A few years ago, the leadership team of Chicago's Instituto del Progreso Latino faced a challenge familiar to many nonprofit leaders. The then 40-year-old organization was experiencing financial pressures, and it had to figure out how to rebalance its portfolio of programs.

Instituto serves Latino immigrants and their families through a range of programs including economic and workforce development, adult basic education, youth development, and legal aid. It especially focuses on individuals with great potential who are often underserved by traditional education systems.

"We offered a lot of services," says Ian Sharping, Instituto's chief quality officer, "and there was an open question as to where we should focus our efforts among our programs, both to get us on a stronger financial footing and to make the greatest contribution to our community. As an executive team with some newer members, we weren’t fully aligned on these questions."

Instituto used a tool called the program strategy map, which helps nonprofit leaders take a fresh look at their programs. The program strategy map is a visualization of each program’s financial sustainability and its fit with the impact the organization is pursuing, generally with specific populations of focus in mind. Steve Zimmerman and Jeanne Bell, who have written extensively about this type of analysis through what they call a "matrix map," emphasize that it can help staff, board, and other key stakeholders "see the whole organization at a glance in a way that focuses attention on activities and impact."

We believe that mapping programs in this way is both highly valuable and greatly underused by nonprofits. This article draws on the example of Instituto and on what Bridgespan has learned from supporting Instituto and dozens of other nonprofits in using this process, including direct service organizations, advocacy organizations, and organizations with a hybrid of approaches. It’s an introduction to the program strategy map and how the map can inform decisions about growing, improving, or exiting programs.

Developing an Organization's Program Strategy Map

Like Instituto, many nonprofits operate multiple programs or services, sometimes across multiple sites, and find themselves facing decisions about which programs they should grow, which they should try to improve, and which they may need to scale back or even exit altogether. Nonprofit leaders often begin by asking two related questions:

- To what extent is what we are doing contributing to the impact we seek?

- To what extent is what we are doing financially sustainable?

These are hard questions, even for an organization with strong financial analysis capabilities and clear outcome goals. The challenge often leads leaders to make decisions in isolation—looking only at a single program facing a critical moment.

By contrast, using a program strategy map, an organization can visualize how each of its programs contributes to its dual bottom line. The map illuminates powerful tradeoffs, such as, "if we did less of Program A, could we better allocate our unrestricted funds to Program B, having greater impact?" A leadership team can use a program strategy map to assess its programs in comparison to one another. And the assessment doesn’t take place in a bubble; it considers who else is doing similar work, and how the organization’s own programs fit into the larger landscape of services and needs for the people and communities it serves.

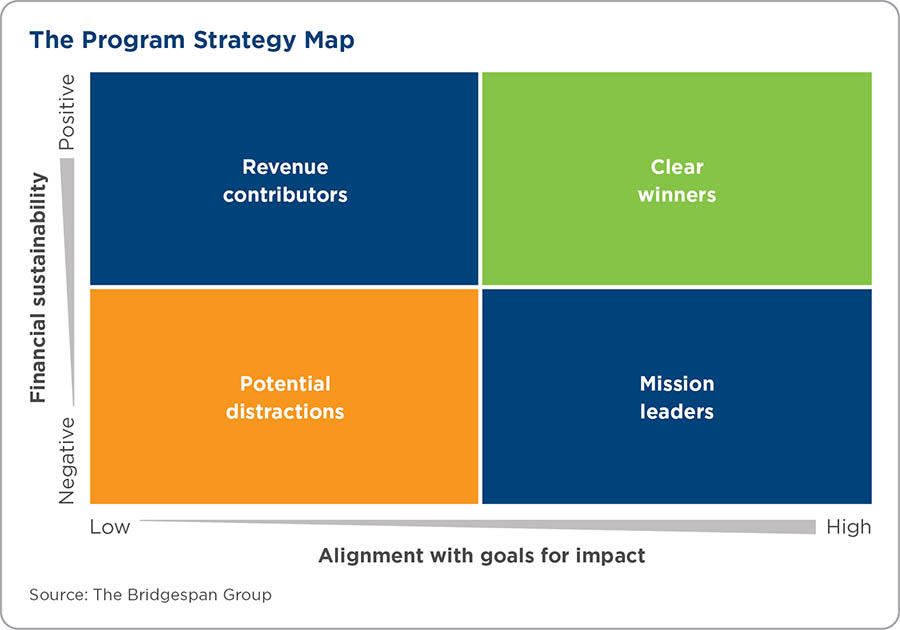

The vertical (Y) axis of this map reflects financial criteria—typically the current net financial contribution of each program and the extent to which funding can be sustained in future years. The horizontal (X) axis shows how each program measures up to the organization’s outcome goals, using criteria such as the extent to which it serves its population of focus, and whether the program is achieving its intended results. (For more on how organizations can think about these goals for impact, including the importance of elevating equity considerations in the goals themselves, see "What are Intended Impact and Theory of Change, and How Can Nonprofits Use Them?").

