Julius Rosenwald is one of our philanthropic heroes. In the early 1910s, having already made business history by transforming Sears, Roebuck & Co. into the Amazon of its day, he set out on an even more audacious mission: to remedy the huge gap in elementary and secondary education for African Americans. In partnership with Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald sparked the creation of the Rosenwald Schools—a term used informally to describe a loose network of nearly 5,000 schools established to educate African American children across the Southern part of the United States. He contributed start-up funding for many of the schools, and, in a groundbreaking move, succeeded in drawing in money from state and county governments.

The effect of Rosenwald’s approximately $70 million (in today’s dollars) big bet was transformative. By 1932, Rosenwald Schools educated more than 35 percent of all African American children in the South. The gap between the region’s races in “years of school completed” shrunk from three years in 1910 to half a year in 1940, with Rosenwald Schools judged responsible for 40 percent of these gains.1 Dozens of African American leaders who would later remake America were educated in Rosenwald Schools, including the late poet Maya Angelou, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson, and the long-serving civil rights leader and Georgia Rep. John Lewis.

Big bets on social change, like the one Rosenwald made, are relatively rare—despite the great desire of most major donors to advance such causes.2 That rarity is heart-wrenching, given that big bets can have extraordinary impact. They can radically change the organizations or social movements they support, creating leaps in their recipients’ abilities or long-term ambitions. Mind you, it’s not a quick process. The biggest bets generally come out of years of work and build on multiple smaller grants.

Our research has shown that a median of four smaller grants precede a big bet (with the big bet being 10 times the size of the previous grant), as the donors and recipients build relationships and trust, and gain knowledge of what’s required to get results. And those big bets nest within a broader arc of social change—one that’s more appropriately measured in decades than in years. But ultimately, it takes a lot to do a lot. Indeed, historically, big bets have been a critical input to many of the nonprofit sector’s greatest success stories.

When philanthropists—and those who help them—think about making big bets, it’s natural to focus mainly on what they are trying to achieve—in Rosenwald’s case, dramatically improving the education and life prospects of African Americans in the South. But the real barrier, the less examined piece of the big-bet puzzle, is how to deploy their resources. The “how” is indeed where Rosenwald truly excelled: building a new field of endeavor, creating standards (such as school building design), establishing a durable funding model, partnering with an esteemed community leader, and propelling it all with an explicit “giving while living”3 philosophy. His work foreshadowed what his audacious philanthropic successors are doing (or trying to do) to change the world today.

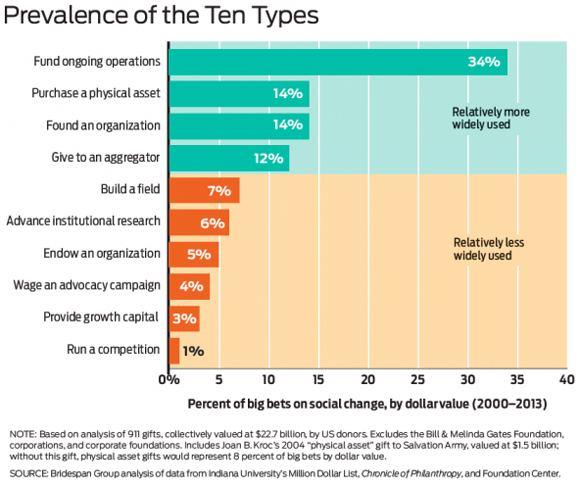

In this article, based on our research of 14 years of big bets by US donors, we describe the various “hows” donors are using—10 distinct ways to place a big bet on social change. They include building a field (as Rosenwald did with public education for African Americans), waging an advocacy campaign, founding an organization, and seven more. In a sense, these 10 types are tools in the toolbox of big betting.

We undertook this research in part because we suspected that donors wanting to make a big bet have more tools than they may realize—and, indeed, they do. In fact, the big bet types that are most rare drive many of the sector’s most important success stories. We’re hopeful that deepening understanding of them can help donors achieve their philanthropic aspirations. Whether it’s economic mobility, global humanitarian crises, or environmental sustainability, society faces enormous challenges—and also incredible opportunities for philanthropists to bet big and, in turn, have a far bigger impact.

