More on Impact Investing by Sector

Explore best practices, themes, and trends across several sectors in this impact investing by sector series.Read More>>

Impact investors have been pushing forward. They’ve put more funding into the energy sector than any other; one sample of investors more than doubled its annual investment over the past five years—from $9 billion in 2015 to $19 billion in 2019. Those amounts are miniscule compared with the capital it will take to transform the sector: the IEA hopes for $4 trillion per year in clean energy investment by 2030. But impact investors play an important role in developing new technologies and catalyzing further investment. They’ve homed in on strategies where their capital can provide a lot of leverage in the coming energy sector transformation, and they think more broadly about impact than just emissions.

What impact investors think about when they think about energy

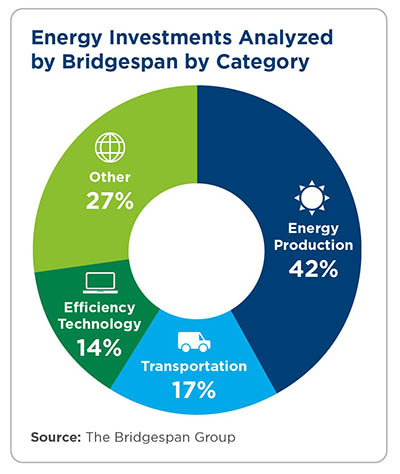

Over the past several years, Bridgespan has worked with a number of impact investors to analyze over 70 potential investments in the energy sector. These investors span the globe and fund companies at different stages. For a lot of investors, the main goal is to mobilize as much capital as they can to abate carbon emissions and avert the worst impacts of climate change. Their focus tends to be in three main categories: energy production (solar, power utilities, waste to energy, wind), transportation (electric vehicles, bicycle and car sharing), and energy efficiency technologies.

For a lot of investors, the main goal is to mobilize as much capital as they can to abate carbon emissions and avert the worst impacts of climate change. Their focus tends to be in three main categories: energy production (solar, power utilities, waste to energy, wind), transportation (electric vehicles, bicycle and car sharing), and energy efficiency technologies.The investors we work with don’t lack for opportunities to invest. Rather, they think seriously about making the most impact they can. They wish to avoid tying up a lot of capital in something that in the end could have little impact on climate change.

Thus, some are attracted to investments that may lack glamor but offer a clear path to efficiently producing energy from renewable sources. These investors seek firm estimates of emissions reductions. Consider Ecoppia, an Israeli company whose little robots that clean solar panels powered its initial public offering earlier this year. The robots, alas, aren’t funny or adorable like C3PO or WALL-E (although company execs might differ). Rather, the practical machines allow solar installations to maintain peak performance with low costs and minimal human intervention. They don’t require water, and they recharge their own batteries with built-in solar panels. Since clean solar panels can produce 35 percent more power than dirty ones, and the solar sector is projected to grow by 20.5 percent per year through 2026, such a technology could have a significant emissions impact.

Other investors look for more of a moonshot—investments that could have a profound impact on climate change. They are willing to accept a lot of risk to invest in areas such as carbon capture and sequestration, direct air capture, fusion reactors, or hydrogen-powered aircraft. Approaches such as these face obstacles and uncertainties along a long and winding path to large-scale impact. But they have game-changing potential for a net-zero world.

Beyond emissions

Impact investors also are keenly aware that the immediate appeal of a technology could mask other potential emissions. Electric cars reduce fossil fuel emissions, right? Yes, in most cases. But a 2020 study in Nature Sustainability finds a few exceptions—in such countries as India, Poland, and Bulgaria, where electric vehicles largely rely on electricity generated from coal-fired plants to recharge.There are also non-emissions impacts that technologies may leave in their wake. Consider electric scooter sharing systems—of which you may already have an opinion if you live in a city whose sidewalks abound with the little vehicles (or in a city whose policymakers have taken action against them). There are real safety issues, along with the annoyance of seeing discarded scooters strewn on sidewalks and in parks. On the other hand, if scooters truly catch on and dedicated rights-of-way or other strategies can address safety issues, they could substantially reduce the role of cars in urban areas and provide a last-mile solution that encourages public transit.

Electric scooter sharing systems illustrate the conflict between emissions impacts and other kinds of social impacts. But other energy investments may also have significant—and less obvious—non-energy impacts. For example, supply chains can come with red flags—such as allegations of forced labor in solar panel production or environmental degradation from mining rare earth minerals crucial for battery technologies—that investors need to understand.

On the other hand, when you look beyond emissions, other good reasons to invest could emerge. For example, SmartWires has developed a tool that enables electric grid operators to direct power to transmission lines that have extra capacity at any given time. This has clear emissions and resilience benefits (fewer outages, easier to bring renewables onto the grid). But there is another bonus under the surface: by allowing current power lines to be used more efficiently, fewer new lines need to be built, resulting in less need to use eminent domain and less disruption to communities. This matters a lot to a net-zero future in which the power grid will need to expand in order to charge our cars and heat our homes.

Most energy sector impact investors share a deep concern about climate change and a strong commitment to doing something about it. But their tolerance for coincident financial and impact risks—particularly non-emissions related impact—can vary quite a bit. Investors would be well-served to deeply understand the full impact of their investments and how those impacts reflect their values and goals. Because the coming transformation of the energy sector will be so dramatic that the values embedded in our investments will be deeply felt across society for decades to come.

Stephanie Kater is a partner at The Bridgespan Group, based in Boston. Erica Kelly and Sam Whittemore are both managers at Bridgespan, based in San Francisco and Boston, respectively.