parts of a donor’s portfolio of giving, but it is important for there to be a meaningful way for the expertise of community and nonprofit leaders to shape the giving process through these types of support. In addition, a shared understanding of decision-making roles—who provides input, makes a recommendation, and ultimately makes funding decisions—helps focus the work on providing resources to social change leaders versus creating more reasons to delay.

As we move forward here at Bridgespan, we will continue to test, learn, and refine our thinking—just like many of the donors we support. This emphasis on “learning while doing” provides a way to get started without having all of the answers, while remaining laser-focused on what it takes to achieve meaningful impact.

There is extraordinary energy in philanthropy today—a growing desire to do things differently, to tackle head on some of the globe’s most urgent and difficult challenges, and to support the types of organizations and movements that have not often been on the radar of givers. We are encouraged by signals that giving practices—such as providing unrestricted general operating support over multiple years and streamlining funding—seem to be gaining traction with both institutional and individual givers. Early reports from the Center for Effective Philanthropy suggest some shifts may be here to stay.

As many experienced donors have shared with us, the biggest risk is not in picking the “wrong” organization or investing in something that takes a different approach than what a donor initially expected. Instead, the biggest risk is getting stuck while trying to find the “best,” striving to know everything about an issue before getting started, or feeling like one needs to have a distinctive and singular role in social change. It would be hard to do anything if these were a donor’s sourcing and diligence goals.

Committing to give—ideally a specific minimum amount over a particular time horizon—is often a helpful means to push through the temptation to over-analyze and move faster. With a commitment in place, there won’t be time to do all the work yourself and chase the mirage of perfect information. Rather, funders will need to trust the combination of their own judgement and the judgment of others, including those with lived experience, those working with intermediaries, and those with expertise in the field. If funders then adopted entrepreneurial, adaptive approaches to sourcing and diligence, philanthropy has an opportunity to accelerate the speed of trust—and accelerate the impact it has on the world.

Indeed, when we ask experienced donors what advice they would offer to those who are newer to grantmaking, the most common response is “Don’t delay!” The grantmaking process doesn’t end until a funding decision is made, and there is a serious cost to inaction on so many issues—including climate, democracy, public health, and more. The challenges of this moment are tremendous, but so are the possibilities social change leaders can create with the right resources and support.

The authors would like to thank Bridgespan Partner Alison Powell, Editorial Director Bradley Seeman, and Associate Consultant Tiffany Yang, who were instrumental in providing research and insights that deeply shaped this article.