The “Right” Type of Big Bet

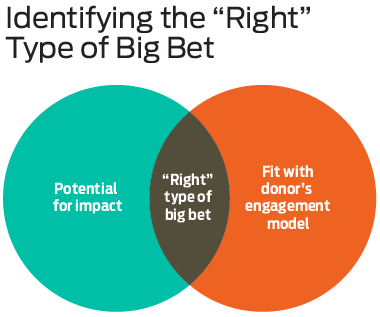

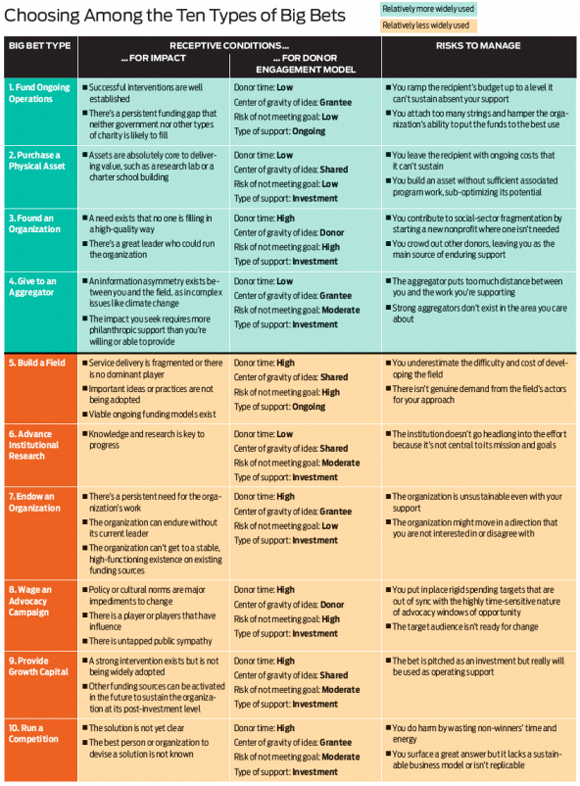

Just as in the world of business, in philanthropy some approaches are simply much more promising than others to achieve a particular goal—in this case, impact. There may be a few types of big bets that could effectively address a given problem, and others that would not. And, some types are a much better fit for a donor’s preferred engagement model. While donors tend to be fairly expansive in the societal issues they’re eager to address, their beliefs about how change takes place are often more focused and specific.

For example, some believe that government is the most important lever for lasting change, while others are generally skeptical that government can be influenced. An investor may want to provide growth capital to a promising nonprofit, while a corporate founder may be more inclined to start a new nonprofit initiative. There are also real differences in the time, staff, and risk appetite they bring to their philanthropy. For a successful big bet to occur, it must be both a promising way to address a problem and a good match with the donor’s engagement model.

Consider Herb and Marion Sandler’s efforts to improve the quality of investigative journalism in the United States. It was 2007, and the business model of traditional newspapers was collapsing. The Internet offered new publishing possibilities, but a dominant player had yet to emerge. Providing growth capital to the major newspapers probably would not have been sufficient to reverse the deep-rooted decline. But other approaches were more viable, such as subsidizing investigative journalism at an existing journal or hosting a competition to surface new journalism models. Yet the Sandlers decided to take a different course, founding ProPublica, which they describe as “an independent nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism in the public interest.”

As co-CEOs of Golden West Financial, the Sandlers had built the company into one of the most successful and admired financial institutions in the United States. They were comfortable operating organizations and hiring leaders. They had also sold the company the year before and had the time to be hands-on in their philanthropic work. Launching ProPublica was a good match not only for the problems facing journalism, but also for the Sandlers’ business experience and for the ways they were able invest their time and talents.

The good news is that there are a number of ways donors can deploy their resources to make a big difference. Below are 10 distinct and significant ways to place a big bet on social change. The list is not exhaustive—but almost every big bet on social change in a sample of more than 900 gifts of $10 million or more in our 2000-2013 database falls into one of these categories. Since some fall into more than one category, we tried to judge which single category best described the form and purpose of the gift. We present the 10 types in order of their decreasing prevalence.

1. Fund Ongoing Operations

Perhaps unsurprisingly, funding ongoing operations is by far the most common type of big bet on social change—accounting for about one third of the gift dollars in our database. Providing revenue for ongoing work is a way to support organizations that will not (and should not) ever be able to thrive without philanthropy. Fortunately, these gifts are typically easier to make and involve less risk than some of the other categories discussed here. They may be hardly “bets” at all.

