The number one responsibility of any board—for-profit or nonprofit—is management of the senior executive. Dozens of governance books drive this point home. Yet, when we talk with nonprofit leaders, it's simply not their experience. Nearly half (46 percent) of the 214 CEOs responding to a recent Bridgespan Group survey reported getting little or no help from their boards when first taking on the position. As one executive director puts it, "The board essentially said, 'We're glad you're here. Here are the keys. We're tired.'"

Such comments were not the exception. Overall, survey respondents portrayed nonprofit boards as frequently disengaged or ill-equipped to effectively support their new leaders. "The board assumed I knew what I was doing, and there was effectively no training at all," says one executive director recruited from a for-profit organization. "Having never been an executive director before and having never worked in a nonprofit, I had no idea what I was doing." Anecdotes and data tell the same story: when it comes to managing the senior executive, nonprofit boards underperform.

This chronic shortcoming is understandable given the nature of nonprofit boards. Board members typically are volunteers, and according to BoardSource, the top two criteria for picking them are professional expertise (for example, legal or specific business backgrounds) and ability to represent constituent needs. Experience managing people doesn't make the top seven criteria for selecting board members. Lacking backgrounds in coaching and mentoring, it's not surprising that many boards don't even try. Once the new leader is on the job, boards typically step back from an active role out of sheer fatigue. They are often burned out from a demanding executive search, and eager to hand things off to the new leader and go back to their day jobs.

Why Onboarding Matters So Much

If the root causes of board underperformance are understandable, at no time are they more important to overcome than during the transition to a new leader. A surprising number of nonprofit boards regularly confront this critical leadership juncture. In 2012, BoardSource found that 17 percent of nonprofits either had an executive on the job less than a year or one planning to leave in the coming year. Succession planning and CEO development consistently rise to the top as the most important issues in Bridgespan's organizational leadership surveys.

Setting up the transition for success requires thoughtful investment of the board's time. "Executive transitions call on the board to step up to a higher level of engagement and to lead the organization through a crucial period that will determine its future course," writes Don Tebbe in his book, Chief Executive Transitions: How to Hire and Support a Nonprofit CEO. When a lax onboarding process leaves the new executive struggling to succeed, the organization squanders a crucial learning opportunity and diminishes its effectiveness. Addressing this pitfall has to start long before the new executive arrives. It requires boards to adopt a leadership development mindset that links the board's strategic vision to expectations for the new executive.

Numerous books and articles on leadership transitions exist in the nonprofit and for-profit arenas. Yet for many nonprofit boards, access to know-how is not leading to outcomes. In an effort to translate insight into influence, we surveyed top executives across the United States to confirm where board's involvement in onboarding falls short (214 responded); reviewed the literature; and interviewed 30 experts, board members, and newly hired executives to understand the handful of critical actions that could make the biggest difference. We've boiled down our findings into five recommendations that can boost a board's performance where it counts the most: onboarding and supporting the new CEO.

1. Lay the groundwork for the new leader.

Helping a new leader succeed starts well before that person is hired. The board needs to be clear about where the organization is headed before recruiting begins. "I help my clients do a mini-visioning session before we start looking for a new CEO," says search executive Anthony Tansimore, vice president of leadership impact at Olive Grove. "This helps the board define their goals for the future and what they need to do to get there." Think three to five years down the road about potential growth, restructuring, new programs, or strategies. By working backward from these goals, the board can identify the skills and attributes needed in a new leader and help set expectations with final candidates about what's expected of them and what challenges they might face.

Taking stock of the organization can also help the board identify any tough choices that it might want to address before the new leader takes over. "My board did some cleanup to lay a smoother runway for my arrival," says one new CEO. "They fired a few underperformers from the senior team so I didn't have to be blamed for it."

Boards can also help facilitate a connection between the incoming and outgoing leaders, even before the new executive starts. Zach Bodner, CEO of the Oshman Family Jewish Community Center, says that he had weekly appointments with the interim executive director months before he officially started. "[The interim executive director] made a comprehensive agenda of different topics we needed to cover," recalls Bodner. "From our conversations, I developed a learning plan and an action plan. What was I going to do with my first 30, 60, 90 days? What I was going to say in my first staff meeting?"