Our "Guide to Using a Program Strategy Map" and the "Nonprofit Program Strategy Mapping Template" can help you visualize and evaluate your programs in the context of your nonprofit's strategy. Click here to download both >>

Watch: A video tutorial introduction to using the Program Strategy Mapping template.

Each program is plotted as a circle on the map based on its relative position on the two axes. The size of that circle is typically informed by the program’s annual budget, providing a third dimension of data.

The upper-right quadrant of the map contains programs that are "clear winners." These programs are both contributing to the organization's impact goals and are financially sustainable without the addition of unrestricted funds. Those in the bottom left, on the other hand, may be "potential distractions"—programs that aren’t well aligned with the organization’s impact goals and that require additional unrestricted funding to break even. The other two quadrants—upper left and lower right—contain programs that do well on one of these dimensions but not the other. The map provides a clear picture of an organization's impact and economics. "How do we move our programs up and to the right on the map" can become an organization's mantra.

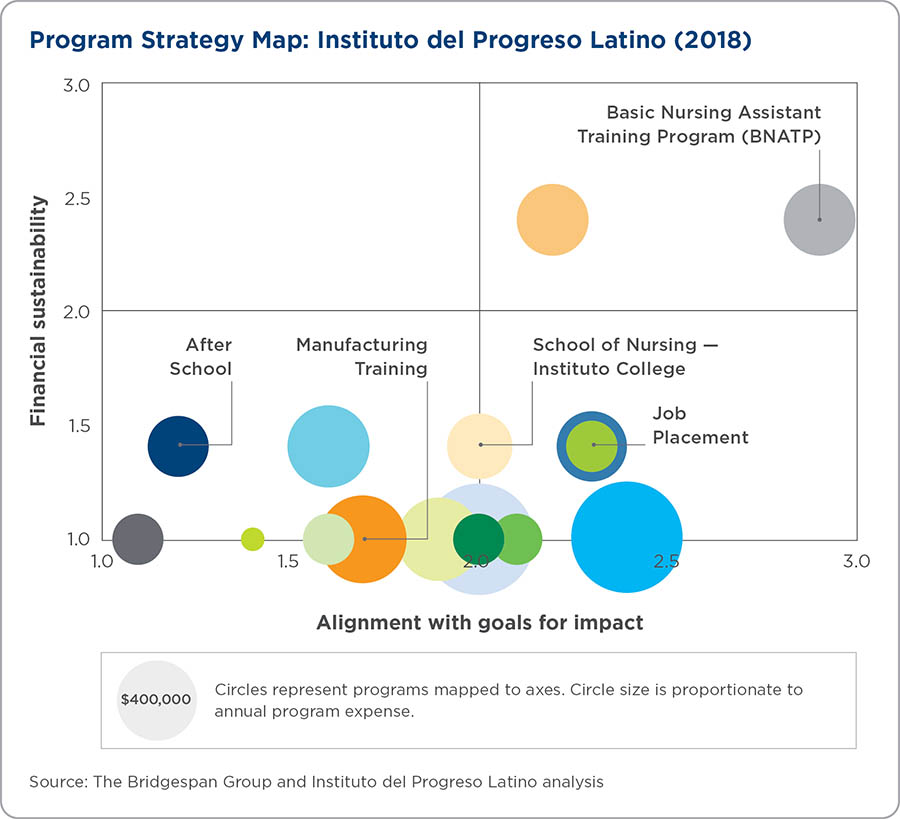

Let's look at how Instituto, which faced a budget deficit and had a relatively new leadership team, looked at its close to 20 separate programs using the program strategy map. In conducting this analysis, the organization coordinated closely across its leadership team, finance, and program leads. It also considered the extent to which its various programs were serving Latino immigrants and their families, especially those underserved by traditional systems (Instituto’s populations of focus); using the kind of approaches that it believes can lead to impact; and achieving the organization's impact goals.

In developing its map, Instituto didn't have all of the data it needed at its fingertips. But it used what it had, and in some cases was able to get more fairly quickly. The analysis takes some time to do, but it doesn’t have to be overwhelmingly complex or get bogged down in a search for perfect information. Each criterion has a scoring method, usually just yes/no or low/medium/high. For more help on the suggested criteria and scoring system, see "Guide to Using a Program Strategy Map."

Here is Instituto's completed program strategy map:

At a glance—and unsurprisingly for an organization with nearly 20 programs—the map appears complex. Yet even without knowing much about the organization's programs, a few things jump out. Instituto did not judge any of its programs as generating revenue but having limited impact (top-left quadrant). It has two programs it judged as being strong in terms of both funding and impact (top-right quadrant.)

