(This article originally appeared in "Becoming Big Bettable" published in the Spring 2019 issue of Stanford Social Innovation Review.)

Some thoughtful critics of big-bet philanthropy are concerned that outsize gifts could reinforce society’s existing power dynamics around race and class rather than furthering more equitable outcomes. Bridgespan shares these concerns. As a result, we looked at our big-bet database to research this issue. We found reason for hope and reason for concern—and a call to action.

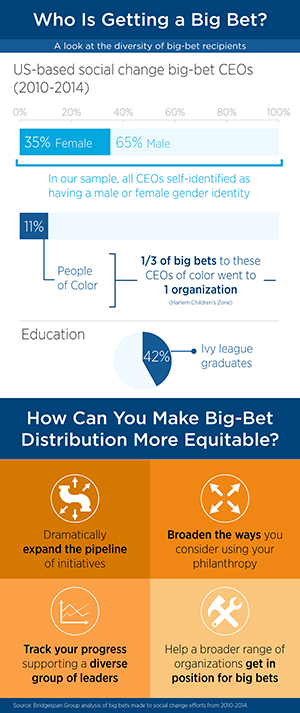

We also found, however, that the leadership of big-bet recipient organizations is not particularly diverse by race or educational background (see "Who Is Getting a Big Bet," right). Of the total number of big bets for social change documented in our database that donors committed between 2010 and 2014, only 11 percent went to organizations or initiatives led by people of color. One organization, the Harlem Children’s Zone, accounted for a third of those bets. These findings parallel studies showing that people of color are underrepresented in chief executive roles across the nonprofit sector, with estimates of their representation ranging from 10 to 20 percent.1 Starting on the hopeful note, a large portion of social change gifts focus on equity, opportunity, and justice causes, some with important effects. Take, for example, several recent big bets that seek to advance the education of America’s undocumented youth, close the racial disparity in breast cancer mortality, reform the US criminal justice system, and advance women’s empowerment globally. Expanding the number of such large and thoughtful gifts would unleash important change.

Although it is difficult to find comparable measures for social class, when we looked in our sample at the college or graduate-school background of leaders whose organizations had received big bets, we found that 42 percent were graduates of Ivy League universities. This is an extraordinary concentration from just eight institutions. The world’s billionaires have also disproportionately attended Ivy League schools, which accounted for five of the top seven of their alma maters.2 While it is good to see so many purpose-driven leaders from these schools focusing on the social sector, it surely speaks to the outsize role of personal networks and shared backgrounds in making the connections and developing the trust to make big bets. These patterns leave enormous opportunities undiscovered and unfunded.

It does not have to be so. Take two examples that demonstrate ways funders have broadened their perspectives. In 2010 Morgan Dixon and Vanessa Garrison, two black women who became friends while in college in Los Angeles, founded GirlTrek, an organization that encourages black women and girls to walk as a practical first step to healthy living, families, and communities. Starting as simply a “radical act of self-care” and taking years to become a nonprofit, GirlTrek now has more than 150,000 walkers and is the largest health movement in the country for black women. Dixon and Garrison secured initial support from Teach for America, won an Echoing Green fellowship, and organized an incredible walk on the National Mall. TED, always researching to find great social innovators, learned about GirlTrek in the New York Times’ column “Fixes” and asked Dixon and Garrison to give a talk that has now been watched by more than one million people. As a result, GirlTrek came to the attention of The Audacious Project (a funders’ collaborative housed at TED), which supported them to plan an expansion into the 50 highest-need communities in the United States and then made a big bet to help fund that expansion.

Or consider Patrick Lawler, who grew up in a white blue-collar family, graduated from Memphis State University, and has spent his entire career working with vulnerable children. He helped turn a failing residential center in Tennessee into Youth Villages, one of the country’s most high-impact nonprofits. Back in 2004, Youth Villages was a remarkable nonprofit success but not on the radar of philanthropists outside of the state. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation found Youth Villages through a disciplined process of secondary research to discover less-known opportunities and has since made multiple big bets on Youth Villages’ work. Today, the organization has grown far beyond Tennessee to help more than 25,000 children, families, and young people annually, with a complete continuum of programs and services across 15 states and 74 locations.

As our data show, there are real disparities in who has access to opportunities. In a companion piece to this article, Cheryl Dorsey refers to “compound bias”—the multiple, overlapping systemic barriers that stand in the way of channeling more big bets to organizations led by people of color. (See “Hacking the Bias in Big Bets”). We know from Bridgespan’s own work that there is a much broader set of initiatives that can change the world than those currently receiving funding.

For philanthropists who want to help close these gaps, we offer four recommendations:

- Dramatically expand the pipeline of the initiatives that you consider. Collaborating with leadership pipelines like Echoing Green, consulting with broader sets of advisors that include individuals from the communities you intend to support, and conducting serious secondary research can help to identify many more possibilities.

- Broaden the range of ways you consider using your philanthropy to create social change. For example, only around 10 percent of social change big bets are focused on building fields and advocating for change, efforts that most directly work to change the fairness of the underlying social systems.

- Track how you are doing on supporting leaders of color and leaders from a range of educational backgrounds. Are you getting out beyond your inner circle? Are those leaders bringing the full range of experiences and perspectives needed to break through on tough problems? If not, consider setting clear goals for the kinds of diversity you are seeking—and measure and manage to them.

- Support promising initiatives to help a broader range of organizations, including those led by leaders of color, get in position to receive big bets. While few nonprofits have big-bet plans sitting in a drawer awaiting funding, many more can develop such investment concepts given appropriate funder support.

For great ideas and greater equity, donors need to look beyond their inner circles and help support a diversity of leaders and initiatives to do their work and to become big bettable.