2. Collectively set the new leadership agenda.

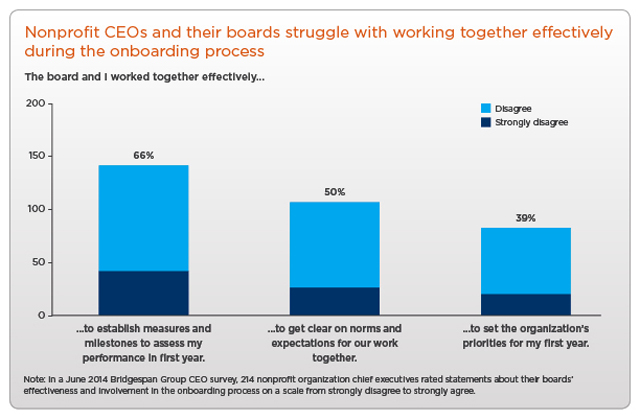

The foundation of the relationship between a board and its executive is a shared understanding of the organization's goals and their roles in a plan to get there—what some call the leadership agenda. Yet our survey showed that 39 percent of respondents disagreed with the statement, "My board was effective in helping me set priorities the first year."

"The board and the incoming CEO must agree on what their accomplishments should be, and in what timeframe," says Tom Adams, author of The Nonprofit Leadership Transition and Development Guide. "If that discussion never takes place, the board and the new leader will likely form clashing assumptions about what is expected and when." When things go wrong between CEOs and their boards, it's often the result of a failure to reach a common understanding of what they are working toward together in the first place.

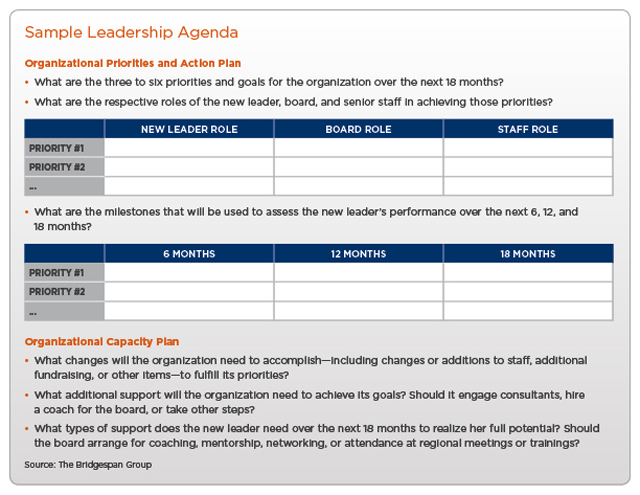

The leadership agenda should clarify the organization's priorities; develop action plans, roles, and milestones for each priority; and identify gaps in organizational ability or capacity to achieve them. Building the leadership agenda should be a dynamic process; it should start with an emerging vision set by the board before the new leader arrives and then get jointly fleshed out with the CEO as that person learns about the organization during the orientation process (see recommendation 4). The template below provides an outline of what a leadership agenda could look like.

3. Get clear on roles.

In addition to setting expectations about the leadership agenda, boards and new CEOs need to get clear about how they are going to work together. This is another arena in which board performance falls short. Our survey showed that 50 percent of executive directors did not clarify with their boards how they would work together in the first few months on the job.

One board chair of an international youth development organization recalled how the new executive director received "no guidance on how to interact with the board," an oversight that created tension and mistrust. "He was slow to respond, which really upset a lot of board members," says the chair.

The more detailed a board can get with their new CEO about expectations, the less likelihood for pitfalls later. Adding a section to the leadership agenda that is explicit about working norms can be a powerful way to ensure that everyone is on the same page. Some questions to consider include:

- How frequently will the CEO and board chair communicate?

- When will board meetings occur? Who will set the agenda?

- What decisions will the board participate in?

- How and when will the CEO's performance be formally evaluated?

- How can the board and new leader share informal two-way feedback throughout the year?

"The relationship of a new leader with the board in the first few weeks is a good predictor of the relationship over time," says Wayne Luke, managing partner of Witt/Kieffer's nonprofit executive search practice. "Not staying in close contact is a recipe for disaster, and building out the leadership agenda is a powerful platform for establishing a collaborative relationship."

