In recent years, the philanthropic world has seen some spirited debates about the best way to “do” philanthropy. Is “strategic philanthropy” the best way to scale impact for the long term? Does “trust-based philanthropy” better honor the knowledge and experience of nonprofit partners? Such questions are worth studying and we expect they’ll advance the social sector in the long run. We’ve dabbled in the discourse ourselves, for example, in “The Trust-Based Philanthropy Conundrum: Toward Donor-Doer Relationships That Drive Impact.”

At the same time, we recognize that many donors are looking for more straightforward guidance that they can put to use tomorrow. When it comes down to brass tacks, they aren’t considering how best to define their philanthropy, whether “strategic” or “trust based.” In reality, they simply want to know how best they can contribute to the work of their nonprofit partners. But what does that really mean for them?

One approach is to conduct due diligence by identifying potential nonprofits that share their goals and reflecting: “What does this organization need in order to achieve its intended impact?” Some of those things will be monetary, but there will be others that are not. A donor with a clear-eyed sense of their assets can then honestly consider if they are in a position to offer that support.

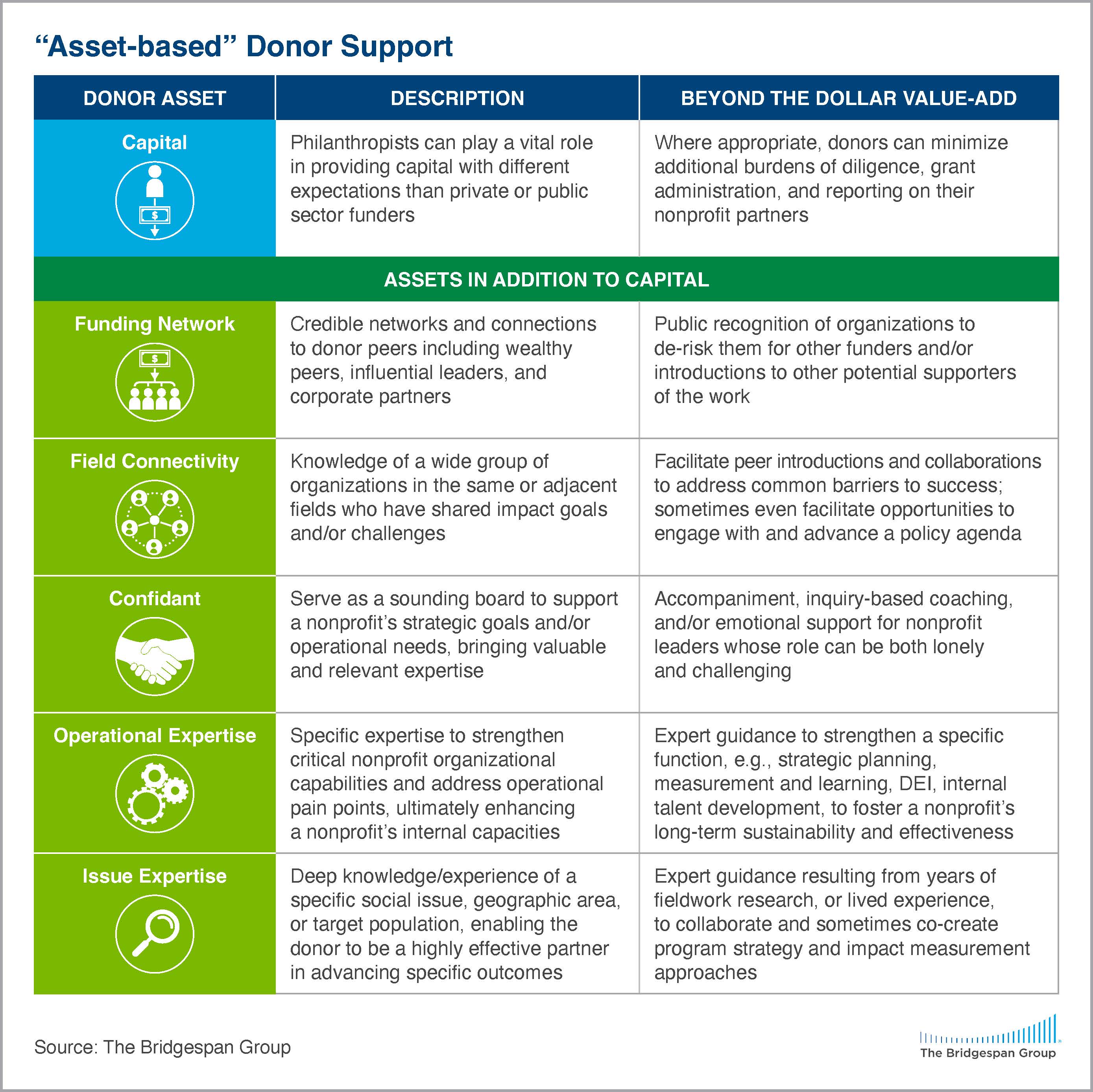

The Assets Funders Can Offer

Reflecting on our personal experiences working with donors and nonprofits, we’ve found that donors’ approaches to giving are often a combination of the change they want to see in the world (their intended impact) and the resources they bring to make it happen (their assets). For this piece, we have chosen to focus on assets. This is because the donors we’ve seen who are self-aware about the assets they bring are more likely to build productive partnerships with nonprofits that realize the impact they both intend.

The behaviors we describe below aren’t meant to box anyone in and our intent isn’t to develop a philanthropic theory. Instead, we offer a starting point for reflection, an exercise that invites donors and their teams (individuals, institutions, and corporate philanthropies) to think through different opportunities related to their circumstances.