Sometimes, a steady stream of such large gifts is the main revenue source for an organization. We see this, for instance, with advocacy groups like PolicyLink, which advances equity in public policy. These nonprofits don’t have other natural major backers (like government, which may be the target of the advocacy). And their budgets tend to be modest enough that they can survive on philanthropy alone (versus needing a readily-scalable funding source). At most large organizations, by contrast, philanthropy is rarely a dominant revenue source—though it can play a critical gap-filling role. Consider charter schools, for example. Ultimately, the great majority of funding for these schools, just like district schools, comes from government. But government per-student funding rates don’t always fully cover charter school costs. Facilities financing, small class sizes, extensive teacher training—elements that are critical to achieving the impact that the best charter schools are striving for—often cost more than government provides, and philanthropy closes the gap.

Because funding ongoing operations may seem plain vanilla, donors can be tempted to impose restrictions on grantees that specify what their money is buying. Yet attaching strings can hamper a nonprofit’s ability to put the funds to their best use. It’s generally preferable to pick an organization you believe in so you can give with minimal restrictions. There’s also the concern that a big bet might ramp the organization’s budget up to a level it can’t sustain without your ongoing support. Here, strategies can include bringing in co-funders to moderate the risk of a future funding shortfall, or—if you are confident it should exist in perpetuity—endowing the organization.

2. Purchase a Physical Asset

For some kinds of social change efforts, assets like land or buildings can be important. Community health centers, charter schools, conservation efforts—all may require significant one-time investments in physical assets. These gifts typically have the advantage of being relatively straightforward to give, with fairly certain and clear results—the building is built, the land is protected. Consider the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund’s $15 million gift to the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy in 2007. The funds went to establish trail networks and make other enhancements to the Presidio—a 1,491-acre national park in San Francisco—in line with the Haas, Jr. Fund’s priority of bringing outdoor experiences to youth, families, and underserved communities. Robert D. Haas, a fund trustee, emphasized at the time that the gift was “to help ensure the Presidio will be a place that is used and enjoyed by the entire community.” Today, the Presidio attracts park-goers from all over the San Francisco Bay area, and its camping programs introduce underserved youth to nature and the outdoors.

Physical assets often bring substantial ongoing operating costs, and a gift to buy one might risk burdening the recipient with expenses—so that it ends up rich in physical assets but poor in financial health. The late Joan Kroc addressed this challenge when she designed a $1.5 billion gift to the Salvation Army for new community centers. She stipulated that half the money go to build the community centers and the other half to supplement local fundraising for their operating costs. In other cases—such as health centers (which generate income)—the nonprofit’s underlying funding model may be sufficient to fund ongoing operations.

3. Found an Organization

Sometimes a need is clear, but there isn’t an existing organization with strong potential to address it. The Sandlers, for example, worried that the economic struggles of print media were undermining the ability of investigative journalism to expose and combat corruption. In newsrooms across the country, budgets were being slashed, reporters laid off, and investigative journalism increasingly viewed as an unaffordable luxury. “We searched for a way to put a spotlight on abuses of the public trust, and potentially stop them,” explained Marion Sandler, about their decision to found ProPublica.

The Sandlers made an initial commitment of $10 million a year for three years to what was not only a new organization but an unusual nonprofit model of journalism. Led by Paul Steiger, former managing editor of The Wall Street Journal, ProPublica has gone on to break dozens of important stories, often in conjunction with mainstream newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post, and has thereby distinguished itself and strengthened the field of investigative journalism. This April it received its fourth Pulitzer Prize, shared with the New York Daily News, for a series on the New York Police Department’s abuse of an obscure law to force hundreds of people, predominantly in minority neighborhoods, from their homes and businesses.

Founding an organization tends to be a major undertaking for a donor—perhaps the most demanding of the 10 types of big bets—making it all the more important to make sure that no other entity that might be “good enough” already exists. Given that fully 14 percent of the big-bet dollars in our database fell in this category, this bet type may very well be one that donors deploy too frequently. There is also the very real threat that donors will be hesitant to invest in another donor’s signature bet, leaving the founding donor as the main source of enduring support. Birthright Israel, a nonprofit that works to ensure the future of the Jewish people by strengthening Jewish identity, Jewish communities, and connection with Israel, managed this risk by recruiting a group of 15 co-founding donors to contribute a million dollars a year for five years.

4. Give to an Aggregator

Intermediaries that aggregate and strategically deploy resources (aggregators)—like the Robin Hood Foundation, Jewish federations, and community foundations across the United States—are frequent recipients of big bets. This approach offers donors several advantages—chief among them leveraging the aggregator’s strategic and grantmaking expertise. Donors, in essence, outsource the process of developing strategies, searching for a worthy recipient, figuring out how to structure the deal, and creating and tracking metrics that will tell them if the gift is making a difference. Aggregation also allows a donor’s big bet to be combined with the donations of others, to make an impact that might not be possible with even one very large gift.

