Most of our interactions across race are happening at work. We live in census tracts that look like us, our kids are in schools with classmates who look like them, and for the most part, our friendship groups tend to be predominately filled with people who share our identity. But the modern workplace is one of the few places in life where we’re all thrust together. Mission-driven organizations can either choose to seize that powerful opportunity to do things better, or we can replicate society’s problems.

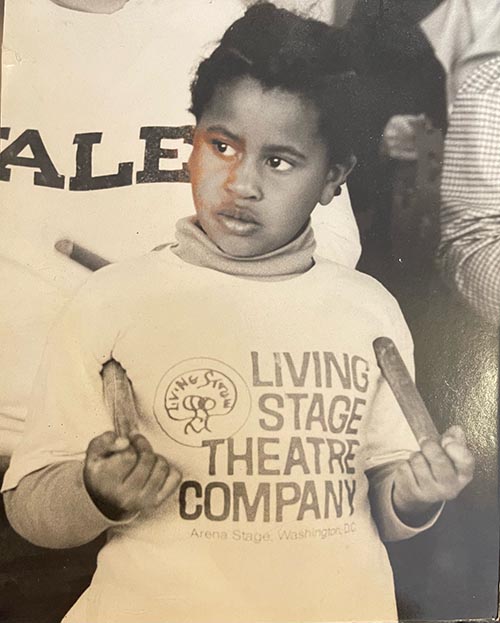

Raël’s belief in advancing equity was sparked by the afternoons she spent as a child at the Living Stage Theatre Company, a social-change theatre where her mother was an actress. (Photo: Raël Nelson James)I have seen the transformative power of proactively creating a community that grapples with race. When I was growing up in Washington, DC, my mom was a professional actress at the nonprofit Living Stage Theatre Company, the country’s preeminent theatre for social change. Founded in 1966 as intentionally multiracial, Living Stage believed in the power of the imagination to “make theatre accessible to oppressed people [and] to deal with racism permeating our soil.” Their interactive performances routinely tackled topics like economic inequity, race, police violence, and liberation, and were often accompanied by audience discussion of the issues. I spent my afternoons doing homework backstage or under the director’s table, soaking in Living Stage’s antiracist ideals. It meant that from early on I believed the advancement of equity to be a universal pursuit—something people of conscience from all racial backgrounds envisioned as our collective future.

Raël’s belief in advancing equity was sparked by the afternoons she spent as a child at the Living Stage Theatre Company, a social-change theatre where her mother was an actress. (Photo: Raël Nelson James)I have seen the transformative power of proactively creating a community that grapples with race. When I was growing up in Washington, DC, my mom was a professional actress at the nonprofit Living Stage Theatre Company, the country’s preeminent theatre for social change. Founded in 1966 as intentionally multiracial, Living Stage believed in the power of the imagination to “make theatre accessible to oppressed people [and] to deal with racism permeating our soil.” Their interactive performances routinely tackled topics like economic inequity, race, police violence, and liberation, and were often accompanied by audience discussion of the issues. I spent my afternoons doing homework backstage or under the director’s table, soaking in Living Stage’s antiracist ideals. It meant that from early on I believed the advancement of equity to be a universal pursuit—something people of conscience from all racial backgrounds envisioned as our collective future.

The Building Movement Project’s recent report, Blocking the Backlash, investigated the impact of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts on nonprofit organizations and staff. It found that the more DEI strategies an organization employs, the more likely the workplace experience will improve for all people—white and people of color. These strategies might include, for instance, diversifying the board, providing equity training at all levels of the organization, and clarifying that DEI is central to the organization’s purpose. Organizations with at least five DEI strategies saw retention rates for all staff start to increase. Building Movement Project’s report is just the latest addition to the huge body of research that demonstrates that DEI work is successful.

Despite all the evidence that DEI efforts improve the workplace for all, the everyday can still be an uphill battle for DEI professionals. What DEI professionals always need, especially in this moment, is for leadership to be the wind in our sails so we can push the work forward. I think the job for white allyship is whenever you’re able—particularly in conversations where there are only white people—push back against some of the spoken and unspoken harmful equity narratives in society that seep into the workplace and serve as a distraction. This can range from racial stereotypes and microaggressions to zero-sum thinking that assumes groups only get ahead at the expense of others. All of us must start seeing these mindsets—and not questioning them—as harmful. The work that can happen within the same identity spaces is critical because, while the message is important, so too is the messenger.

Building a More

Equitable Future

Visit our collection of tools and inspiration for philanthropists, nonprofits, and others working toward racial equity.

Unfortunately, lost in the current attacks on DEI work is the meaning of equity. To me, equity, at its most basic level, means that demographics are no longer a predictor of outcomes, and each person gets what they need to thrive. It is the linchpin for a society or organization that is fair and just for everyone. A few years ago, there was an article in The Atlantic by a historian who studies backlash. According to his research, the first time the term “backlash” really took hold was in 1963 when white resentment of the Civil Rights movement became palpable. While we often think of backlash as a fundamental tool of efforts to maintain the status quo, a finding of his research was that progressive movements have repeatedly been constrained by their own fear of setting off a backlash. To me, that is important because while organizations can’t control backlash to DEI, they can control allowing fear to preemptively stall the work’s ultimate goal of equity.

I feel personally called to DEI work because of the possibility that something we do in the workplace might also shape the conversations that my Bridgespan colleagues have around their dinner tables or might shape the way they engage with their communities. What would it mean for society outside of work if more organizations took DEI as a responsibility of their workplaces—what could that ripple effect be? I think those of us who believe in the promise of an inclusive and equitable society, where all people can thrive, recognize that on some fundamental level, it starts with one-to-one or small interactions and not with marches and grand declarations. It’s about seeing the humanity in people who are not like yourself. That then inspires how you interact with others and shapes your civic engagement as well. Because of the segregated silos of much of our lives, the workplace is now one of the most natural places for those interactions to happen.

My hope for the future is that younger generations become DEI natives in the same way that millennials are tech natives. Imagine the promise if we have generations that don’t know anything but diversity, equity, and inclusion being a way of life.