Overview

Rampant wars, conflict, and persecution are driving the world’s displaced population to record high numbers. According to UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, by the end of 2017, nearly 70 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced—more than the entire population of the United Kingdom. More than a third of displaced persons have become refugees, seeking safety across international borders.1

Governments, aid agencies, and NGOs have long provided humanitarian aid for refugees, addressing immediate needs such as food, water, and shelter. However, the duration of displacement is lengthening for many. In some cases, there is a desire on the part of host countries to repatriate refugees, yet it can be a long and controversial process. The need for sustainable, long-term solutions that mitigate the negative impacts of forcible displacement, uplift refugees, and support host communities is therefore becoming more acute.

Download a PDF of the Full Report

Indeed, the development community is increasingly working to empower refugees as agents of their own lives and economic contributors—from providing skills training to offering employment to enabling access to financial products and services.2 Private sector actors are inherently well-positioned to enhance and scale these efforts, given their strategic capabilities and business models.

Multinational corporations like Mastercard, regional and national businesses such as Equity Bank and PowerGen,social enterprises like NaTakallam and Sanivation, and a range of others across industries, are demonstrating the potential roles of the private sector in supporting refugees and host communities.

Promising momentum

An increasing number of private sector actors are responding to this need and opportunity. In November 2017, the International Finance Corporation partnered with The Bridgespan Group to research these early efforts—aiming both to understand the nature of private sector engagement with refugees and host communities and to derive lessons that could inform future efforts. Across Africa and the Middle East, we identified a nascent yet burgeoning landscape of more than 170 initiatives. Most are early-stage, with promising indicators but still limited evidence of impact on refugees’ lives. The research pointed to a set of common pathways of private sector engagement beyond funding humanitarian assistance:

- Sharing capabilities—such as technology or technical expertise – to provide access to humanitarian assistance, education, or financial services

- Extending services by adapting current business models to sell goods/services to refugees

- Enabling employment by providing job training and/or entrepreneurship support to refugees

- Integrating into value chains by hiring refugees directly and/or working with smaller enterprises that hire refugees through sourcing or subcontracting work

- Building a business through the selling of goods and services tailored to refugee populations

The research also surfaced several barriers to growth and scale—such as insufficient tools and information to engage refugees and inadequate coordination across stakeholders—as well as opportunities to address these obstacles.

Just a year later, private sector activity in the refugee space has moved forward rapidly, and raised its profile. During the 2018 United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) sessions in New York, Business Fights Poverty and Innovest Advisory highlighted key sectoral areas of focus for refugee-inclusive business and investment. Also in 2018, the Tent Partnership for Refugees and the Center for Global Development published research and policy recommendations on helping refugees realize their economic potential and improve their well-being and self-reliance through formal labor market access. Further, the Refugee Investment Network, formed at SOCAP18, laid out a framework for defining, qualifying, and targeting refugee investments.

Understanding the “how” of successful engagement

These and other efforts have helped private sector actors understand why they should engage and which approaches hold promise. What still remains less clear is the “how”: how to identify the best pathways for engagement, how to leverage their existing capabilities and assets, how to find and work with the right partners, how to learn from others, and, perhaps most importantly, how to attain impact at scale.

The current study seeks to complement existing efforts and further build knowledge around private sector engagement. We explore the critical questions of “how” in three ways:

Through a landscape of current and projected private sector activity

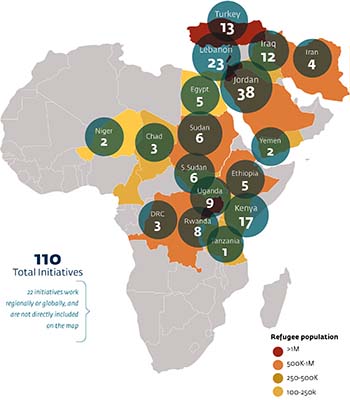

Initiatives by Geography (click the image to enlarge)

Of the 173 private sector initiatives identified, we deepened our research on 110, documenting their approaches, geographic focus, and key partnerships, as well as their reach and investment sizes where such data was available. We found a nascent but growing landscape of initiatives across the Middle East and Africa—most in their early stages, with over half launched within the past three years. The initiatives represent a diverse set of actors, from multinational corporations and their foundations, to regional and national businesses, to start-ups and social enterprises—all across a wide array of industries.

Visibility into this landscape can help inform and inspire future efforts, encourage greater sharing of learnings, and help private sector actors identify potential partners. A survey we conducted also provided insights into actors’ motivations and the barriers they face, highlighting opportunities for other stakeholders to facilitate private sector activity.

