Executive Summary

Climate change poses severe threats to farmers in India. From disasters such as deadly heat waves and floods to shifts in seasonal patterns, rainfall, and temperatures that stress natural ecosystems, farming is becoming increasingly challenging. The latest assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found multiple studies suggesting that, without adaptation measures, yields of key crops could decline significantly, posing a threat to farmers’ livelihoods as well as to the nation’s food security. Indeed, across all of Asia, the IPCC found that India was “the most vulnerable nation in terms of crop production.”1

The government has earmarked large sums for adaptation efforts. Still, India urgently needs more adaptation finance. Interventions that strengthen livelihoods and boost incomes are particularly important for building climate resilience.

This report, a collaboration with support from HSBC India, identifies opportunities for philanthropies and impact investors to significantly enhance climate resilience in agrarian communities. In particular, it focuses on the needs of India’s more than 100 million “marginal” farmers – that is, smallholders and sharecroppers cultivating less than one hectare (2.47 acres) – and farm labourers.2

Recognising that vulnerable communities know best what they need to adapt but are often excluded from decisions that affect their lives, we surveyed nearly 800 farmers and nearly 150 labourers in four Indian states, and conducted in-depth interviews and field visits. We found that marginal farmers’ and farmworkers’ households are well aware of the changing climate’s impact on their farming habits. Yet they have fragile finances and social supports do not always reach them. For example, few farmers can document their land ownership, yet a land title is necessary to access some government schemes. Additionally, tailored support is also needed for particularly vulnerable social groups, such as women, Dalit, and Adivasi farmers.

The good news: philanthropies and impact investors with “patient capital” have opportunities to target investments in ways that can attract more finance from government sources or other private-sector investors. They can build on and collaborate with people and organisations that are already doing extraordinary work.

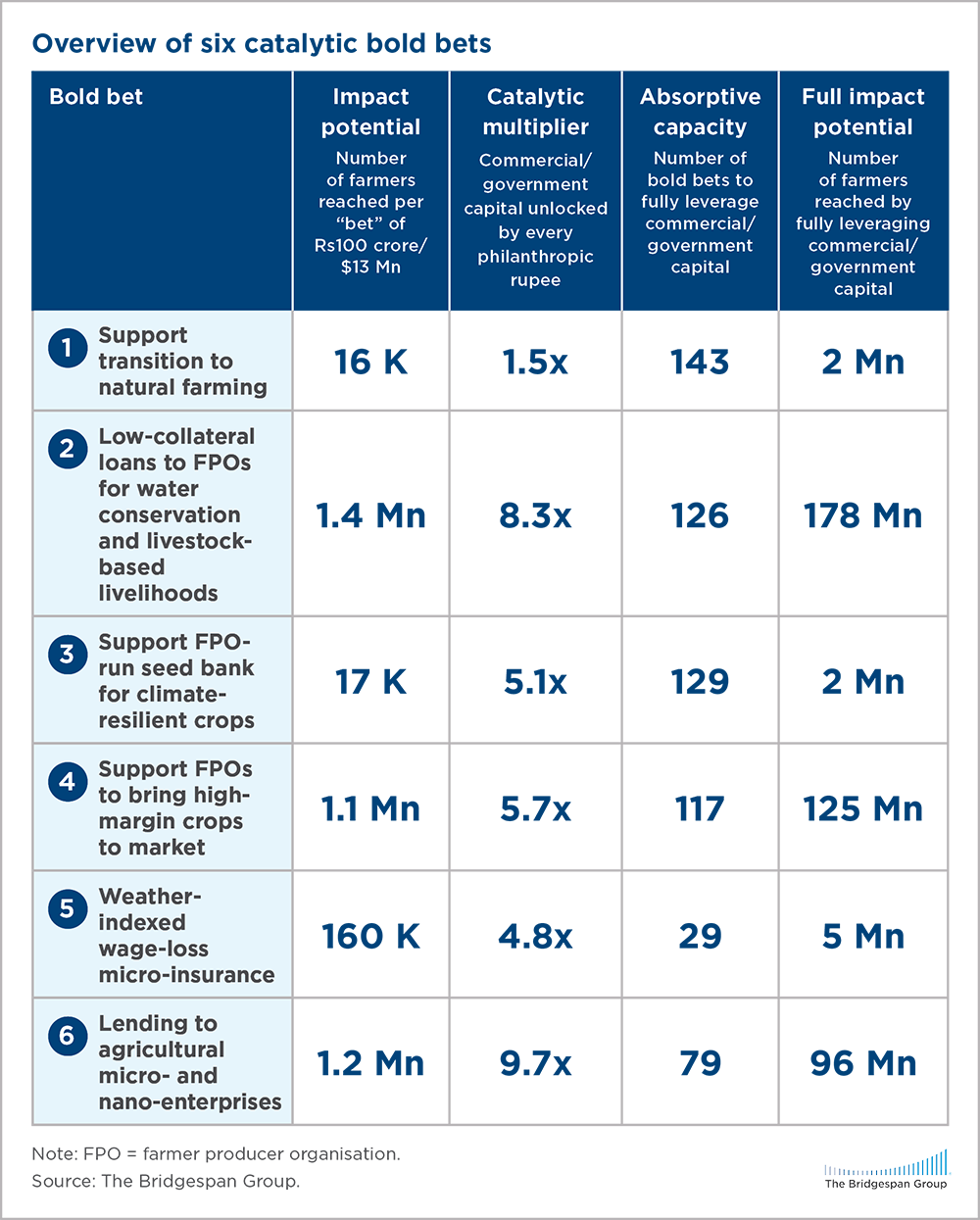

In particular, we analysed six prime opportunities – bold bets – to build resilience in India’s agrarian communities, with estimates of the potential impact of every Rs100 crore (about $13 million) invested.3

Many of the bold bets are already supported by philanthropy and other climate actors on a smaller scale. So we examined the evidence base and analysed the scale of capital available to fully realise the potential of each idea. We found opportunities for the bold bets to unlock existing government funding schemes and catalyse lending from commercial banks and microfinance institutions targeted to marginal farmers, farmer collectives, and farm labourers.

All told, if the six bold bets were fully capitalised, it could unlock 3.49 lakh crore rupees of adaptation finance – nearly $45 billion.

These estimates paint a picture of how much capital is currently mandated, allocated, or disbursed to support farmers and agricultural micro-, small-, and medium-size enterprises – and how much can be attracted by philanthropic and impact-first investments in bold bets. We hope our findings inform, inspire, and drive action for empowering vulnerable communities in adapting to climate change.