Executive Summary

The COVID-19 crisis has confirmed once again the inequitable design of many of society’s systems. That could be the end of the story, but it doesn’t have to be. Instead, there is an opportunity for funders to respond in ways that reimagine these systems and intentionally lay the groundwork for more equitable ones.[1]

Achieving large-scale, enduring social change of this sort frequently hinges on the work of organizations that serve as “nerve centers” and harmonize the coordinated action of myriad actors. While there may be no agreement on exactly what to call these key entities (e.g., field catalysts, anchor organizations, systems orchestrators, backbones), many of society’s major social-change efforts have benefited from their work.

"There is an approach in philanthropy that looks like fantasy baseball, where you pick a team by looking at the numbers. Our approach is more like going to the park and playing catch."

For instance, consider Freedom to Marry’s work in the fight for marriage equality. It took on a variety of critical roles, from diagnosing and assessing the core problem, to connecting and organizing actors around a shared goal, to being an instrumental advocate, and filling critical gaps across the ecosystem where needed. Similarly, in the current action to end anti-Black violence, The Movement for Black Lives plays such roles as well.

Despite the importance of these special social-change makers, our research and our deep work with clients on large-scale change efforts has convinced us that they are routinely underfunded—often because funders misunderstand and overlook the critical role they play. Traditional due diligence, typically designed to assess direct service programs, is a poor fit for the adaptive nature of their work.

A Different Approach to Due Diligence

We studied more than 20 entities that act as the nerve centers of various social-change ecosystems, conducted more than 30 interviews, and drew from existing literature to distill a set of due-diligence criteria and a process funders can use to assess and invest in these organizations.

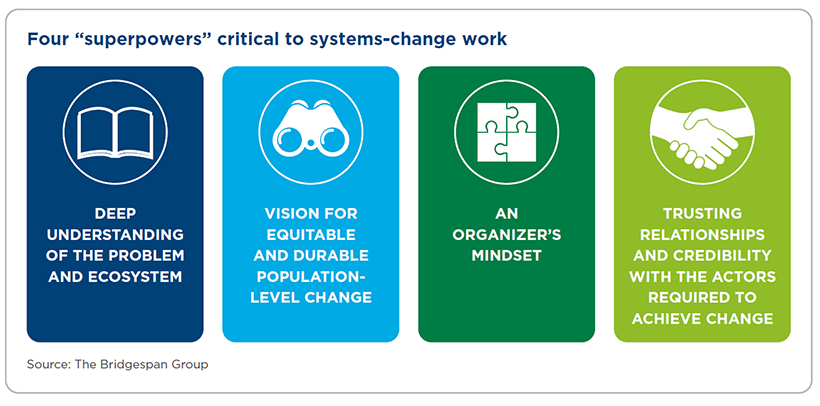

The approach centers on four critical assets, or some might say "superpowers," which make these entities particularly well suited to the complex work of systems change.

The process for assessing these superpowers hinges on listening deeply to the entity’s leaders as well as including rich input from a cross section of the actors with which it collaborates. This represents a significant change for some funders. It requires a shift from funder-driven diagnoses to a vision and shared understanding shaped and affirmed by key actors in the ecosystem. It also necessitates a shift from a transactional relationship between funder and actors devoted to the problem to one of intentional partnership.

As a companion to our article, our guide offers a set of questions funders can ask these types of organizations and other stakeholders to understand the assets they bring.

How to Support this Work

Beyond due diligence, there are multiple ways funders can adapt their grantmaking practices to support the work of these organizations and even “till the soil” for future ones. Among the most critical:

- Providing flexible, multiyear support, which is critical to allowing these organizations to do the adaptive long-term work necessary for change of this sort;

- Funding in ways that foster collaboration (not competition) among actors, including providing resources for convening;

- For issue areas where no viable nerve centers exist, supporting current and future leaders—especially leaders of color—to do this kind of work.

Funders can also interrogate their own biases for what good looks like. One funder noted the need to name their power and privilege[2] and recognize the ways in which their own implicit biases can affect which entities they choose to support.

Building equitable and just public systems is really about imagining another world. Funding field catalysts or anchor organizations or systems orchestrators or whatever else these critical actors may be called is, in part, how we fight for that. And that work deserves urgency not only right now, when our broken systems are so clearly on display, but, frankly, always.