Several factors risk getting in the way of donors and doers landing in the most productive partnership. One is, of course, the power dynamic between those with money and those that need money to do their work. This power dynamic can make it difficult for nonprofits to tell a donor when they’ve overstepped or are undermining the work in some way. The ideal is for donors to be proactive in seeking feedback about whether their “beyond the grant” help is actually helping. This can include inviting anonymous feedback through avenues like The Center for Effective Philanthropy’s grantee surveys and other tools.

“Asset-Based” Opportunities for Donors to Add Value

The descriptions below invite donors to review their assets in the context of the ecosystem surrounding their area of focus. Every donor’s approach will evolve over time. As they gain more experience and their assets shift and fields change, they may move from one behavior to another. It is also probable that they will inhabit and exhibit different behaviors at different points on their journeys as experience begets pattern recognition begets insights.

Capital as Asset

Capital provides crucial fuel for nonprofits. Philanthropists can play a vital role in providing grantees with different (sometimes more flexible, innovative, longer-term) expectations than private or public sector funding. While some argue that simply giving money is not enough value added and that capital is one of the less important assets philanthropists bring, nonprofit leaders often tell us otherwise. Some donors do bring other assets, but many do not—and that’s okay. For donors—particularly those new to the work, those who haven’t built in-house expertise, and/or those who have limited time and capacity—finding and funding nonprofits is often the most valuable contribution they can make.

As others have explained, this approach isn’t at odds with being a strategic or results-oriented philanthropist. In fact, it aligns quite well with those goals, particularly when paired with thoughtful nonprofit partner selection. Additionally, given that unrestricted funding can be the hardest to raise, it’s an asset that is even more valuable and important when it is given because of the flexibility it brings.

Funding Network as Asset

Credible networks and connections to donor peers are assets that are often underutilized. In some cases, philanthropists have extraordinary access to wealthy peers, influential leaders, and corporate partners that can be valuable links for their nonprofit partners. This enables donors to serve both as providers of capital and connectors to other potential supporters of the work. The ability to facilitate connections to broader networks can be especially useful when donors simultaneously serve as validators of their nonprofit partners’ work.