Most of the action is in the bottom half of the map: there are a large number of programs that require, rather than generate, funding. They range from a weaker fit with outcome goals (the bottom-left quadrant) to a stronger fit (the bottom-right quadrant). "We weren't surprised about the two programs that landed in the upper right," says Sharping, the chief quality officer. "The analysis was valuable for charting the programs that fell in the middle. And the underperforming programs—those were a little more surprising."

While financial constraints prompted Instituto to take a hard look at its full portfolio of programs, an organization doesn't have to be under pressure to want to map its programs. Other organizations conduct reviews of their program portfolios because of changes in their communities, an infusion of growth capital, or (as was also the case with Instituto) new leadership. In other words, a program strategy map makes sense any time strategic decisions are called for.

From Analysis to Action—Using What You’ve Learned to Make Better Decisions

Many people have had the experience of getting on an airplane for the first time and being surprised by how different things look from the air. Patterns of land use and geography become visible in a way they aren’t from the ground. Similarly, the program strategy map provides a sort of aerial perspective on an organization’s programs relative to one another. While it can't tell you what decisions to make, there are some common choices that leaders may face. Focusing mainly on Instituto del Progreso Latino, let's look at the types of decisions that can be informed by this analysis, especially those related to growing, improving, or exiting programs. To be sure, simply leaving a program "as-is" is also an intentional decision that can be informed by this process.

Program growth: Instituto's Basic Nursing Assistant Training Program (BNATP) looked like a clear winner: aligned with the organization's goals and financially stable. The program is for aspiring nursing assistants who want to work in a healthcare site like a nursing home, hospital, or long-term care residential facility. It has helped many Latino students get a job with the potential for advancement. Although Instituto’s leadership already knew that BNATP was strong, seeing its performance relative to other programs underlined that strength. "When we saw that BNATP was in the upper-right quadrant, we wanted to think about both how to keep improving the economics and also how to reach more people," explains Karina Ayala-Bermejo, Instituto's president and CEO. "We made a conscious effort to expand it, knowing that the program had a waitlist." Instituto decided to tie BNATP more closely to its new School of Nursing program at Instituto College, so there would be a stronger pipeline to a college degree. Instituto also added a platform to deliver online content that helps prepare BNATP participants for training in their medical lab. The program now operates five days a week, allowing for an additional cohort of students.

Program improvement: A program strategy map can also help identify ways to improve a program, whether to align better with the focus population, create more impact, or strengthen financial sustainability. When focusing on programs that are financially sustainable, or close to it, but not doing as much to meet the organization's impact goals as they should (upper-left quadrant), the goal is to move these programs to the right. This could mean increasing the number or changing the types of participants to better serve the population of focus, or making design changes to improve program outcomes.

For example, in its education and job readiness work, Instituto ran several support programs in areas such as job placement. Looking at how these programs landed on its program strategy map, the team hypothesized that they could improve outcomes by creating a more seamless experience. Instituto changed its service model, organizing services around a caseworker who could walk a person or a family through the various services and act as a single point of contact. In the process they streamlined the typical student's journey, from requiring as many as seven meetings with program specialists before starting classes to just two touchpoints: with an intake specialist and with a caseworker.

For programs that are aligned with the organization's impact goals but are less financially sustainable (lower-right quadrant), improvements will likely focus on economics. When Instituto saw that some of its government-funded programs were financially less secure, it set about learning more about their overhead and other indirect costs. Armed with this data, the organization was able to successfully renegotiate with its government funders to significantly raise its indirect cost rate, improving the programs' financial sustainability. Another program that scored comparatively poorly was Instituto's manufacturing training program, which over time had declined in financial performance. The organization shortened the length of the program and reduced the number of certificates it offered. These actions shrank the cost of running the program while still meeting its goal of preparing students for entry-level manufacturing jobs with the potential for advancement.

Program exits: For programs that end up in the lower-left quadrant, scoring less well than other programs on both financial contribution and alignment with organizational goals, leaders may ask whether the organization should be operating the program at all. More than a few of the organizations that we have worked with on program strategy end up exiting programs. Program exits are hard, but can be healthy—freeing up resources to invest in the organization’s strongest programs. Instituto exited two programs.

One was its public benefit enrollment program, helping connect clients to benefits like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program resources, and public or subsidized housing. The program strategy map showed that these services weren’t being delivered all that effectively. Other organizations were better at the work. So Instituto closed down its own benefit enrollment program and partnered with organizations already doing the work, which ultimately led to better services for Instituto clients.