Role definition is also an issue with departing leaders, particularly founders or individuals who are retiring. Often they want to stay closely engaged with the organization after they leave. But a leader who sticks around too long can confuse the staff, create divided loyalties, and sow doubt about the competence of the new leader.

It is up to the board to shape an appropriate role for its outgoing executive that supports knowledge transfer, as Bodner experienced, without interfering with the organization's pivot to its next phase of development. Leading up to the new CEO's arrival, the departing leader can help with the transition by preparing the organization for change, setting a positive tone in communications, sharing information, and handing off major relationships and donors. Once the new leader has taken the helm, the board should carefully consider the predecessor's role in the organization, and when in doubt, adopt the philosophy that less is more. "If you must create a role for the predecessor, make sure it's a limited and very tightly defined role—and hold the board accountable for making sure it stays that way," Luke says.

4. Go slow in orientation to go fast on the job.

The first few months on the job are the time for the new leader to listen and learn, forge relationships, and gain a sense of the organization's strengths and weaknesses, challenges, and opportunities. The survey revealed overwhelming dissatisfaction—58 percent—with this element of onboarding.

To ensure that the new CEO has time and space for these activities, the board needs to make orientation a priority. That means the board should keep some day-to-day duties off the new leader's plate at the outset. "Too many leaders are fighting fires from day one, and they miss a critical window to understand and assess the organization and build strong relationships," says Tim Wolfred, author of Managing Executive Transitions: A Guide for Nonprofits. "As a result, they get off to a limping start and could end up playing catch-up for years."

When Amy Saxton started in 2011 as CEO of Summer Search, a national youth development nonprofit, her new boss, Board Chair Ted Williams, understood that his workload was about to increase. During Saxton's first few months, Williams helped her conduct a cross-country listening tour of the organization's sites. "I met with over 100 people in 100 days across all seven of our sites—board members, staff, donors, partners," says Saxton. "By the end of those 100 days, I had a deep sense of where the organization was and a vision for where I wanted to take it. I had built credibility with important stakeholders and a partnership with my board that has served me to this day."

Throughout the process, Williams made himself available to Saxton to answer questions, and offer advice and encouragement. "We talked almost every week," says Saxton. "He was an invaluable partner in helping me learn the organization and become empowered to be its leader." Says Williams: "We made it clear to the senior staff that Amy's job for the first three months was to gather perspective, not to make active management decisions. We were explicit: no key measurement goals in the first few months. We wanted Amy to go out and visit the sites, talk with the directors, and start getting a feel for the organization."

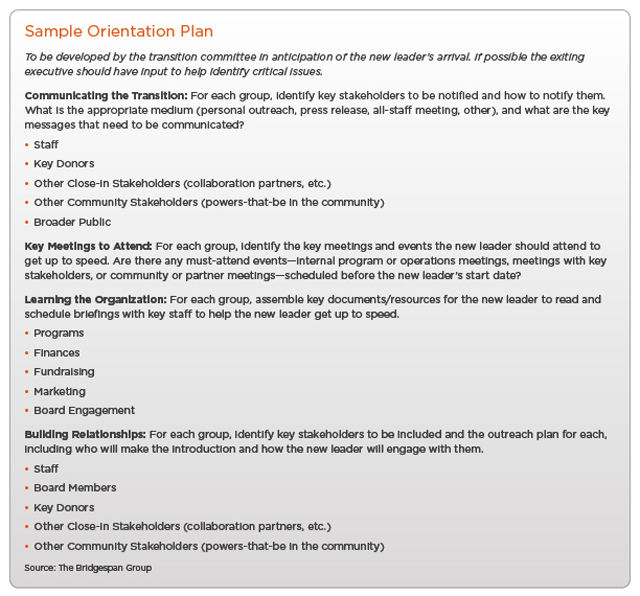

The onboarding process, however, is not just the board chair's responsibility. It's a good idea to set up a transition committee that's an extension of the search committee or a new group of board members plus staff. The committee typically includes the board chair and should work with the new leader to develop an orientation plan for the first 30 to 45 days. Main objectives of this plan should be to get the new leader into the flow of the organization; assemble important documents and schedule briefings on functional and programmatic areas; and introduce the new executive to staff, board members, funders, and other stakeholders. The template below presents a step-by-step guide to this process.