Field Connectivity as Asset

Some donors develop a wider view of a field through sustained investment over a long period of time and deliberate efforts to cultivate relationships. With the ability to step back and scan the landscape, they can gain valuable insight into the work of other organizations in related and adjacent fields. This wide-angle perspective illuminates the contours of the system, uncovering gaps, overlaps, and opportunities for collaboration.

Philanthropists who leverage this knowledge to connect nonprofits with one another and with other actors in the system bring the asset of connectivity in pursuit of impact. By understanding the shared goals and capabilities of different organizations, they can facilitate peer introductions and foster collaborations that address common barriers to success. Additionally, some donors may be able to draw on their networks and leverage their reputations to facilitate opportunities for philanthropy to engage with and advance a policy agenda.

Confidant as Asset

Philanthropists with significant leadership experience may offer their time and attention as a sounding board to support a nonprofit’s strategic goals and/or operational needs. While donors can bring valuable and relevant expertise from other sectors, understanding the nuances of the nonprofit sector and respecting the expertise of nonprofit leaders is key in helping nonprofits chart their paths forward. As a sounding board, it’s important for donors to ask thoughtful questions, test ideas, and help nonprofit leaders gain strategic clarity while acknowledging the boundaries of their own knowledge.

In addition to expertise and insights, donors can also provide accompaniment—emotional support to nonprofit leaders whose role can be both lonely and challenging. Along with asking insightful questions, a donor can sometimes simply walk beside a nonprofit leader, validate what they are seeing and feeling, and help sustain the energy needed to do this type of work.

Operational Expertise as Asset

While recognizing fundamental differences between the nonprofit and for-profit sectors, some donors can bring valuable guidance on strengthening critical nonprofit organizational capabilities, such as strategic planning, financial management, measurement and learning, DEI, and internal talent development. This can pay great dividends by shortening the nonprofit leadership team’s learning curve and accelerating progress.

Donors who bring this expertise may be recruited to a nonprofit’s board to effectively assist in addressing common operational pain points to enhance their nonprofit partners’ internal capacities, fostering long-term sustainability and effectiveness. With a belief that in many arenas strong organizational foundations are essential for lasting social impact, they aim to deeply understand a nonprofit’s needs and identify solutions for functional gaps. By strengthening these core areas, they not only support nonprofits in achieving their missions but also help to build their resilience and their ability to adapt and thrive in the face of current and future challenges.

While operational expertise is valuable, nonprofits can have unique operational needs that don’t align with business practices. To reduce the risk of overreach or assumptions that do more harm than good, it’s important for donors to recognize the nuances that make the application of for-profit sector structures, for example, less relevant to their nonprofit partners.

Issue Expertise as Asset

In rare cases, donors invest so deeply in their own learning and/or accumulated on-the-ground experiences—often over many years—that they develop deep expertise of a specific social issue, geographic area, or target population. This creates the opportunity for them to be highly effective partners in advancing specific outcomes. These donors bring both capital and years of fieldwork, research, or lived experience, to collaborate and sometimes even co-create program strategy and impact measurement approaches.

In the extreme, lines between donor and doer can blur, as the donor may have a strong perspective—based on robust knowledge and understanding—about what needs to be done. In such cases, they may go so far as to consider nonprofits as subcontractors for their own strategic objectives. This happens more often than is ideal, but it can make sense from time to time. (Another permutation of this mix of expertise and financial capacity can be found in some operating foundations.)

Conclusion

Being clear about the assets a philanthropist brings to their nonprofit partners can be critical for building a strong, lasting funding relationship that drives meaningful impact. When donors understand and communicate the assets they can offer—whether funding, network connections, or expertise—they contribute to fostering a relationship that enhances, rather than inhibits, the work. This clear-eyed self-awareness allows donors and doers to come together in a way that amplifies each other’s strengths, opening doors to new possibilities and creating a foundation for lasting change. By thoughtfully leveraging their assets, donors can empower their nonprofit partners to achieve shared goals, ultimately leading to a deeper, more sustainable impact.