Through research of critical enablers of impact and scale

Across our research, as well as in recent discussion forums such as UNGA, stakeholders consistently identified three factors as critical for impact and scale:

- Flexible financing. A growing funding pool is available to support private sector initiatives: our research alone captured approximately $400 million in private investments deployed across 50 initiatives from 2009 to today. However, our research underscores a need to explore beyond how capital is currently sourced, structured, and matched to opportunities for engaging with refugees and host communities. Venture capital-like approaches to funding, with smaller, more flexible, and need-based investments—even within the existing pool of capital—can better enable testing and scaling for the early-stage, innovative, yet unproven initiatives that comprise much of the landscape and pipeline of work with refugees. This flexible financing is particularly important for smaller businesses, start-ups, and social enterprises that rely heavily on financing.

- Cross-sector partnerships. Given its scope and multifaceted nature, addressing refugee needs requires collaboration across the government, humanitarian, NGO, private, and development finance sectors. Many private sector actors recognize this: over 80 percent of our survey respondents cited the presence of potential partners or collaborators as the second most important factor in their engagement (just after positive impact). Yet, they are often unclear on how to create effective partnerships, given the range of underlying challenges. Our research illuminated a set of emerging principles based on successful examples of collaborations: these partnerships ideally start from a common understanding of a specific problem or need, build on the existing assets and capabilities of different partners, and prioritize communication and learning.

- Investment information. Assessing the potential of any private sector opportunity or investment requires a strong knowledge base. This is particularly true for those looking to engage with refugees and host communities. Yet information is not readily available: 60 percent of our survey respondents cited the lack of relevant data and information as a barrier to investment—second only to policy and regulatory constraints. Increasing the information flow on refugee qualifications, needs and preferences, local context, and existing efforts can ensure informed decisions by all private sector actors—especially those without the resources or connections to access such information themselves. By thinking creatively and collectively, the sector can harvest existing knowledge and identify cost-effective ways to gather and share missing information.

Through case studies on the pathways for private sector engagement

We include five case studies, each illustrating how a specific private sector actor explored, evaluated, and approached one of the five pathways. While it may be too early to assess the impact of these efforts, the journeys themselves show how private sector actors can use their assets and capabilities to engage with refugees and host communities—and how other stakeholders can support these efforts.

Sharing capabilities. IrisGuard’s iris recognition technology has streamlined the process of registering and delivering services to refugees in Jordan and beyond. Refugees no longer have to wait at distribution points, are less susceptible to theft and corruption, and have more agency in how they receive assistance.

Extending services. For Equity Bank, which has made banking available to low-income families in East Africa for more than 30 years, reaching out to refugee groups is a natural extension of its financial inclusion work. Equity Bank now provides banking products and services to thousands of refugees in Northern Kenya and is looking to expand.

Enabling employment. Luminus Education is Jordan’s first private institute to provide employment training for refugee youth. Seventy to 80 percent of Luminus’s refugee students find employment—and in some sectors, like hospitality, all of them do.

Integrating into value chains. Sanivation is using an innovative approach to bring more hygienic sanitation solutions and cleaner fuel alternatives to refugee communities in Kenya, while also providing a range of employment opportunities, from manufacturing to sales.

Building a business. Inyenyeri’s innovative cooking system is addressing cooking needs, household air pollution, and fuel efficiency issues in refugee homes in Rwanda. This affordable, market-based solution aims to reach 3,500 households in Kigeme Camp and start expanding into several other camps in 2019.

Private sector actors recognize the refugee crisis is not going away. A full 60 percent of surveyed organizations expect to deepen their engagement in the coming years. These actors share a generally positive outlook and a growing confidence that they can engage in valuable and sustainable ways. Through the five pathways above, they are already using their capabilities to create impact.

With the right enablers—more flexible financing, effective cross-sector partnerships, and accessible information—in place, the impact and scale of private sector efforts can deepen, improving the lives of refugees and host communities around the globe.

Research Methodology

Research period: From August to December 2018

- Identified 173 initiatives, and documented 110 of them in detail, which have:

- At least one driving private sector actor*

- Operations in low- and middle-income countries in Africa and the Middle East close to the points of crisis

- Developed five in-depth case studies

- Surveyed 58 private sector actors on engagement and perspectives

- Conducted 35 interviews with private sector actors, funders, humanitarian organizations, and intermediaries

*Includes private foundations funded by multinational companies

Note: Given the volume of programming aimed at refugees and the study limitations, initiatives identified and profiles in this study are intended to be illustrative, rather than an exhaustive representation of private sector engagement. In particular, the study may not capture efforts of local small and medium enterprises, social enterprises, small refugee-owned businesses, private universities, and informal sector activity.