These are exactly the benefits that the David and Lucile Packard Foundation reaped from its big bet on the Energy Foundation, an aggregator that promotes sustainable energy and energy efficiency. The late David Packard had deep interests in both China and environmental work. As co-founder of Hewlett-Packard Corp., he was one of the first US businessmen to develop relationships with China, and in his philanthropy supported a myriad of efforts to conserve and protect the earth’s natural systems. After his death in 1996, the Packard Foundation’s board built on these interests by helping China explore ways to reduce air pollution and become more energy efficient. The Packard Foundation’s initial $25 million commitment to the Energy Foundation between 1999 and 2002, plus substantial ongoing annual support, allowed it to create a Beijing office staffed entirely by Chinese nationals that has made more than 1,500 grants totaling more than $230 million. That work has helped China become the leading global investor in wind, solar, and electric vehicles.

An aggregator can offer efficiency, scale, and even learning and camaraderie, but for some donors it may create too much distance between them and the work they are supporting. While the best aggregators are able to involve donors significantly in their work (for example, by engaging them in strategy development or grantee selection), it may not deliver the same satisfaction as investing directly. In addition, for some particular goals, strong aggregators may not exist—and indeed donors sometimes found new ones to fill the gap.

5. Build a Field

In most areas of social change, no one organization is going to solve a complex problem. Nor is any solution so clear that a single leader or entity can chart the exact path to a full-scale solution. By investing in building a field, a big bettor can focus on a single overarching goal, but encourage and align multiple operators and pathways to achieve that goal. Fields ripe for this sort of investment tend to be ones where viable ongoing funding models exist but service delivery is fragmented, important ideas or practices are not in broad use, and competitive dynamics do not seem to push toward improved outcomes.

This was the case for the impact investing field in 2008, when The Rockefeller Foundation set out (in parallel with seminal efforts by the Omidyar Network and later by others collectively investing billions of dollars into the field) to strengthen it. Rockefeller saw the field’s lack of cohesiveness as a major constraint to its growth and efficacy. The foundation committed to deploying $38 million over the next five years. Its investments included coining the term “impact investing” and developing it into a brand of sorts, creating common standards and measures to help guide the field’s many actors, and scaling intermediary organizations that aggregate investors and connect them with investment opportunities. Perhaps its most defining move was to establish the Global Impact Investing Network as a prominent platform for sharing knowledge throughout the field. These diverse efforts paid off. A 2012 evaluation concluded that The Rockefeller Foundation had been instrumental in propelling the field’s “good progress over the past four years, with [the field’s] leaders coalescing around a common understanding of impact investing, mobilizing significant new pools of private and public capital, and putting in place initial industry infrastructure.”

Compared to some of the other types of big bets, field building can require a much longer time horizon. This means that building a field typically takes not only a lot of money but also a lot of time, and a willingness to stay involved for the mid-course corrections that will almost always be necessary in such a complex effort. But for funders willing and able to engage in this way, the payoff in terms of societal benefit can be huge.

6. Advance Institutional Research

Of all the big bet types on our list, this is the one that comes closest to blurring the line between big bets on social change and what we have termed “institutional giving”—large gifts to support universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions. But we include this category as a way to advance social change for a reason. There are some problems where research to reframe our understanding of the problem or to advance the thinking on how to solve the problem can be the key to creating change in the world.

Such was the case when, in 2011, Silicon Valley investor Robert E. King and his wife Dorothy donated $150 million to Stanford University to create the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies (Seed) aimed at alleviating poverty in developing nations. The need Seed aims to fill is deeper understanding of the challenges faced by entrepreneurs and businesses in developing economies, to inform the design of effective poverty-alleviation interventions. “The relationships the university has in Silicon Valley, the range of expertise it has among its professors—it can’t be replicated,” said Dorothy King at the time. “The university can make our money more fruitful than we could on our own.” In 2015, Seed engaged nine different Stanford departments and schools in 19 research projects, in 19 countries around the globe.

If gaining knowledge is critical to having impact, it makes sense to work with the large institutions that have the most impressive track record of developing that type of knowledge. In fact, funding for such core research drove the Green Revolution between the 1930s and 1960s, saving more than 1 billion people from starving to death. But there is a potential downside to this type of big bet: gifts to institutions with broader mandates run the risk of serving more as incremental dollars than in advancing a particular social change goal that may not be an important part of the institution’s mission and goals. It can be hard to affect the focus of complex entities like universities where funding is fungible and purposes broad. History tells us it can be done, however, when donor and researcher objectives are properly aligned.