Cynthia Figueroa recalls that in 2011 when she became CEO of Congreso, a multiservice organization serving the Latino community, the board and staff pulled together "two enormous binders" containing all the important legal documents and other critical information about the organization she would need. They also helped her schedule a listening tour of Congreso's sites. "I let staff ask me anything they wanted. ... It became the basis for our plan for the first year."

5. Make performance management routine.

A critical component of the board's role in managing the executive director is to establish clear performance expectations and a cadence for ongoing performance reviews to provide the new leader with the feedback and guidance they need to succeed. Setting expectations proactively—before things go awry—lays the foundation for a healthy and clearly defined relationship between the board and the new executive. Unfortunately, this is where our survey showed the greatest dissatisfaction with board performance. Sixty-six percent of executive directors disagreed with the statement: "The board and I worked effectively together to establish concrete measures and milestones for the board to use to assess my performance in my first year."

The goals and milestones established in the leadership agenda should be a good starting place for setting a performance plan for the CEO. The board and the CEO should set a timeline for checking in on how things are going along the way, perhaps starting with a 90-day informal check-in and then setting an initial formal review at the six month mark.

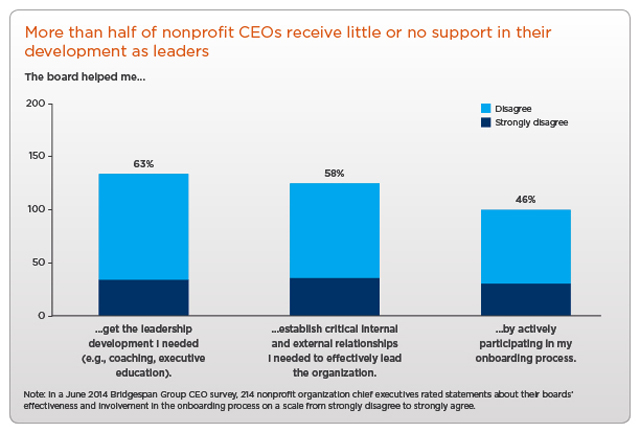

The board should also be proactive about providing support to the executive director. It's easy to assume that a new leader will handle any challenges the role presents. It's also unrealistic. The CEO role can be stressful and isolating, and almost all new leaders can use some help at some point. Most will be hesitant to ask for it for fear of appearing weak. Boards need to be proactive about ensuring that the CEO gets needed support—but most aren't. Sixty-three percent of survey respondents reported that they did not get sufficient development support from their boards.

One powerful way to support a new leader is to provide funding for an executive coach. Respondents to the 2011 CompassPoint "Daring to Lead" survey of about 3,000 nonprofit leaders overwhelmingly cited executive coaching as the most effective professional development investment for senior leaders.

Shortly after Saxton joined Summer Search as CEO, she gratefully accepted a board member's recommendation that she work with an executive coach. "She knew that I needed someone who wasn't associated with the organization to help me think through how to approach situations," says Saxton. "It wasn't a sign of my weakness; it was recognition that all leaders need support, especially when they're taking on a new role."

Coaches aren't just for executive directors, either. Many boards find it extremely helpful to hire a coach to prepare for and navigate the first year of new leadership. "I often provide support to both the CEO and the board," says an executive coach. "Both parties often need an adviser to work through the challenges of a transition, and having that adviser be the same person increases collaboration and reduces the potential for conflicting approaches."

New leaders may also need other professional development to round out their skill sets or build their networks in new fields. Boards should encourage new leaders to identify their development needs and make plans to address them through such activities as executive education, networking with peer organizations, or joining a local CEO group.

When Boards Invest in the CEO, They Invest in Their Mission

Time and energy devoted to executive leadership transitions are a direct investment in advancing an organization's mission. And it's time well spent. "While I spent as much time—or more—on the transition as I did the search, the quality of that time was much better," says Williams, the Summer Search board chair. "Once Amy came on, I was much more energized. It was an exciting time, full of opportunity. I got to focus on why I do this work in the first place." Like Summer Search's, all boards have the capacity to ensure that their organizations hire and support strong leadership. They just have to make it a priority. After all, it's their most important job.