Executive Summary

Much of the research on the fading “American Dream”—the expectation that children will grow up to earn more than their parents—has focused on the country’s urban areas. However, as the nation’s cultural, economic, and political divides have deepened, there has been accelerating interest in understanding how the 60 million people who live in rural America are confronting the challenges that come with climbing the income ladder.

Eye-opening data have allowed researchers led by the economist Raj Chetty to map out the geography of economic opportunity in rural America, revealing large swathes of the country where children—often those of color—have been left behind. Researchers have identified characteristics that correlate with social mobility—that is, the extent to which people ascend or descend the income ladder—including income inequality, residential segregation, and quality of education.

However, a close-up view of what is happening on the ground—the dynamics, mindsets, and activities within individual communities that support upward mobility—is harder to find. What does social mobility look like in those rural communities where many young people grow up to achieve a higher standard of living? And what are the local factors that support upward mobility in those communities—factors that other rural communities might build on?

Researchers and journalists have documented the challenges confronting the nation’s rural communities—dwindling populations, few employment opportunities, the opioid crisis, and a lack of public investment. However, we also know there are many rural communities that are surmounting these obstacles and helping their young people build a brighter future. National 4-H Council collaborated with The Bridgespan Group to more deeply understand the places in rural America where upward mobility is thriving. We set out to learn from the young people as well as the adults in those communities, in hopes that their insights and experiences might prove useful for other rural communities, as they figure their own way forward.

Working from the Chetty group’s data, we identified 133 rural counties that rank in the top 10 percent of all rural counties for youth economic advancement. To get a ground-level view, we homed in on a subset of counties within the top 10 percent, using characteristics that correlate with upward mobility—such as teen birth rates and high school graduation rates—to guide us. We also used demographic data to seek out counties with some diversity in terms of population size, adjacency to metropolitan areas, racial makeup, and predominant industries.

We followed all of these data, which took us to 19 communities in four regions—the Texas Panhandle (where there are substantial Hispanic populations), as well as Minnesota, North Dakota, and Nebraska (all of which have American Indian populations). Supported by the Cooperative Extension System of our nation’s land-grant universities, we conducted over 200 in-person interviews with public, private, and nonprofit community leaders, including approximately 100 interviews with focus groups comprised of middle and high school students. To discern how these communities increase the odds that their young people will climb the income ladder, we surfaced insights from youth voices. The young people we met with stand at the cusp of their career journeys and are about to confront social mobility’s challenges. Their personal experiences and critical perspectives inform much of what we learned.

This field report details what we found. It offers a firsthand account of economic mobility in rural America, reflecting what we saw as well as what we heard from community leaders and young people themselves.

Six factors that seem to support young people's economic advancement

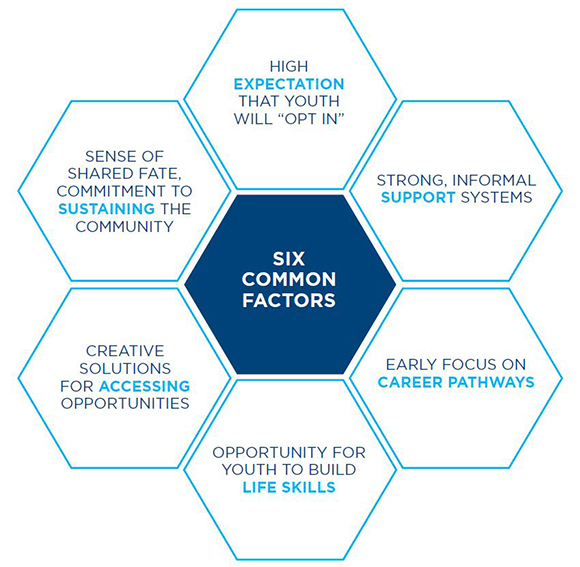

Rural America is not a monolith. Each community we visited had its own unique story. Still, we observed six common factors that appear to be pervasive and to support young people as they advance. In many ways, each factor is a facet of social capital—the connections and shared values that help groups of people build trust and work toward a common goal. The six factors:

- A high expectation that youth will “opt in” and work hard to acquire the skills to build a better future; a low tolerance for opting out. Many of the communities we visited infuse their young people with a sense of possibility—that if they set high goals, they can build a good life. As a result, there are both the expectation and the pathways for young people to “opt in” and participate in skill-building activities that might help them advance. Opting out is far less of an acceptable alternative.

- Strong, informal support systems, with neighbors helping neighbors. Aside from churches, these communities have few formal supports, such as direct service nonprofits and institutional funders. However, for young people who choose to opt in, there is often a strong social fabric to help them. These communities’ high expectations are grounded in durable, informal support systems and celebrations of youth achievement.

- An early focus on career pathways. When considering their future careers, young people exuded a strong sense of direction. Education is not an abstraction, but a foundation for building careers. In some communities, efforts to help children build in-demand skills begin in grammar school.

- A wealth of opportunities for youth to build life skills, regardless of the community’s size. All of the towns we visited, which range from populations of 600 to 20,000 people, are small enough to ensure that every young person has an array of options to build skills. Although they are often remote, these communities provide enough access points for kids to engage.

- Many potential challenges to accessing opportunities, but creative solutions for overcoming them. These communities do not just generate youth development opportunities. Residents collaborate so that as many young people as possible can seize on those opportunities, despite multiple potential barriers—financial, cultural, logistical, or simply a lack of awareness.

- A sense of shared fate and a deep commitment to sustaining the community. People in these small communities still recall existential threats from the past, such as the 1980s farm crisis and the oil industry’s busts, whose aftershocks remain. Against that backdrop, residents spoke of how their individual well-being is deeply entwined with their neighbors’ well-being—that their future depends on taking responsibility for sustaining their communities. In some cases, young people themselves are leading efforts to weather challenges through peer-to-peer and family-to-family support.

These six factors were culled from a small set of communities. To begin to gain a broader perspective, we field tested our insights with a handful of community leaders in six additional counties. They are located outside the country’s mid-section, have household incomes lower than the rural median, and in some cases, have substantial Black American populations. Each of those counties has its own assets as well as challenges, including histories of racial oppression and financial struggles that span generations. Nevertheless, as we show in the report, many of the six factors that support upward mobility still resonated. Each of the counties with more modest outcomes have geographic or cultural pockets where all six factors exist, to varying degrees.

While these factors may offer helpful guidance to other communities, no single approach can put young people on an upwardly mobile trajectory. However, based on the common elements we observed, there are six questions that rural communities and national stakeholders might ask, to inform future action at the local level:

- Does our community expect all our young people to participate and stay engaged?

- What support systems are we providing to our youth, and which are most needed?

- Are we imbuing our young people with a sense of possibility and helping them plan accordingly toward a better life?

- Are we providing a wide array of opportunities for youth to build life skills?

- What actions are we taking to extend access to resources and opportunities to all our people, regardless of their income, race, religion, or location?

- What steps are we taking to build the “demand side” of the economic opportunity equation—are we making our community a place where young people want to remain or return to if they leave?

In answering these questions, other communities can take stock of their assets and deficits. Armed with a clearer line of sight, they can map out ways to improve economic opportunities for their young people and target resources—both homegrown and external—to support them.

Our site visits, while meaningful and informative, touched less than 1 percent of the country’s rural counties. However, we were struck by the common themes that surfaced across all of them. Our hope is that the research, stories, and insights that we detail in this report will help enable the adult and youth leaders of rural communities, as the experts in their own places, to work towards a future where every young person has an equal opportunity to build a better economic life.