7. Endow an Organization

Endowing an organization can powerfully advance its long-term ability to address a critical, persistent need. This is particularly true for organizations with an underlying funding model that doesn’t enable them to be sustainable without philanthropic support. It’s also true for organizations with volatile revenue streams, such as government or philanthropically-funded youth-serving nonprofits. The reliable, unrestricted revenue an endowment throws off can help this type of organization weather policy changes or choppy grant funding. Even if an endowment covers just a small portion of an organization’s budget, it still can help stabilize finances or support work that is hard to raise funds for.

Consider the experience of the social policy research organization MDRC. At first blush, its endowment might appear to be of relatively minor importance, covering fewer than 2 percent of its roughly $100 million annual budget. But “it is the highest leverage funding we have,” says MDRC president Gordon Berlin. “It is our primary source of flexible dollars for disseminating what we learn to inform policy and practice, doing strategic planning, investing in new research methods, and seeding the development of new program ideas—the very things that no one else will pay for.”

A $100 million endowment can translate, fairly conservatively, to a perpetuity flow of $5 million. If it’s hard to find social change nonprofits well suited to rapidly deploying $100 million worth of giving, it may be much easier to find such groups that can effectively use $5 million per year on the causes that philanthropists most prioritize. Many donors are hesitant about endowment gifts to social change organizations. Among their chief concerns are that the organization will end up doing something you wouldn’t want to support, and the belief that you could invest the funds for a higher rate of return than the organization could. But the alternative to an endowment—namely a series of individual grants—comes at a very real cost to the nonprofit. There’s the extra time needed to cultivate ongoing grants, and the risk that annual gifts will cease, constraining the organization’s ability to plan long-term or be ambitious.

8. Wage an Advocacy Campaign

For many of society’s biggest problems, lasting solutions require policy or cultural change. In these cases, waging an advocacy campaign can be the right approach. History tells us that big bets can play a crucial role in such efforts. A number of high profile, successful social movements, such as the rejuvenation of conservatism in the 1970s and 80s, and LGBT rights in the last decade, received big bet funding. More than 70 percent of the social movements we studied received at least one big bet that was critical to success. Consider Lyda Hill’s big bet on the Pew Charitable Trusts to address antibiotic resistance. A long-standing Pew funder, Hill has given the trust more than $35 million to support a variety of issue areas, including antibiotic resistance. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that infections that are resistant to antibiotics (because of their overuse) sicken at least 2 million Americans every year—23,000 terminally. To stem this tide, Pew has worked to end farming practices that regularly give antibiotics to healthy animals, reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in health care, and promote the development of new antibiotics.

In agriculture, for example, Pew’s efforts were key to getting the important stakeholders (public health advocates, consumers, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and animal producers) to work together to develop solutions. Sally O’Brien, senior vice president at Pew, characterizes Hill’s role through it all as, “a constant cheerleader, investor, and driver of this journey in a variety of ways. We have a shared vision for the work, and her support (both financial and non-financial) has been integral to its success.” The effort has helped spur the FDA’s improved management of antibiotic use by animal producers and to prompt the retail food industry—including giants like McDonalds and Tysons—to begin reducing the use of animals that have been fed unnecessary antibiotics. The biggest challenge with this type of big bet is the risk of failure. On many societal issues, particularly those that are culturally or politically charged, it can be very hard to move the needle. The gun control and pro-life movements are cases in point. Money can’t buy change if the opposing groups lack common ground and the political will isn’t there. On the other hand, as the marriage equality movement (also fueled in part by a big bet) demonstrated, early “failures” may be essential to softening the ground for later success. This is especially true when the path to success consists of many small wins—instead of hinging on a singular, major legislative or judicial victory.

9. Provide Growth Capital

In the social sector, “growth capital” is often used quite loosely to mean a lot of money. But when used accurately, the term describes something specific and real: a one-time infusion of capital that is more akin to investment dollars in the business world. The recipient doesn’t fall back down to its original state after the growth capital funds are spent, but rather sustains itself at the new, higher plane.