Making the decision about an afterschool program for middle-school students, the other program Instituto exited, was harder. Instituto runs two charter high schools. It thought the after-school program would be a feeder into the high schools, but it wasn’t working out that way. The program’s enrollment was decreasing, and it did not align all that well with the organization’s mission. "Closing a program is one of the most uncomfortable things a leader needs to deal with," says Ayala-Bermejo, the president and CEO. She notes that early communication with staff and parents was critical, as was determining whether other organizations had similar programs. "We reached out to families to let them know as far in advance as we reasonably could," adds Sharping. "You want to give them the opportunity to find other programs."

Maintaining programs—even those that don’t score well on the program strategy map: A program strategy map offers insight, raises questions, and provokes discussion. It doesn’t spit out answers. Programs that score lower than others—even those in the "potential distractions" quadrant—may be worth maintaining for strategic reasons. And programs that score in the middle or high range, but aren’t a priority for growth, may be worth leaving "as-is."

This may be especially true for programs that serve harder-to-reach individuals, need more time to achieve impact, or occupy a unique niche. Indeed, leaders or program staff might fear that scoring on such hard criteria will lead to programs serving the most vulnerable ending up on the chopping block. This is a reasonable concern and ought to be acknowledged at the outset. But nonprofits can also decide upfront to use criteria that prioritize the hardest to serve populations and identify gaps, ultimately helping them advance goals for equity.

In reviewing the results of its analysis, Instituto saw that its college—which had only a school of nursing, but planned to ultimately issue Associate Degrees in other applied sciences—did not score as highly as many of its other programs. "The college has always been one of those question marks," explains Ayala-Bermejo, "because the financials were not where they needed to be." Yet it serves a population ignored by most other schools—what Ayala-Bermejo calls "triple nontraditional students" who have gone into the job market and are coming back to school, live off campus, and typically are single mothers or raising a family. The college’s largest funder understands that it will take time to reach a stronger financial footing. It has helped Instituto expand opportunities for students to get services to help offset some very difficult financial circumstances they face. "The college anchors our commitment to health equity," she says. "We were committed, at least for a time, to improve it and see it through."

Other organizations we have worked with have had other reasons for keeping programs that the analysis has identified as potential distractions. Some may help connect an organization more closely to important constituencies. For example, a program revolving around a well-loved annual event that neither makes much money nor aligns with the core work, might still bring the organization closer to community members. Other programs may afford an organization's leadership "a seat at the table' with peers, which can be particularly valuable for leaders whose organizations serve marginalized communities. And still other programs might be in an early stage of development, with lots of room to improve. If an organization decides to keep a program that fares comparatively poorly in this analysis, it is helpful to explicitly name the rationale for keeping it, set limits on the level of investment it will receive going forward, and look for opportunities to increase its impact over time.

Using a Program Strategy Map to Evaluate New Opportunities

There is no avoiding the reality that mapping programs requires time and effort from an organization's leadership team and staff. But once this work is done, the methodology and insights can be used later on to very quickly assess new program opportunities that may arise. When COVID-19 came, for example, Instituto was faced with some big decisions about what it was going to do—not only how it would adapt existing programs to a new environment, but also whether it should take on some entirely new work that others were pressing it to take on.

"We already knew that eradicating the cycle of poverty was our intended impact," says Ayala-Bermejo. In March 2020, as COVID-19 was beginning to have a huge impact on Chicago, Instituto surveyed its clients, who said that the most important things to them at that moment were food and income security. The organization started a food bank, which it had never considered doing before. "In making this decision, we looked back at our matrix analysis [that is, its program strategy map] and asked, 'did a foodbank fit?'" she explains. "Alignment with mission, short-term financial sustainability—check, check. It was a very quick cost-benefit analysis. Our clients needed this right now, and we could make it work financially."

Instituto partnered with the Greater Chicago Food Depository, the US Department of Agriculture, and others to open and operate the foodbank, which helped the organization minimize its own investment. And it redeployed team members who were freed up when Instituto streamlined its student support functions as a result of the program strategy map process. The new foodbank has ended up meeting a critical need. "We're getting 1,500 cars showing every time we do it," says Ayala-Bermejo.

* * *

A program strategy map can help a nonprofit's leadership team approach decisions more clearly, understanding not only which programs contribute toward both social impact and financial sustainability, but also how they compare to one another. It is a tool for decision-making—both about the full mix of programs, and about new funding challenges or funding opportunities.

It is also a tool for communicating—to staff, board, funders, and constituents—how those decisions are being made. Instituto’s leadership team has taken to sharing a "before and after" version of its program strategy map with its board and other audiences. Says Chief Quality Officer Ian Sharping, "It's nice to see program data in a spreadsheet, but if you can distill it down to something like our program map, it can show people right away: here's what we're doing, here's what we've done, and here's how we've improved."

The authors would like to thank Senior Editorial Director Larry Yu for his support in this work.

Download the Guide to Using A Program Strategy Map

If you'd rather not share your information, you can download a the guide by clicking here and a copy of the template by clicking here.