Consider the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation’s (EMCF) investments in Youth Villages, a national nonprofit that serves youth involved with the foster care, juvenile justice, and mental health systems. Once Youth Villages is established in a state, the great majority of its operational funding comes from government. But the non-recurring and often substantial costs of getting Youth Villages established in the first place can rarely be covered with government funding. That’s been the purpose of the multiple growth-capital big bets EMCF has made on Youth Villages, and also of the $40 million EMCF helped secure from 11 co-investors in 2008 as part of its Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot. In 2015, with Youth Villages ready for another tranche of growth capital, a major new co-investment fund called Blue Meridian Partners, spearheaded by EMCF and 11 other philanthropists, invested an additional $36.1 million (the first part of a potentially larger investment of up to $200 million) so that Youth Villages and its partners could provide high-quality services to nearly all of the 23,000 US youth who age out of foster care annually.

Growth capital isn’t just for expanding an organization’s reach. It can also be used to improve a nonprofit organization’s internal operations. Take IT investments, for example. The Anne Ray Charitable Trust gave more than $30 million between 2012 and 2017 to help The Nature Conservancy (TNC) upgrade its core technology systems. “Competing funding priorities can lead to underinvestment in technology and core infrastructure,” says Mark Tercek, TNC CEO and president. “Anne Ray understood this challenge and made a very generous grant that allowed us to modernize our systems. It was an enormously strategic investment that will pay big conservation dividends for generations to come.”

As successful as these investments have been, not all nonprofits are suitable candidates for growth capital. The strategy only works when the nonprofit develops infrastructure and operations that will still generate increased impact even after the growth capital is spent.

10. Run a Competition

Many philanthropists feel tremendous urgency to solve pressing societal problems—like poverty, disease, and environmental degradation—yet many do not see solutions at hand. A competition offers them the chance to galvanize the best thinkers to find solutions or take bold leaps. It is also among the flashiest strategies in philanthropy.

Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge is one of an increasing number of high-profile philanthropic competitions. More than 750 cities in 47 countries have competed for a chance to win a grand prize of $5 million and four $1 million awards, plus coaching and technical support, to implement their ideas. The prize also gives cities public recognition as leaders in innovation and a chance to participate in a network of municipal innovators. Past grand prize winners include Providence, R.I. (for increasing the number of words that young low-income children hear at home every day) and Barcelona (for using a new digital platform to reduce social isolation among the city’s growing population of elders).

Competitions unleash creative energy, but can also produce great waste—all the effort put in by the “losers.” This puts a real premium on designing competitions so that even those that don’t win move their organizations or fields forward. Bloomberg designed the Mayors Challenge to raise all applicants’ awareness and competency around a set of 21st century skills, such as using data to define problems and prototyping solutions. Bloomberg also provides postcompetition technical assistance to any finalist (including those that do not win one of the five grants) that continues to work on its idea. They’ve seen numerous non-winning ideas move forward or inform the way cities ultimately tackle issues. The challenges of scaling up programs can also limit the ultimate impact of competitions. Even if the winner creates what seems to be a great answer, it may go nowhere if the results aren’t replicable or if it lacks a viable business model. Competitions work best where a new idea or policy really can unlock durable change.

Accelerating Progress

When on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Ala. bus, she became an icon of and inspiration to the Civil Rights movement. At least half a dozen less well known but equally brave activists took similar actions. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund built on their courage to pursue justice in court. Less than one year after Rosa Park’s valiance, the US Supreme Court upheld Browder vs. Gayle, stating that the enforced separation of whites and blacks violates the Constitution of the United States. The story is iconic. Less well known is that the funds that fueled the NAACP’s disciplined legal strategy came from bold philanthropists. Among them was Edith Stern, daughter of the philanthropic hero we cited before, Julius Rosenwald.

Throughout our history, a number of big bets have changed the world. And, while giving generously has become an increasing norm among the wealthiest, making big bets on our toughest problems has not yet become common. Not all donors have a family heritage, like Edith Stern’s, to guide their path. But the more well known the stories and pathways become, the more these rare acts can become normal. We hope that deepening understanding of these 10 ways to bet big on social change will accelerate that process.

William Foster is a partner and head of the consulting practice at The Bridgespan Group. He was previously executive director of the one8 Foundation (formerly the Jacobson Family Foundation).

Gail Perreault is a partner on The Bridgespan Group’s knowledge team. She was previously director of learning and performance management at one8 Foundation.

Elise Tosun is a manager in The Bridgespan Group’s Boston office.

The authors thank Bridgespan colleagues Sam Swartz, Bradley Seeman, Alison Powell, and Chris Addy for their contributions.